History of the Philippines (1898–1946)

The history of the Philippines from 1898 to 1946 describes the period of the American colonization of the Philippines. It began with the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in April 1898, when the Philippines was still a colony of the Spanish East Indies, and concluded when the United States formally recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines on July 4, 1946.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the United States |

|

|

By ethnicity |

|

|

With the signing of the Treaty of Paris on December 10, 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States, thereby beginning the era of American colonization.[1] The interim U.S. military government of the Philippine Islands experienced a period of great political turbulence, characterised by the Philippine–American War.

Beginning in 1901, the military government was replaced by a civilian government—the Insular Government of the Philippine Islands—with William Howard Taft serving as its first Governor-General. Also, a series of insurgent governments that lacked significant international and diplomatic recognition existed between 1898 and 1904.[lower-alpha 1]

Following the passage of the Philippine Independence Act in 1934, a Philippine presidential election was held in 1935. Manuel L. Quezon was elected and inaugurated second President of the Philippines on November 15, 1935. The Insular Government was dissolved and the Commonwealth of the Philippines, intended to be a transitional government in preparation for the country's full achievement of independence in 1946, was brought into existence.[2]

After the World War II Japanese invasion in 1941 and subsequent occupation of the Philippines, the United States and Philippine Commonwealth military recaptured the Philippines in 1945. The United States formally recognised the independence of the Republic of the Philippines on July 4, 1946, according to the terms of the Philippine Independence Act.[2]

Historical perspective

.jpg)

The Philippine Revolution began in August 1896 and ended with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato, a ceasefire between the Spanish colonial Governor-General Fernando Primo de Rivera and the revolutionary leader Emilio Aguinaldo which was signed on December 15, 1897. The terms of the pact called for Aguinaldo and his militia to surrender. Other revolutionary leaders were given amnesty and a monetary indemnity by the Spanish government in return for which the rebel government agreed to go into exile in Hong Kong.[3][4][5]

Spanish–American War (1898)

The failure of Spain to engage in active social reforms in Cuba as demanded by the United States government was the basic cause for the Spanish–American War. American attention was focused on the issue after the mysterious explosion that sank the American battleship Maine on February 15, 1898 in Havana Harbor. As public political pressure from the Democratic Party and certain industrialists built up for war, the U.S. Congress forced the reluctant Republican President William McKinley to issue an ultimatum to Spain on April 19, 1898. Spain found it had no diplomatic support in Europe, but nevertheless declared war; the U.S. followed on April 25 with its own declaration of war.[6][7]

Theodore Roosevelt, who was at that time Assistant Secretary of the Navy, ordered Commodore George Dewey, commanding the Asiatic Squadron of the United States Navy: "Order the squadron ...to Hong Kong. Keep full of coal. In the event of declaration of war Spain, your duty will be to see that the Spanish squadron does not leave the Asiatic coast, and then offensive operations in Philippine Islands." Dewey's squadron departed on April 27 for the Philippines, reaching Manila Bay on the evening of April 30.[8]

Battle of Manila Bay

The Battle of Manila Bay took place on May 1, 1898. In a matter of hours, Commodore Dewey's Asiatic Squadron defeated the Spanish squadron under Admiral Patricio Montojo.[9][10] The U.S. squadron took control of the arsenal and navy yard at Cavite. Dewey cabled Washington, stating that although he controlled Manila Bay, he needed 5,000 additional men to seize Manila itself.[9]

U.S. preparation for land-based operations

The unexpected rapidity and completeness of Dewey's victory in the first engagement of the war prompted the McKinley administration to make the decision to capture Manila from the Spanish. The United States Army began to assemble the Eighth Army Corps—a military unit which would consist of 10,844 soldiers under the command of Major General Wesley Merritt—in preparation for deployment to the Philippines.[9]

While awaiting the arrival of troops from the Eighth Corps, Dewey dispatched the cutter USRC McCulloch to Hong Kong to transport Aguinaldo back to the Philippines.

