Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Neapolitan: Regno d’ ’e Ddoje Sicilie; Sicilian: Regnu dî Dui Sicili; Italian: Regno delle Due Sicilie; Spanish: Reino de las Dos Sicilias)[1] was a kingdom located in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860.[2] The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy prior to Italian unification, comprising Sicily and all of Peninsula Italy south of the Papal States, covering most of the area of today's Mezzogiorno.

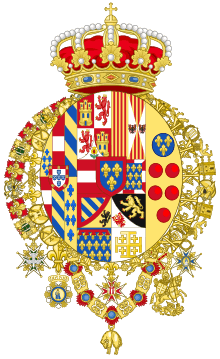

Kingdom of the Two Sicilies Regno delle Due Sicilie | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1816–1861 | |||||||||||

.svg.png) Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Palermo (1816–1817) Naples (1817–1861) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Administrative: Italian and Latin In use: Neapolitan and Sicilian language | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Sicilian | ||||||||||

| Government | Absolute Monarchy (1816-1848,1849-1861) | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 1816–1825 | Ferdinand I | ||||||||||

• 1825–1830 | Francis I | ||||||||||

• 1830–1859 | Ferdinand II | ||||||||||

• 1859–1861 | Francis II | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Founded | 1816 | ||||||||||

| 1815 | |||||||||||

| 1860 | |||||||||||

• Annexed by Kingdom of Sardinia | 1861 | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

| 1851 | 111,900 km2 (43,200 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1851 | 8,704,472 | ||||||||||

• 1859 | 9,281,279 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Two Sicilies ducat | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Italy | ||||||||||

The kingdom was formed when the Kingdom of Sicily merged with the Kingdom of Naples, which was officially known as the Kingdom of Sicily. Since both kingdoms were named Sicily, they were collectively known as the "Two Sicilies" (Utraque Sicilia, literally "both Sicilies"), and the unified kingdom adopted this name. The King of the Two Sicilies was overthrown by Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1860, after which the people voted in a plebiscite to join the Savoyard Kingdom of Sardinia. The annexation of the Two Sicilies completed the first phase of Italian unification, and the new Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed in 1861.

The Two Sicilies were heavily agricultural, like the other Italian states.[3]

Name

The name "Two Sicilies" originated from the partition of the medieval Kingdom of Sicily. Until 1285, the island of Sicily and the Mezzogiorno were constituent parts of the Kingdom of Sicily. As a result of the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302),[4] the King of Sicily lost the Island of Sicily (also called Trinacria) to the Crown of Aragon, but remained ruler over the peninsular part of the realm. Although his territory became known unofficially as the Kingdom of Naples, he and his successors never gave up the title "King of Sicily" and still officially referred to their realm as the "Kingdom of Sicily". At the same time, the Aragonese rulers of the Island of Sicily also called their realm the "Kingdom of Sicily". Thus, there were two kingdoms called "Sicily":[4] hence, the Two Sicilies.

Background

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily was established on Christmas Day, 1130, by Roger II of Sicily who united the lands he had inherited which included the Duchy of Apulia and the County of Sicily with the agreement of Pope Innocent II. In 1282, following the Sicilian Vespers, it was split into the Kingdoms of Sicily and of Naples by the Peace of Caltabellotta. From 1442 onward Sicily and Naples were in dynastic union, by the Crown of Aragon, since 1516 by the Habsburg Dynasty (since 1556 Spanish line). After the War of Spanish Succession, Spain ceded Sicily to Savoy and Naples to Austria. After the War of the Quadruple Alliance, Austria and Savoy switched Sicily (now to Austria) for Sardinia (now to Savoy, 1720). Austrian rule in Naples and Sicily was ended by a Spanish invasion in 1734. The Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily had been under joint rule from 1442 to 1718 and from 1720 to 1734.

