Mat Salleh Rebellion

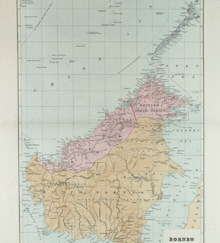

The Mat Salleh Rebellion was a series of major armed disturbances against the colonial British North Borneo Chartered Company administration in North Borneo, now the Malaysian state of Sabah. It was instigated by Datu Muhammad Salleh (also known as Mat Salleh), a local chief from the Lingkabo district and Sugut River. He led the rebellion between 1894 until his death in Tambunan in 1900.[1]:p.5[2]:p.41[3]:p.189–190 The resistance then continued on for another 5 years until 1905.[note 1][4]:p.54[5]:p.863

His revolts were widely supported by the local communities and affected a large geographical area from Sandakan, across Gaya Island, including the interior, especially Tambunan.[3]:p.190 His most notable uprising occurred at midnight on 9 July 1897, when he led his followers to successfully attack a major colonial settlement on Gaya Island.

Biography of Mat Salleh

Mat Salleh was born in Inanam.[3]:p.190[6] His father was Datu Balu, a traditional leader in Inanam and a member of the Suluk community.[6] His mother was of Bajau descent.[3]:p.189–190[7] He had three siblings: Ali, Badin and Bolong.[7] The family moved to Sugut, which unlike Inanam, was in the Company's concession but since the abandonment of its tobacco estates, it had reportedly been "left largely to its own devices",[8]:p.47 and enjoyed relative autonomy. There, Datu Bulu assumed a local leadership position along part of the Sugut River on the eastern coast of North Borneo.[5]

Later in his life, Mat Salleh married a Sulu princess named Dayang Bandang.[3]:p.190[6] She was related to the Sultan of Sulu's family and her village was at Penggalaban (maguindanaun dialogue), Paitan. He later inherited his father’s local leadership position as the village chieftain in the Lingkabau district and Sungei Sugut.[3]:p.190[6][7]

Mat Salleh was often physically described as slender and tall, with pockmarked features. He was also well known as a mysterious [note 2][5]:p.862[9]:p.64 and intelligent man, with a commanding personality and presence. He was well-respected and his great tactical skills were renowned among the local communities.[5]:p.862

Salleh's supporters

His mixed parentage and role as a traditional local leader which he had inherited from his father contributed to his significant Bajau and Suluk following. Also, his marriage to Dayang Bandang, who was related to the ruling family in Sulu helped him win more supporters.[3]:p.203–204

However, his wide support not only came from his family affiliations and connections. He was also able to garner supporters from Dusun communities spread over a sizeable geographical area in Sabah and had the Tagahas communities as allies, among others.[3]:p.204 He was skilled at connecting with and uniting other communities, making him a great personage among the multi-ethnic indigenous people.[5]:p.862 For example, some accounts claim that he used and married various symbols of authority and mysticism that the different communities could relate with to attest to his leadership position and military prowess.[note 3][5] :p.862

The large geographical areas where his support came from proved instrumental in ensuring the initial success of his revolt as these areas were available to provide power bases, supplies and construction of forts. This also implied that he and his army had ample mobility between forts and bases, which explains their successful repeated evasions of the Company’s troops. From 1895–1897, he had at his disposal at least six forts which were well-prepared with resources and manpower that he could mobilise at short notice.[3]:p.203–204

The forts that his followers built were impressively very well designed and constructed. They were reportedly to have been the:-

"most extraordinary place and without the guns [the company’s seven pounders] would have been absolutely impregnable. The buildings covered three sides of a square, the fourth side being closed by a stone wall. The whole square was 22 yards by 20 and the fact that over 200 shell burst inside will give some idea of its strength, the enemy still remaining in possession. The walls of the building were of stone, 8 feet thick with numerous large bamboos built into them for loopholes. The whole fort was surrounded with three bamboo fences… and the ground between was simply covered with ‘sudah’ (bamboo spikes)… on the inside of the square the loopholes were also very cunningly arranged to repel internal attack. There was neither exit nor entrance to the buildings and had an attacking force, no matter how strong, succeeded in reaching the middle of the square they would have been no nearer capturing the place than if they had stayed away, and they would have been shot down ... without the possibility of returning fire."[10]:p.416

