Miniature (illuminated manuscript)

The word miniature, derived from the Latin verb miniare ("to colour with minium," a red lead[1]) indicates a small illustration used to decorate an ancient or medieval illuminated manuscript; the simple illustrations of the early codices having been miniated or delineated with that pigment. The generally small scale of such medieval pictures has led to etymological confusion with minuteness and to its application to small paintings, especially portrait miniatures,[2] which did however grow from the same tradition and at least initially used similar techniques.

Apart from the Western and Byzantine traditions, there is another group of Asian traditions, which is generally more illustrative in nature, and from origins in manuscript book decoration also developed into single-sheet small paintings to be kept in albums, which are also called miniatures, as the Western equivalents in watercolor and other mediums are not. These include Persian miniatures, and their Mughal, Ottoman and other Indian offshoots.

Italy and Byzantium, 3rd–6th centuries

The earliest extant miniatures are a series of colored drawings or miniatures cut from the Ambrosian Iliad, an illustrated manuscript of the Iliad from the 3rd century. They are similar in style and treatment with the pictorial art of the later Roman classical period. In these pictures there is a considerable variety in the quality of the drawing, but there are many notable instances of fine figure-drawing, quite classical in sentiment, showing that the earlier art still exercised its influence. Such indications, too, of landscape as are to be found are of the classical type, not conventional in the sense of medieval conventionalism, but still attempting to follow nature, even if in an imperfect fashion; just as in the Pompeian and other frescoes of the Roman age.[2]

Of even greater value from an artistic point of view are the miniatures of the Vatican manuscript of Virgil, known as the Vergilius Vaticanus, of the early 5th century. They are in a more perfect condition and on a larger scale than the Ambrosian fragments, and they therefore offer better opportunity for examining method and technique. The drawing is quite classical in style, and the idea is conveyed that the miniatures are direct copies from an older series. The colors are opaque: indeed, in all the miniatures of early manuscripts the employment of body color was universal. The method followed in placing the different scenes on the page is highly instructive of the practice followed, as we may presume, by the artists of the early centuries. It seems that the background of the scene was first painted in full, covering the whole surface of the page; then, over this background were painted the larger figures and objects; and over these again the smaller details in front of them were superimposed. (The painter's algorithm.) Again, for the purpose of securing something like perspective, an arrangement of horizontal zones was adopted, the upper ones containing figures on a smaller scale than those below.[2]

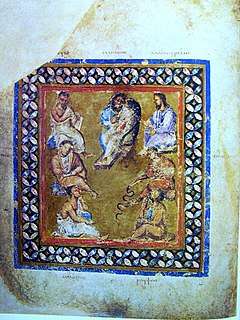

It was reserved for the Byzantine school to break away more decidedly from the natural presentment of things and to develop artistic conventions. Yet in the best early examples of this school the classical sentiment still lingers, as the relics of the miniatures of the Cotton Genesis, and the best of the miniatures of the Vienna Dioscurides testify; and in the miniatures of the later Byzantine manuscripts, which were copied from earlier examples, the reproduction of the models is faithful. But on comparing the miniatures of the Byzantine school generally with their classical predecessors, one has a sense of having passed from the open air into the cloister. Under the restraint of ecclesiastical domination Byzantine art became more and more stereotyped and conventional. The tendency grows to paint the flesh-tints in swarthy hues, to elongate and emaciate the limbs, and to stiffen the gait. Browns, blue-greys and neutral tints are in favor. Here we first find the technical treatment of flesh-painting which afterwards became the special practice of Italian miniaturists, namely the laying on of the actual flesh-tints over a ground of olive, green or other dark hue. Landscape, such as it was, soon became quite conventional, setting the example for that remarkable absence of the true representation of nature which is such a striking attribute of the miniatures of the Middle Ages.[2]

And yet, while the ascetic treatment of the miniatures obtained so strongly in Byzantine art, at the same time the Oriental sense of splendour shows itself in the brilliancy of much of the coloring and in the lavish employment of gold. In the miniatures of Byzantine manuscripts are first seen those backgrounds of bright gold which afterwards appear in such profusion in the productions of every western school of painting.[2]