1734-1759

In the War of Polish Succession (1733-1735), Spain, now under the Bourbon Dynasty, regained the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily, which had been lost to Austria and Savoy respectively in the War of Spanish Succession (1700-1713). In the Treaty of Vienna (1738) Austria ceded both Sicily and Naples to Spain in return for the Duchy of Parma. The Bourbon Dynasty of Spain created a secundogeniture under Charles for both Sicily and Naples united. Under King Charles (1735/38-1759) and under minister Tanucci, Naples became a center of the Enlightenment. In the spirit of religious toleration, Jews, banned from Naples since 1541, were readmitted in 1735. King Charles reformed the army and improved the roads. When an English fleet threatened the Neapolitan coast in 1742, during the War of Austrian Succession, the Kingdom hastily declared neutrality. Later during the same war, in 1744, an Austrian invasion was repelled at the Battle of Velletri. A number of reforms pertained to the church; the number of priests was limited to 10 for every 1000 inhabitants, later reduced to five; for the construction of new churches state permission was required, church tax reduced etc.; in 1741 and again in 1755 a concordat was signed. A Cadastral Survey of the kingdom was begun in 1740 and completed in the 1750s. A 1756 edict redefined the status of nobles, with the objective to turn them into a class of public servants. At the University of Naples Giambattista Vico (†1744), a critic of rationalist (enlightenment) philosophy, taught philosophy.

1759-1777

In 1759, King Charles inherited the Spanish crown; he abdicated as King of the Two Sicilies in favour of his son Ferdinand IV (later Ferdinand I) and, in the pragmatic decree of 1759, established rules for the succession in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, which was to be ruled by a side branch of the Spanish Bourbon Dynasty. From 1759 to 1777, minister Bernardo Tanucci, a Tuscan, dominated Neapolitan politics; he ruled as regent during the minority of Ferdinand IV (until 1767), and beyond since Ferdinand IV was not that interested in politics. Tanucci, who had served as minister under Charles, after 1759 reported on his actions to the court in Madrid; the Kingdom of Naples was no longer truly independent. The Kingdom of Naples, under Tanucci, implemented Bourbon Reforms, an early, concerted form of Enlightened Absolutism. The Jesuits were expelled in 1767; when Pope Clement XIII responded by excommunicating Tanucci, the latter ordered Pontecorvo and Benevento, exclaves of the Papal State surrounded by Neapolitan territory, occupied (until 1773). Steps were undertaken to make the Church of the Kingdom of Naples autonomous from Rome (Gallican style).

1777-1793

.jpg)

Ferdinand's wife Maria Carolina, a daughter of Austria's Maria Theresia, had Tanucci dismissed (1777) and replaced by Englishman John Acton; during his administration, the Two Sicilies switched from a Spanish dependence to an Anglo-Austrian alliance. Reform policy was continued, although at a reduced pace (termination of the inquisition 1782). Torture was not abolished until 1859. A Supreme Council of Finance was established in Naples in 1782. In 1778 the Neapolitan Academy of Science and Letters was founded. The Spanish and Austrian Line of the Habsburgs, the Spanish/Neapolitan Line of the Bourbon, the Dukes of Savoy, even minister Tanucci (a Tuscan) had one aspect in common : they were foreigners, and as such they were perceived by the establishment, the landowning nobility and the church, both of which cooperated in order to defend their position. The university of Naples was the first to appoint a professor for political economy, Antonio Genovesi (1754). Some attempts were made by the Neapolitan government to introduce reforms; the Jesuits were expelled in 1765, convents closed, attempts were made to reform the agriculture, vehemently opposed by the landowning nobility. In 1763/1764 Naples was struck by a severe famine.

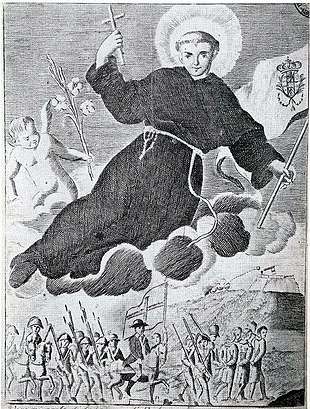

1793-1815

In 1793 the Kingdom of Two Sicilies joined the First War of the Coalition against France. Mount Vesuvius erupted in 1794. In 1798 Neapolitan forces moved into the Papal State in order to expel the French; the coalition falling apart, King Ferdinand, responding to Napoleon's threats, withdrew his forces. In 1799, a French force occupied Naples (i.e. the mainland part of the kingdom; king and administration had moved to Sicily) and proclaimed the short-lived Parthenopean. It faced armed resistance, in the organization of which the Catholic Church (Sanfedismo) played an important role; the French were labeled atheists and regicides. The French had to withdraw, and the Kingdom of Unified Naples regained her possessions on the mainland. In 1806 the French again invaded, Napoleon creating the Kingdom of Naples for his brother Joseph. King Ferdinand during the years 1806-1815 resided in Palermo on Sicily, his island kingdom being protected by the British fleet. In 1808, Joseph Bonaparte as King of Naples was replaced by Joachim Murat.

