Baku

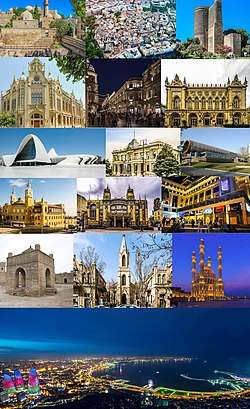

Baku (/bəˈkuː, bɑːˈkuː, ˈbɑːkuː, ˈbækuː/;[5] Azerbaijani: Bakı, IPA: [bɑˈcɯ]; Armenian: Բաքու) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located 28 metres (92 ft) below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world and also the largest city in the world located below sea level. Baku lies on the southern shore of the Absheron Peninsula, alongside the Bay of Baku. At the beginning of 2009, Baku's urban population was estimated at just over two million people.[6] Officially, about 25% of all inhabitants of the country live in Baku's metropolitan area. Baku is the sole metropolis in Azerbaijan.

Baku Bakı | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s): | |

Baku Location of Baku in Azerbaijan  Baku Baku (Azerbaijan)  Baku Baku (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 40°23′43″N 49°52′56″E | |

| Country | |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Eldar Azizov |

| Area | |

| • Capital city of Azerbaijan | 2,140 km2 (830 sq mi) |

| Elevation | −28 m (−92 ft) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Capital city of Azerbaijan | 2,293,700[2] |

| • Density | 1,057/km2 (2,740/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 3,125,000[3] |

| • Metro | 5,105,200 |

| Demonym(s) | Bakuvian[4] Azerbaijani: Bakılı |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

| Postal code | AZ1000 |

| Area code(s) | +994 12 |

| Vehicle registration | 10–90-99 AZ |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Walled City of Baku with the Shirvanshah's Palace and Maiden Tower |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv |

| Designated | 2000 (24th session) |

| Reference no. | 958 |

| Endangered | 2003–2009 |

| State Party | Azerbaijan |

| Region | Asia |

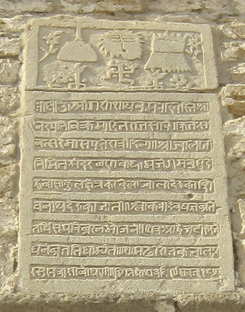

Baku is divided into twelve administrative raions and 48 townships. Among these are the townships on the islands of the Baku Archipelago, and the town of Oil Rocks built on stilts in the Caspian Sea, 60 kilometres (37 miles) away from Baku. The Inner City of Baku, along with the Shirvanshah's Palace and Maiden Tower, were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000. According to the Lonely Planet's ranking, Baku is also among the world's top ten destinations for urban nightlife.[7]

The city is the scientific, cultural, and industrial centre of Azerbaijan. Many sizeable Azerbaijani institutions have their headquarters there. The Baku International Sea Trade Port is capable of handling two million tonnes of general and dry bulk cargoes per year.[8] In recent years, Baku has become an important venue for international events. It hosted the 57th Eurovision Song Contest in 2012, the 2015 European Games, 4th Islamic Solidarity Games, the F1 Azerbaijan Grand Prix since 2016, hosted the final of the 2018–19 UEFA Europa League, and will be one of the host cities for UEFA Euro 2020.

The city is renowned for its harsh winds, which is reflected in its nickname, the "City of Winds".

Etymology

Baku is long attested under the Perso-Arabic name باکو (Bākū). Early Arabic sources also refer to the city as Bākuh and Bākuya,[9] all of which seem to come from a Persian name. The further etymology is unclear.

A popular etymology[10] in the 19th century considered it to be derived from Persian بادکوبه (Bâd-kube, meaning "wind-pounded city", a compound of bād, "wind", and kube, which is rooted in the verb کوبیدن kubidan, "to pound", thus referring to a place where wind would be strong and pounding,[11] as is the case of Baku, which is known to experience fierce winter snow storms and harsh winds). This popular name (Badkubə in modern Azerbaijani script) actually gained currency as a nickname for the city by the 19th century (e.g., it is used in Akinchi, volume 1, issue 1, p. 1), and is also reflected in the city's modern nickname as the "City of Winds" (Azerbaijani: Küləklər şəhəri). Another and even less probable folk etymology explains the name as deriving from Baghkuy, meaning "God's town". Baga (now بغ bagh) and kuy are the Old Persian words for "god" and "town" respectively; the name Baghkuy may be compared with Baghdād ("God-given") in which dād is the Old Persian word for "give".

During Soviet rule, the city was spelled in Cyrillic as "Бакы" in Azerbaijani (while the Russian spelling was and still is "Баку", Bakú). The modern Azerbaijani spelling, which has been using the Latin alphabet since 1991, is Bakı; the shift from the Perso-Arabic letter و (ū) to Cyrillic "ы" and, later, Latin "ı" may be compared to that in other Azerbaijani words (e.g. compare قاپو qāpū in old Perso-Arabic spelling with modern Azerbaijani qapı, "door") or in suffixes, as و was often used to transcribe the vowel harmony in Azerbaijani (which was also the practice in Ottoman Turkish). (See also Azerbaijani alphabet.)

History

Antiquity

Around 100,000 years ago, the territory of modern Baku and Absheron was savanna with rich flora and fauna. Traces of human settlement go back to the Stone Age. From the Bronze Age there have been rock carvings discovered near Bayil, and a bronze figure of a small fish discovered in the territory of the Old City. These have led some to suggest the existence of a Bronze Age settlement within the city's territory.[12] Near Nardaran, in a place called Umid Gaya, a prehistoric observatory was discovered, where on the rock the images of sun and various constellations are carved together with a primitive astronomic table.[13] Further archeological excavations revealed various prehistoric settlements, native temples, statues and other artifacts within the territory of the modern city and around it.

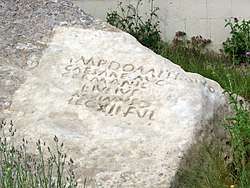

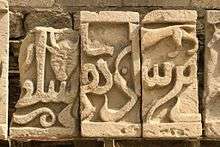

In the 1st century CE, the Romans organised two Caucasian campaigns and reached Baku. Near the city, in Gobustan, Roman inscriptions dating from 84–96 CE were discovered. This is one of the earliest written evidences for Baku.[14]

Rise of the Shirvanshahs and the Safavid era

Baku was the realm of the Shirvanshahs during the 8th century CE. The city frequently came under assault of the Khazars and (starting from the 10th century) the Rus. Shirvanshah Akhsitan I built a navy in Baku and successfully repelled another Rus assault in 1170. After a devastating earthquake struck Shamakhi, the capital of Shirvan, Shirvanshah's court moved to Baku in 1191.[15]

The Shirvan era greatly influenced Baku and the remainder of what is present-day Azerbaijan. Between the 12th and 14th centuries, massive fortifications were undertaken in Baku and the surrounding towns. The Maiden Tower, the Ramana Tower, the Nardaran Fortress, the Shagan Castle, the Mardakan Castle, the Round Castle and also the famous Sabayil Castle on the island of the Bay of Baku was built during this period. The city walls of Baku were also rebuilt and strengthened.

By the early 16th century Baku's wealth and strategic position attracted the focus of its larger neighbours; in the previous two centuries, it was under the rule of the in Iran-centred Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu. The fall of the Ak Koyunlu brought the city immediately into the sphere of the newly formed Iranian Safavid dynasty, led by king (shah) Ismail I (r. 1501–1524). Ismail I laid siege to Baku in 1501 and captured it; he allowed the Shirvanshahs to remain in power, under Safavid suzerainty. His successor, king Tahmasp I (r. 1524–1576), completely removed the Shirvanshahs from power, and made Baku a part of the Shirvan province. Baku remained as an integral part of his empire and the successive Iranian dynasties to come for the next centuries, until the irrevocable cession in the first half of the 19th century. The House of Shirvan, who ruled Baku since the 9th century, was extinguished in the course of the Safavid rule.