The influence of Byzantine art on that of medieval Italy is obvious. The early mosaics in the churches of Italy, such as those at Ravenna and Venice, also afford examples of the dominating Byzantine influence. But the early Middle Ages provide but few landmarks to guide the student; and it is only when he emerges into the 12th century, with its frescoes and miniatures still bearing the impress of the Byzantine tradition, that he can be satisfied that the connection has always existed during the intervening centuries.[2]

Northwest Europe, 8th–12th centuries

In the native schools of illumination of Western Europe, decoration only was the leading motive. In the manuscripts of the Merovingian period, in the school which connected Frankland and northern Italy, and which is known as Lombardic or Franco-Lombardic, in the manuscripts of Spain, in the productions of the Insular art of the British Isles, figure-drawing was scarcely known, serving rather as a feature of decoration than as a representation of the human form.[2]

The Anglo-Saxon school, developed especially at Canterbury and Winchester, which probably derived its characteristic free-hand drawing from classical Roman models, scarcely influenced by the Byzantine element. The highest qualities of the miniatures of the 10th and 11th century of this school lie in fine outline drawing, which had a lasting influence on the English miniature of the later centuries. But the southern Anglo-Saxon school rather stands apart from the general line of development of the western medieval miniature.[2]

Under the Carolingian monarchs there developed a school of painting derived from classical models, chiefly of the Byzantine type. In this school, which owed its origin to the encouragement of Charlemagne, it is seen that the miniature appears in two forms. First, there is the truly conventional miniature following the Byzantine model, the subjects being generally the portraits of the Four Evangelists, or portraits of the emperors themselves: the figures formal; the pages brilliantly colored and gilded, generally set in architectural surroundings of a fixed type, and devoid of landscape in the real sense of the word. Accompanied as it was with profuse decoration in border and initial, it set the pattern for the later Continental schools of the West. On the other hand, there is also the miniature in which there is an attempt at illustration, as, for example, the depicting of scenes from the Bible. Here there is more freedom; and we trace the classical style which copies Roman, as distinguished from Byzantine, models.[2]

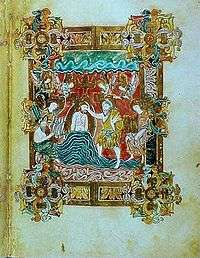

The influence which the Carolingian school exercised on the miniatures of the southern Anglo-Saxon artists shows itself in the extended use of body-color and in the more elaborate employment of gold in the decoration. Such a manuscript as the Benedictional of St. Æthelwold, bishop of Winchester, 963 to 984, with its series of miniatures drawn in the native style but painted in opaque pigments, exhibits the influence of the foreign art. But the actual drawing remained essentially national, marked by its own treatment of the human figure and by the disposition of the drapery with fluttering folds. The style was refined, tending to exaggeration and disproportion of the limbs. With the Norman Conquest this remarkable native school died.[2]

With the awakening of art in the 12th century the decoration of manuscripts received a powerful impulse. The artists of the time excelled in the border and the initial, but in the miniature also there was vigorous drawing, with bold sweeping lines and careful study of the draperies. The artists grew more practiced in figure-drawing, and while there was still the tendency to repeat the same subjects in the same conventional manner, individual effort produced in this century many miniatures of a very noble character.[2]

The Norman Conquest had brought England directly within the fold of Continental art; and now began that grouping of the French and the English and the Flemish schools, which, fostered by growing intercourse and moved by common impulses, resulted in the magnificent productions of the illuminators of north-western Europe from the latter part of the 12th century onwards.[2]

But of natural landscape there is nothing, unless rocks and trees of a stereotyped character can be so regarded. Hence the background of the miniature of the 12th and immediately succeeding centuries became the field for decoration to throw into stronger relief the figures in the scene. And thus arose the practice of filling in the entire space with a sheet of gold, often burnished: a brilliant method of ornament which we have already seen practiced in the Byzantine school. We have also to notice the conventional treatment of the sacred figures, which continue henceforward, from a sense of veneration, to be clad in the traditional robes of the early centuries, while the other figures of the scene wear the ordinary dress of the period.[2]