The British North Borneo Chartered Company

Changes imposed

Before the arrival of the British, central authority in Sabah was weak. Part of it was governed by Brunei and part by the Sulu government.[11]:p.1 This gave local chiefs and traditional elites relative autonomy to practice influence and power to regulate trade in the area and serve the responsibility of protecting the local inhabitants from excessive exploitation by foreign traders.[3]:p.190

The British arrived during the late 19th century, and their administration (under the London-based British North Borneo Chartered Company) in North Borneo lasted sixty years, between 1881 and 1941.[5]:p.862[10][12] It aimed to transform North Borneo into a producer of various agricultural products, predominantly tobacco. Apart from the introduction of cash-crop farming, the Company also imposed new taxation laws and set up administrative centres. Some of the changes brought about by them were:

- Introduction of new taxes, including a levy on rice, the staple food of the population.[5]:p.863

- Poll-tax and passes for boats on local communities,[3]:p.190 including members of the local elites and traditional leaders.

- Mandatory licenses for local boat owners.[11]:p.2–3

- Passed a Village Ordinance, resulting in the Company not sanctioning the authority and traditional social position of a large number of traditional elites and local chiefs.[3]:p.190 This consequently alienated them and undermined their roles and social statuses.

- A customs station was built on Jambongan Island, staffed by a non-European clerk and policeman.[3]:p.190[8]:p.47

- A new police station was established on the Kinarom.[8]:p.47

In its attempt to revitalise the sagging economy, then managing director of the British North Borneo Company, William C. Cowie also launched two major projects:

- The construction of a cross-country rail between Brunei Bay and Cowie Harbour

- A telegraphic line from Labuan to Sandakan

New levies were imposed to finance these large-scale projects. Lack of manpower, however, caused the Company to rely on local chieftains as agents for revenue collection. Among those who cooperated with the Company, some abused their authority and overtaxed the natives, exacerbating dissatisfaction among local people already burdened by other new laws imposed by the Company. Mat Salleh viewed the Company’s new rules as an infringement of native rights,[3]:p.190 refused to acknowledge the Company's authority, and continued to collect taxes from traders traveling via the Sugut River as he had before the rules were imposed, without turning them over to the Company.[5]:p.47[8]:p.47[11]:p.4–7 Numerous other local chiefs shared Mat Salleh's strong opinions against the Company's new rules. Many of them later joined his cause.[5]:p.47[11]:p.4–7

Administrative centre relocated from Gaya Island to the mainland

The Company had set up its initial administrative centres on the west coast of Sabah in Papar and Tempassuk. In between these areas also stood the Gaya station,[note 4] set up in September 1882 as a collection station for jungle and local produce. This station also served as a "stopping place" for European officials plying between Kudat and Labuan.[2]:p.1 Gaya Island was initially thought of as a highly prospective settlement site and a possible port of call. It later however, did not flourish as expected; trade, collection of local produce and other economic activities did not prosper.[1] :p.1–5[2]:p.34 After the station in Gaya was raided and torched by Mat Salleh and his followers in July 1897,[note 5][2]:p.35 the British relocated to the mainland, in Gantian.

Mat Salleh uprisings, 1895–1905

At any rate, you will admit that your company cannot prevent us from dying for what we think are our rights.

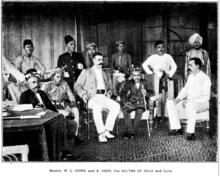

— Mat Salleh, to William C. Cowie, the managing director of the British North Borneo Company who had come from London on a special mission to arrange peace talks with him in 1898[3]:p.862

1894

Mat Salleh first came to the Company's attention when he was suspected of involvement in the murder and robbery of two Iban traders on the Sugut River in 1894.[8]:p.48 Captain Barnett and a few other colonial officials were sent to Mat Salleh's residence to investigate the matter.[note 6] Mat Salleh denied his and his followers’ involvement in it and resisted arrest.[5]:p.862[11]:p.8–9 This incident marked the first of many misunderstandings, creating a tense and hostile situation between both parties.

