Antwerp

Antwerp (/ˈæntwɜːrp/ (![]()

![]()

![]()

Antwerp Antwerpen | |

|---|---|

Top: The Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekathedraal (Cathedral of our Lady) and the Scheldt river Bottom: View of the city centre from the top of Museum aan de Stroom | |

.svg.png) Flag .svg.png) Coat of arms | |

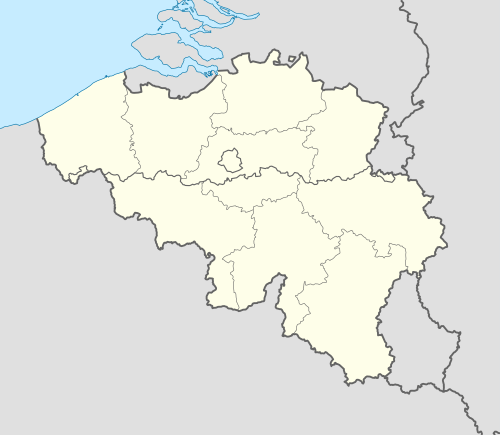

Antwerp Location in Belgium

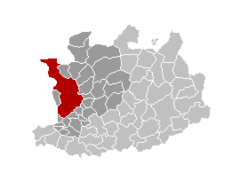

Antwerp municipality in the province of Antwerp  | |

| Coordinates: 51°13′04″N 04°24′01″E | |

| Country | Belgium |

| Community | Flemish Community |

| Region | Flemish Region |

| Province | Antwerp |

| Arrondissement | Antwerp |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (list) | Bart De Wever (N-VA) |

| • Governing party/ies | |

| Area | |

| • Total | 204.51 km2 (78.96 sq mi) |

| Population (2018-01-01)[1] | |

| • Total | 523,248 |

| • Density | 2,600/km2 (6,600/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Antwerpenaar (m) Antwerpse (f) (Dutch) |

| Postal codes | 2000–2660 |

| Area codes | 03 |

| Website | www.antwerpen.be |

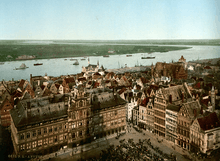

Antwerp is on the River Scheldt, linked to the North Sea by the river's Westerschelde estuary. It is about 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of Brussels, and about 15 kilometres (9 mi) south of the Dutch border. The Port of Antwerp is one of the biggest in the world, ranking second in Europe[5][6] and within the top 20 globally.[7] The city is also known for its diamond industry and trade.

Both economically and culturally, Antwerp is and has long been an important city in the Low Countries, especially before and during the Spanish Fury (1576) and throughout and after the subsequent Dutch Revolt. The Bourse of Antwerp, originally built in 1531 and re-built in 1872, was the world's first purpose-built commodity exchange. It was founded before stocks and shares existed, so was not strictly a stock exchange.[8][9]

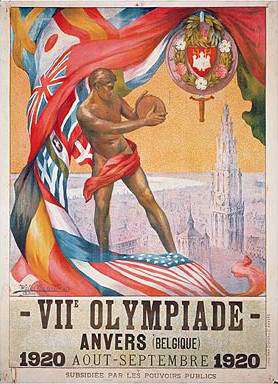

The inhabitants of Antwerp are nicknamed Sinjoren (Dutch pronunciation: [sɪɲˈjoːrə(n)]), after the Spanish honorific señor or French seigneur, "lord", referring to the Spanish noblemen who ruled the city in the 17th century.[10] The city hosted the 1920 Summer Olympics.

History

Origin of the name

%2C_Koninklijk_Museum_voor_Schone_Kunsten_Antwerpen%2C_212.jpg)

Early recorded versions of the name include Ando Verpia on Roman coins found in the city centre,[11] Germanic Andhunerbo from around the time Austrasia became a separate kingdom (that is, about 567 CE),[12] and (possibly originally Celtic) Andoverpis in Dado's Life of St. Eligius (Vita Eligii) from about 700 CE. The form Antverpia is New Latin.[13]

A Germanic (Frankish or Frisian) origin could contain prefix anda ("against") and a noun derived from the verb werpen ("to throw") and denote, for example: land thrown up at the riverbank; an alluvial deposit; a mound (like a terp) thrown up (as a defence) against (something or someone); or a wharf.[14][15][16] If Andoverpis is Celtic in origin, it could mean "those who live on both banks".[17]

There is a folklore tradition that the name Antwerpen is from Dutch handwerpen ("hand-throwing"). A giant called Antigoon is said to have lived near the Scheldt river. He extracted a toll from passing boatmen, severed the hand of anyone who did not pay, and threw it in the river. Eventually the giant was killed by a young hero named Silvius Brabo, who cut off the giant's own hand and flung it into the river. This is unlikely to be the true origin, but it is celebrated by a statue (illustrated further below) in the city's main market square, the Grote Markt.[18][11]

Pre-1500

Historical Antwerp allegedly had its origins in a Gallo-Roman vicus. Excavations carried out in the oldest section near the Scheldt, 1952–1961 (ref. Princeton), produced pottery shards and fragments of glass from mid-2nd century to the end of the 3rd century. The earliest mention of Antwerp dates from the 4th century.

In the 4th century, Antwerp was first named, having been settled by the Germanic Franks.[16]

The Merovingian Antwerp was evangelized by Saint Amand in the 7th century. At the end of the 10th century, the Scheldt became the boundary of the Holy Roman Empire. Antwerp became a margraviate in 980, by the German emperor Otto II, a border province facing the County of Flanders.

In the 11th century, the best-known leader of the First Crusade (1096–1099), Godfrey of Bouillon, was originally Margrave of Antwerp, from 1076 until his death in 1100, though he was later also Duke of Lower Lorraine (1087–1100) and Defender of the Holy Sepulchre (1099–1100). In the 12th century, Norbert of Xanten established a community of his Premonstratensian canons at St. Michael's Abbey at Caloes. Antwerp was also the headquarters of Edward III during his early negotiations with Jacob van Artevelde, and his son Lionel, the Duke of Clarence, was born there in 1338.[19]

16th century

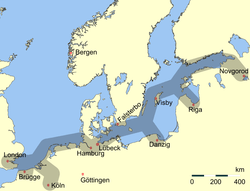

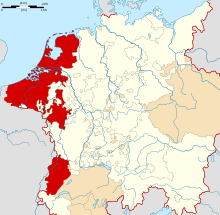

After the silting-up of the Zwin and the consequent decline of Bruges, the city of Antwerp, then part of the Duchy of Brabant, grew in importance. At the end of the 15th century the foreign trading houses were transferred from Bruges to Antwerp, and the building assigned to the association of English merchants active in the city is specifically mentioned in 1510.[19] Antwerp became the sugar capital of Europe, importing the raw commodity from Portuguese and Spanish plantations on both sides of the Atlantic, where it was grown by a mixture of free and forced labour, increasingly enslaved Africans as the century progressed.[20] The city attracted Italian and German sugar refiners by 1550, and shipped their refined product to Germany, especially Cologne.[21] Moneylenders and financiers developed a large business lending money all over Europe including the English government in 1544–1574. London bankers were too small to operate on that scale, and Antwerp had a highly efficient bourse that itself attracted rich bankers from around Europe. After the 1570s, the city's banking business declined: England ended its borrowing in Antwerp in 1574.[22]