At this time the city was enclosed within the lines of strong walls, which were washed by the sea on one side and protected by a wide trench on land. The Ottomans briefly gained control over Baku as a result of the Ottoman-Safavid War of 1578–1590; by 1607, it was again put under Iranian control.[16] In 1604 Baku fortress was destroyed by Shah Abbas I (r. 1588-1629).

Baku is noted for being a focal point for traders from all across the world during the Early modern period, commerce was active and the area was prosperous. Notably, traders from the Indian subcontinent established themselves in the region. These Indian traders built the Ateshgah of Baku during 17th–18th centuries; the temple was used as a Hindu, Sikh, and Parsi place of worship.[17]

Downfall of the Safavids and the Khanate of Baku

In the wake of the demise of the Safavids, the Russians took advantage of the situation and invaded; the Safavids were forced to cede Baku to Russia for a few years.[18] By 1730, the situation had deteriorated for the Russians; the successes of Nader Shah (r. 1736–1747) forced them to make an agreement near Ganja on 10 March 1735, ceding the city and all other conquered territories in the Caucasus back to Iran.[19]

The eruption of instability following Nader Shah's death gave rise to the various Caucasian khanates. The semi-autonomous Persian-ruled[20][21] Baku Khanate was one of these. It was ruled by Mirza Muhammed Khan but soon became a dependency of the much stronger Quba Khanate. During this time, the population of Baku was small (approximately 5,000), and the economy was ruined as a result of constant warfare.

Russo-Persian Wars and Iran's forced ceding

From the late 18th century, Imperial Russia switched to a more aggressive geopolitical stance towards its two neighbours and rivals to the south, namely Iran and the Ottoman Empire. In the spring of 1796, by Catherine II’s order, General Valerian Zubov’s troops started a large campaign against Qajar Persia.[22] Zubov had sent 13,000 men to capture Baku, and it was overrun subsequently without any resistance. On 13 June 1796, a Russian flotilla entered Baku Bay, and a garrison of Russian troops was placed inside the city. Later, however, Pavel I ordered the cessation of the campaign and the withdrawal of Russian forces following his predecessor, Catherine the Great's death. In March 1797, the tsarist troops left Baku and the city became part of Qajar Iran again.

In 1813, following the Russo-Persian War of 1804–1813, Qajar Iran was forced to sign the Treaty of Gulistan with Russia, which provided for the irrevocable cession of Baku and most of Iran's territories in the North Caucasus and South Caucasus to Russia. During the next and final bout of hostilities between the two, the Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828, Baku was briefly recaptured by the Iranians. However, militarily superior, the Russians ended this war in a victory as well, and the resulting Treaty of Turkmenchay made its inclusion into the Russian Empire definite.[23] When Baku was occupied by the Russian troops during the war of 1804–13, nearly the entire population of some 8,000 people was ethnic Tat.[24]

Discovery of oil

The Russians built the first oil-distilling factory in Balaxani in 1837. Drilling for oil began in the mid-1800s, with the first oil well drilled in the Bibi-Heybat suburb of Baku in 1846.[25] It was mechanically drilled, though a number of hand-dug wells predate it. Large-scale oil exploration started in 1872 when Russian imperial authorities auctioned the parcels of oil-rich land around Baku to private investors. The pioneer of oil extracting from the bottom of the sea was Polish geologist Witold Zglenicki.[26] Soon after investors appeared in Baku, including the Nobel Brothers in 1873 and the Rothschilds in 1882. An industrial area of oil refineries, better known as Black Town, was established near Baku by the early 1880s.[27]

Professor A. V. Williams Jackson of Columbia University wrote in his work From Constantinople to the Home of Omar Khayyam (1911):

Baku is a city founded upon oil, for to its inexhaustible founts of naphtha it owes its very existence, its maintenance, its prosperity... At present Baku produces one-fifth of the oil that is used in the world, and the immense output in crude petroleum from this single city far surpasses that in any other district where oil is found. Verily, the words of the Scriptures find illustration here: 'the rock poured me out rivers of oil. Oil is in the air one breathes, in one's nostrils, in one's eyes, in the water of the morning bath (though not in the drinking water, for that is brought in bottles from distant mineral springs), in one's starched linen – everywhere. This is the impression one carries away from Baku, and it is certainly true in the environs.[28]

By the beginning of the 20th century, half of the oil sold in international markets was being extracted in Baku.[29] The oil boom contributed to the massive growth of Baku. Between 1856 and 1910 Baku's population grew at a faster rate than that of London, Paris or New York.

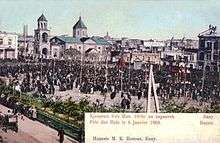

World War I

In 1917, after the October Revolution and amidst the turmoil of World War I and the breakup of the Russian Empire, Baku came under the control of the Baku Commune, which was led by veteran Bolshevik Stepan Shahumyan. Seeking to capitalize on the existing ethnic conflicts, by spring 1918, Bolsheviks inspired and condoned civil warfare in and around Baku. During the famous March Days, Bolsheviks and Dashnaks seeking to establish control over Baku streets, were faced with armed Azerbaijani groups. The Azerbaijanis suffered defeat by the united forces of Baku Soviet and were massacred by Dashnak teams in what was called March Days. An estimated 3,000–12,000 Azerbaijanis were killed in their own capital.[30][31] After the massacre, on 28 May 1918, the Azerbaijani faction of the Transcaucasian Sejm proclaimed the independence of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR) in Ganja, thereby becoming the first Muslim-majority democratic and secular republic.[32] The newly independent Azerbaijani republic, being unable to defend the independence of the country on their own, asked the Ottoman Empire for military support in accordance with clause 4 of the treaty between the two countries. Shortly after, Azerbaijani forces, with support of the Ottoman Army of Islam led by Nuru Pasha, started their advance onto Baku, eventually capturing the city from the loose coalition of Bolsheviks, Esers, Dashnaks, Mensheviks and British forces under the command of General Lionel Dunsterville on 15 September 1918.

After the Battle of Baku, the Azerbaijani irregular troops, with the tacit support of the Turkish command, conducted four days of pillaging and killing of 10,000 to 30,000[33] of the Armenian residents of Baku. This pogrom was known as the September Days. Shortly after this, Baku was proclaimed the new capital of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic.

Turkey lost the war by October 1918, then conducted the Armistice of Mudros with the British, which meant Baku was to be evacuated. Headed by General William Thomson, British troops of 5,000 soldiers, including parts of Dunsterforce, arrived in Baku on 17 November. Thomson declared himself military governor of Baku and implemented martial law on the capital until "the civil power would be strong enough to release the forces from the responsibility to maintain the public order". British forces left before the end of 1919.[34]

Soviet period

The independence of the Azerbaijani republic was significant but a short-lived chapter. On 28 April 1920, the 11th Red Army invaded Baku and reinstalled the Bolsheviks, making Baku the capital of the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic.

The city underwent many major changes. As a result, Baku played a great role in many branches of Soviet life. Baku was the major oil city of the Soviet Union. Since about 1921, the city was headed by Baku City Executive Committee, commonly known in Russian as Bakgorispolkom. Together with Baku Party Committee (known as the Baksovet), it developed the economic significance of the Caspian metropolis. From 1922 to 1930, Baku was the venue for one of the major Trade fairs of the Soviet Union, serving as a commercial bridgehead to Iran and the Middle East.[35]

World War II

Baku's growing importance as a major energy hub remained in sight of the major powers. During World War II and the Nazi German invasion of the southwestern Soviet Union, Baku had become of vital strategic importance. In fact, capturing the oil fields of Baku was one of the ultimate goals of Operation Edelweiss, carried out between May and November 1942. However, the German Army's closest approach to Baku was no closer than some 530 kilometres (329 miles) northwest of Baku in November 1942, falling far short of the city's capture before being driven back during the Soviet Operation Little Saturn in mid-December 1942.