1895 (Sandakan incident)

In August 1895, in an attempt to have their grievances addressed through the colonial institution, Mat Salleh, his followers and traditional chiefs from Sugut went to Sandakan, then the seat of the government of North Borneo, to present a petition against the collection of poll-tax and the imposition of passes on boats by Government chiefs to then governor L. P. Beaufort and his representatives.[note 7][5]:p.862[11]:p.11 They were however, away on another expedition. Treasurer-in-general Alexander Cook, who was aware of their visit instead denied them an audience. After two days of waiting, Mat Salleh and his party left and headed back[2]:p.53

Following this, a complaint against Mat Salleh and his party was forwarded to the governor and other colonial officials by Cook. In response, on 29 August 1895, representatives from the Company arrived at Mat Salleh’s home in Jambongan to arrest him and four of his followers on the grounds of disturbing the peace at Sandakan and involvement with the murders of the two Ibans in 1894. Mat Salleh refused to comply and escaped. This led to his house and village being attacked, burned and looted. The company then announced him as a wanted man. A Straits $500 reward[note 8] was offered for his capture.[3]:p.193[5]:p.862[6][10]:p.407[11]:p.12–16

This incident triggered him to wage war against the British. He then consolidated his position at Lingkabau, approximately 50 miles up the Sugut river and with strong support from the native Dusun community there, built a strong fort. The British subsequently attacked it but failed to capture him. Instead, they destroyed it and apprehended about 60 Dusun natives.[3]:p.193

After this, he re-established himself in Labuk and built his headquarters at Limbawan. He had received support from the Labuk people as well. In September 1896, the British made another attack, surrounding Limbawan and cutting off possible escape routes. Again, they failed to apprehend him and also destroyed this fort.[3]:p.193–194 Following their escape, Mat Salleh and his followers built another fort at Padang at Ulu Sugut.[3]:p.194[10]:p.407–410

1897 (Gaya attack)

At midnight on 9 July 1897, Mat Salleh successfully led his followers to attack the Company’s settlement on Gaya Island.[3]:p.194[7] They raided and torched the Gaya compound before escaping with loot estimated to be worth Straits $100,000. They also took hostage F. S. Neubronner, the treasury clerk.[2]:p.5 The success of this attack increased his reputation as a local hero. This helped to further widen his reach, influence and support. After this attack, the Company proceeded to seek compensation from the Brunei Sultanate. The Managing Director, Cowie and the Governor, L. P. Beaufort, visited the Sultan of Brunei seeking compensation, claiming that some of the attackers were from regions under his jurisdiction. These areas were also claimed to have had been used as bases by Mat Salleh. The negotiations brought the Mengkabong, Manggatal and Api-Api districts (opposite of Gaya Island) under the Company's administration.[1]:p.5[2]:p.40

After the successful attack on Gaya Island, Mat Salleh and his followers moved on to a fort on the Soan on the Labuk, then Parachangan on the Sugut, then proceeded to attack and burn down the government residency at Ambong[5]:p.862[7] in November 1897.

Following this, he established his next fort at Ranau.[11]:p.21 On 13 December 1897, the Company attacked this Fort. They were defeated and lost about 10 men, including an Officer Jones, who had led the attack. On 9 January 1898, they attacked the fort for a second time with a bigger troop and captured it.[5]:p.862[7] However, by then, Mat Salleh and his men had already abandoned the fort and established a new one in the interior of Tambunan.[3]:p.194–195[7]

The Tambunan fort was stronger and more stable than his previous fort.[7] It was reported to have been

...very difficult to attack as the fort was built from stones, wood and bamboo which prevented the bullets from penetrating the walls of the fort. Each corner of the fort was guarded and there were many secret tunnels for them to seek assistance for firearms and food from outside the fort. These secret tunnels were also used for retreat when they were surrounded by the enemies[7]

This was also the last fort he used for defence in his struggle to rebel against the British.[7]

1898 (Palatan Peace Pact)