During the Hundred Days, Murat soon realized that the European powers, meeting at the Congress of Vienna, intended to remove him and return the Kingdom of Naples to its pre-Napoleonic rulers. Murat deserted his new allies before the War of the Seventh Coalition and, after issuing a proclamation to Italian patriots in Rimini, moved north to fight against the Austrians in the Neapolitan War in order to strengthen his rule in Italy by military means. However, he was defeated by Austrian general Frederick Bianchi at the Battle of Tolentino (2–3 May 1815).

History

1816-1848

The treaty of Casalanza restored Ferdinand IV of Bourbon back to the throne of Naples; the island of Sicily (where the constitution of 1812 virtually had disempowered him) was returned to him. He annulled the constitution in 1816; Sicily was fully reintegrated into what was now officially called the Regno delle Due Sicilie (Kingdom of Two Sicilies), Ferdinand IV became Ferdinand I.

A number of accomplishments under the administration of Kings Joseph and Joachim Murat, such as the Code Civil, the penal and commercial code, were kept (and extended to Sicily). In the mainland parts of the Kingdom, the power and influence of both nobility and clergy had been greatly reduced, however at the expense of law and order - brigandage and the forceful occupation of lands were problems the restored Kingdom inherited from their predecessor.

The Vienna Congress had granted Austria the right to station troops in the kingdom, and Austria, as well as Russia and Prussia, insisted that no written constitution was to be granted to the kingdom. In October 1815, Joachim Murat landed in Calabria, in an attempt to regain his kingdom; the government responded to acts of collaboration or of terrorism with severe repression; by June 1816 Murat's attempt had failed and the situation was under control. However, the Neapolitan administration had changed from conciliatory to reactionary. Henri de Stendhal, who visited Naples in 1817, called the kingdom "an absurd monarchy in the style of Philip II".

As open political activity was suppressed, liberals organized themselves in secret societies, such as the Carbonari, whose origins date back into the French period; the Carbonari organization had been outlawed in 1816; in 1820 a revolution planned by Carbonari and Carbonari supporters, aiming at the introduction of a written constitution (the Spanish constitution of 1812), did not unfold as planned. King Ferdinand still felt compelled to grant the constitution desired by the liberals (July 13th). A revolution erupted in Palermo, Sicily, that month, but was quickly suppressed. The Neapolitan rebels occupied Benevento and Pontecorvo, enclaves belonging to the Papal State. At the Congress of Troppau (Nov. 19th), the Holy Alliance (Metternich the driving force) decided to interfere. In view of 50,000 Austria troops, King Ferdinand (outside of his capital) cancelled the constitution February 23rd 1821; Neapolitan resistance (by regular forces under General Guglielmo Pepe, as well as by irregular rebel forces (Carbonari), against the Austrians was broken by force, on March 24th 1821 Austrian forces entered the city of Naples.

Political repression only intensified. To lawlessness in the countryside another problem intensified - corruption in the administration. An 1828 attempted coup to again force the promulgation of a constitution was suppressed by Neapolitan troops (the Austrian troops had left the previous year). King Francis I (1825-1830) died after having visited Paris, where he witnessed the 1830 revolution. In 1829 he had created the Royal Order of Merit (Royal Order of Francis I. of the Two Sicilies). His successor Ferdinand II. declared political amnesty and undertook steps to stimulate the economy, among them lowering the taxes. The railroad from Naples to Portici was taken in operation in 1839; progress was visible. However, the church still objected to the construction of tunnels, because of their 'obscenity'. The city of Naples received street lighting.

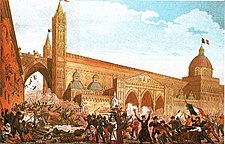

In 1836 the Kingdom was struck by a cholera epidemic which killed 65,000 in Sicily alone. In the following years the Neapolitan countryside saw sporadic local insurrections. In the 1840s, underground literature (political pamphlets etc.) evaded censorship; a September 1847 rising, before being suppressed, crossed from mainland Calabria over to Sicily. On January 13th 1848, an open rebellion began in Palermo; the reintroduction of the 1812 constitution was demanded. King Ferdinand appointed a liberal prime minister, broke diplomatic relations with Austria, even declared war on the latter (April 7th). While the revolutionaries in the mainland part of the kingdom (they had risen shortly after the Sicilians, in several cities except Naples) approved with these measures (April 1848), Sicily continued in her revolution. With the reformers on the mainland disagreeing, King Ferdinand, using the Swiss Guard, took the initiative and suppressed the revolution in Naples (May 15th); the mainland was again under royal control by July; in September 1848, Messina was taken. Palermo, the revolutionaries' capital and last stronghold, fell on May 15th 1849.