Fall of the Soviet Union and later

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Baku embarked on a process of restructuring on a scale unseen in its history.[36] Thousands of buildings from the Soviet period were demolished to make way for a green belt on its shores; parks and gardens were built on the land reclaimed by filling up the beaches of the Baku Bay. Improvements were made in the general cleaning, maintenance, and garbage collection, and these services are now at Western European standards. The city is growing dynamically and developing at full speed on an east–west axis along the shores of the Caspian Sea. Sustainability has become a key factor in future urban development.[37]

Geography

Baku is situated on the western coast of Caspian Sea. In the vicinity of the city there are a number of mud volcanoes (Keyraki, Bogkh-bogkha, Lokbatan and others) and salt lakes (Boyukshor, Khodasan and so on).

Climate

Baku has a temperate semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSk) with hot and humid summers, cool and occasionally wet winters, and strong winds all year long. However, unlike many other cities with such climate features, Baku does not see extremely hot summers and substantial sunshine hours. This is largely because of its northerly latitude and the fact that it is located on a peninsula on the shore of the Caspian Sea. Baku, and the Absheron Peninsula on which it is situated, is the most arid part of Azerbaijan (precipitation here is around or less than 200 mm (8 in) a year). The majority of the light annual precipitation occurs in seasons other than summer, but none of these seasons is particularly wet. During Soviet times, Baku, with its long hours of sunshine and dry healthy climate, was a vacation destination where citizens could enjoy beaches or relax in now-dilapidated spa complexes overlooking the Caspian Sea. The city's past as a Soviet industrial centre left it one of the most polluted cities in the world, as of 2008.[38]

At the same time Baku is noted as a very windy city throughout the year, hence the city's nickname the "City of Winds", and gale-force winds, the cold northern wind khazri and the warm southern wind gilavar are typical here in all seasons. Indeed, the city is renowned for its fierce winter snow storms and harsh winds.[11] The speed of the khazri sometimes reaches 144 km/h (89 mph), which can cause damage to crops, trees and roof tiles.[39]

The daily mean temperature in July and August averages 26.4 °C (79.5 °F), and there is very little rainfall during that season. During summer the khazri sweeps through, bringing desired coolness. Winter is cool and occasionally wet, with the daily mean temperature in January and February averaging 4.3 °C (39.7 °F). During winter the khazri sweeps through, driven by polar air masses; temperatures on the coast frequently drop below freezing and make it feel bitterly cold. Winter snow storms are occasional; snow usually melts within a few days after each snowfall.

| Climate data for Baku | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

6.3 (43.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

29.7 (85.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.7 (49.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.4 (39.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

7.0 (44.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.5 (72.5) |

16.6 (61.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

7.3 (45.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.2 (39.6) |

9.4 (48.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

19.7 (67.5) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

19.4 (66.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

4.8 (40.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 21 (0.8) |

20 (0.8) |

21 (0.8) |

18 (0.7) |

18 (0.7) |

8 (0.3) |

2 (0.1) |

6 (0.2) |

15 (0.6) |

25 (1.0) |

30 (1.2) |

26 (1.0) |

210 (8.3) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 49 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1 cm) | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 89.9 | 89.0 | 124.0 | 195.0 | 257.3 | 294.0 | 313.1 | 282.1 | 222.0 | 145.7 | 93.0 | 102.3 | 2,207.4 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organisation (UN),[40] Hong Kong Observatory[41] for data of sunshine hours | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Meoweather (Snowy days)[42] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

Today, Baku is divided into 12 rayonlar (sub-rayons) (administrative districts) and 5 settlements of city type.[43][44]

Demographics

Until 1988, Baku had very large Russian, Armenian, and Jewish populations which contributed to cultural diversity and added in various ways (music, literature, architecture and progressive outlook) to Baku's history. With the onset of the Karabakh War and the pogrom against Armenians starting in January 1990, the city's large Armenian population was expelled.[45][46] Under Communism, the Soviets took over the majority of Jewish property in Baku and Kuba. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijani President Heydar Aliyev returned several synagogues and a Jewish college, nationalised by the Soviets, to the Jewish community. He encouraged the restoration of these buildings and is well liked by the Jews of Azerbaijan. Renovation has begun on seven of the original 11 synagogues, including the Gilah synagogue, built in 1896, and the large Kruei Synagogue.[47]

| Year | Azerbaijanis | % | Russians | % | Armenians | % | Jews | % | Others | % | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1851[48] | more than 5,000 | 405 | 5.5% | 7,431 | |||||||

| 1886[49] | 37,530 | 43.3 | 21,390 | 24.7 | 24,490 | 28.3 | 391 | 0.5 | 2,810 | 3.2 | 86,611 |

| 1897[50] | 40,341 | 36 | 37,399 | 33.4 | 19,099 | 17.1 | 3,369 | 3 | 11,696 | 10.5 | 111,904 |

| 1903[51] | 44,257 | 28.4 | 59,955 | 38.5 | 26,151 | 16.8 | n.a. | n.a. | 28,513 | 18.3 | 155,876 |

| 1913[51] | 45,962 | 21.4 | 76,288 | 35.5 | 41,680 | 19.4 | 9,690 | 4.5 | 41,052 | 19.1 | 214,672 |

| 1926[52] | 118,737 | 26.2 | 167,373 | 36.9 | 76,656 | 16.9 | 19,589 | 4.3 | 70,978 | 15.7 | 453,333 |

| 1939[53] | 215,482 | 27.4 | 343,064 | 43.6 | 118,650 | 15.1 | 31,050 | 3.9 | 79,377 | 10.1 | 787,623 |

| 1959[54] | 211,372 | 32.9 | 223,242 | 34.7 | 137,111 | 21.3 | 24,057 | 3.7 | 56,725 | 8.7 | 652,507 |

| 1970[55] | 586,052 | 46.3 | 351,090 | 27.7 | 207,464 | 16.4 | 29,716 | 2.3 | 88,193 | 6.9 | 1,262,515 |

| 1979[56] | 530,556 | 52.4 | 229,873 | 22.7 | 167,226 | 16.5 | 22,916 | 2.3 | 62,865 | 6.2 | 1,013,436 |

| 1999[57] | 1,574,252 | 88 | 119,371 | 6.7 | 378 | 0.02 | 5,164 | 0.3 | 89,689 | 5 | 1,788,854 |

| 2009[58] | 1,848,107 | 90.3 | 108,525 | 5.3 | 104 | 0.01 | 6,056 | 0.6 | 83,023 | 4.1 | 2,045,815 |

Ethnic groups

Today the vast majority of the population of Baku are ethnic Azerbaijanis (more than 90%). When Baku was occupied by the Russian troops during the war of 1804–13, nearly the entire population of some 8,000 people was ethnic Tat.[24] The intensive growth of the population started in the middle of the 19th century when Baku was a small town with a population of about 7,000 people. The population increased again from about 13,000 in the 1860s to 112,000 in 1897 and 215,000 in 1913, making Baku the largest city in the Caucasus region.[59]

Baku has been a cosmopolitan city at certain times during its history, meaning ethnic Azerbaijanis did not constitute the majority of population.[60] In 2003 Baku additionally had 153,400 internally displaced persons and 93,400 refugees.[61][62]

Religion

The urban landscape of Baku is shaped by many communities. The religion with the largest community of followers is Islam. The majority of the Muslims are Shia Muslims, and the Republic of Azerbaijan has the second highest Shia population percentage in the world after Iran.[64] The city's notable mosques include Juma Mosque, Bibi-Heybat Mosque, Muhammad Mosque and Taza Pir Mosque.