Fernand Braudel states that Antwerp became "the centre of the entire international economy, something Bruges had never been even at its height."[23] Antwerp was the richest city in Europe at this time.[24] Antwerp's Golden Age is tightly linked to the "Age of Exploration". During the first half of the 16th century Antwerp grew to become the second-largest European city north of the Alps. Many foreign merchants were resident in the city. Francesco Guicciardini, the Florentine envoy, stated that hundreds of ships would pass in a day, and 2,000 carts entered the city each week. Portuguese ships laden with pepper and cinnamon would unload their cargo. According to Luc-Normand Tellier "It is estimated that the port of Antwerp was earning the Spanish crown seven times more revenues than the Spanish colonization of the Americas".[25]

Without a long-distance merchant fleet, and governed by an oligarchy of banker-aristocrats forbidden to engage in trade, the economy of Antwerp was foreigner-controlled, which made the city very cosmopolitan, with merchants and traders from Venetian Republic, Republic of Genoa, Republic of Ragusa, Spain and Portugal. Antwerp had a policy of toleration, which attracted a large crypto-Jewish community composed of migrants from Spain and Portugal.[26]

By 1504, the Portuguese had established Antwerp as one of their main shipping bases, bringing in spices from Asia and trading them for textiles and metal goods. The city's trade expanded to include cloth from England, Italy and Germany, wines from Germany, France and Spain, salt from France, and wheat from the Baltic. The city's skilled workers processed soap, fish, sugar, and especially cloth. Banks helped finance the trade, the merchants, and the manufacturers. The city was a cosmopolitan center; its bourse opened in 1531, "To the merchants of all nations."[27]

Antwerp experienced three booms during its golden age: the first based on the pepper market, a second launched by American silver coming from Seville (ending with the bankruptcy of Spain in 1557), and a third boom, after the stabilising Treaty of Cateau-Cambresis in 1559, based on the textiles industry. At the beginning of the 16th century Antwerp accounted for 40% of world trade.[25] The boom-and-bust cycles and inflationary cost-of-living squeezed less-skilled workers. In the century after 1541, the city's economy and population declined dramatically The Portuguese merchants left in 1549, and there was much less trade in English cloth. Numerous financial bankruptcies began around 1557. Amsterdam replaced Antwerp as the major trading center for the region.[28]

Reformation era

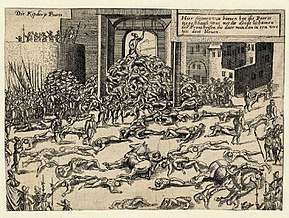

The religious revolution of the Reformation erupted in violent riots in August 1566, as in other parts of the Low Countries. The regent Margaret, Duchess of Parma, was swept aside when Philip II sent the Duke of Alba at the head of an army the following summer. When the Eighty Years' War broke out in 1568, commercial trading between Antwerp and the Spanish port of Bilbao collapsed and became impossible. On 4 November 1576, Spanish soldiers sacked the city during the so-called Spanish Fury: 7,000 citizens were massacred, 800 houses were burnt down, and over £2 million sterling of damage was done.

Dutch revolt

Subsequently, the city joined the Union of Utrecht in 1579 and became the capital of the Dutch Revolt. In 1585, Alessandro Farnese, Duke of Parma and Piacenza, captured it after a long siege and as part of the terms of surrender its Protestant citizens were given two years to settle their affairs before quitting the city.[29] Most went to the United Provinces in the north, starting the Dutch Golden Age. Antwerp's banking was controlled for a generation by Genoa, and Amsterdam became the new trading centre.

17th–19th centuries

.jpg)

.jpg)

The recognition of the independence of the United Provinces by the Treaty of Münster in 1648 stipulated that the Scheldt should be closed to navigation, which destroyed Antwerp's trading activities. This impediment remained in force until 1863, although the provisions were relaxed during French rule from 1795 to 1814, and also during the time Belgium formed part of the Kingdom of the United Netherlands (1815 to 1830).[19] Antwerp had reached the lowest point in its fortunes in 1800, and its population had sunk to under 40,000, when Napoleon, realizing its strategic importance, assigned funds to enlarge the harbour by constructing a new dock (still named the Bonaparte Dock) and an access- lock and mole and deepening the Scheldt to allow for larger ships to approach Antwerp.[24] Napoleon hoped that by making Antwerp's harbour the finest in Europe he would be able to counter the Port of London and hamper British growth. However, he was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo before he could see the plan through.[30] In 1830, the city was captured by the Belgian insurgents, but the citadel continued to be held by a Dutch garrison under General David Hendrik Chassé. For a time Chassé subjected the town to periodic bombardment which inflicted much damage, and at the end of 1832 the citadel itself was besieged by the French Northern Army commanded by Marechal Gerard. During this attack the town was further damaged. In December 1832, after a gallant defence, Chassé made an honourable surrender, ending the Siege of Antwerp (1832).[19]

Later that century, a double ring of Brialmont Fortresses was constructed some 10 km (6 mi) from the city centre, as Antwerp was considered vital for the survival of the young Belgian state. And in 1894 Antwerp presented itself to the world via a World's Fair attended by 3 million.[31]

20th century

Antwerp was the first city to host the World Gymnastics Championships, in 1903. During World War I, the city became the fallback point of the Belgian Army after the defeat at Liège. The Siege of Antwerp lasted for 11 days, but the city was taken after heavy fighting by the German Army, and the Belgians were forced to retreat westwards. Antwerp remained under German occupation until the Armistice.

Antwerp hosted the 1920 Summer Olympics.

During World War II, the city was an important strategic target because of its port. It was occupied by Germany in May 1940 and liberated by the British 11th Armoured Division on 4 September 1944. After this, the Germans attempted to destroy the Port of Antwerp, which was used by the Allies to bring new material ashore. Thousands of Rheinbote, V-1 and V-2 missiles were fired (more V-2s than used on all other targets during the entire war combined), causing severe damage to the city but failed to destroy the port due to poor accuracy. After the war, Antwerp, which had already had a sizeable Jewish population before the war, once again became a major European centre of Haredi (and particularly Hasidic) Orthodox Judaism.