1848-1861

The Kingdom of Two Sicilies, in the course of 1848-1849, had been able to suppress the revolution and the attempt of Sicilian secession with their own forces, hired Swiss guards included. The war declared on Austria in April 1848, under pressure of public sentiment, had been an event on paper only.

_p1.034_-_IL_MARINAI_EPESCATORI.jpg)

In 1849 King Ferdinand II was 39 years old; he had begun as a reformer; the early death of his wife (1836), the frequency of political unrest, the extent and range of political expectations on the side of various groups that made up public opinion, had caused him to pursue a cautious, yet authoritarian policy aiming at the prevention of the occurrence of yet another rebellion. Over half of the delegates elected to parliament in the liberal atmosphere of 1848 were arrested or fled the country. The administration, in their treatment of political prisoners, in their observation of 'suspicious elements', violated the rights of the individual guaranteed by the constitution. Conditions were so bad that they caused international attention; in 1856 Britain and France demanded the release of the political prisoners. When this was rejected, both countries broke off diplomatic relations. The Kingdom pursued an economic policy of protectionism; the country's economy was mainly based on agriculture, the cities, especially Naples - with over 400,000 inhabitants Italy's largest - 'a center of consumption rather than of production' (Santore p.163) and home to poverty most expressed by the masses of Lazzaroni, the poorest class.

After visiting Naples in 1850, Gladstone began to support Neapolitan opponents of the Bourbon rulers: his "support" consistied of a couple of letters that he sent from Naples to the Parliament in London, describing the "awful conditions" of the Kingdom of Southern Italy and claiming that "it is the negation of God erected to a system of government". Gladstone's letters provoked sensitive reactions in the whole of Europe and helped to cause its diplomatic isolation prior to the invasion and annexation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies by the Kingdom of Sardinia, with the following foundation of modern Italy. Administratively, Naples and Sicily remained separate units; in 1858 the Neapolitan Postal Service issued her first postage stamps; that of Sicily followed in 1859.

.jpg)

Until 1849, the political movement among the bourgeoisie, at times revolutionary, had been Neapolitan respectively Sicilian rather than Italian in its tendency; Sicily in 1848-1849 had striven for a higher degree of independence from Naples rather than for a unified Italy. As public sentiment for Italian unification was rather low in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the country did not feature as an object of acquisition in the earlier plans of Piemont-Sardinia's prime minister Cavour. Only when Austria was defeated in 1859 and the unification of Northern Italy (except Venetia) was accomplished in 1860, did Giuseppe Garibaldi, at the head of his 1000 Redshirts, launch his invasion of Sicily, with the connivance of Cavour (Once in Sicily, many rallied to his colours); after a successful campaign in Sicily, he crossed over to the mainland and won the battle of the Volturno with half of his army being local volunteers. King Francis II (since 1859) withdrew to the fortified port of Gaeta, where he surrendered and abdicated in February 1861. At the encounter of Teano, Garibaldi met King Victor Emmanuel, transferring to him the conquered kingdom, the Two Sicilies were annexed into the Kingdom of Italy. What used to be the Kingdom of Two Sicilies became Italy's Mezzogiorno.

Arts patronage

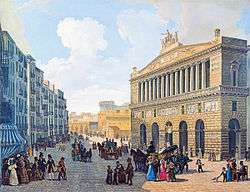

The Teatro Reale di San Carlo commissioned by the Bourbon King Charles VII of Naples who wanted to grant Naples a new and larger theatre to replace the old, dilapidated, and too-small Teatro San Bartolomeo of 1621. Which had served the city well, especially after Scarlatti had moved there in 1682 and had begun to create an important opera centre which existed well into the 1700s.[5] Thus, the San Carlo was inaugurated on 4 November 1737, the king's name day, with the performance of Domenico Sarro's opera Achille in Sciro and much admired for its architecture the San Carlo was now the biggest opera house in the world.[6]