Aguinaldo arrived on May 19 and, after a brief meeting with Dewey, resumed revolutionary activities against the Spanish. On May 24, Aguinaldo issued a proclamation in which he assumed command of all Philippine forces and announced his intention to establish a dictatorial government with himself as dictator, saying that he would resign in favor of a duly elected president.[11]

Public jubilation marked Aguinaldo's return. Many Filipino enlisted men deserted local Spanish army units to join Aguinaldo's command and the Philippine Revolution against Spain resumed. Soon, many cities such as Imus, Bacoor, Parañaque, Las Piñas, Morong, Macabebe and San Fernando, as well as some entire provinces such as Laguna, Batangas, Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, Bataan, Tayabas (now Quezon), and the Camarines provinces, were liberated by the Filipinos and the port of Dalahican in Cavite was secured.[12]

The first contingent of American troops arrived on June 30 under the command of Brigadier General Thomas McArthur Anderson, commander of the Eighth Corps' 2nd Division (U.S. brigade and division numbers of the era were not unique throughout the army). General Anderson wrote to Aguinaldo, requesting his cooperation in military operations against the Spanish forces.[13] Aguinaldo responded, thanking General Anderson for his amicable sentiments, but saying nothing about military cooperation. General Anderson did not renew the request.[13]

The 2nd Brigade and the 2nd Division of the Eighth Corps arrived on July 17, under the command of Brigadier General Francis V. Greene. Major General Merritt (the Commander in Chief of the Philippine Expedition) and his staff arrived at Cavite on July 25. The 1st Brigade of the corps' 2nd Division arrived on July 30, under the command of Brigadier General Arthur MacArthur.[14]

Philippine declaration of independence

On June 12, 1898, Aguinaldo proclaimed the independence of the Philippines at his house in Cavite El Viejo.[15][16] Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista wrote the Philippine Declaration of Independence, and read this document in Spanish that day at Aguinaldo's house.[17] On June 18, Aguinaldo issued a decree formally establishing his dictatorial government.[18] On June 23, Aguinaldo issued another decree, this time replacing the dictatorial government with a revolutionary government (and naming himself as President).[19][20]

Writing retrospectively in 1899, Aguinaldo claimed that an American naval officer had urged him to return to the Philippines to fight the Spanish and said "The United States is a great and rich nation and needs no colonies."[21] Aguinaldo also wrote that after checking with Dewey by telegraph, U.S. Consul E. Spencer Pratt had assured him in Singapore:

That the United States would at least recognize the independence of the Philippines under the protection of the United States Navy. The consul added that there was no necessity for entering into a formal written agreement because the word of the Admiral and of the United States Consul were in fact equivalent to the most solemn pledge that their verbal promises and assurance would be fulfilled to the letter and were not to be classed with Spanish promises or Spanish ideas of a man’s word of honour.[21]

Aguinaldo received nothing in writing.

On April 28 Pratt wrote to United States Secretary of State William R. Day, explaining the details of his meeting with Aguinaldo:

At this interview, after learning from General Aguinaldo the state of an object sought to be obtained by the present insurrectionary movement, which, though absent from the Philippines, he was still directing, I took it upon myself, whilst explaining that I had no authority to speak for the Government, to point out the danger of continuing independent action at this stage; and, having convinced him of the expediency of cooperating with our fleet, then at Hongkong, and obtained the assurance of his willingness to proceed thither and confer with Commodore Dewey to that end, should the latter so desire, I telegraphed the Commodore the same day as follows, through our consul-general at Hongkong:--[22]

There was no mention in the cablegrams between Pratt and Dewey of independence or indeed of any conditions on which Aguinaldo was to cooperate, these details being left for future arrangement with Dewey. Pratt had intended to facilitate the occupation and administration of the Philippines, and also to prevent a possible conflict of action. In a communication written on July 28, Pratt made the following statement:

I declined even to discuss with General Aguinaldo the question of the future policy of the United States with regard to the Philippines, that I held out no hopes to him of any kind, committed the government in no way whatever, and, in the course of our confidences, never acted upon the assumption that the Government would cooperate with him—General Aguinaldo—for the furtherance of any plans of his own, nor that, in accepting his said cooperation, it would consider itself pledged to recognize any political claims which he might put forward.[23]

On June 16, Secretary Day cabled Consul Pratt: "Avoid unauthorized negotiations with the Philippine insurgents," and later on the same day:[24]