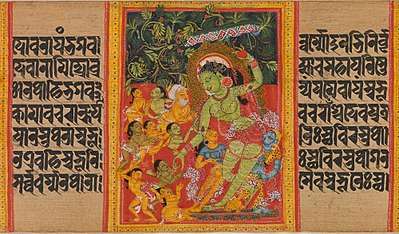

Pala Indian miniatures, 8th - 12th centuries

Under the patronage of Pala Dynasty miniature painting was introduced in India by painting on buddhist palm leaf manuscripts. One of the earliest surviving examples of Buddhist illustrated palm leaf manuscripts is Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā dated to 985 AD preserved in the University of Cambridge library.[3] The art of Pala illuminated manuscripts developed in Buddhist centers of Bihar and Bengal. The Pala miniature paintings not only inspired Nepalese and Tibetan miniature paintings but also inspired Hinduism and Jainism to develop their own miniature painting traditions in the later period.[4]

Northwest Europe, 13th–15th centuries

Entering the 13th century, we reach the period when the miniature may be said to justify the modern false etymology which has connected the title with minuteness. The broad, bold style of the 12th century gives place to the precise and minute. Books in general exchanged their form from the large folio to the octavo and smaller sizes. There was a greater demand for books; and vellum was limited in quantity and had to go further. Handwriting grew smaller and lost the roundness of the 12th century. Contractions and abbreviations in the texts largely increased in number. Everywhere there is an effort to save space. And so with the miniature. Figures were small, with delicate strokes in the features and with neat slim bodies and limbs. The backgrounds blaze with color and burnished gold; and delicate diaper patterns of alternate gold and color abound. Frequently, and especially in English manuscripts, the drawings are merely tinted or washed with transparent colors. In this century, too, the miniature invades the initial. Whereas in the earlier periods bold flowering scrolls are the fashion, now a little scene is introduced into the blank spaces of the letter.[2]

To compare the work of the three schools, the drawing of the English miniature, at its best, is perhaps the most graceful; the French is the neatest and the most accurate; the Flemish, including that of western Germany, is less refined and in harder and stronger lines. As to colors, the English artist affects rather lighter tints than those of the other schools: a partiality is to be observed for light green, for grey-blue, and for lake. The French artist loved deeper shades, especially ultramarine. The Fleming and the German painted, as a rule, in less pure colors and inclined to heaviness. A noticeable feature in French manuscripts is the red or copper-hued gold used in their illuminations, in strong contrast to the paler metal of England and the Low Countries.[2]

It is remarkable how the art of the miniature throughout the 13th century maintains its high quality both in drawing and color without any very striking change. Throughout the century the Bible and the Psalter were in favor; and naturally the same subjects and the same scenes ran through the period and were repeated by artist after artist; and the very character of those sacred books would tend to restrain innovation. But towards the close of the period such secular works as the romances were growing in popularity, and afforded a wider field for the invention of the illustrating artist. Therefore, with the opening of the 14th century a palpable change of style supervenes. We pass to more flowing lines; not to the bold sweeping strokes and curves of the 12th century, but to a graceful, delicate, yielding style which produced the beautiful swaying figures of the period. In fact the miniature now begins to free itself from the role of an integral member of the decorative scheme of illumination and to develop into the picture, depending on its own artistic merit for the position it is to hold in the future. This is shown by the more prominent place that the miniature now assumes, and by its growing independence of the decorative border and initial.[2]