On 13 February 1816[7] a fire broke out during a dress-rehearsal for a ballet performance and quickly spread to destroy a part of building. On the orders of King Ferdinand I, who used the services of Antonio Niccolini, to rebuild the opera house within ten months as a traditional horseshoe-shaped auditorium with 1,444 seats, and a proscenium, 33.5m wide and 30m high. The stage was 34.5m deep. Niccolini embellished in the inner of the bas-relief depicting "Time and the Hour". Stendhal attended the second night of the inauguration and wrote: "There is nothing in all Europe, I won’t say comparable to this theatre, but which gives the slightest idea of what it is like..., it dazzles the eyes, it enraptures the soul...".

From 1815 to 1822, Gioachino Rossini was the house composer and artistic director of the royal opera houses, including the San Carlo. During this period he wrote ten operas which were Elisabetta, regina d'Inghilterra (1815), La gazzetta, Otello, ossia il Moro di Venezia (1816), Armida (1817), Mosè in Egitto, Ricciardo e Zoraide (1818), Ermione, Bianca e Falliero, Eduardo e Cristina, La donna del lago (1819), Maometto II (1820), and Zelmira (1822), many premiered at the San Carlo. An offer in 1822 from Domenico Barbaja, the impresario of the San Carlo, which followed the composer's ninth opera, led to Gaetano Donizetti's move to Naples and his residency there which lasted until the production of Caterina Cornaro in January 1844.[8] In all, Naples presented 51 of Donizetti's operas.[8] Also Vincenzo Bellini's first professionally staged opera had its first performance at the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples on 30 May 1826.[9]

Historical population

| Year | Kingdom of Naples | Kingdom of Sicily | Total | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1819 | 5,733,430 | – |

– |

[10] |

| 1827 | – |

– |

~7,420,000 | [11] |

| 1828 | 6,177,598 | – |

– |

[10] |

| 1832 | – |

1,906,033 | – |

[10] |

| 1839 | 6,113,259 | – |

~8,000,000 | [10][12] |

| 1840 | 6,117,598 | ~<1,800,000 (est.) | 7,917,598 | [13] |

| 1848 | 6,382,706 | 2,046,610 | 8,429,316 | [12] |

| 1851 | 6,612,892 | 2,041,583 | 8,704,472 | [14] |

| 1856 | 6,886,030 | 2,231,020 | 9,117,050 | [15] |

| 1859/60 | 6,986,906 | 2,294,373 | 9,281,279 | [16] |

The kingdom had a large population, its capital Naples being the biggest city in Italy, at least three times as large as any other contemporary Italian state. At its peak, the kingdom had a military 100,000 soldiers strong, and a large bureaucracy.[17] Naples was the largest city in the kingdom and the third largest city in Europe. The second largest city, Palermo, was the third largest in Italy.[18] In the 1800s, the kingdom experienced large population growth, rising from approximately five to seven million.[19] It held approximately 36% of Italy's population around 1850.[20]

The population of the city of Naples numbered 427,000 in 1800, 449,000 in 1850 - an insignificant increase if compared to Milan, Turin, Paris. The numbers for Palermo were 139,000 in 1800, 180,000 in 1850. The population for the mainland part of the kingdom numbered 4.99 million around 1800, 4.91 million c. 1816, 5.6 million c. 1825, 5.93 million in 1833, 6.15 million in 1838. 6.38 million in 1845, 6.61 million in 1848, an increase of 32 % over half a decade. The population of Sicily had risen from 1.66 million c. 1800 to 2.10 million in 1848.

Because the kingdom did not establish a statistical department until after 1848,[21] most population statistics prior to that year are estimates and censuses undertaken were thought by contemporaries to be inaccurate.[10]

Economy

A major problem in the Kingdom was the distribution of land property - most of it concentrated in the hands of a few families, the Landed Oligarchy. The villages housed a large Rural Proletariat, desperately poor and dependent on the landlords for work. The Kingdom's few cities had little industry, thus not providing the outlet excess rural population found in northern Italy, France or Germany. The figures above show that the population of the countryside rose at a faster rate than that of the city of Naples herself, a rather odd phenomenon in a time when much of Europe experienced the Industrial Revolution.