The Department observes that you informed General Aguinaldo that you had no authority to speak for the United States; and, in the absence of the fuller report which you promise, it is assumed that you did not attempt to commit this Government to any alliance with the Philippine insurgents. To obtain the unconditional personal assistance of General Aguinaldo in the expedition to Manila was proper, if in so doing he was not induced to form hopes which it might not be practicable to gratify. This Government has known the Philippine insurgents only as discontented and rebellious subjects of Spain, and is not acquainted with their purposes. While their contest with that power has been a matter of public notoriety, they have neither asked nor received from this Government any recognition. The United States, in entering upon the occupation of the islands, as the result of its military operations in that quarter, will do so in the exercise of the rights which the state of war confers, and will expect from the inhabitants, without regard to their former attitude toward the Spanish Government, that obedience which will be lawfully due from them.

If, in the course of your conferences with General Aguinaldo, you acted upon the assumption that this Government would co-operate with him for the furtherance of any plan of his own, or that, in accepting his co-operation, it would consider itself pledged to recognize any political claims which he may put forward, your action was unauthorized and can not be approved.

Filipino scholar Maximo Kalaw wrote in 1927: "A few of the principal facts, however, seem quite clear. Aguinaldo was not made to understand that, in consideration of Filipino cooperation, the United States would extend its sovereignty over the Islands, and thus in place of the old Spanish master a new one would step in. The truth was that nobody at the time ever thought that the end of the war would result in the retention of the Philippines by the United States."[25]

Tensions between U.S. and revolutionary forces

On July 9 General Anderson informed Major General Henry Clark Corbin, the Adjutant General of the U.S. Army, that Aguinaldo "has declared himself Dictator and President, and is trying to take Manila without our assistance", opining that that would not be probable but, if done, would allow him to antagonize any U.S. attempt to establish a provisional government.[26] On July 15, Aguinaldo issued three organic decrees assuming civil authority of the Philippines.[27]

On July 18, General Anderson wrote that he suspected Aguinaldo to be secretly negotiating with the Spanish authorities.[26] In a July 21 letter to the Adjutant General, General Anderson wrote that Aguinaldo had "put in operation an elaborate system of military government, under his assumed authority as Dictator, and has prohibited any supplies being given us, except by his order," and that Anderson had written to Aguinaldo that the requisitions on the country for necessary items must be filled, and that he must aid in having them filled.[28]

On July 24, Aguinaldo wrote a letter to General Anderson in effect warning him not to disembark American troops in places conquered by the Filipinos from the Spaniards without first communicating in writing the places to be occupied and the object of the occupation. Murat Halstead, official historian of the Philippine Expedition, writes that General Merritt remarked shortly after his arrival on June 25,

As General Aguinaldo did not visit me on my arrival, nor offer his services as a subordinate military leader, and as my instructions from the President fully contemplated the occupation of the islands by the American land forces, and stated that 'the powers of the military occupant are absolute and supreme and immediately operate upon the political condition of the inhabitants,' I did not consider it wise to hold any direct communication with the insurgent leader until I should be in possession of the city of Manila, especially as I would not until then be in a position to issue a proclamation and enforce my authority, in the event that his pretensions should clash with my designs.[29]

U.S. commanders suspected that Aguinaldo and his forces were informing the Spanish of American movements. U.S. Army Major John R. M. Taylor later wrote, after translating and analyzing insurgent documents,

The officers of the United States Army who believed that the insurgents were informing the Spaniards of the American movements were right. Sastrón has printed a letter from Pío del Pilar, dated July 30, to the Spanish officer commanding at Santa Ana, in which Pilar said that Aguinaldo had told him that the Americans would attack the Spanish lines on August 2 and advised that the Spaniards should not give way, but hold their positions. Pilar added, however, that if the Spaniards should fall back on the walled city and surrender Santa Ana to himself, he would hold it with his own men. Aguinaldo's information was correct, and on August 2 eight American soldiers were killed or wounded by the Spanish fire.[30]