But, at the same time, while the miniature of the 14th century thus strives to dissociate itself from the rest of the illuminated details of the manuscript, within itself it flourishes in decoration. Besides the greater elasticity of the figuredrawing, there is a parallel development in the designs of the backgrounds. The diapers become more elaborate and more brilliant; the beauty of the burnished gold is enhanced by the stippled patterns which are frequently worked upon it; the gothic canopies and other architectural features which it became the practice to introduce naturally followed the development of the architecture of the period. In a word, the great expansion of artistic sentiment in decoration of the best type, which is so prominent in the higher work of the 14th century, is equally conspicuous in the illuminated miniature.[2]

In the early part of the century, English drawing is very graceful, the figures bending with a waving movement which, if they were not so simple, would be an affectation. Both in the outline specimens, washed with transparent color, and in the fully. painted examples, the best English work of this time is unsurpassed. French art still maintains its neat precision, the colors more vivid than those of England and the faces delicately indicated without much modelling. The productions of the Low Countries, still keeping to the heavier style of drawing, appear coarse beside the works of the other schools. Nor does German miniature art of this period hold a high position, being generally mechanical and of a rustic character. As time advances the French miniature almost monopolizes the field, excelling in brilliancy of coloring, but losing much of its purity of drawing although the general standard still remains high. The English school gradually retrogrades and, owing no doubt to political causes and to the wars with France, appears to have produced no work of much value. It is only towards the end of the 14th century that there is a revival.[2]

This revival has been attributed to a connection with the flourishing school of Prague, a school which in the scheme of coloring suggests a southern influence following on the marriage of Richard II with Anne of Bohemia in 1382. The new style of English miniature painting is distinguished by richness of color, and by the careful modelling of the faces, which compares favorably with the slighter treatment by the contemporary French artists. Similar attention to the features also marks the northern Flemish or Dutch school at this period and in the early 15th century; and it may therefore be regarded as an attribute of Germanic art as distinguished from the French style.[2]

The promise of the new development in English miniature painting, however, was not to be fulfilled. In the first quarter of the 15th century, examples of great merit were produced, but at a standstill in drawing and fettered by medieval convention. The native art practically came to a close about the middle of the century, just when the better appreciation of nature was breaking down the old conventional representation of landscape in European art, and was transforming the miniature into the modern picture. Whatever miniature painting was to be produced in England after that time was to be the work of foreign artists or of artists imitating a foreign style. The condition of the country during the Wars of the Roses sufficiently accounts for the abandonment of art. Thus the history of the miniature in the 15th century must be sought in the manuscripts of the Continental schools.[2]

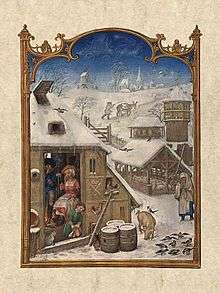

First we have to consider northern France and the Low Countries. As it passes out of the 14th and enters the 15th century, the miniature of both schools begins to exhibit greater freedom in composition; and there is a further tendency to aim rather at general effect by the coloring than neatness in drawing. This was encouraged by the wider field opened to the miniaturist. Books of all kinds were illustrated, and sacred books, Bibles and Psalters and liturgical books, were no longer the chief, if not the only, manuscripts which were illuminated. And yet there was one class of manuscript which came into the greatest prominence and which was at the same time liturgical. This was the Horae, or Book of Hours, devotional books for individual use, which were multiplied in vast numbers and contained some of the finest work of the miniaturists. The decoration of these little volumes escaped in great measure from the conventional restraints which their religious character might have imposed. Furthermore, the demand for illuminated manuscripts had by this time established a regular trade; and their production was not confined, as formerly, to the cloister.[2] Notable secular illuminated manuscript artists include Master Honoré of the Parisian school.