The tit-for-tat dual reached deadlock by early 1898. Cowie, managing director to the court of directors of the British North Borneo Chartered Company, personally travelled from London to arrange peace talks and a peace pact with Mat Salleh (the Palatan Peace Pact). Simultaneously, the Sultan of Sulu wrote a letter to Dayang Bandung, Mat Salleh’s wife, urging a peace settlement with Cowie.[3]:p.862[11]:p.27–29

The meeting occurred at Kampung Palatan in Ulu Menggatal on 19 April 1898. Mat Salleh was offered a pardon if resistance ceased. Cowie verbally promised amnesty and to allow Mat Salleh to settle in the Tambunan Valley, pledging noninterference from the government. Mat Salleh acceded[5]:p.863 and offered to accept it on two conditions:

- The release of his imprisoned men; and,

- That he be allowed to stay at Inanam.

Cowie refused these conditions, permitting Mat Salleh only to stay in Tambunan or parts of the interior excluding Sugut and Lambuk, his former strongholds. In addition, Cowie made an additional promise that if Mat Sallah kept his peace for twelve consecutive months and cooperated with the Company, Cowie would recommend Mat Sallah to the court of directors for an appointment as chief or headman of a district.[3]:p.195–196

On 20 April 1898, Cowie, governor L.P Beufort and two officers (P. Wise and A. Terms) met with Mat Salleh again and this time, he was allowed "to live in the interior and take charge of the Tambunan district".[3]:p.196 With this, a ceremony was held to mark Mat Salleh’s official possession of the Menggatal River on 22 April 1898. The next day, on 23 April 1898, the Company sent an official document to Mat Salleh to sign. The document stated that:

- Mat Salleh and his men were to be pardoned except those remaining in prison and those who had previously escaped;

- Mat Salleh could stay in Tambunan or elsewhere within the interior except the Sugut and Labuk rivers;

- That he was to report to the district officer on occasions he visited the coast[3]:p.196–197[note 9][5]:p.863

1899

Mat Salleh and his allies were at war with the Tiawan communities. The latter approached the Company with urgent appeals for its intervention. This led to the governor, Beaufort, on 15 January 1899, visiting the Tiawan villages and obtaining an oath of allegiance from them. This was also, apparently, a strategic move by the Company.[note 10][3]:p.198 to pursue its plans to establish an administrative centre in Tambunan.[3]:p.197–198[10]:p.431–432

Seeing this as a breach of faith to their earlier agreement, Mat Salleh prepared to resume resistance against the Company. In December 1899, R. M. Little, the resident of Labuan, was instructed to initiate negotiations. Mat Salleh refused negotiations and demanded their withdrawal from Tambunan. They refused. Almost immediately after this, Mat Salleh and his followers resumed waging sporadic attacks.[3]:p.198–201

1900–1905 (Mat Salleh's defeat)

The Company sent a force to retaliate. They reached Tambunan 31 December 1899 and fighting commenced the next day. On 10 January 1900, the Village of Laland was lost to the Company. Mat Salleh lost 60 men. On 15 January 1900, the Company proceeded to acquire Taga villages and the fort of one of Mat Salleh’s chief lieutenants; Mat Sator was burned by shell-fire. They then cut the water supply to Mat Salleh’s fort by diverting the Pengkalian river to the Sensuran.

On 27 January 1900, Mat Salleh’s own fort was seized and shelled continuously for the next four days. The seemingly impenetrable fort finally fell due to a massive onslaught by the Company, and with this, Mat Salleh's final defences were finally broken.[7]

On 31 January 1900, Mat Salleh was killed by shell-fire by mid-day.[note 11][3]:p.201–202[13]:p.194[11]:p.30[14]:p.35 A chance shot from a Maxim Gun had hit Mat Salleh in the left temple, killing him instantly.[4]:p.54[note 12][15] Also killed in the battle were about 1000 of Mat Salleh’s followers who fought from the neighbouring villages of Lotud Tondulu, Piasau, Kitutud, Kepayan and Sunsuron.[12][13]:p.194

It was, however, another five years before the remnants of Mat Salleh’s men surrendered, were killed or captured by the Company, marking the end of the rebellion in 1905.[note 1][3]:p.202–203[4]:p.54

Mat Salleh's memorial

The Mat Salleh memorial was opened in 1999 at the exact site where he was killed at Kampung Tibabar in Tambunan, as a tribute to remember Mat Salleh, who stood up and led a rebellion against the Company's rule.[7][12][13]:p.194 It was demolished in 2015.