A Ten-Year Plan for the port of Antwerp (1956–1965) expanded and modernized the port's infrastructure with national funding to build a set of canal docks. The broader aim was to facilitate the growth of the north-eastern Antwerp metropolitan region, which attracted new industry based on a flexible and strategic implementation of the project as a co-production between various authorities and private parties. The plan succeeded in extending the linear layout along the Scheldt river by connecting new satellite communities to the main strip.[32]

Starting in the 1990s, Antwerp rebranded itself as a world-class fashion centre. Emphasizing the avant-garde, it tried to compete with London, Milan, New York and Paris. It emerged from organized tourism and mega-cultural events.[33]

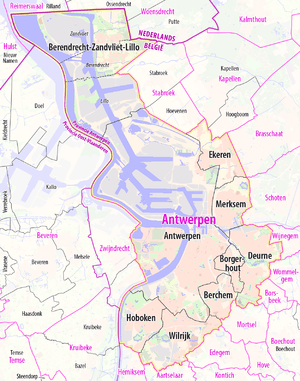

Municipality

The municipality comprises the city of Antwerp proper and several towns. It is divided into nine entities (districts):

In 1958, in preparation of the 10-year development plan for the Port of Antwerp, the municipalities of Berendrecht-Zandvliet-Lillo were integrated into the city territory and lost their administrative independence. During the 1983 merger of municipalities, conducted by the Belgian government as an administrative simplification, the municipalities of Berchem, Borgerhout, Deurne, Ekeren, Hoboken, Merksem and Wilrijk were merged into the city. At that time the city was also divided into the districts mentioned above. Simultaneously, districts received an appointed district council; later district councils became elected bodies.[34]

Buildings and landmarks

In the 16th century, Antwerp was noted for the wealth of its citizens ("Antwerpia nummis"). The houses of these wealthy merchants and manufacturers have been preserved throughout the city. However, fire has destroyed several old buildings, such as the house of the Hanseatic League on the northern quays, in 1891. During World War II, the city also suffered considerable damage from V-bombs, and in recent years, other noteworthy buildings have been demolished for new developments.

- Antwerp Zoo opened in 1843 and is one of the oldest in the world.

- Antwerp City Hall dates from 1565, and is built primarily in Renaissance style.

- Antwerp Central Station is a railway station designed by Louis Delacenserie which was completed in 1905.

- Cathedral of Our Lady. This church was begun in the 14th century and finished in 1518. The church has four works by Rubens, viz. "The Descent from the Cross", "The Elevation of the Cross", "The Resurrection of Christ" and "The Assumption"[19]

- St. James' Church, is more ornate than the cathedral. It contains the remains of numerous famous nobles, among them a major part of the family of Rubens.

- The Church of St. Paul has a baroque interior. It is a few hundred yards north of the Grote Markt

- St. Andrew's Church

- St. Charles Borromeo Church

- Museum Vleeshuis (Butchers' Hall) is a fine Gothic brick-built building, situated a short distance to the North-West of the Grote Markt.

- Plantin-Moretus Museum preserves the house of the printer Christoffel Plantijn and his successor Jan Moretus

- The Saint-Boniface Church is an Anglican church and headseat of the archdeanery North-West Europe.

- Boerentoren (Farmers' Tower) or KBC Tower, a 26-storey building built in 1932, is the oldest skyscraper in Europe.[35] It is the tallest building in Antwerp and the second tallest structure after the Cathedral of our Lady. The building was designed by Emiel van Averbeke, R. Van Hoenacker and Jos Smolderen.[36]

- Royal Museum of Fine Arts

- Museum Mayer van den Bergh, with works from the Gothic and Renaissance period in the Netherlands and Belgium, including paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Elder.

- Rubenshuis is the former home and studio of Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) in Antwerp. It is now a museum.

- Rockox House is the former 17th-century Residence of Nicolaas II Rockox, lord Mayor of Antwerp.

- Bourse of Antwerp. Originally built 1531; extensively restored 1872; now Antwerp Trade Fair.

- Palace of Justice, designed by the Richard Rogers Partnership, Arup and VK Studio, and opened by King Albert II, in April 2006.[37][38] This building is the antithesis of the heavy, dark court building, designed by Joseph Poelaert, which dominates the skyline of Brussels. The courtrooms sit on top of six fingers that radiate from an airy central hall, and are surmounted by spires, which provide north light and resemble oast houses or the sails of barges on the nearby River Scheldt. It is built on the site of the old Zuid ("South") station, at the end of a magnificent 1.5 kilometres (1 mile) perspective at the southern end of Amerikalei. The road neatly disappears into an underpass under oval Bolivarplaats to join the motorway ring. This leaves peaceful surface access by foot, bicycle or tram (route 12). The building's highest 'sail' is 51 m (167 ft) high, has a floor area of 77,000 m2 (830,000 sq ft), and cost €130 million.

- Zurenborg, a late-19th-century Belle Époque neighbourhood, on the border of Antwerp and Berchem, with many Art Nouveau architectural elements. The area counts as one of the most original Belle Époque urban expansion areas in Europe.

- Museum aan de Stroom

- Den Botaniek or Antwerp's Botanical Garden, created in 1825. Located in the city centre, at the Leopoldstraat, it covers an area of almost 1 hectare.

- Harmonium Art museuM, a museum on pump organs in Klein-Willebroek

- Museum of Contemporary Art (M HKA)

Fortifications

Although Antwerp was formerly a fortified city, hardly anything remains of the former enceinte, only some remains of the city wall can be seen near the Vleeshuis museum at the corner of Bloedberg and Burchtgracht. A replica of a castle named Steen has been partly rebuilt near the Scheldt-quais in the 19th century. Antwerp's development as a fortified city is documented between the 10th and the 20th century. The fortifications were developed in different phases:

- 10th century: fortification of the wharf with a wall and a ditch

- 12th and 13th century: canals (so called "vlieten" and "ruien") were made

- 16th century: Spanish fortifications

- 19th century: double ring of Brialmont forts around the city, dismantling of the Spanish fortifications

- 20th century: 1960 dismantling of the inner ring of forts, decommissioning of the outer ring of forts

Demographics

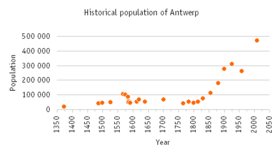

Historical population

This is the population of the city of Antwerp only, not of the larger current municipality of the same name.

|

|

Minorities

| Nationality (by citizenship) | Population – 2020 (all districts)[51] |

| 415,747 | |

| 20,103 | |

| 11,780 | |

| 8,387 | |

| 6,221 | |

| 4,539 | |

| 4,376 | |

| 4,360 | |

| 4,131 | |

| 3,082 | |

| 3,043 | |

| 2,894 | |

| 2,389 | |

| 2,322 | |

| 2,017 | |

| Others | 34,659 |

In 2010, 36% to 39% of the inhabitants of Antwerp had a migrant background. A study projects that in 2020, 55% of the population will be of migrant background.[52][53]

Jewish community

After The Holocaust and the murder of its many Jews, Antwerp became a major centre for Orthodox Jews. At present, about 15,000 Haredi Jews, many of them Hasidic, live in Antwerp. The city has three official Jewish Congregations: Shomrei Hadass, headed by Rabbi Dovid Moishe Lieberman, Machsike Hadass, headed by Rabbi Aron Schiff (formerly by Chief Rabbi Chaim Kreiswirth) and the Portuguese Community Ben Moshe. Antwerp has an extensive network of synagogues, shops, schools and organizations. Significant Hasidic movements in Antwerp include Pshevorsk, based in Antwerp, as well as branches of Satmar, Belz, Bobov, Ger, Skver, Klausenburg, Vizhnitz and several others. Rabbi Chaim Kreiswirth, chief rabbi of the Machsike Hadas community, who died in 2001, was arguably one of the better known personalities to have been based in Antwerp. An attempt to have a street named after him has received the support of the Town Hall and is in the process of being implemented.