Early in the century the old conventional treatment of landscape still held its own; nor did the diapered and gilded background pass out of use. Indeed, in some of the finest French specimens of the time the diapered patterns are more brilliant than ever. But natural scenery in the second quarter of the century asserts itself more decidedly, although with faults in perspective. It was not until another generation had arisen that there was a true appreciation of the horizon and of atmospheric effect.[2]

The miniatures of the French and Flemish schools run fairly parallel for a time, but after the middle of the century national characteristics become more marked and divergent. The French miniature began to deteriorate, though some very fine examples were produced by the more gifted artists of the school. The figure-drawing was more careless, and the painting tended to hardness without depth, which the artist endeavoured to relieve by an excess of gilt shading.[2]

The Flemish school in the latter part of the 15th century attained to its highest excellence. The Flemish miniature affected extreme softness and depth of color; also an ever-increasing carefulness in the treatment of details, of the draperies, of the expression of the features: the Flemish type of the Virgin's face, for example, with its full, high forehead, can never be mistaken. In the best Flemish miniatures of the period the artist succeeds in presenting a wonderful softness and glow of color; nor did the high standard cease with the 15th century, for many excellent specimens still remain to attest the favor in which it was held for a few decades longer.[2]

In the foregoing remarks what has been said in regard to the careful treatment of details applies still more to the miniatures executed in grisaille, in which the absence of color invited an even stronger accentuation of that treatment. This is perhaps most observable in the grisaille miniatures of northern Flanders, which often suggest, particularly in the strong angular lines of the draperies, a connection with the art of the wood engraver.[2]

Italy, 13th–15th centuries

.jpg)

The Flemish miniature did not, however, hold the favor of western Europe without a rival. That rival had arisen in the south, and had come to perfection concurrently with the miniature of the Low Countries in the 15th century. This was the Italian miniature, which passed through the same stages as the miniatures of England and France and the Low Countries. Intercommunication between the countries of Europe was too well established for the case to be otherwise. In Italian manuscripts of the normal type the influence of Byzantine art is very manifest during the 13th and 14th centuries. The old system of painting the flesh tints upon olive green or some similar pigment, which is left exposed on the lines of the features, thus obtaining a swarthy complexion, continued to be practiced in a more or less modified form into the 15th century. As a rule, the pigments used are more opaque than those employed in the northern schools; and the artist trusted more to color alone to obtain the desired effect than to the mixture of color and gold which gave such brilliant results in the diapered patterns of France. The vivid scarlet of the Italian miniaturists is peculiarly their own. The figure-drawing is less realistic than the contemporary art of English and French manuscripts, the human form being often thick-set. In general, the Italian miniature, before its great expansion in the 14th century, is far behind the miniatures of the north. But with the 15th century, under the influence of the Renaissance, it advanced into the front rank and rivalled the best work of the Flemish school. The use of thicker pigments enabled the miniaturist to obtain the hard and polished surface so characteristic of his work, and to maintain sharpness of outline, without losing the depth and richness of color which compare with the same qualities in the Flemish school.[2]

The Italian style was followed in the manuscripts of Provence in the 14th and 15th centuries. It had its effect, too, on the school of northern France, by which it was also influenced in turn. In the manuscripts of southern Germany it is also in evidence. But the principles which have been reviewed as guiding the development of the miniature in the more important schools apply equally to all. Like the miniature of the Flemish school, the Italian miniature was still worked to some extent with success, under special patronage, even in the 16th century; but with the rapid displacement of the manuscript by the printed book the miniaturist's occupation was brought to a close.[2]

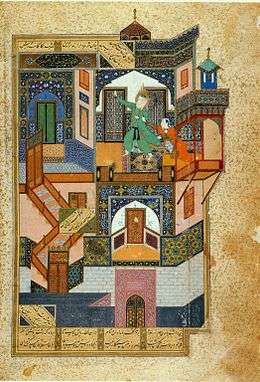

Persian

Persian art has a long tradition of the use of miniatures.

Reza Abbasi (1565–1635), considered one of the most renowned Persian painters of all time, specialized in the Persian miniature, with a preference for naturalistic subjects. Today his surviving works can be found in many of the major museums of the Western world, such as the Smithsonian, the Louvre and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mughal miniatures

Mughal painting developed during the period of the Mughal Empire (16th - 18th centuries) and was generally confined to miniatures either as book illustrations or as single works to be kept in albums. It emerged from the Persian miniature painting tradition introduced to India by Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad in the mid 16th century. It soon moved away from its Safavid origins; with the influence of Hindu artists, colors became brighter and compositions more naturalistic. The subject matter was predominantly secular, mainly consisting of illustrations to works of literature or history, portraits of court members and studies of nature. At its height the Mughal painting style represented an elegant marriage of Persian, European, and Hindi art.[5]

Forgeries

Medieval miniatures have been forged to deceive collectors by various persons, most notably including the Spanish Forger.