Agriculture

.jpg)

As registered in the 1827[22] census, for the Neapolitan (continental) part of the kingdom, 1,475,314 of the male population were listed as Husbandmen which traditionally consisted of three classes the Borgesi (or yeomanry), the Inquilani (or small-farmers) and the Contadini (or peasantry), along with 65,225 listed as shepherds. Wheat, wine, olive oil and cotton were the chief products with an anual production, as recorded in 1844, of 67 mio. liters of olive oil greatly produced in Apulia and Calabria and loaded for export at Gallipoli along with 191 mio. liters of wine for the principal part home consumed. On the island of Sicily, in 1839, due to less arable lands, the output was much smaller than on the mainland yet ca.115,000 acres of Vineyards and ca.260,000 acres of Orchards, mainly fig, orange and citrus, were best cultivated.

Industry

Industry was the largest source of income if compared with the other preunitarian states. One of the most important industrial complexes in the kingdom was the shipyard of Castellammare di Stabia, which employed 1800 workers. The engineering factory of Pietrarsa was the largest industrial plant in the Italian peninsula, producing tools, cannons, rails, locomotives. The complex also included a school for train drivers, and naval engineers and, thanks to this school, the kingdom was able to replace the English personnel who had been necessary until then. The first steamboat with screw propulsion known in the Mediterranean Sea was the "Giglio delle Onde", with mail delivery and passenger transport purposes after 1847.

In Calabria, the Fonderia Ferdinandea was a large foundry where cast iron was produced. The Reali ferriere ed Officine di Mongiana was an iron foundry and weapons factory. Founded in 1770, it employed 1600 workers in 1860 and closed in 1880. In Sicily (near Catania and Agrigento), sulfur was mined to make gunpowder. The Sicilian mines were able to satisfy most of the global demand for sulfur. Silk cloth production was focused in San Leucio (near Caserta). The region of Basilicata also had several mills in Potenza and San Chirico Raparo, where cotton, wool and silk were processed. Food processing was widespread, especially near Naples (Torre Annunziata and Gragnano).

Sulfur

The kingdom maintained a large sulfur mining industry. In industrializing Britain, with the repeal of tariffs on salt in 1824, demand for sulfur from Sicily surged upward. The increasing British control and exploitation of the mining, refining, and transportation of the sulfur, coupled with the failure of this lucrative export to transform Sicily's backward and impoverished economy, led to the 'Sulfur Crisis' of 1840, when King Ferdinand II gave a monopoly of the sulfur industry to a French firm, violating an earlier 1816 trade agreement with Britain. A peaceful solution was eventually negotiated by France.[23][24]

Transport

With all of its major cities boasting successful ports, transport and trade in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was most efficiently conducted by sea. The Kingdom possessed the largest merchant fleet in the Mediterranean. Urban road conditions were to the best European standards, by 1839, the main streets of Naples were gas-lit. Efforts were made to tackle the tough mountainous terrain, Ferdinand II built the cliff-top road along the Sorrentine peninsula. Road conditions in the interior and hinterland areas of the kingdom made internal trade difficult. The first railways and iron-suspension bridges in Italy were developed in the south, as was the first overland electric telegraph cable.

Technological and scientific achievements

The kingdom achieved several scientific and technological accomplishments, such as the first steamboat in the Mediterrean Sea (1818),[25][26] built in the shipyard of Stanislao Filosa al ponte di Vigliena, near Naples, and the first railway in the Italian peninsula (1839), which connected Naples to Portici.[27] However, until the Italian unification, the railway development was highly limited. In the year 1859, the kingdom had only 99 kilometers of rail, compared to the 850 kilometers of Piedmont.[28] This was because the kingdom could count on a very large and efficient merchant navy, which was able to compensate for the need for railways. Also, southern landscape was mainly mountainous making the process of building railways quite difficult, as building railway tunnels was much harder at the time. Other achievements included the first volcano observatory in the world, l'Osservatorio Vesuviano (1841),[29][30]. The rails for the first Italian railways were built in Mongiana as well. All the rails of the old railways that went from the south to as far as Bologna were built in Mongiana.

Education

Naples was home to a University and, established by Matteo Ripa in 1732, the oldest school in Europe teaching Sinology and Oriental studies while a further two universities operated in Sicily. Despite these institutions of higher learning the kingdom had no obligations for school attendance nor a recognizable school system. Clerics could inspect schools and had veto power over appointments of teachers, who were mostly part of the clergy anyhow. The Literacy rate was just 14.4% in 1861.