Jain community

The Jains in Belgium are estimated to be around about 1,500 people. The majority live in Antwerp, mostly involved in the very lucrative diamond business.[54] Belgian Indian Jains control two-thirds of the rough diamonds trade and supplied India with roughly 36% of their rough diamonds.[55] A major temple, with a cultural centre, has been built in Antwerp (Wilrijk). Mr Ramesh Mehta, a Jain, is a full-fledged member of the Belgian Council of Religious Leaders, put up on 17 December 2009.

Armenian community

There are significant Armenian communities that reside in Antwerp, many of them are descendants of traders who settled during the 19th century. Most Armenian Belgians are adherents of the Armenian Apostolic Church, with a smaller numbers are adherents of the Armenian Catholic Church and Armenian Evangelical Church.

One of the important sectors that Armenian communities in Antwerp excel and involved in is the diamond trade business,[56][57][58][59] that based primarily in the diamond district.[60][61][62] Some of the famous Armenian families involved in the diamond business in the city are the Artinians, Arslanians, Aslanians, Barsamians and the Osganians.[63][64]

Economy

Port

According to the American Association of Port Authorities, the port of Antwerp was the seventeenth largest (by tonnage) port in the world in 2005 and second only to Rotterdam in Europe. It handled 235.2 million tons of cargo in 2018. Importantly it handles high volumes of economically attractive general and project cargo, as well as bulk cargo. Antwerp's docklands, with five oil refineries, are home to a massive concentration of petrochemical industries, second only to the petrochemical cluster in Houston, Texas. Electricity generation is also an important activity, with four nuclear power plants at Doel, a conventional power station in Kallo, as well as several smaller combined cycle plants. There is a wind farm in the northern part of the port area. There are plans to extend this in the period 2014–2020.[65] The old Belgian bluestone quays bordering the Scheldt for a distance of 5.6 km (3.5 mi) to the north and south of the city centre have been retained for their sentimental value and are used mainly by cruise ships and short sea shipping.

Diamonds

Antwerp's other great mainstay is the diamond trade that takes place largely within the diamond district.[66] 85 percent of the world's rough diamonds pass through the district annually,[67] and in 2011 turnover in the industry was $56 billion.[68] The city has four diamond bourses: the Diamond Club of Antwerp, the Beurs voor Diamanthandel, the Antwerpsche Diamantkring and the Vrije Diamanthandel.[69] Antwerp's history in the diamond trade dates back to as early as the sixteenth century,[67] with the first diamond cutters guild being introduced in 1584. The industry never disappeared from Antwerp, and even experienced a second boom in the early twentieth century. By the year 1924, Antwerp had over 13,000 diamond finishers.[70] Since World War II families of the large Hasidic Jewish community have dominated Antwerp's diamond trading industry, although the last two decades have seen Indian[71] and Maronite Christian from Lebanon and Armenian,[60] traders become increasingly important.[71] Antwerp World Diamond Centre, (AWDC) the successor to the Hoge Raad voor Diamant, plays an important role in setting standards, regulating professional ethics, training and promoting the interests of Antwerp as the capital of the diamond industry. However, in recent years Antwerp has seen a downturn in the diamond business, with the industry shifting to cheaper labor markets such as Dubai or India.[72]

Transportation

Road

A six-lane motorway bypass encircles much of the city centre and runs through the urban residential area of Antwerp. Known locally as the "Ring" it offers motorway connections to Brussels, Hasselt and Liège, Ghent, Lille and Bruges and Breda and Bergen op Zoom (Netherlands). The banks of the Scheldt are linked by three road tunnels (in order of construction): the Waasland Tunnel (1934), the Kennedy Tunnel (1967) and the Liefkenshoek Tunnel (1991).

Daily congestion on the Ring led to a fourth high-volume highway link called the "Oosterweelconnection" being proposed. It would have entailed the construction of a long viaduct and bridge (the Lange Wapper) over the docks on the north side of the city in combination with the widening of the existing motorway into a 14-lane motorway; these plans were eventually rejected in a 2009 public referendum.

In September 2010 the Flemish Government decided to replace the bridge by a series of tunnels. There are ideas to cover the Ring in a similar way as happened around Paris, Hamburg, Madrid and other cities. This would reconnect the city with its suburbs and would provide development opportunities to accommodate part of the foreseen population growth in Antwerp which currently are not possible because of the pollution and noise generated by the traffic on the Ring. An old plan to build an R2 outer ring road outside the built up urban area around the Antwerp agglomeration for port related traffic and transit traffic never materialized.

Rail

Antwerp is the focus of lines to the north to Essen and the Netherlands, east to Turnhout, south to Mechelen, Brussels and Charleroi, and southwest to Ghent and Ostend. It is served by international trains to Amsterdam and Paris, and national trains to Ghent, Bruges, Ostend, Brussels, Charleroi, Hasselt, Liège, Leuven and Turnhout.

Antwerp Central station is an architectural monument in itself, and is mentioned in W G Sebald's haunting novel Austerlitz. Prior to the completion in 2007 of a tunnel that runs northwards under the city centre to emerge at the old Antwerp Dam station, Central was a terminus. Trains from Brussels to the Netherlands had to either reverse at Central or call only at Berchem station, 2 kilometres (1 mile) to the south, and then describe a semicircle to the east, round the Singel. Now, they call at the new lower level of the station before continuing in the same direction.

Antwerp is also home to Antwerpen-Noord, the largest classification yard for freight in Belgium and second largest in Europe. The majority of freight trains in Belgium depart from or arrive here. It has two classification humps and over a hundred tracks.

Public transportation

The city has a web of tram and bus lines operated by De Lijn and providing access to the city centre, suburbs and the Left Bank. The tram network has 12 lines, of which the underground section is called the "premetro" and includes a tunnel under the river. The Franklin Rooseveltplaats functions as the city's main hub for local and regional bus lines.

Air

A small airport, Antwerp International Airport, is located in the district of Deurne, with passenger service to various European destinations. A bus service connects the airport to the city centre.

The now defunct VLM Airlines had its head office on the grounds of Antwerp International Airport. This office is also CityJet's Antwerp office.[73][74] When VG Airlines (Delsey Airlines) existed, its head office was located in the district of Merksem.[75]

Belgium's major international airport, Brussels Airport, is about 45 kilometres (28 miles) from the city of Antwerp, and connects the city worldwide. It is connected to the city centre by bus, and also by train. The new Diabolo rail connection provides a direct fast train connection between Antwerp and Brussels Airport as of the summer of 2012.

There is also a direct rail service between Antwerp (calling at Central and Berchem stations) and Charleroi South station, with a connecting buslink to Brussels South Charleroi Airport, which runs twice every hour on working days.

The runway has increased in length, and there is now direct connectivity to Spain, United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, and Greece from the city of Antwerp.

In September 2019 Air Antwerp began operations with their first route to London City Airport with old VLM Airlines Fokker 50's.

Politics

City council

The current city council was elected in the October 2018 elections.