There are some other faiths practised among the different ethnic groups within the country. By article 48 of its Constitution, Azerbaijan is a secular state and ensures religious freedom. Religious minorities include Russian Orthodox Christians, Catholic Levantines, Georgian Orthodox Christians, Lutherans, Ashkenazi Jews and Sufi Muslims. Baky is the seat of the Catholic Apostolic Prefecture of Azerbaijan.

Zoroastrianism, although extinct in the city as well as in the rest of the country by the present time, had a long history in Azerbaijan and the Zoroastrian New Year (Nowruz) continues to be the main holiday in the city as well as in the rest of Azerbaijan.

Economy

Baku's largest industry is petroleum, and its petroleum exports make it a large contributor to Azerbaijan's balance of payments. The existence of petroleum has been known since the 8th century. In the 10th century, the Arabian traveler, Marudee, reported that both white and black oil were being extracted naturally from Baku.[65] By the 15th century, oil for lamps was obtained from hand-dug surface wells. Commercial exploitation began in 1872, and by the beginning of the 20th century the Baku oil fields were the largest in the world. Towards the end of the 20th century much of the onshore petroleum had been exhausted, and drilling had extended into the sea offshore. By the end of the 19th century skilled workers and specialists flocked to Baku. By 1900 the city had more than 3,000 oil wells, of which 2,000 were producing oil at industrial levels. Baku ranked as one of the largest centres for the production of oil industry equipment before World War II. The World War II Battle of Stalingrad was fought to determine who would have control of Baku oil fields. Fifty years before the battle, Baku produced half of the world's oil supply.[66]

The oil economy of Baku is undergoing a resurgence, with the development of the massive Azeri-Chirag-Guneshli field (Shallow water Gunashli by SOCAR, deeper areas by a consortium led by BP), development of the Shah Deniz gas field, the expansion of the Sangachal Terminal and the construction of the BTC Pipeline.

The Baku Stock Exchange is Azerbaijan's largest stock exchange, and largest in the Caucasian region by market capitalization. A relatively large number of transnational companies are headquartered in Baku. One of the more prominent institutions headquartered in Baku is the International Bank of Azerbaijan, which employs over 1,000 people. International banks with branches in Baku include HSBC, Société Générale and Credit Suisse.[67]

Tourism and shopping

Baku is one of the most important tourist destinations in the Caucasus, with hotels in the city earning 7 million euros in 2009.[68] Many sizable world hotel chains have a presence in the city. Baku has many popular tourist and entertainment spots, such as the downtown Fountains Square, the One and Thousand Nights Beach, Shikhov Beach and Oil Rocks. Baku's vicinities feature Yanar Dag, an ever-blazing spot of natural gas. On 2 September 2010, with the inauguration of National Flag Square, Baku became home to the world's tallest flagpole, according to the Guinness Book of Records.[69][70] However, on 24 May 2011 Baku lost this record by just 3 metres (9.8 feet) to the city of Dushanbe in Tajikistan.[71] As of October 2017, the Flag Pole is dismantled and the National Flag Square closed with fences.

Baku has several shopping malls; the most famous city centre malls are Port Baku, Park Bulvar, Ganjlik Mall, Metro Park, 28 MALL, Aygun city and AF MALL. The retail areas contain shops from chain stores up to high-end boutiques.

The city is listed 48th in the 2011 list of the most expensive cities in the world conducted by the Mercer Human Resource Consulting.[72] Its Nizami Street and also the Neftchilar Avenue are among the most expensive streets in the world.

Culture

The city has many amenities that offer a wide range of cultural activities, drawing both from a rich local dramatic portfolio and an international repertoire. In 2007 the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre designed by famous Iraqi-British architect, Zaha Hadid, was opened.[73] Baku also boasts many museums such as Baku Museum of Modern Art and Azerbaijan State Museum of History, most notably featuring historical artifacts and art. Many of the city's cultural sites were celebrated in 2009 when Baku was designated an Islamic Culture Capital.[74] Baku was chosen to host the Eurovision Dance Contest 2010. It has also become the first city hosting the first European Games in 2015.[75]

Theatres

- Azerbaijan State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre

- Azerbaijan State Academic Drama Theatre

- Azerbaijan State Russian Drama Theatre named after Samad Vurgun

- Baku Puppet Theatre (formally Azerbaijan State Puppet Theatre named after Abdulla Shaig)

- Azerbaijan State Theatre of Young Spectators

- Azerbaijan State Theatre of Musical Comedy

- Baku State Circus

- "Oda" Theatre

- Baku Marionette Theatre

- Baku Municipal Theatre

- Azerbaijan State Pantomime Theatre

- Mugham Azerbaijan National Music Theatre

- Azerbaijan State Theatre of Song named after Rashid Behbudov

- "UNS" Theatre

- "Yugh" Theatre

Among Baku's prestigious cultural venues are Azerbaijan State Philharmonic Hall, Azerbaijan State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre. The main movie theatre is Azerbaijan Cinema. Festivals include Baku International Film Festival, Baku International Jazz Festival, Novruz Festival, Gül Bayramı (Flower Festival) and the National Theater Festival.[76][77] International and local exhibitions are presented at the Baku Expo Centre.

As of 2012, the city along with Ganja and Lankaran participates in Earth Hour movement.[78][79]

Museums

Libraries

- ANAS Central Library of Science

- Presidential Library (former Library of the Armenian Philanthropic Society)

Architecture

Baku has wildly varying architecture, ranging from the Old City core to modern buildings and the spacious layout of Baku port. Many of the city's most impressive buildings were built during the early 20th century, when architectural elements of the European styles were combined in eclectic style.[80] Baku has an original and unique appearance, earning it a reputation as the 'Paris of the East'.[81] Baku joined UNESCO's Network of Creative Cities as a Design City on October 31, 2019 on the occasion of World Cities’ Day.[82]

Hamams

The Hamam tradition in Baku is interesting. There are a number of ancient hamams in Baku dating back to the 12th, 14th and 18th centuries. Hamams play a very important role in the architectural appearance of Baku.[83]

Teze Bey Hamam

Teze Bey is the most popular hamam (traditional bath) in Baku. It was built in 1886 in the centre of Baku and in 2003 it was fully restored and modernised. Along with its modern amenities, Teze Bey features a swimming pool and architectural details inspired by Oriental, Russian and Finnish baths.

Gum Hamam

Gum Hamam was discovered during archaeological excavations underneath the sand; hence the name: Gum hamam (sand bath). It was built sometime during the 12th–14th centuries.

Bairamali hamam

In ancient times Bairamali Hamam was called “Bey Hamam”. The original structure was built sometime during the 12th–14th centuries and was reconstructed in 1881.

Agha Mikayil Hamam

Agha Mikayil Hamam was constructed in the 18th century by Haji Agha Mikayil on Kichik Gala Street in the Old City (Icherisheher). It is still operating in its ancient setting. The Hamam is open to women on Mondays and Fridays and to men on the other days of the week.