On the evening of August 12, on orders of General Merritt, General Anderson notified Aguinaldo to forbid the insurgents under his command from entering Manila. On August 13, unaware of the peace protocol signing, U.S. forces assaulted and captured the Spanish positions in Manila. Insurgents made an independent attack of their own, as planned, which promptly led to trouble with the Americans. At 0800 that morning, Aguinaldo received a telegram from General Anderson, sternly warning him not to let his troops enter Manila without the consent of the American commander, who was situated on the south side of the Pasig River. General Anderson's request was ignored, and Aguinaldo's forces crowded forward alongside the American forces until they directly confronted the Spanish troops. Although the Spanish were waving a flag of truce, the insurgents fired on the Spanish forces, provoking return fire. 19 American soldiers were killed, and 103 more were wounded in this action.[31][32]

General Anderson sent Aguinaldo a telegram, later that day, which read:

Dated Ermita Headquarters 2nd Division 13 to Gen. Aguinaldo. Commanding Filipino Forces.--Manila, taken. Serious trouble threatened between our forces. Try and prevent it. Your troops should not force themselves in the city until we have received the full surrender then we will negotiate with you. -Anderson, commanding.

Aguinaldo however demanded joint occupation of Manila. On August 13 Admiral Dewey and General Merritt informed their superiors of this and asked how far they might proceed in enforcing obedience in the matter.[33]

General Merritt received news of the August 12 peace protocol on August 16, three days after the surrender of Manila.[34] Admiral Dewey and General Merritt were informed by a telegram dated August 17 that the President of the United States had directed:

That there must be no joint occupation with the Insurgents. The United States in the possession of Manila city, Manila bay and harbor must preserve the peace and protect persons and property within the territory occupied by their military and naval forces. The insurgents and all others must recognize the military occupation and authority of the United States and the cessation of hostilities proclaimed by the President. Use whatever means in your judgment are necessary to this end.[33]

Insurgent forces were looting the portions of the city which they occupied, and were not confining their attacks to Spaniards, but were assaulting their own people and raiding the property of foreigners as well. U.S. commanders pressed Aguinaldo to withdraw his forces from Manila. Negotiations proceeded slowly and, on August 31, General Elwell Otis (General Merritt being unavailable) wrote, in a long letter to Aguinaldo:

... I am compelled by my instructions to direct that your armed forces evacuate the entire city of Manila, including its suburbs and defences, and that I shall be obliged to take action with that end in view within a very short space of time should you decline to comply with my Government's demands; and I hereby serve notice on you that unless your troops are withdrawn beyond the line of the city's defences before Thursday, the 15th instant, I shall be obliged to resort to forcible action, and that my Government will hold you responsible for any unfortunate consequences which may ensue.[35]

After further negotiation and exchanges of letters, Aguinaldo wrote on September 16: "On the evening of the 15th the armed insurgent organizations withdrew from the city and all of its suburbs, ...[36]

Peace protocol between the U.S. and Spain

On August 12, 1898, The New York Times reported that a peace protocol had been signed in Washington that afternoon between the U.S. and Spain, suspending hostilities between the two nations.[37] The full text of the protocol was not made public until November 5, but Article III read: "The United States will occupy and hold the City, Bay, and Harbor of Manila, pending the conclusion of a treaty of peace, which shall determine the control, disposition, and government of the Philippines."[38][39] After conclusion of this agreement, U.S. President McKinley proclaimed a suspension of hostilities with Spain.[40]

Capture of Manila

By June, U.S. and Filipino forces had taken control of most of the islands, except for the walled city of Intramuros. Admiral Dewey and General Merritt were able to work out a bloodless solution with acting Governor-General Fermín Jáudenes. The negotiating parties made a secret agreement to stage a mock battle in which the Spanish forces would be defeated by the American forces, but the Filipino forces would not be allowed to enter the city. This plan minimized the risk of unnecessary casualties on all sides, while the Spanish would also avoid the shame of possibly having to surrender Intramuros to the Filipino forces.[41] On the eve of the mock battle, General Anderson telegraphed Aguinaldo, "Do not let your troops enter Manila without the permission of the American commander. On this side of the Pasig River you will be under fire".[42]