The current majority consists of N-VA, sp.a and Open Vld, led by mayor Bart De Wever (N-VA).

| Party | Seats | |

|---|---|---|

| New Flemish Alliance (N-VA) | 23 | |

| Green | 11 | |

| Socialist Party Differently (sp.a) | 6 | |

| Flemish Interest | 6 | |

| Christian Democratic and Flemish (CD&V) | 3 | |

| Workers' Party of Belgium (PVDA) | 4 | |

| Open Flemish Liberals and Democrats (Open Vld) | 2 | |

| Total | 55 | |

Former mayors

In the 16th and 17th century important mayors include Philips of Marnix, Lord of Saint-Aldegonde, Anthony van Stralen, Lord of Merksem and Nicolaas II Rockox. In the early years after Belgian independence, Antwerp was governed by Catholic-Unionist mayors. Between 1848 and 1921, all mayors were from the Liberal Party (except for the so-called Meeting-intermezzo between 1863 and 1872). Between 1921 and 1932, the city had a Catholic mayor again: Frans Van Cauwelaert. From 1932 onwards and up until 2013, all mayors belonged to the Social Democrat party: Camille Huysmans, Lode Craeybeckx, Frans Detiège and Mathilde Schroyens, and after the municipality fusion: Bob Cools, Leona Detiège en Patrick Janssens. Since 2013, the mayor is the Flemish nationalist Bart De Wever, belonging to the Flemish separatist party N-VA (New Flemish Alliance).

Climate

Antwerp has an oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb) similar to that of Southern England, while being far enough inland to build up summer warmth above 23 °C (73 °F) average highs for both July and August. Winters are more dominated by the maritime currents instead, with temps being heavily moderated.

| Climate data for Antwerp (1981–2010 normals), sunshine 1984–2013 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

7.0 (44.6) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.4 (57.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.1 (73.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

15.3 (59.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

14.7 (58.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

4.0 (39.2) |

10.6 (51.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.7 (33.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

4.8 (40.6) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.7 (53.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.6 (51.1) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.1 (39.4) |

1.5 (34.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69.3 (2.73) |

57.4 (2.26) |

63.8 (2.51) |

47.1 (1.85) |

61.5 (2.42) |

77.0 (3.03) |

80.6 (3.17) |

77.3 (3.04) |

77.2 (3.04) |

78.7 (3.10) |

79.0 (3.11) |

79.5 (3.13) |

848.4 (33.40) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.3 | 10.6 | 12.0 | 9.2 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 10.2 | 9.9 | 10.3 | 11.4 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 132.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 57 | 77 | 122 | 177 | 208 | 202 | 214 | 202 | 144 | 116 | 62 | 47 | 1,625 |

| Source: Royal Meteorological Institute[76] | |||||||||||||

Culture

Antwerp had an artistic reputation in the 17th century, based on its school of painting, which included Rubens, Van Dyck, Jordaens, the Teniers and many others.[19]

Informally, most Antverpians (in Dutch Antwerpenaren, people from Antwerp) speak Antverpian daily (in Dutch Antwerps), a dialect that Dutch-speakers know as distinctive from other Brabantic dialects for its characteristic pronunciation of vowels: an 'aw' sound approximately like that in 'bore' is used for one of its long 'a'-sounds while other short 'a's are very sharp like the 'a' in 'hat'. The Echt Antwaarps Teater ("Authentic Antverpian Theatre") brings the dialect on stage.

Fashion

Antwerp is a rising fashion city, and has produced designers such as the Antwerp Six. The city has a cult status in the fashion world, due to the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, one of the most important fashion academies in the world. It has served as the learning centre for many Belgian fashion designers. Since the 1980s, several graduates of the Belgian Royal Academy of Fine Arts have become internationally successful fashion designers in Antwerp. The city has had a huge influence on other Belgian fashion designers such as Raf Simons, Veronique Branquinho, Olivier Theyskens and Kris Van Assche.[77]

Local products

Antwerp is famous for its local products. In August every year the Bollekesfeest takes place. The Bollekesfeest is a showcase for such local products as Bolleke, an amber beer from the De Koninck Brewery. The Mokatine sweets made by Confiserie Roodthooft, Elixir D'Anvers, a locally made liquor, locally roasted coffee from Koffie Verheyen, sugar from Candico, Poolster pickled herring and Equinox horse meat, are other examples of local specialities. One of the most known products of the city are its biscuits, the Antwerpse Handjes, literally "Antwerp Hands". Usually made from a short pastry with almonds or milk chocolate, they symbolize the Antwerp trademark and folklore. The local products are represented by a non-profit organization, Streekproducten Provincie Antwerpen vzw.

Missions to seafarers

A number of Christian missions to seafarers are based in Antwerp, notably on the Italiëlei. These include the Mission to Seafarers, British & International Sailors' Society, the Finnish Seamen's Mission, the Norwegian Sjømannskirken and the Apostleship of the Sea. They provide cafeterias, cultural and social activities as well as religious services.

Music

Antwerp is the home of the Antwerp Jazz Club (AJC), founded in 1938 and located on the square Grote Markt since 1994.[78]

The band dEUS was formed in 1991 in Antwerp. dEUS began their career as a covers band, but soon began writing their own material. Their musical influences range from folk and punk to jazz and progressive rock.

Music festivals

Cultuurmarkt van Vlaanderen is a musical festival and a touristic attraction that takes place annually on the final Sunday of August in the city center of Antwerp. Where international and local musicians and actors, present their stage and street performances.[79][80][81]

Linkerwoofer is a pop-rock music festival located at the left bank of the Scheldt. This music festival starts in August and mostly local Belgian musicians play and perform in this event.[82][83][84]

Other popular festivals Fire Is Gold, and focuses more on urban music, and Summerfestival.

World Choir Games

The city of Antwerp will co-host the 2020 World Choir Games together with the city of Ghent.[85] Organised by the Interkultur Foundation, the World Choir Games is the biggest choral competition and festival in the world.

Sport

Antwerp held the 1920 Summer Olympics, which were the first games after the First World War and also the only ones to be held in Belgium. The road cycling events took place in the streets of the city.[86][87]

Royal Antwerp F.C., currently playing in the Belgian First Division, were founded in 1880 and is known as 'The Great Old' for being the first club registered to the Royal Belgian Football Association in 1895.[88] Since 1998, the club has taken Manchester United players on loan in an official partnership.[89] Another club in the city was Beerschot VAC, founded in 1899 by former Royal Antwerp players. They played at the Olympisch Stadion, the main venue of the 1920 Olympics. Nowadays KFCO Beerschot Wilrijk plays at the Olympisch Stadion in the Belgian Second Division.

The Antwerp Giants play in Basketball League Belgium and Topvolley Antwerpen play in the Belgium men's volleyball League.

For the year 2013, Antwerp was awarded the title of European Capital of Sport.

Antwerp hosted the 2013 World Artistic Gymnastics Championships.

Antwerp hosted the start of stage 3 of the 2015 Tour de France on 6 July 2015.[90]

Higher education

Antwerp has a university and several colleges. The University of Antwerp (Universiteit Antwerpen) was established in 2003, following the merger of the RUCA, UFSIA and UIA institutes. Their roots go back to 1852. The University has approximately 23,000 registered students, making it the third-largest university in Flanders, as well as 1,800 foreign students. It has 7 faculties, spread over four campus locations in the city centre and in the south of the city.