Geography

Departments

The peninsula was divided into fifteen departments[31][32] and Sicily was divided into seven departments.[33] The island itself had a special administrative status, with its base at Palermo. In 1860, when the Two Sicilies were conquered by the Kingdom of Sardinia, the departments became provinces of Italy, according to the Rattazzi law.

Peninsula departments

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Insular departments

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- The city of Benevento was formally included in this department, but it was occupied by the Papal States and was de facto an exclave of that country.

Monarchy

Kings of the Two Sicilies

Ferdinand I, 1816–1825

Ferdinand I, 1816–1825 Francis I, 1825–1830

Francis I, 1825–1830 Ferdinand II, 1830–1859

Ferdinand II, 1830–1859 Francis II, 1859–1861

Francis II, 1859–1861

In 1860–61 with influence from Great Britain and Gladstone's propaganda, the kingdom was absorbed into the Kingdom of Sardinia, and the title dropped. It is still claimed by the head of the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies.

Titles of King of the Two Sicilies

Francis I or Francis II, King of the Two Sicilies, of Jerusalem, etc., Duke of Parma, Piacenza, Castro, etc., Hereditary Grand Prince of Tuscany, etc.[34]

House of Bourbon in exile

Some sovereigns continued to maintain diplomatic relations with the exiled court, including the Emperor of Austria, the Kings of Bavaria, Württemberg and Hanover, the Queen of Spain, the Emperor of Russia, and the Papacy.

Flags of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

.svg.png) 1816–1848; 1849–1860 flag

1816–1848; 1849–1860 flag.svg.png) 1848–1849 flag

1848–1849 flag.svg.png) 1860–1861 flag

1860–1861 flag Framed antique flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (c. 1830s) discovered in Palermo.

Framed antique flag of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (c. 1830s) discovered in Palermo.

Orders of knighthood

- Order of St. Januarius

- Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George

- Order of Saint George and Reunion

- Order of Saint Ferdinand and Merit

- Royal Order of Francis I

Further reading

- The Volcano Lover, a novel by Susan Sontag, is set in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies during the Napoleonic era.

See also

References

- Swinburne, Henry (1790). Travels in the Two Sicilies (1790). British Library.

two sicilies.

- De Sangro, Michele (2003). I Borboni nel Regno delle Due Sicilie (in Italian). Lecce: Edizioni Caponi.

- Nicola Zitara. "La legge di Archimede: L'accumulazione selvaggia nell'Italia unificata e la nascita del colonialismo interno" (PDF) (in Italian). Eleaml-Fora!.

- "Sicilian History". Dieli.net. 7 October 2007.

- Lynn 2005, p. 277

- Beauvert 1985, p. 44

- Gubler 2012, p. 55

- Black 1982, p. 1

- Weinstock 1971, pp. 30—34

- Macgregor, John (1850). Commercial Statistics: A Digest of the Productive Resources, Commercial Legislation, Customs Tariffs, of All Nations. Including All British Commercial Treaties with Foreign States. Whittaker and Company. pp. 18.

- partington, charles F. (1836). The british cyclopedia of literature, history,geography, law ,and politics. p. 553.

- Berkeley, G. F.-H.; Berkeley, George Fitz-Hardinge; Berkeley, Joan (1968). Italy in the Making 1815 to 1846. Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-07427-8.

- Commercial Statistics: A Digest of the Productive Resources, Commercial Legislation, Customs Tariffs ... of All Nations ... C. Knight and Company. 1844. p. 18.

- The Popular Encyclopedia: Or, Conversations Lexicon. Blackie. 1862. p. 246.

- Russell, John (1870). Selections from Speeches of Earl Russell 1817 to 1841 and from Despatches 1859 to 1865: With Introductions. In 2 Volumes. Longmans, Green, and Company. p. 223.

- Mezzogiorno d'Europa. 1983. p. 473.

- Ziblatt, Daniel (21 January 2008). Structuring the State: The Formation of Italy and Germany and the Puzzle of Federalism. Princeton University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-4008-2724-4.

- Hearder, Harry (22 July 2014). Italy in the Age of the Risorgimento 1790 - 1870. Routledge. pp. 125–6. ISBN 978-1-317-87206-1.

- Astarita, Tommaso (17 July 2006). Between Salt Water and Holy Water: A History of Southern Italy. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-25432-7.

kingdom of the two sicilies population.