Modern architecture

Late modern and postmodern architecture began to appear in the early 2000s. With economic development, old buildings such as Atlant House were razed to make way for new ones. Buildings with all-glass shells have appeared around the city, the most prominent examples being the Azerbaijan Tower, Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre, Flame Towers, Baku Crystal Hall, Baku White City, SOCAR Tower and DENIZ Mall. These projects also caught the attention of international media as notable programmes such as Discovery Channel's Extreme Engineering did pieces focusing in on changes to the city.[84]

The Old City of Baku, also known as the Walled City of Baku, refers to the ancient Baku settlement. Most of the walls and towers, strengthened after the Russian conquest in 1806, survived. This section is picturesque, with its maze of narrow alleys and ancient buildings: the cobbled streets past the Palace of the Shirvanshahs, two caravansaries, the baths and the Juma Mosque (which used to house the Azerbaijan National Carpet and Arts Museum but is now a mosque again). The old town core also has dozens of small mosques, often without any particular sign to distinguish them as such.

In 2003, UNESCO placed the Inner City on the List of World Heritage in Danger, citing damage from a November 2000 earthquake, poor conservation as well as "dubious" restoration efforts.[85] In 2009 the Inner City was removed from the List of World Heritage in Danger.[86]

Music and media

.jpg)

The music scene in Baku can be traced back to ancient times and villages of Baku, generally revered as the fountainhead of meykhana and mugham in the Azerbaijan.[87][88]

In recent years, the success of Azerbaijani performers such as AySel, Farid Mammadov, Sabina Babayeva, Safura and Elnur Hüseynov in the Eurovision Song Contest has significantly boosted the profile of Baku's music scene, prompting international attention. Following the victory of Azerbaijan's representative Eldar & Nigar at the Eurovision Song Contest 2011, Baku hosted the Eurovision Song Contest 2012.[89][90]

2005 was a landmark in the development of Azerbaijani jazz in the city. It has been home to legendary jazz musicians like Vagif Mustafazadeh, Aziza Mustafa Zadeh, Rafig Babayev and Rain Sultanov.[91][92] Among Baku's prominent annual fairs and festivals is Baku International Jazz Festival, which features some of the world's most identifiable jazz names.[93][94]

Baku also has a thriving International Centre of Mugham, which is located in Baku Boulevard, Gulustan Palace and Buta Palace, one of the principal performing arts centres and music venues in the city.[95]

The majority of Azerbaijan's media companies (including television, newspaper and radio, such as, Azad Azerbaijan TV, Ictimai TV, Lider TV and Region TV) are headquartered in Baku. The films The World Is Not Enough and The Diamond Arm are set in the city, while Amphibian Man includes several scenes filmed in Old City.

Out of the city's radio stations, Ictimai Radio, Radio Antenn, Burc FM, Avto FM, ASAN Radio and Lider FM Jazz are some of the more influential competitors with large national audiences.

Some of the most influential Baku newspapers include the daily Azadliq, Zaman (The Time), Bakinskiy Rabochiy (Baku Worker), Echo and the English-language Baku Today.

Baku is also featured in the video game Battlefield 4.[96]

Nightlife

Baku boasts a vibrant nightlife. Many clubs that are open until dawn can be found throughout the city. Clubs with an eastern flavour provide special treats from the cuisine of Azerbaijan along with local music. Western-style clubs target younger, more energetic crowds.[97] Most of the public houses and bars are located near Fountains Square and are usually open until the early hours of the morning.

Baku is home to restaurants catering to every cuisine and occasion. Restaurants range from luxurious and expensive to ordinary and affordable.[98]

In the Lonely Planet "1000 Ultimate Experiences", Baku placed 8th among the top 10 party cities in the world.[7][99]

Parks and gardens

Baku has large sections of greenery either preserved by the National Government or designated as green zones. The city, however, continues to lack a green belt development as economic activity pours into the capital, resulting in massive housing projects along the suburbs.[100]

Baku Boulevard is a pedestrian promenade that runs parallel to Baku's seafront. The boulevard contains an amusement park, yacht club, musical fountain, statues and monuments. The park is popular with dog-walkers and joggers, and is convenient for tourists. It is adjacent to the newly built International Centre of Mugham and the musical fountain.

Other prominent parks and gardens include Heydar Aliyev Park, Samad Vurgun Park, Narimanov Park, Alley of Honor and the Fountains Square. The Martyrs' Lane, formerly the Kirov Park, is dedicated to the memory of those who lost their lives during the Nagorno-Karabakh War and also to the 137 people killed on Black January.

Sports

Baku hosts a Formula One race on the Baku City Circuit. The first was the 2016 European Grand Prix, with the track going around the old city. The track measures 6.003 km (3.735 mi), and it has been on the Formula One calendar since its 2016 debut.

The city will also host three group games and one quarter-final of the UEFA Euro 2020 European Football Championship.[101]

Since 2002, Baku has hosted 36 major sporting events and selected to host the 2015 European Games.[102] Baku is also to host the fourth edition of the Islamic Solidarity Games in 2017.

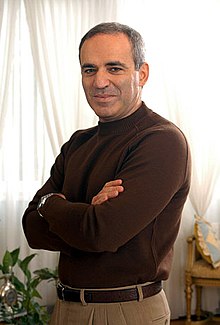

Baku is also one of world's leading chess centres, having produced famous grandmasters like Teimour Radjabov, Vugar Gashimov, Garry Kasparov, Shahriyar Mammadyarov and Rauf Mammadov, as well as the arbiter Faik Hasanov. The city also annually hosts the international tournaments such as Baku Chess Grand Prix, President's Cup, Baku Open and bidding to host 42nd Chess Olympiad in 2014.[103][104]

First class sporting facilities were built for the indoor games, including the Palace of Hand Games and Heydar Aliyev Sports and Exhibition Complex. It hosted many sporting events, including FIFA U-17 Women's World Cup, Rhythmic Gymnastics European Championships in 2007 and 2009, 2005 World Rhythmic Gymnastics Championships, 2007 FILA Wrestling World Championships and 2010 European Wrestling Championships, 2011 World Amateur Boxing Championships, 2009 Women's Challenge Cup and European Taekwondo Championships in 2007.[105][106] Since 2011 the city annually hosts WTA tennis event called Baku Cup.[107]

The Synergy Baku Cycling Project participates in the Tour d'Azerbaïdjan a 2.2 multi-stage bicycle race on the UCI Europe Tour.

Baku made a bid to host the 2016 Summer Olympics and 2020 Summer Olympics,[108] but failed to become a Candidate City both times.[109]

The largest sport hub in the city is Baku Olympic Stadium with 68,700 seating capacity whose construction was completed in 2015. UEFA Europa League Final 2019 was played at the Olympic Stadium in Baku on 29 May 2019 between English sides Chelsea and Arsenal.[110] The city's three main football clubs are Neftchi Baku, Inter Baku and Qarabağ FK of whom first has eight Premier League titles making Neftchi the most successful Azerbaijani football club. Baku also has several football clubs in the premier and regional leagues, including AZAL and Ravan in Premier League. The city's second largest stadium, Tofiq Bahramov Stadium hosts a number of domestic and international competitions and was the main sport centre of the city for a long period until the construction of Baku Olympic Stadium.

In the Azerbaijan Women's Volleyball Super League, Baku is represented by Rabita Baku, Azerrail Baku, Lokomotiv Baku and Azeryol Baku.

Transport

Throughout history the transport system of Baku used the now-defunct horsecars, trams and narrow gauge railways. As of 2011, 1,000 black cabs are ordered by Baku Taxi Company, and as part of a programme originally announced by the Transport Ministry of Azerbaijan, there is a plan to introduce London cabs into Baku.[111][112] The move was part of £16 million agreement between Manganese Bronze subsidiary LTI Limited and Baku Taxi Company.[113][114]

Local rail transport includes the Baku Funicular and the Baku Metro, a rapid-transit system notable for its art, murals, mosaics and ornate chandeliers. Baku Metro was opened in November 1967 and includes 3 lines and 25 stations at present; 170 million people used Baku Metro over the past five years.[115] In 2008, the Chief of Baku Metro, Taghi Ahmadov, announced plans to construct 41 new stations over the next 17 years. These will serve the new bus complex as well as the international airport.[116] In 2019, the Baku suburban railway opened.