The city has several colleges, including Antwerp Management School (AMS), Charlemagne University College (Karel de Grote Hogeschool), Plantin University College (Plantijn Hogeschool), and Artesis University College (Artesis Hogeschool). Artesis University College has about 8,600 students and 1,600 staff, and Charlemagne University College has about 10,000 students and 1,300 staff. Plantin University College has approximately 3,700 students.

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

The following places are twinned with or sister cities to Antwerp:

Partnerships

|

Within the context of development cooperation, Antwerp is also linked to

|

Notable people

Born in Antwerp

- Lionel of Antwerp, 1st Duke of Clarence, son of Edward III of England (1338–1368)

- Samuel Blommaert, Director of the Dutch West India Company (1583–1654)

- Frans Floris, painter (1520–1570)

- Abraham Ortelius, cartographer and geographer (1527–98)

- Gillis van Coninxloo, painter of forest landscapes (1544–1607)

- Bartholomeus Spranger, painter, draughtsman, and etcher (1546–1611)

- Martín Antonio del Río, Jesuit theologian (1551–1608)

- Matthijs Bril, landscape painter (1550–1583)

- Balthazar de Moucheron, one of the founders of the Dutch East India Company (VOC)

- Paul Bril, landscape painter (1554–1626)

- Willem Usselincx, Flemish merchant and investor, one of the founders of the Dutch West India Company (1567–1647)

- Abraham Janssens, painter (c. 1570 – 1632)

- Rodrigo Calderón, Count of Oliva, Spanish favourite and adventurer (died 1621)

- Frans Snyders, still life and animal painter (1579–1657)

- Osias Beert the Elder (1580–1623)

- Frans Hals, painter (1580–1666)

- Caspar de Crayer, painter (1582–1669)

- David Teniers the Elder, painter (1582–1649)

- Jacob Jordaens, painter (1593–1678)

- Anthony van Dyck, painter (1599–1641)

- Cornelis Melyn, Early American Settler, Patroon of Staten Island (1600-c. 1662)

- Pieter van Schaeyenborgh, painter of fish still lifes (1600–1657)

- David Teniers the Younger, painter (1610–1690)

- Jan Fyt, animal painter (1611–1661)

- Jacob Leyssens, Baroque painter (1661–1710)

- Nicolaes Maes, Baroque painter (1634–1693)

- Hendrik Abbé, engraver, painter and architect (1639–?)

- Gerard Edelinck, copperplate engraver (1649–1707)

- Peter Tillemans, painter (c. 1684 – 1734)

- John Michael Rysbrack, sculptor (1694–1770)

- Francis Palms, Belgian-American landholder and businessman (1809–1886)

- Hendrik Conscience, writer and author of De Leeuw van Vlaanderen ("The Lion of Flanders") (1812–1883)

- Johann Coaz, Swiss forester, topographer and mountaineer (1822–1918)

- Jef Lambeaux, sculptor of the Brabo fountain in the Grote Markt (1852–1908)

- Georges Eekhoud, novelist (1854–1927)

- Hippolyte Delehaye, Jesuit Priest and hagiographic scholar (1859–1941)

- Ferdinand Perier, Jesuit Priest and 3rd Archbishop of Calcutta (1875–1968)

- Willem Elsschot, writer and poet (1882–1960)

- Jef van Hoof, conductor and composer (1886–1959)

- Constant Permeke, expressionist painter (1886–1952)

- Paul van Ostaijen, poet and writer (1896–1928)

- Alice Nahon, poet (1896–1933)

- Albert Lilar, Minister of Justice (1900–1976)

- Maurice Gilliams, writer (1900–1982)

- Michel Seuphor, painter, designer (1901–1999)

- André Cluytens, conductor (1905–1967)

- Daniel Sternefeld, composer and conductor (1905–1986)

- Maurice van Essche, Belgian-born South African painter (1906–1977)

- Antoinette Feuerwerker, French jurist and member of the Resistance (1912–2003)

- Jean Bingen, Belgian papyrologist and epigrapher (1920–2012)

- Karl Gotch, professional wrestler (1924–2007)

- Simon Kornblit, American advertising and film studio executive (1933–2010)[92]

- Bernard de Walque, architect (born 1938)

- Ferre Grignard, rock singer/songwriter, known for "Ring Ring, I've Got To Sing" (1939–1982)

- Paul Buysse, businessman (born 1945)

- Carl Verbraeken, composer (born 1950)

- Tom Barman, Belgian musician and film director (born 1972)

- Matthias Schoenaerts, actor (born 1977)

- Tia Hellebaut, Olympic high jump champion (born 1978)

- Evi Goffin, vocalist (born 1981)

- Jessica Van Der Steen, model (born 1984)

- Laetitia Beck, Israeli golfer (born 1992)

- Romelu Lukaku, professional Belgian footballer (born 1993)

- Jacoba Hol (1886–1964), physical geographer

- Toby Alderweireld, professional Belgian footballer (born 1989)

Lived in Antwerp

- Erasmus II Schetz, Lord of Grobbendonk

- Abraham Mayer, German-born physician (1848)

- Quentin Matsys, Renaissance painter, founder of the Antwerp school (1466–1530)

- Jan Mabuse, painter (c. 1478–1532)

- Joachim Patinir, landscape and religious painter (c. 1480–1524)

- John Rogers, Christian minister, Bible translator and commentator, and martyr (c. 1500–1555)

- Joos van Cleve, painter (c. 1500–1540/41)

- Damião de Góis, Portuguese humanist philosopher (1502–1574)

- Sir Thomas Gresham, English merchant and financier (c. 1519–1579)

- Sir Anthony More, portrait painter (1520–c. 1577)

- Christoffel Plantijn, humanist, book printer and publisher (c. 1520–1589)

- Pieter Brueghel the Elder, painter and printmaker (1525–1569)

- Philip van Marnix, writer and statesman (1538–1598)

- Simon Stevin, mathematician and engineer (c. 1548/49–1620)

- Federigo Giambelli, Italian military and civil engineer (c. 1550–c. 1610)

- John Bull, English and Welsh composer, musician, and organ builder (c. 1562–1628)

- Jan Brueghel the Elder, also known as "Velvet" Brueghel, painter (1568–1625)

- Pieter Paul Rubens, painter (1577–1640)

- William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle, English soldier, politician, and writer (c. 1592 – 1676)

- Adriaen Brouwer, painter (1605–1638)

- Jan Davidszoon de Heem, painter (1606–1684)

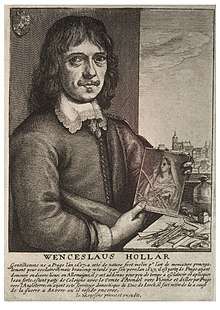

- Wenceslas Hollar, Bohemian etcher (1607–1677)

- Jan Lievens, painter (1607–1674)

- Ferdinand van Apshoven the Younger, painter (c. 1630–1694)

- Frédéric Théodore Faber, painter (1782–1799)