- Toniolo, Gianni (14 October 2014). An Economic History of Liberal Italy (Routledge Revivals): 1850-1918. Routledge. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-317-56953-4.

- House Documents. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1870. p. 19.

- MacGregor, John (1844). Commercial Statistics Vol.I. London.

- Thomson, D. W. (April 1995). "Prelude to the Sulphur War of 1840: The Neapolitan Perspective". European History Quarterly. 25 (2): 163–180. doi:10.1177/026569149502500201.

- Riall, Lucy (1998). Sicily and the Unification of Italy: Liberal Policy and Local Power, 1859–1866. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191542619. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- The Economist. Economist Newspaper Limited. 1975.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (12 October 2012). Naval Warfare, 1815-1914. Routledge. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-134-60994-9.

- "La Dolce Vita? Italy By Rail, 1839-1914 | History Today". History Today. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Duggan, Christopher (1994). A Concise History of Italy. Cambridge University Press. pp. 152. ISBN 978-0-521-40848-6.

- De Lucia, Maddalena; Ottaiano, Mena; Limoncelli, Bianca; Parlato, Luigi; Scala, Omar; Siviglia, Vittoria (2010). "The Museum of Vesuvius Observatory and its public. Years 2005 - 2008". EGUGA: 2942. Bibcode:2010EGUGA..12.2942D.

- Klemetti, Erik (7 June 2009). "Volcano Profile: Mt. Vesuvius". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Goodwin, John (1842). "Progress of the Two Sicilies Under the Spanish Bourbons, from the Year 1734-35 to 1840". Journal of the Statistical Society of London. 5 (1): 47–73. doi:10.2307/2337950. ISSN 0959-5341. JSTOR 2337950.

- Pompilio Petitti (1851). Repertorio amministrativo ossia collezione di leggi, decreti, reali rescritti ecc. sull'amministrazione civile del Regno delle Due Sicilie, vol. 1 (in Italian). Napoli: Stabilimento Migliaccio. p. 1.

- Pompilio Petitti (1851). Repertorio amministrativo ossia collezione di leggi, decreti, reali rescritti ecc. sull'amministrazione civile del Regno delle Due Sicilie, vol. 1 (in Italian). Napoli: Stabilimento Migliaccio. p. 4.

- States, United (1931). Treaties and Other International Acts of the United States of America: Documents 173-200: 1855-1858. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 250.

Further reading

- Alio, Jacqueline. Sicilian Studies: A Guide and Syllabus for Educators (2018), 250 pp.

- Eckaus, Richard S. "The North-South differential in Italian economic development." Journal of Economic History (1961) 21#3 pp: 285–317.

- Finley, M. I., Denis Mack Smith and Christopher Duggan, A History of Sicily (1987) abridged one-volume version of 3-volume set of 1969)

- Imbruglia, Girolamo, ed. Naples in the eighteenth century: The birth and death of a nation state (Cambridge University Press, 2000)

- Petrusewicz, Marta. "Before the Southern Question: 'Native' Ideas on Backwardness and Remedies in the Kingdom of Two Sicilies, 1815–1849." in Italy's 'Southern Question' (Oxford: Berg, 1998) pp: 27–50.

- Pinto, Carmine. "The 1860 disciplined Revolution. The Collapse of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies." Contemporanea (2013) 16#1 pp: 39–68.

- Riall, Lucy. Sicily and the Unification of Italy: Liberal Policy & Local Power, 1859–1866 (1998), 252pp

- Zamagni, Vera. The economic history of Italy 1860–1990 (Oxford University Press, 1993)

External links

- (in Italian) Brigantino – Il portale del Sud, a massive Italian-language site dedicated to the history, culture and arts of southern Italy

- (in Italian) Casa Editoriale Il Giglio, an Italian publisher that focuses on history, culture and the arts in the Two Sicilies

- (in Italian) La Voce di Megaride, a website by Marina Salvadore dedicated to Napoli and Southern Italy

- (in Italian) Associazione culturale "Amici di Angelo Manna", dedicated to the work of Angelo Manna, historian, poet and deputy

- (in Italian) Fora! The e-journal of Nicola Zitara, professor; includes many articles about southern Italy's culture and history

- Regalis, a website on Italian dynastic history, with sections on the House of the Two Sicilies

.jpg)