The memorial, which resembled a fort, was surrounded by a garden. It housed Mat Salleh's photograph and some photos of his weapons and paraphernalia from the rebellion he led. A bronze plaque, set apart some metres from the building, still stands there and reads:[12]

This plaque marks the site of Mat Salleh's Fort which was captured by the North Borneo Armed Constabulary on the 1st February 1900. During this engagement, Mat Salleh, who for six years led a rebellion against the British Charted Company administration, met his death.

After the memorial was opened, The New Straits Times (9 Mar 2000) reported Sabah museum director and Tambunan local, Joseph Pounis Guntavid, as suggesting that the British had long bragged about putting down Mat Salleh’s rebellion against their rule and was quoted, ‘"but a search and study on Mat Salleh’s actions strongly indicated that he was not a rebel but a warrior who went against foreign rule, fighting for North Borneo ‘self-government’...Mat Salleh initiated patriotism that led the people to fight for self-rule until Sabah gained her independence through Malaysia on 16 September 1963".[13]:p.194

Mat Salleh, however, is not always seen as a hero. Many writers of this rebellion see Mat Salleh as a lone crusader and / or an opportunist solely interested in restoring his precolonial social position of power. To the British, he was a rebel and troublemaker, but to his supporters, he was and still is a warrior.[7][13]:p.194

Notes

- Sources conflict about the end date of the rebellion. Some state 1903, others 1905.

- Some of his supporters believed he possessed supernatural powers that made him invulnerable to physical harm and the inability to be hurt or killed by conventional weapons (typically known as Kebal in the Malay language). Even, invisibility so as not to be seen by his enemies. For many, his ability to repeatedly evade the Company's attacks served as proof of these claims.

- Some symbols that he used were enormous silk umbrellas (high society), insignia of royalty, and even inscriptions that were apparently believed to make him invincible.

- Gaya Island (along with other locations in the west coast of Sabah) was acquired by the British through an agreement with the Sultan of Brunei, Sultan Abdul Mumin Ebn Marhoum Maulana Abdul Wahab on 29 December 1877.

- Some British colonial sources claim that the abandonment of Gaya was not entirely caused by Mat Salleh. After the raid, the Company attempted to rebuild the township. However, it failed to economically flourish. Also, the company's railway project (above-mentioned under changes imposed after the arrival of the British North Borneo Chartered Company's arrival) that were started in 1896 had reached a stage where a suitable exit point was needed at the end of the line from Beaufort and Weston. As Gaya is an island, it had to be ruled out, and a new site had to be found on the mainland. With the acquisition of new territories from Brunei. There were also many new and more suitable sites to choose from.

- Some sources claim that Captain Barnett and his men were sent to confront, accuse and detain him. During this confrontation, Captain Barnett had attempted to forcefully apprehend Mat Salleh, but was outnumbered by his followers, ready to take up arms to protect him.

- There are two versions of this incident

- Mat Salleh came peacefully and apart from presenting his petition, meant to clear his name and settle the misunderstanding regarding his involvement in the Iban murders. Instead, he was treated with hostility by then present treasurer-in-general Alexander Cook, who then turned him away, causing much embarrassment to Mat Salleh.

- Mat Salleh arrived with an armed entourage of boats to present their petitions detailing their grievances towards the company. In the absence of Governor Leicester P. Beaufort, Cook, petrified by the show of force, requested through a representative that Mat Salleh and the others tender their petition in a formal manner and instructed them to disperse. There was a delay in relating this message and Cook’s request only reached Mat Salleh after he had waited for two days.

- Other accounts state that the reward was Straits $700.