BakuCard is a single Smart Card for payment on all types of city transport. The intercity buses and metro use this type of card-based fare-payment system.[117][118]

Baku Railway Station is the terminus for national and international rail links to the city. The Kars–Tbilisi–Baku railway, which directly connects Turkey, Georgia and Azerbaijan, began to be constructed in 2007 and opened in 2017.[119] The completed branch will connect Baku with Tbilisi in Georgia, and from there trains will continue to Akhalkalaki, and Kars in Turkey.[120]

Sea transport is vital for Baku, as the city is practically surrounded by the Caspian Sea to the east. Shipping services operate regularly from Baku across the Caspian Sea to Turkmenbashi (formerly Krasnovodsk) in Turkmenistan and to Bandar Anzali and Bandar Nowshar in Iran.[121] The commuter ferries, along with the high-speed catamaran Seabus (Deniz Avtobusu), also form the main connection between the city and the Absheron peninsula.[122]

Baku Port was founded in 1902 and since then has been the largest Caspian Sea port. It has six facilities: the main cargo terminal, the container terminal, the ferry terminal, the oil terminal, the passenger terminal and the port fleet terminal. The port's throughput capacity reaches 15 million tonness of liquid bulk and up to 10 million tons of dry cargoes.[123] Beginning in 2010, the Baku International Sea Trade Port is being reconstructed. The construction will take place in three stages and will be completed by 2016. The estimated costs are 400 Million US$.[124] From April to November Baku Port is accessible to ships loading cargoes for direct voyages from Western European and Mediterranean ports. The State Road M-1 and the European route E60 are the two main motorway connections between Europe and Azerbaijan. The motorway network around Baku is well developed and is constantly being extended. The Heydar Aliyev International Airport is the only commercial airport serving Baku. The new Baku Cargo Terminal was officially opened in March 2005. It was constructed to be a major cargo hub in the CIS countries and is actually now one of the biggest and most technically advanced in the region.[125] There are also several smaller military airbases near Baku, such as Baku Kala Air Base, intended for private aircraft, helicopters and charters.[126]

Education

Baku hosts many universities, junior colleges and vocational schools. Baku State University, the first established university in Azerbaijan was opened in 1919 by the government of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. In the early years of the Soviet era, Baku already had Azerbaijan State Oil Academy, Azerbaijan Medical University and Azerbaijan State Economic University. In the post-WWII period, a few more universities were established such as Azerbaijan Technical University, Azerbaijan University of Languages and the Azerbaijan Architecture and Construction University. After 1991 when Azerbaijan gained independence from the Soviet Union, the fall of communism led to the development of a number of private institutions, including Qafqaz University and Khazar University which are considered the most prestigious academic institutions. Apart from the private universities, the government established the Academy of Public Administration, the Azerbaijan Diplomatic Academy and various military academies. The largest universities according to the student population are Baku State University and Azerbaijan State Economic University. In addition, there are the Baku Music Academy and the Azerbaijan National Conservatoire in Baku established in the early 1920s. Publicly run kindergartens and elementary schools (years 1 through 11) are operated by local wards or municipal offices.

The Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, the main state research organisation in Azerbaijan is locating in Baku as well. Moreover, Baku has numerous libraries, many of which contain vast collections of historic documents from the Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman and Soviet periods, as well as from other civilisations of the past. The most important libraries in terms of historic document collections include the Nizami Museum of Azerbaijan Literature, the National Library of Azerbaijan, the Mirza Alakbar Central Library, the Samad Vurgun Library and Baku Presidential Library.

Health care

The city has many public and private hospitals, clinics and laboratories within its bounds and numerous medical research centres.[127] Many of these facilities have high technology equipment, which has contributed to the recent upsurge in "medical tourism" to Baku, particularly from post-Soviet countries such as Georgia and Moldova, whose governments send lower-income patients to the city for inexpensive high-tech medical treatments and operations.

Notable residents

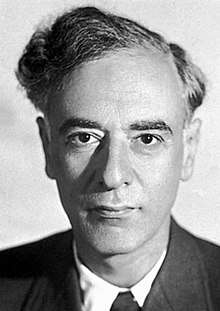

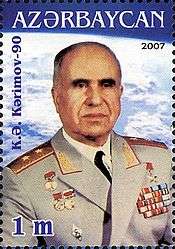

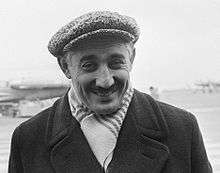

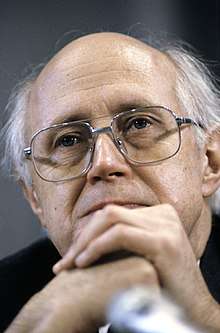

Because of its intermittent periods of great prosperity as well as being the largest city in the Caucasus and one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse in the Soviet Union, Baku prides itself on having produced a disproportionate number of notable figures in the sciences, arts and other fields. Some of the houses they resided in display commemorative plaques. Some of the many prestigious residents include: Academy Award winners Rustam Ibrahimbeyov and Vladimir Menshov, one of the founders and head of the Soviet space program Kerim Kerimov, Nobel Prize winner and physicist Lev Landau and famous musicians such as Gara Garayev, Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Muslim Magomayev, Vagif Mustafazadeh and Alim Qasimov. World-famous cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was born and raised in Baku, as was world-famous chess player Garry Kasparov.

Lotfi A. Zadeh, artificial intelligence researcher, founder of fuzzy mathematics, fuzzy set theory, and fuzzy logic

Lotfi A. Zadeh, artificial intelligence researcher, founder of fuzzy mathematics, fuzzy set theory, and fuzzy logic

Kerim Kerimov, one of the founders of the Soviet space program.

Kerim Kerimov, one of the founders of the Soviet space program. Garry Kasparov, chess grandmaster, former World Chess Champion.

Garry Kasparov, chess grandmaster, former World Chess Champion.- Mikayil Mushfig, Bakuvian poet and victim of the Stalinist purges.

Vagit Alekperov, President of the leading Russian oil company LUKOIL.

Vagit Alekperov, President of the leading Russian oil company LUKOIL. Muslim Magomayev, one of the most famous singers of the USSR.

Muslim Magomayev, one of the most famous singers of the USSR. Mstislav Rostropovich, Grammy Award–winning cellist.

Mstislav Rostropovich, Grammy Award–winning cellist. Yuli Gusman, film director and actor, founder and CEO of the Nika Award.

Yuli Gusman, film director and actor, founder and CEO of the Nika Award.