On August 13, with American commanders unaware that a ceasefire had already been signed between Spain and the U.S. on the previous day, American forces captured the city of Manila from the Spanish in the Battle of Manila.[43][44][45] The battle started when Dewey's ships bombarded Fort San Antonio Abad, a decrepit structure on the southern outskirts of Manila, and the virtually impregnable walls of Intramuros. In accordance with the plan, the Spanish forces withdrew while U.S. forces advanced. Once a sufficient show of battle had been made, Dewey hoisted the signal "D.W.H.B." (meaning "Do you surrender?),[46] whereupon the Spanish hoisted a white flag and Manila was formally surrendered to U.S. forces.[47]

This battle marked the end of Filipino-American collaboration, as the American action of preventing Filipino forces from entering the captured city of Manila was deeply resented by the Filipinos. This later led to the Philippine–American War,[48] which would prove to be more deadly and costly than the Spanish–American War.

U.S. military government

On August 14, 1898, two days after the capture of Manila, the U.S. established a military government in the Philippines, with General Merritt acting as military governor.[49] During military rule (1898–1902), the U.S. military commander governed the Philippines under the authority of the U.S. president as Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces. After the appointment of a civil Governor-General, the procedure developed that as parts of the country were pacified and placed firmly under American control, responsibility for the area would be passed to the civilian.

General Merritt was succeeded by General Otis as military governor, who in turn was succeeded by General MacArthur. Major General Adna Chaffee was the final military governor. The position of military governor was abolished in July 1902, after which the civil Governor-General became the sole executive authority in the Philippines.[50][51]

Under the military government, an American-style school system was introduced, initially with soldiers as teachers; civil and criminal courts were reestablished, including a supreme court;[52] and local governments were established in towns and provinces. The first local election was conducted by General Harold W. Lawton on May 7, 1899, in Baliuag, Bulacan.[53]

U.S. and insurgents clash

In a clash at Cavite between United States soldiers and insurgents on August 25, 1898, George Hudson of the Utah regiment was killed, Corporal William Anderson was mortally wounded, and four troopers of the Fourth Cavalry were slightly wounded.[54][55] This provoked General Anderson to send Aguinaldo a letter saying, "In order to avoid the very serious misfortune of an encounter between our troops, I demand your immediate withdrawal with your guard from Cavite. One of my men has been killed and three wounded by your people. This is positive and does not admit of explanation or delay."[55] Internal insurgent communications reported that the Americans were drunk at the time. Halstead writes that Aguinaldo expressed his regret and promised to punish the offenders.[54] In internal insurgent communications, Apolinario Mabini initially proposed to investigate and punish any offenders identified. Aguinaldo modified this, ordering, "... say that he was not killed by your soldiers, but by them themselves [the Americans] since they were drunk according to your telegram".[56] An insurgent officer in Cavite at the time reported on his record of services that he: "took part in the movement against the Americans on the afternoon of the 24th of August, under the orders of the commander of the troops and the adjutant of the post."[57]

Philippine elections, Malolos Congress, Constitutional government

Elections were held by the Revolutionary Government between June and September 10, resulting in Emilio Aguinaldo being seated as President in the seating of a legislature known as the Malolos Congress. In a session between September 15 and November 13, 1898, the Malolos Constitution was adopted. It was promulgated on January 21, 1899, creating the First Philippine Republic.[58]

Spanish–American War ends

Article V of the peace protocol signed on August 12 had mandated negotiations to conclude a treaty of peace to begin in Paris not later than October 1, 1898.[59] President McKinley sent a five-man commission, initially instructed to demand no more than Luzon, Guam, and Puerto Rico; which would have provided a limited U.S. empire of pinpoint colonies to support a global fleet and provide communication links.[60] In Paris, the commission was besieged with advice, particularly from American generals and European diplomats, to demand the entire Philippine archipelago.[60] The unanimous recommendation was that "it would certainly be cheaper and more humane to take the entire Philippines than to keep only part of it."[61] On October 28, 1898, McKinley wired the commission that "cessation of Luzon alone, leaving the rest of the islands subject to Spanish rule, or to be the subject of future contention, cannot be justified on political, commercial, or humanitarian grounds. The cessation must be the whole archipeligo or none. The latter is wholly inadmissible, and the former must therefore be required."[62] The Spanish negotiators were furious over the "immodist demands of a conqueror", but their wounded pride was assuaged by an offer of twenty million dollars for "Spanish improvements" to the islands. The Spaniards capitulated, and on December 10, 1898, the U.S. and Spain signed the Treaty of Paris, formally ending the Spanish–American War. In Article III, Spain ceded the Philippine archipelago to the United States, as follows: "Spain cedes to the United States the archipelago known as the Philippine Islands, and comprehending the islands lying within the following line: [... geographic description elided ...]. The United States will pay to Spain the sum of twenty million dollars ($20,000,000) within three months after the exchange of the ratifications of the present treaty."[63]