- Jan Frans Willems, writer (1793–1846)

- Henri Alexis Brialmont, military engineer (1821–1903)

- Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, painter (1836–1912)

- Vincent van Gogh, impressionist Dutch painter who lived in Antwerp for about four months (1853–1890)

- Camille Huysmans, Socialist politician, former mayor of Antwerp and former Prime Minister of Belgium (1871–1968)

- Moshe Yitzchok Gewirtzman, leader of the Hasidic Pshevorsk movement based in Antwerp (1881–1976)

- Romi Goldmuntz, businessman (1882–1960)

- Gerard Walschap, writer (1898–1989)

- Albert Lilar, Minister of Justice (1900–1976)

- Suzanne Lilar, essayist, novelist, and playwright (1901–1992)

- Heaven Tanudiredja, designer, artist

- Eric de Kuyper, award-winning novelist, filmmaker, semiotician

- Philip Sessarego, former British Army soldier, conman, hoaxer, mercenary lived in Antwerp and found dead in a garage (1952–2008)

- Jean Genet, French writer and political activist (1909–1986), lived in Antwerp for short period in the 1930s

- George du Maurier, came to Antwerp to study art and lost the sight in one eye; cartoonist, author and grandfather of Daphne du Maurier (1834–1896)

- Chaim Kreiswirth, Talmudist and Rabbi of the Machsike Hadas Community, Antwerp (1918–2001)

- William Tyndale, Bible translator, arrested in Antwerp 1535 and burnt at Vilvoorde in 1536 (c. 1494–1536)

- Akiba Rubinstein, Polish grandmaster of chess (1882–1961).

- Veerle Casteleyn, performer

- Ray Cokes, English TV host

- Robert Barrett Browning, or "Pen", only child of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, studied painting in Antwerp

- Ford Madox Brown, leading Preraphaelite painter. Studied art at Antwerp.

- August De Boodt, politician (1895–1986)

- Nicolaas II Rockox

- Bernoulli family, renowned family of mathematicians and physicists

Select neighbourhoods

- Den Dam – an area in northern Antwerp

- The diamond district – an area consisting of several square blocks, it is Antwerp's centre for the cutting, polishing, and trading of diamonds

- Linkeroever – Antwerp on the left bank of the Scheldt with a lot of apartment buildings

- Meir – Antwerp's largest shopping street

- Van Wesenbekestraat – the city's Chinatown

- Het Zuid – the south of Antwerp, notable for its museums and Expo grounds

- Zurenborg – an area between Central and Berchem station with a concentration of Art Nouveau townhouses

See also

- Antwerp Book Fair

- Antwerp lace

- Antwerp Water Works (AWW)

- Jewish Community of Antwerp

- Letterenhuis

- List of mayors of Antwerp

- Pshevorsk – Hassidic Jewish movement based in Antwerp

- Royal Antwerp F.C., local football club

References

- "Wettelijke Bevolking per gemeente op 1 januari 2018". Statbel. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- Statistics Belgium; Loop van de bevolking per gemeente (excel-file) Population of all municipalities in Belgium, as of 1 January 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- The capital region of Brussels, whose metropolitan area comprises the city itself plus 18 independent communal entities, counts over 1,700,000 inhabitants, but these communities are counted separately by the Belgian Statistics Office Statbel the Belgian statistics office

- "De Belgische Stadsgewesten 2001" (PDF). Statistics Belgium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 19 October 2008. Definitions of metropolitan areas in Belgium.

- http://www.portofantwerp.com/sites/portofantwerp/files/Annual%20Report%202014_EN.pdf Page 14

- "Antwerp is Europe's second largest port". 9 November 2016.

- "The World According to GaWC 2012". Globalization and World Cities (GaWC) Study Group and Network. Loughborough University. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- "Antwerp Bourse—World's Oldest—Closes". Los Angeles Times. 31 December 1997. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

- "A look inside one of the world's oldest stock exchange buildings". Barcroft TV.

- Geert Cole; Leanne Logan, Belgium & Luxembourg p.218 Lonely Planet Publishing (2007) ISBN 1-74104-237-2

- Brabo Antwerpen 1 (centrum) / Antwerpen (in Dutch)

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press – via Wikisource.

|chapter=ignored (help) - German Wiktionary. Retrieved 5 June 2020

- "Kroniek Antwerpen". AVBG (in Dutch). Antwerp Society for Architectural History. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Room, Adrian (1 August 1997). Placenames of the World. McFarland & Company. p. 32. ISBN 0-7864-0172-9.

- "Antwerp" Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Naam Antwerpen heeft keltische oorsprong". Gazet van Antwerpen (in Dutch). 13 September 2007. Retrieved 18 August 2017. For the relevant passage in the Vita Eligii, see the Monumenta Germaniae Historica on the Digital MGH (page 700) retrieved 4 June 2020 (in Latin). Fordham University has published an English translation of the Vita Eligii by Jo Ann McNamara retrieved 18 August 2017

- Legenden en Mythen Legende van Brabo en de reus Antigoon. Archived 1 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine (in Dutch)

-

- Tom Monaghan, Renaissance, Reformation and the Age of Discovery, 1450–1700 (Heinemann, 2002)

- Donald J. Harreld, "Atlantic Sugar and Antwerp's Trade with Germany in the Sixteenth Century," Journal of Early Modern History, 2003, Vol. 7 Issue 1/2, pp 148–163

- Outhwaite, R. B. (1966). "The Trials of Foreign Borrowing: The English Crown and the Antwerp Money Market in the Mid-Sixteenth Century". The Economic History Review. 19 (2): 289–305. doi:10.2307/2592253. JSTOR 2592253.

- (Braudel 1985 p. 143.)

- Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 163.

- Luc-Normand Tellier (2009). "Urban world history: an economic and geographical perspective". PUQ. p.308. ISBN 2-7605-1588-5

- Isidore Singer and Cyrus Adler, eds. (1916). The Jewish Encyclopedia. pp. 658–60.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Peter Gay and R.K. Webb, Modern Europe to 1815 (1973), p. 210.

- Gay and Webb, Modern Europe to 1815 (1973), p. 210-11.

- Boxer Charles Ralph, The Dutch seaborne empire, 1600–1800, p. 18, Taylor & Francis, 1977 ISBN 0-09-131051-2, ISBN 978-0-09-131051-6 Google books

- Dunton, Larkin (1896). The World and Its People. Silver, Burdett. p. 164.

- Pelle, Kimberley D (2008). Findling, John E (ed.). Encyclopedia of World's Fairs and Expositions. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-7864-3416-9.

- Michael Ryckewaert, Planning Perspectives, July 2010, Vol. 25 Issue 3, pp 303–322,

- Javier Gimeno Martínez, "Selling Avant-garde: How Antwerp Became a Fashion Capital (1990–2002)," Urban Studies November 2007, Vol. 44 Issue 13, pp 2449–2464

- De Ceuninck, Koenraad (2009). De gemeentelijke fusies van 1976. Een mijlpaal voor de lokale besturen in België. Die keure, Brugge.

- Emporis. Retrieved 23 October 2006.