References

- Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1855). "On False Etymologies". Transactions of the Philological Society (6): 70.

-

- "Sanskrit Manuscripts : Prajñāpāramitāstotra, Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 2018-06-02.

- Art, Los Angeles County Museum of; Pal, Pratapaditya; Richardson, Hugh (1983). Art of Tibet: A Catalogue of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art Collection. University of California Press. ISBN 9780875871127.

- Art, Author: Department of Islamic. "The Art of the Mughals before 1600 | Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- Otto Pächt, Book Illumination in the Middle Ages (trans fr German), 1986, Harvey Miller Publishers, London, ISBN 0-19-921060-8

- Walther, Ingo F. and Wolf, Norbert, Masterpieces of Illumination (Codices Illustres); pp 350–3; 2005, Taschen, Köln; ISBN 3-8228-4750-X

- Jonathan Alexander; Medieval Illuminators and their Methods of Work; p. 9, Yale UP, 1992, ISBN 0-300-05689-3

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Papadaki-Oekland Stella,Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts of the Book of Job, ISBN 2-503-53232-2.

Further reading

- Kren, T. & McKendrick, Scot (eds), Illuminating the Renaissance – The Triumph of Flemish Manuscript Painting in Europe, Getty Museum/Royal Academy of Arts, 2003, ISBN 1-903973-28-7

- McKendrick, Scot; Lowden, John; Doyle, Kathleen, (eds), Royal Manuscripts, The Genius of Illumination, 2011, British Library, ISBN 9780712358156

- T. Voronova and A Sterligov, Western European Illuminated Manuscripts (in the St Petersberg Public Library), 2003, Sirocco, London

- Weitzmann, Kurt. Late Antique and Early Christian Book Illumination. Chatto & Windus, London (New York: George Braziller) 1977.

- Nordenfalk, Carl. Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Painting: Book illumination in the British Isles 600–800. Chatto & Windus, London (New York: George Braziller), 1977.

- Brown, Michelle P., Manuscripts from the Anglo-Saxon Age, 2007, British Library, ISBN 9780712306805

- Williams, John, Early Spanish Manuscript Illumination Chatto & Windus, London (New York, George Braziller), 1977.

- Cahn, Walter, Romanesque Bible Illumination, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1982, ISBN 0801414466

Persian

- Canby, Sheila R., Persian Painting, 1993, British Museum Press, ISBN 9780714114590

- Titley, Norah M., Persian Miniature Painting, and its Influence on the Art of Turkey and India, 1983, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0292764847

- Welch, Stuart Cary. Royal Persian Manuscripts, Thames & Hudson, 1976, ISBN 0500270740

19th-century revival

- Sandra Hindman, Michael Camille, Nina Rowe & Rowan Watson, Manuscript Illumination in the Modern Age : Recovery and Reconstruction, Evanston : Northwestern University, 2001.

- Thomas Coomans & Jan De Maeyer (ed.), The Revival of Mediaeval Illuminating in the Nineteenth Century (KADOC Artes, 9), University Press Leuven, 2007, 336 p.

External links

- Digital Scriptorium

- British Library, Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts

- Initiale - Catalogue de manuscrits enluminés

- Brief Inventory of Illuminated Manuscripts in Herzogenburg/Austria

- Kurzinventar der illuminierten Handschriften in Stift Stams/Austria

- The Illuminated Middle Ages. Several hundred digitized illuminated texts from French national library collections. (commercial)

- Unlocking the Secrets of Medieval Painters and Illuminators

- Central Asian miniature painting

- Armenian miniatures (photos)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)