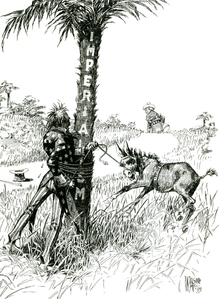

In the U.S., there was a movement for Philippine independence; some said that the U.S. had no right to a land where many of the people wanted self-government. In 1898 Andrew Carnegie, an industrialist and steel magnate, offered to pay the U.S. government $20 million to give the Philippines its independence.[64]

On November 7, 1900, Spain and the U.S. signed the Treaty of Washington, clarifying that the territories relinquished by Spain to the United States included any and all islands belonging to the Philippine Archipelago, but lying outside the lines described in the Treaty of Paris. That treaty explicitly named the islands of Cagayan Sulu and Sibutu and their dependencies as among the relinquished territories.[65]

Benevolent assimilation

U.S. President McKinley's December 21, 1898 proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation was announced in the Philippines on January 4, 1899. Referring to the Treaty of Paris, it said that as a result of the victories of American arms, the future control, disposition, and government of the Philippine Islands are ceded to the United States. It enjoined the military commander (General Otis) to make known to the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands that in succeeding to the sovereignty of Spain, the authority of the United States is to be exerted for the securing of the persons and property of the people of the islands and for the confirmation of all their private rights and relations. It specified that it will be the duty of the commander of the forces of occupation to announce and proclaim in the most public manner that we come, not as invaders or conquerors, but as friends, to protect the natives in their homes, in their employments, and in their personal and religious rights.[66] On January 6, 1899, General Otis was quoted in The New York Times as expressing himself as convinced that the U.S. government intends to seek the establishment of a liberal government, in which the people will be as fully represented as the maintenance of law and order will permit, susceptible of development, on lines of increased representation, and the bestowal of increased powers, into a government as free and independent as is enjoyed by the most favored provinces in the world.[67]

Philippine–American War (1899–1902)

Tensions escalate

The Spanish had yielded Iloilo to the insurgents in 1898 for the purpose of troubling the Americans. On January 1, 1899, news had come to Washington from Manila that American forces which had been sent to Iloilo under the command of General Marcus Miller had been confronted by 6,000 armed Filipinos, who refused them permission to land.[68][69] A Filipino official styling himself "Presidente Lopez of the Federal Government of the Visayas" informed Miller that "foreign troops" would not land "without express orders from the central government of Luzon".[69] On December 21, 1898, President McKinley issued a Proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation. General Otis delayed its publication until January 4, 1899, then publishing an amended version edited so as not to convey the meanings of the terms "sovereignty", "protection", and "right of cessation" which were present in the unabridged version.[70] Unknown to Otis, the War Department had also sent an enciphered copy of the Benevolent Assimilation proclamation to General Marcus Miller in Iloilo for informational purposes. Miller assumed that it was for distribution and, unaware that a politically bowdlerized version had been sent to Aguinaldo, published it in both Spanish and Tagalog translations which eventually made their way to Aguinaldo.[71] Even before Aguinaldo received the unaltered version and observed the changes in the copy he had received from Otis, he was upset that Otis had altered his own title to "Military Governor of the Philippines" from "... in the Philippines". Aguinaldo did not miss the significance of the alteration, which Otis had made without authorization from Washington.[72]

On January 5, Aguinaldo issued a counter-proclamation summarizing what he saw as American violations of the ethics of friendship, particularly as regards the events in Iloilo. The proclamation concluded as follows:

Such procedures, so foreign to the dictates of culture and the usages observed by civilized nations, gave me the right to act without observing the usual rules of intercourse. Nevertheless, in order to be correct to the end, I sent to General Otis commissioners charged to solicit him to desist from his rash enterprise, but they were not listened to. My government can not remain indifferent in view of such a violent and aggressive seizure of a portion of its territory by a nation which arrogated to itself the title champion of oppressed nations. Thus it is that my government is disposed to open hostilities if the American troops attempt to take forcible possession of the Visayan Islands. I denounce these acts before the world, in order that the conscience of mankind may pronounce its infallable verdict as to who are the true oppressors of nations and the tormentors of human kind.[73]

After some copies of that proclamation had been distributed, Aguinaldo ordered the recall of undistributed copies and issued another proclamation, which was published the same day in El Heraldo de la Revolucion, the official newspaper of the Philippine Republic. There, he said partly,

As in General Otis's proclamation he alluded to some instructions edited by His Excellency the President of the United States, referring to the administration of the matters in the Philippine Islands, I in the name of God, the root and fountain of all justice, and that of all the right which has been visibly granted to me to direct my dear brothers in the difficult work of our regeneration, protest most solemnly against this intrusion of the United States Government on the sovereignty of these islands. I equally protest in the name of the Filipino people against the said intrusion, because as they have granted their vote of confidence appointing me president of the nation, although I don't consider that I deserve such, therefore I consider it my duty to defend to death its liberty and independence.[74]

Otis, taking these two proclamations as a call to arms, strengthened American observation posts and alerted his troops. In the tense atmosphere, some 40,000 Filipinos fled Manila within a period of 15 days.[75]

Meanwhile, Felipe Agoncillo, who had been commissioned by the Philippine Revolutionary Government as Minister Plenipotentiary to negotiate treaties with foreign governments, and who had unsuccessfully sought to be seated at the negotiations between the U.S. and Spain in Paris, was now in Washington. On January 6, he filed a request for an interview with the President to discuss affairs in the Philippines. The next day the government officials were surprised to learn that messages to General Otis to deal mildly with the rebels and not to force a conflict had become known to Agoncillo, and cabled by him to Aguinaldo. At the same time came Aguinaldo's protest against General Otis signing himself "Military Governor of the Philippines".[68]

On January 8, Agoncillo gave out this statement:[68]

In my opinion the Filipino people, whom I represent, will never consent to become a colony dependency of the United States. The soldiers of the Filipino army have pledged their lives that they will not lay down their arms until General Aguinaldo tells them to do so, and they will keep that pledge, I feel confident.

The Filipino committees in London, Paris and Madrid about this time telegraphed to President McKinley as follows:

We protest against the disembarkation of American troops at Iloilo. The treaty of peace still unratified, the American claim to sovereignty is premature. Pray reconsider the resolution regarding Iloilo. Filipinos wish for the friendship of America and abhor militarism and deceit.[68]

On January 8, Aguinaldo received the following message from Teodoro Sandiko:

To the President of the Revolutionary Government, Malolos, from Sandico, Manila. 8 Jan., 1899, 9.40 p.m..: In consequence of the order of General Rios to his officers, as soon as the Filipino attack begins the Americans should be driven into the Intramuros district and the walled city should be set on fire. Pipi.[76]

The New York Times reported on January 8, that two Americans who had been guarding a waterboat in Iloilo had been attacked, one fatally, and that insurgents were threatening to destroy the business section of the city by fire; and on January 10 that a peaceful solution to the Iloilo issues may result but that Aguinaldo had issued a proclamation threatening to drive the Americans from the islands.[77][78]

By January 10, insurgents were ready to assume the offensive, but desired, if possible, to provoke the Americans into firing the first shot. They made no secret of their desire for conflict, but increased their hostile demonstrations and pushed their lines forward into forbidden territory. Their attitude is well illustrated by the following extract from a telegram sent by Colonel Cailles to Aguinaldo on January 10, 1899:[79]

Most urgent. An American interpreter has come to tell me to withdraw our forces in Maytubig fifty paces. I shall not draw back a step, and in place of withdrawing, I shall advance a little farther. He brings a letter from his general, in which he speaks to me as a friend. I said that from the day I knew that Maquinley (McKinley) opposed our independence I did not want any dealings with any American. War, war, is what we want. The Americans after this speech went off pale.