- "KBC Tower – The Skyscraper Center". skyscrapercenter.com. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "Palace of Justice in Antwerp". uginox.com. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "Divine justice". The Guardian. 10 April 2006. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "Antwerp timeline 1300–1399". Strecker.be. Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- "Antwerp timeline 1400–1499". Strecker.be. Archived from the original on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- Braudel, Fernand The Perspective of the World, 1985

- "Antwerp timeline 1500–1599". Strecker.be. Archived from the original on 2 May 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- Coornaert, Émile (1961). Les Français et le commerce international à Anvers : fin du XVe, XVIe siècle. Paris: Marcel Rivière et cie. p. 96.

- Boumans, R; Craeybeckx, J (1947). Het bevolkingscijfer van Antwerpen in het derde kwart der XVIe eeuw. T.G. pp. 394–405.

- van Houtte, J. A. (1961). "Anvers aux XVe et XVIe siècles : expansion et apogée". Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations. 16 (2): 249. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- Description of the French Fury matter, see chapter 'Declaration of independence' in article 'William the Silent'

- "Antwerp timeline 1600–1699". Strecker.be. Archived from the original on 7 May 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- "Antwerp timeline 1700–1799". Strecker.be. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- "Antwerp timeline 1800–1899". Strecker.be. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- "Antwerp timeline 1900–1999". Strecker.be. Archived from the original on 7 January 2008. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- "Stad in Cijfers – Databank – Inwoners naar nationaliteit, leeftijd, (8 klassen) en geslacht 2020 – Antwerpen". Antwerpen.be. City of Antwerp. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Auteur: Dajo Hermans. "56 procent van Antwerpse kinderen is allochtoon – Het Nieuwsblad". Nieuwsblad.be. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Antwerpen in 2020 voor 55% allochtoon" (in Dutch). Express.be. 17 May 2010. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "An Introduction to Jainism: History, Religion, Gods, Scriptures and Beliefs". Commisceo Global. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Daneels, Door Gilbert Roox, foto's Wim. "Diamant met curry". De Standaard (in Dutch). Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- Inside Knowledge: Streetwise in Asia p.163

- Vanneste, Tijl (6 October 2015). Global Trade and Commercial Networks: Eighteenth-Century Diamond Merchants. Routledge. ISBN 9781317323372 – via Google Books.

- Indians shine antwerp diamond centre polls International Business Times

- Belgium Real Estate Yearbook 2009 p.23

- Recession takes the sparkle out of Antwerp's diamond quarter |World news. The Guardian. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- "Antwerp and diamonds, the facts – Baunat Diamonds". baunatdiamonds.com.

- The Global Diamond Industry: Economics and Development, Volume 2 p.3.6

- "THE ARMENIAN OF BELGIUM: AN UNINTERRUPTED PRESENCE SINCE THE 4TH CENTURY". AGBU – Armenian non-profit organization.

- "Armenia: Report on Kotayk Province". WikiLeaks. 26 August 2011. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- "Wind farm | Sustainable Port of Antwerp". Archived from the original on 30 April 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- John Tagliabue (5 November 2012). "An Industry Struggles to Keep Its Luster". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- "Diamond". Business in Antwerp. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- Tagliabue, John (2012). "An Industry Struggles to Keep Its Luster". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- "The industry | Antwerp World Diamond Centre". awdc.be. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Hofmeester, Karin (March 2013). "Shifting trajectories of diamond processing: from India to Europe and back, from the fifteenth century to the twentieth*". Journal of Global History. 8 (1): 25–49. doi:10.1017/S174002281300003X. ISSN 1740-0228.

- "WSJ: Indians Unseat Antwerp's Jews As the Biggest Diamond Traders". Stefangeens.com. 27 May 2003. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- Simons, Marlise (1 January 2006). "Twilight in Diamond Land: Antwerp's Loss, India's Gain". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 April 2019.

- "Your VLM contacts". Archived from the original on 1 August 2003. Retrieved 29 March 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) VLM Airlines. 1 August 2003. Retrieved 6 July 2010. "Headquarters VLM Airlines Belgium NV Luchthavengebouw B50 B 2100 Deurne Antwerpen."

- "Our Offices Archived 14 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine." CityJet. Retrieved 6 July 2010. "Antwerp office VLM Airlines Belgium NV Luchthavengebouw B50 B 2100 Antwerp Belgium Company registration number 0446.670.251."

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 December 2002. Retrieved 3 December 2002.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Delsey Airlines. 3 December 2002. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- "Statistiques climatiques des communes belges: Antwerpen (ins 11002)" (PDF) (in French). Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- Martínez (2007). Selling Avant-garde: How Antwerp Became a Fashion Capital (1990–2002).

- "Verenigingen gevestigd in 'Den Bengel'. ANTWERPSE JAZZCLUB". Cafe Den Bengel. 27 February 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "Gratis klassiek festival in Antwerpen". De Morgen (in Dutch). Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- http://www.103.be, Firma 103 -. "cultuurmarkt van vlaanderen – nieuws". cultuurmarkt.be. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Geert Geerits (11 December 2017), Cultuurmarkt Antwerpen, retrieved 24 January 2018

- "Linkerwoofer 2018". linkerwoofer.be. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "Linkerwoofer". visitantwerpen.be. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "stubru.be". stubru.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- "Double gold for next host country of the World Choir Games 2020". interkultur.com. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- "Cycling at the 1920 Antwerpen Summer Games: Men's Road Race, Individual | Olympics at Sports-Reference.com". sports-reference.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- Sports-reference.com 1920 Summer Olympics cycling team road race, team Olympics at Sports-Reference.com

- "ROYAL ANTWERP FOOTBALL CLUB". Archived from the original on 3 July 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Manchester United's Royal Antwerp Loanees Archived 2 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Five Cantonas

- "Tour de France 2015 : de l'eau, et du diamant" (in French). letour.fr. 24 May 2014. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- "Akhisar Belediyesi – ATİK – UEMP". uemp.eu. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- Grossblat, R.M. (15 July 2010). "Simon Korblit, a Profile Tribute". Atlanta Jewish News. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

Further reading

- Blanchard, Ian. The International Economy in the "Age of the Discoveries," 1470–1570: Antwerp and the English Merchants' World (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009). 288 pp. in English

- Harreld, Donald J. "Trading Places," Journal of Urban History (2003) 29#6 pp 657–669

- Lindemann, Mary. The Merchant Republics: Amsterdam, Antwerp, and Hamburg, 1648–1790 (Cambridge University Press, 2014) 356 pp.

- Limberger, Michael. Sixteenth-Century Antwerp and its Rural Surroundings: Social and Economic Changes in the Hinterland of a Commercial Metropolis (ca. 1450–1570) (Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2008). 284 pp. ISBN 978-2-503-52725-3.

- Makos, Adam (2019). Spearhead (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 63, 69. ISBN 9780804176729. LCCN 2018039460. OL 27342118M.

- Stillwell, Richard, ed. Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, 1976: "Antwerp Belgium"

- Van der Wee, Herman. The Growth of the Antwerp Market and the European Economy (14th–16th Centuries) (The Hague, 1963)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Antwerp. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Antwerp. |

.jpg)

_pictogram.svg.png)