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Baku is twinned with:[128][129][in chronological order]

| Country | City | State / Province / Region / Governorate | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senegal | Dakar | Dakar Region | 1967[128][130][131][132] |

| Italy | Naples | Campania | 1972[133] |

| Iraq | Basra | Basra Governorate | 1972[128][130] |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | Sarajevo | Sarajevo Canton | 1975[128][130][131] |

| United States | Christiansted, United States Virgin Islands | Virgin Islands | 1976[128][134] |

| United States | Houston | Texas | 1976[128][134] |

| France | Bordeaux | Aquitaine | 1979[128][130][135] |

| Iran | Tabriz | East Azerbaijan Province | 1980[128][131] |

| Turkey | İzmir | İzmir Province | 1985[136] |

| Vietnam | Vũng Tàu | Bà Rịa–Vũng Tàu Province | 1985[130] |

| United States | Honolulu County | Hawaii | 1998[128][137] |

| Turkey | Sivas | Sivas Province | 2000[138] |

| Brazil | Rio de Janeiro | State of Rio de Janeiro | 2013[139] |

| Ukraine | Kiev | Kiev City | |

| Israel[140] | Haifa[140] |

Gallery

Baku Bay

Baku Bay Old Baku "Icheri Sheher"

Old Baku "Icheri Sheher" Baku Opera and Ballet Theatre

Baku Opera and Ballet Theatre Ismailiyya building

Ismailiyya building

- Icheri Sheher

Fountain and Azerbaijan State Philharmonic Hall

Fountain and Azerbaijan State Philharmonic Hall

Aerial view of Baku, May 2012

Aerial view of Baku, May 2012 View of Baku taken from the International Space Station

View of Baku taken from the International Space Station Evening Baku, Azerbaijan

Evening Baku, Azerbaijan Baku, Azerbaijan

Baku, Azerbaijan shipyard

shipyard

See also

References

- "Administrative, density and territorial units and land size by economic regions of Azerbaijan Republic for January 1. 2007". Archived from the original on 24 November 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- https://www.stat.gov.az/source/demoqraphy/?lang=en

- Demographia: World Urban Areas Archived 5 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine – Demographia, 2016

- Thomas de Waal (2010). The Caucasus: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-19-975043-6.

- "Baku". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- "Population by economic and administrative regions, urban settlements at the beginning of the 2009". Archived from the original on 14 November 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- "Travel Picks: Top 10 cities to party the night away". Reuters. 13 November 2009. Archived from the original on 23 November 2009. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- "Port of Baku". World Port Source. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- Dunlop, D.M.; Bennigsen, A.; Bosworth, C.E. (2007). Bosworth, C. Edmund (ed.). Historic Cities of the Islamic World (PDF). Leiden & Boston: Brill. p. 47. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "The origin and etymology", Bakucity.preslib.az

- "Culture & Religion on Podium: Politicizing Linguistics". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Город Баку... Archived 19 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 24 June 2006

- Ancient Observatory of Absheron. Gobustan, No 3 (1973)

- "Azerbaijan – Walled City of Baku with the Shirvanshah's Palace..." Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- "Ичери Шехер": быть или не быть Retrieved on 25 June 2006 Archived 20 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- Taleh Ziyadov (2012). Azerbaijan as a Regional Hub in Central Eurasia: Strategic Assessment of Euro-Asian Trade and Transportation. Taleh Ziyadov. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-9952-34-801-9.

- Shukiurov Kerim. "The Caucasus in the System of International Relations: The Turkmanchay Treaty was Signed 180 Years Ago". Cyberleninka. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). "Treaty of Ganja (1735)". In Mikaberidze, Alexander (ed.). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-59884-336-1.

- "Azerbaijan – history – geography". britannica.com. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- Russia and Iran, 1780-1828By Muriel Atkin, Page 16-20

- "Relations between Tehran and Moscow, 1797–2014". Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- Mojtahed-Zadeh, Pirouz (2007). Boundary Politics and International Boundaries of Iran: A Study of the Origin, Evolution, and Implications of the Boundaries of Modern Iran with Its 15 Neighbours in the Middle East by a Number of Renowned Experts in the Field. Universal. p. 372. ISBN 978-1-58112-933-5.

- James B. Minahan (2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 262. ISBN 978-1-61069-018-8.

- Smil, Vaclav (2017). Energy and Civilization: A History. Cambridge: The MIT Press. p. 246. ISBN 9780262035774.

- Witold Zglenicki

- Yergin, Daniel (1991). The Prize, The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 57–63. ISBN 9780671799328.

- Abraham Valentine Williams Jackson. "From Constantinople to the Home of Omar Khayyam". The Macmillan Company, 1911, p. 25. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- R.Hrair Dekmejian, Hovann H. Simonian (2003). Troubled Waters: The Geopolitics of the Caspian Region. I.B. Tauris. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-85771-755-9.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Smith, Michael (April 2001). "Anatomy of Rumor: Murder Scandal, the Musavat Party and Narrative of the Russian Revolution in Baku, 1917–1920". Journal of Contemporary History. 36 (2): 228. doi:10.1177/002200940103600202.

The results of the March events were immediate and total for the Musavat. Several hundreds of its members were killed in the fighting; up to 12,000 Muslim civilians perished; thousands of others fled Baku in a mass exodus

- Minahan, James B. Miniature Empires: A Historical Dictionary of the Newly Independent States. p. 22. ISBN 0-313-30610-9.

The tensions and fighting between the Azeris and the Armenians in the federation culminated in the massacre of some 12,000 Azeris in Baku by radical Armenians and Bolshevik troops in March 1918

- Tadeusz Swietochowski. Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-231-07068-3, ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3 and Reinhard Schulze. A Modern History of the Islamic World. I.B.Tauris, 2000. ISBN 1-86064-822-3, ISBN 978-1-86064-822-9.

- Andreopoulos, George (1997). Genocide: Conceptual and Historical Dimensions. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-1616-4, p. 236.

- Behbudov, Tahir. "British Police in Baku". Visions of Azerbaijan. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Etienne Forestier-Peyrat, ″Red Passage to Iran: Baku Trade Fair and the Unmaking of the Azerbaijani Borderland, 1922–1930 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine″, Ab Imperio, Vol 2013, Issue 4, pp. 79–112.

- "Money from oil changes the face of Azerbaijan". news.az. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- "Baku White City – Sustainability". www.bakuwhitecity.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Tiffany M. Luck (26 February 2008). "The World's Dirtiest Cities". Forbes. Archived from the original on 2 December 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- "Global ICT Conference: 25–28, November, 2004 : Baku, Azerbaijan". Global-ict.mincom.gov.az. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "World Weather Information Service". Archived from the original on 18 March 2010. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- "Climatological Information for Baku, Azerbaijan" Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine – Hong Kong Observatory

- "Baku, Azerbaijan". Meoweather. Archived from the original on 16 August 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- "Baku's History". Bakupages.com. 19 March 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Baku's History". Kishmish.az. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Azerbaijan: The status of Armenians, Russians, Jews and other minorities, report, 1993, INS Resource Informacion Center, p.10

- "Azerbaijan – The Soviet and post-Soviet periods". Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 April 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "JewishVirtualLibrary.org". JewishVirtualLibrary.org. 10 July 2006. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- (in Russian) Kavkazskii Kalendar na 1852 g., pp. 305–307

- (in Russian) Свод статистических данных о населении Закавказского края, извлечённых из посемейных списков 1886 года, г. Тифлис, 1893

- (in Russian) Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. – г. Баку Archived 19 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity Under Russian Rule, Audrey L. Altstadt, page 32, Hoover Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0-8179-9183-8

- (in Russian) Всесоюзная перепись населения 1926 года, т. 14, Закавказская СФСР, г. Москва, 1929

- Soviet 1939 census

- Soviet 1959 census

- Soviet 1970 census

- Soviet 1979 census

- "Ethnic composition of Azerbaijan 1999". Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "Ethnic composition of Azerbaijan 2009". Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "Country-data.com". Country-data.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Audrey Altstadt, Conflict, Cleavage and Change in Central Asia and the Caucasus, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p. 112, table 4.1, Ethnic composition of Baku, 1897, 1903,1913

- Баку (in Russian). Archived from the original on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- Герейханов, Гаджи Пирмурадович; Лукьянов, Алексей Григорьевич; Моренов, Игорь Сергеевич (2004). Угрозы национальной безопасности России на Северном Кавказе: этноконфессиональный аспект. Граница.

