Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees, (French: Traité des Pyrénées, Spanish: Tratado de los Pirineos, Catalan: Tractat dels Pirineus), was signed on 7 November 1659, and ended the 1635 to 1659 Franco-Spanish war.[1]

Louis XIV and Philip IV of Spain at the Meeting on the Isle of Pheasants, June 1660 | |

| Context | Spain and France end the 1635–1659 war; Spain cedes Artois and Northern Catalonia; Louis marries Maria Theresa of Spain |

|---|---|

| Signed | 7 November 1659 |

| Location | Pheasant Island |

| Negotiators | |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

Negotiations were conducted on Pheasant Island, situated in the middle of the Bidasoa river on the border between the two countries, which has remained a French-Spanish condominium ever since. It was signed by Louis XIV of France and Philip IV of Spain, as well as their chief ministers, Cardinal Mazarin and Don Luis Méndez de Haro.[2]

Background

France entered the Thirty Years' War after the Spanish Habsburg victories in the Dutch Revolt in the 1620s and at the Battle of Nördlingen against Sweden in 1634. By 1640, France began to interfere in Spanish politics, aiding the revolt in Catalonia, while Spain responded by aiding the Fronde revolt in France in 1648. During the negotiations for the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, France gained the Sundgau and cut off Spanish access to the Netherlands from Austria, leading to open warfare between the French and Spanish.

After 23 years of war, an Anglo-French alliance was victorious at the Battle of the Dunes in 14 June 1658, but the following year the war ground to a halt when the French campaign to take Milan was defeated. Peace was settled by means of the Treaty of the Pyrenees in November 1659.

Content

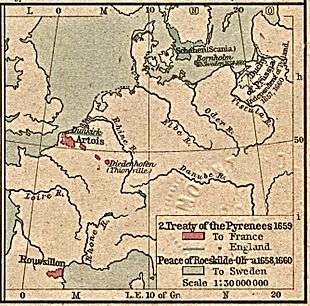

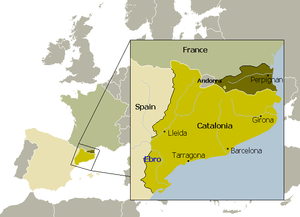

France gained Roussillon (including Perpignan) and the northern half of Cerdanya, Montmédy and other parts of Luxembourg, Artois and other towns in Flanders, including Arras, Béthune, Gravelines and Thionville, and a new border with Spain was fixed at the Pyrenees.[3] However, the treaty stipulated only that all "villages" north of the Pyrenees should become part of France. Because it was a villa, the historic town of Llívia, once the capital of Cerdanya, was thus unintentionally exempted from the treaty and became a Spanish exclave as part of the comarca of Baixa Cerdanya, in the Spanish province of Girona. This border was not properly settled until the Treaty of Bayonne was signed in 1856, with its final acts accepted 12 years later. On the western Pyrenees a definite borderline was drawn and decisions made as to the politico-administrative affiliation of bordering areas in the Basque region—Baztan, Aldude, Valcarlos.

Spain was forced to recognize and confirm all of the French gains at the Peace of Westphalia.[3] In exchange for the Spanish territorial losses, the French king pledged to quit his support for Portugal and renounced his claim to the county of Barcelona, which the French crown had claimed ever since the Catalan Revolt (also known as Reapers' War).[3] The Portuguese revolt in 1640, led by the Duke of Braganza, was supported monetarily by Cardinal Richelieu of France. After the Catalan Revolt, France had controlled the Principality of Catalonia from January 1641, when a combined Catalan and French force defeated the Spanish army at Battle of Montjuïc, until it was defeated by a Spanish army at Barcelona in 1652.[5] Though the Spanish army reconquered most of Catalonia, the French retained Catalan territory north of the Pyrenees.

The treaty also arranged for a marriage between Louis XIV of France and Maria Theresa of Spain, the daughter of Philip IV of Spain.[3] Maria Theresa was forced to renounce her claim to the Spanish throne, in return for a monetary settlement as part of her dowry. This settlement was never paid, a factor that eventually led to the War of Devolution in 1668. At the Meeting on the Isle of Pheasants in June 1660, the two monarchs and their ministers met, and the princess entered France.

In addition, the English received Dunkirk,[3] although they elected to sell it to France in 1662.

Consequences

The Treaty of the Pyrenees was the last major diplomatic achievement by Cardinal Mazarin. Combined with the Peace of Westphalia, it allowed Louis XIV remarkable stability and diplomatic advantage by means of a weakened Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé and a weakened Spanish Crown, along with the agreed dowry, which was an important element in the French king's strategy:

All in all, by 1660, when the Swedish occupation of Poland was over, most of the European continent was at peace (though the third stage of the Portuguese Restoration War would soon begin), and the Bourbons had ended the dominance of the Habsburgs.[6] In the Pyrenees, the treaty resulted in the establishment of border customs and restriction of the free cross-border flow of people and goods. The treaty also settled indefinitely the century and half long litigation over the Kingdom of Navarre, while the dispute over the Aldudes remained in place still throughout the 18th century.

French annexations

In the context of the territorial changes involved in the Treaty, France gained some territory, on both its northern and southern borders.

- In the north, France gained French Flanders.

- In the south:

- On the east: The northern part of the Principality of Catalonia, including Roussillon, Conflent, Vallespir, Capcir, and French Cerdagne, was transferred to France, i.e. what later came to be known as "Northern Catalonia".

- On the west: The parties agree to put together a field group to compromise a borderline on disputed lands along the Basque Pyrenees, involving Sareta—Zugarramurdi, Ainhoa, etc.— Aldude, and the Spanish wedge of Valcarlos.

See also

- Language policy in France

- Parliament of Quillín

References

- Cooper 1970, p. 428.

- Sahlins 1989, p. 25.

- Maland 1966, p. 227.

- Pendrill 2002, pp. 142–143.

- Oakley 1993, pp. 84-85.

Sources

- Cooper, JP (editor) (1970). The New Cambridge Modern History: Volume 4, The Decline of Spain and the Thirty Years War, 1609-48/49: (1979 ed.). CUP. ISBN 978-0521076180.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maland, David (1966). Europe in the Seventeenth Century (1991 ed.). Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333023419.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Monreal, Gregorio; Jimeno, Roldan (2012). Conquista e Incorporación de Navarra a Castilla. Pamplona-Iruña: Pamiela. ISBN 978-84-7681-736-0.

- Pendrill, Colin (2002). Martin Collier, Erica Lewis (ed.). Spain 1474 - 1700. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-435-32733-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sahlins, Peter (1989). Boundaries: The Making of France and Spain in the Pyrenees (1992 ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520065383.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oakley, Stewart P (1993). War and Peace in the Baltic, 1560-1790 (2005 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0415024723.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- "Full Text of Treaty" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2005. (16.8 MiB), France National Archives Transcription (in French)