- In some accounts, there was a discrepancy between the verbal and written agreement. Only when the written agreement was sent did Mat Salleh realise that he had been denied the pardon of his men who were escaped felons. Mat Salleh felt deceived and began to secretly strengthen his position in Tambunan.

- In the process of building a telegraph line, two new stations were established in the interior: one at Sapong in 1895 and another at Keningau in 1896, each under the European officer. The appointment of F W. Fraser at district offices at Keningau in 1898 signalled the extension of company rule to Tambunan.

- There are conflicting accounts for the date of Mat Salleh's death. Almost all sources state 31 January 1900, but there are a few that state 1 February 1900

- Some claim that Mat Salleh did not die during the Tambunan attack. In an interview conducted by a reporter from the Malaysian newspaper Bernama, Petrus Podtung Kuyog, 73, the grandson to one of Mat Salleh's followers strongly asserted that according to his grandmother, Giok's account; on 31 January 1900, Mat Salleh survived the attack and fled with his wife before going into hiding. His deputy was killed and was mistaken by the Company for Mat Salleh.

References

- Wong, Danny Tze Ken (2004). Historical Sabah: Community and Society. Kota Kinabalu: Natural History Publications (Borneo). ISBN 9838120901.

- Wong, Danny Tze Ken (December 2007). "From Gaya to Jesselton: A preliminary study on the establishment of a colonial township". Borneo Research Journal. 1: 31–42.

- Singh, Ranjit D. S. (2003). The making of Sabah 1865–1941: The dynamics of indigenous society (2nd ed.). Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press. ISBN 9831001648.

- Gill, Sarjit S.; 2007. "Sejarah Penglibatan orang Sikh dalam pasukan constabulari bersenjata Borneo Utara, 1882–1949 dan kesan terhadap identiti". Jebat (in Malay). 34: 49–70.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). "Mat Salleh Rebellion (1894–1905): Resisting foreign intrusion". Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor (3 volume set). ABC-CLIO: 862–863. ISBN 9781576077702.

- Zainal Abidin, bin Abdul Wahid; Khoo Kay Kim; Muhd Yusof bin Ibrahim; Singh, Ranjit D.S. (1994). Kurikulum Bersepadu Sekolah Menengah Sejarah Tingkatan 2 (in Malay). Kuala Lumpur: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka. ISBN 9836210091.

- "Mat Salleh". Sambutan kemerdekaan. Kementerian Penerangan Komunikasi & Kebudayaan. November 2011. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- Tarling, Nicholas (March 1985). "Mat Salleh and Krani Usman". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 16 (1): 46–68. doi:10.1017/s0022463400012765.

- Fernandez, Callistus (December 2001). "The legend by Sue Harris: A critique of the rundum rebellion and a counter argument on the rebellion". Kajian Malaysia. XIX (2): 61–78.

- Wookey, W. K. C. (December 1956). "The Mat Salleh Rebellion". Sabah Museum Journal. VII.

- Shuhada, ed. (1997). Mat Salleh: Pahlawan Sabah (in Malay). Kuala Lumpur: VC. ISBN 9830800385.

- Joseph Binkasan; Paskalis Alban Akim (2000). "A permanent tribute to one of Sabah's earliest freedom fighters". Reprinted from the New Straits Times, Thursday, 9 March 2000. Malaysian Museums. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- Thiessen, Tamara (2008). Kara Moses (ed.). Borneo: Sabah Brunei Sarawak. Guildford: Globe Pequot Press. ISBN 9781841623900.

- Luping, Herman J. (1994). Sabah's dilemma: The political history of Sabah. Kuala Lumpur: Magnus. ISBN 9839864009.

- Mansor, Nashir (31 January 2006). "Mat Salleh, The Man Who Antagonised The British" (Reprinted from newspaper article published by Bernama, 31 Jan (Year)). Bernama. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

External links

- Visit the Memorial (, , ).

- Read about an official biographical movie on Mat Salleh.

- Watch a fan video on Mat Salleh's life (part 1 / part 2).

- This entry mentions many parts of Sabah. Refer to a map of Sabah to follow Mat Salleh's movements throughout the rebellion.