- Sharifov, Azad. "Legend of the Bibi-Heybat Mosque". Azerbaijan International Magazine. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- Juan Eduardo Campo,Encyclopedia of Islam, p.625

- "The History of Oil in Azerbaijan by Natig Aliyev". Azer.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- Aghazade, Emil (4 July 2005). "Азербайджан: сто лет надежд". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- Abdullayev, Rovshan. "Which foreign banks has Azerbaijan capital been trusted in?". Archived from the original on 18 May 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- "Hotels in Baku earned 6,8 million euros last year". Azerbaijan24.com. Archived from the original on 17 September 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Azerbaijani flag flies on world's tallest flagpole". news.az. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- "İşte dünyanın en yüksek bayrak direği" (in Turkish). ntvmsnbc.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2010. Retrieved 2 September 2010.

- "Guinness World Records". guinnessworldrecords.com. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- "Bakı dünyanın ən bahalı 48-ci şəhəridir, 13 July 2011, Azadlıq Radiosu. Retrieved 13 July 2011". Azadliq.org. 13 July 2011. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- "Heydər Əliyev Mərkəzi". heydaraliyevcenter.az. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- Azerbaijan Business Center. "Closing ceremony of Cultural Year "Baku- Islamic Culture Capital-2009" conducted in Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- "Baku 2015 European Games". Baku 2015. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- В Азербайджане отмечают праздник цветов. (in Russian) Archived 24 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Azerbaycan'da Gül Bayramı ve Aliyev'in doğum günü kutlanıyor Archived 24 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish)

- "Azerbaijan to join Earth Hour". www.news.az. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- "IDEA campaign to hold Earth Hour action". en.trend.az. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- "Baku's Architecture:A Fusion of East and West". Azer.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Архитектурное развитие города Archived 15 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- "UNESCO celebrates World Cities Day designating 66 new Creative Cities". UNESCO. 30 October 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Gadimova, Nazrin (8 January 2014). "Traditional hamams in all its glory in Baku". AzerNews.az. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre And Flame Towers". Discovery Communications. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Walled City of Baku with the Shirvanshah's Palace and Maiden Tower – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 2 March 2012. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Walled City of Baku with the Shirvanshah's Palace and Maiden Tower". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 22 September 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- "Meyxana", ya "bədihə" sözü aləmi bir-birinə qatıb Archived 7 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Azerbaijani)

- QARABAĞ MUĞAM MƏKTƏBİ Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Azerbaijani)

- Cadwalladr, Carole (15 May 2011). "Azerbaijan win Eurovision as Blue and Jedward finish mid-table". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- "Azerbaijan win Eurovision contest with Running Scared". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- "The Emergence of Jazz in Azerbaijan". Azer.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- MediaDesignTech. "History of Jazz in Azerbaijan". Jazz.az. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Baku International Jazz Festival has been opened in Azerbaijan". Azerbaijan24.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Baku International Jazz Festival Official Site". Festival.jazz.az. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "The Director-General hails the importance of living traditions at the Mugham Festival in Baku, Azerbaijan". Portal.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Battlefield 4 a sneaky screen from Baku". xboxplayers.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- "About Baku and Azerbaijan". Thelandmarkhotel.az. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- M. "Food and Restaurants in Azerbaijan and Baku". T-i.ifrance.com. Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- Beograd na vrhu liste gradova sa najboljim noćnim provodom (in Serbian) Archived 15 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Экология и охрана окружающей среды в Азербайджане Archived 15 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- "Euro 2020: England might have to play games at Hampden Park". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- "Azerbaijan is a country known for its love of sport and sportsmanship". www.baku2015.com. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "Azerbaijan bids to host Chess Olympiad". news.az. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- "Chess players from 11 countries to join "Baku Open 2010"". today.az. Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- Cev Cup: Final Four femminile a Baku (in Italian) Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Уралочка, Ямамай и ЦЗ. Добро пожаловать в бакинский ад! Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Russian)

- "2011 WTA Tournament Calendar". WTA. Archived from the original on 10 November 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- "Azerbaijan bids for 2020 Olympics in Baku – Olympics – ESPN". ESPN. 1 September 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "Olympic News – Official Source of Olympic News – Olympic.org". Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- UEFA.com. "Chelsea win the 2019 UEFA Europa League". UEFA.com. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- Meidment, Neil (3 March 2011). "Manganese Bronze seals biggest London taxi order". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- Jaglom, Ben. "Manganese takes black cab to Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 7 March 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "1,000 London taxis for Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "British firm wins £16m Azerbaijan order for its Chinese built taxis". Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- "Baku Metro Chief: "Baku-Sumgait metro line is not planned"". En.apa.az. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "41 new underground stations to be constructed in Azerbaijani capital in the next 17 years". Today.az. 10 October 2008. Archived from the original on 9 September 2009. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

- "How to pay your fare-Bakı Metropoliteni". www.metro.gov.az. Archived from the original on 9 May 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "BakuBus.az". www.bakubus.az. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- "Azerbaijani FM: Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railroad to be built in 2012". trend.az. Archived from the original on 18 October 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Railway Gazette International February 2009 p54 with map

- "Baku Sea Port expects for passenger trip Anzali-Baku". En.trend.az. 18 February 2010. Archived from the original on 19 February 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Ferry Service across Caspian sea". Azerbaijan24.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "Baku Sea Port". Bakuseaport.az. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- "Azerbaijan, Baku". m-hesse.com. Archived from the original on 15 January 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- "Heydar Aliyev International Airport (BAK/UBBB), Baku, Azerbaijan". Airport-technology.com. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Fevralın 14-ü Azərbaycan Hərbi Hava Qüvvələrinin (HHQ) yaranma günüdür (in Azerbaijani) Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Azerbaijan: Energy-Rich, Healthcare-Poor". Eurasianet.org. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- "Twin-cities of Azerbaijan". Azerbaijans.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2013.

- "The main directions of foreign relations of the executive authorities of Baku". Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- Musa Gasymly (2005). "АЗЕРБАЙДЖАН В МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫХ КУЛЬТУРНЫХ СВЯЗЯХ(1946–1990 гг.)" [Azerbaijan's cultural affairs (1946–1990)]. Tbilisi: Artanuchi. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "ВСЕ ОСТАЕТСЯ ЛЮДЯМ" [Everything remains for people]. 29 (19725). Vyshka. 25 July 2008. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "Monument in Dakar, on which "City Baku" was written in Russian and "City Dakar" in French". duesseldorfdakarcycling.wordpress.com. 2014.

- Flexibe Solutions (26 October 2007). "Embassy of Azerbaijan Republic in Italy". Azembassy.it. Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- Maud Beck (Winter 2006). "Sister Cities: Baku and Houston. Celebrating 30 Years as Sister Cities". Azerbaijan International: 68–71. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "Bordeaux-Atlas français de la coopération décentralisée et des autres actions extérieures". Délégation pour l’Action Extérieure des Collectivités Territoriales (Ministère des Affaires étrangères) (in French). Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- "İzmir Metropolitan Municipality". Izmir.bel.tr. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- "International Relations". Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-08.

- Uzaklar Yakinlaşti – Sivas Twin Towns Archived 27 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine(in Turkish)

- "Баку и Рио-де-Жанейро стали городами-побратимами – 1NEWS.AZ". archive.org. 7 December 2013. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013.

- "Azerbaijani US Ambassador: Israel Is a Pragmatic Partner and Good Friend, We Want it to Be Normal for Muslims and Jews to Be Allies". Algemeiner.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- "Executive Power of Baku City" (in Russian). Azerbaijan.az. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baku. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Baku (town). |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Baku. |

- UNESCO/ICOMOS (29 April 2003). "Joint UNESCO-ICOMOS Mission to the Walled City of Baku". UNESCO/url=http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001305/130571e.pdf |ICOMOS.

- Baku's profile at the Organization of World Heritage Cities website

- UNESCO World Heritage Site listing Walled City of Baku

- Photos of Baku

- Trip To Azerbaijan

_edited.jpg)

.svg.png)