Aguinaldo approved the hostile attitude of Cailles, for there is a reply in his handwriting which reads:[79]

I approve and applaud what you have done with the Americans, and zeal and valour always, also my beloved officers and soldiers there. I believe that they are playing us until the arrival of their reinforcements, but I shall send an ultimatum and remain always on the alert.--E. A. Jan. 10, 1899.

On January 31, 1899, The Minister of Interior of the revolutionary First Philippine Republic, Teodoro Sandiko, signed a decree saying that President Aguinaldo had directed that all idle lands be planted to provide food for the people, in view of impending war with the Americans.[80]

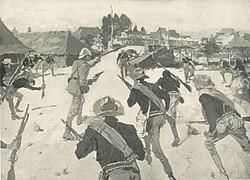

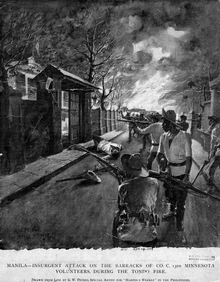

Outbreak of general hostilities

Worcester writes that General Otis' account of the opening of active hostilities was as follows:

On the night of February 2 they sent in a strong detachment to draw the fire of our outposts, which took up a position immediately in front and within a few yards of the same. The outpost was strengthened by a few of our men, who silently bore their taunts and abuse the entire night. This was reported to me by General MacArthur, whom I directed to communicate with the officer in command of the insurgent troops concerned. His prepared letter was shown me and approved, and the reply received was all that could be desired. However, the agreement was ignored by the insurgents and on the evening of February 4 another demonstration was made on one of our small outposts, which occupied a retired position at least 150 yards within the line which had been mutually agreed upon, an insurgent approaching the picket and refusing to halt or answer when challenged. The result was that our picket discharged his piece, when the insurgent troops near Santa Mesa opened a spirited fire on our troops there stationed.

The insurgents had thus succeeded in drawing the fire of a small outpost, which they had evidently labored with all their ingenuity to accomplish, in order to justify in some way their premeditated attack. It is not believed that the chief insurgent leaders wished to open hostilities at this time, as they were not completely prepared to assume the initiative. They desired two or three days more to perfect their arrangements, but the zeal of their army brought on the crisis which anticipated their premeditated action. They could not have delayed long, however, for it was their object to force an issue before American troops, then en route, could arrive in Manila.

Thus began the Insurgent attack, so long and so carefully planned for. We learn from the Insurgent records that the shot of the American sentry missed its mark. There was no reason why it should have provoked a hot return fire, but it did.

The result of the ensuing combat was not at all what the Insurgents had anticipated. The Americans did not drive very well. It was but a short time before they themselves were routed and driven from their positions.

Aguinaldo of course promptly advanced the claim that his troops had been wantonly attacked. The plain fact is that the Insurgent patrol in question deliberately drew the fire of the American sentry, and this was just as much an act of war as was the firing of the shot. Whether the patrol was acting under proper orders from higher authority is not definitely known.[81]

Other sources name the two specific U.S. soldiers involved in the first exchange of fire as Privates William Grayson and Orville Miller of the Nebraska Volunteers.[82]

Subsequent to the conclusion of the war, after analyzing captured insurgent papers, Major Major J. R. M. Taylor wrote, in part,

An attack on the United States forces was planned which should annihilate the little army in Manila, and delegations were appointed to secure the interference of foreign powers. The protecting cloak of pretense of friendliness to the United States was to be kept up until the last. While commissioners were appointed to negotiate with General Otis, secret societies were organized in Manila pledged to obey orders of the most barbarous character to kill and burn. The attack from without and the attack from within was to be on a set day and hour. The strained situation could not last. The spark was applied, either inadvertently or by design, on the 4th of February by an insurgent, willfully transgressing upon what, by their own admission, was within the agreed limits of the holding of the American troops. Hostilities resulted and the war was an accomplished fact.[83]

War

On February 4, Aguinaldo declared "That peace and friendly relations with the Americans be broken and that the latter be treated as enemies, within the limits prescribed by the laws of war."[84] On June 2, 1899, the Malolos Congress enacted and ratified a declaration of war on the United States, which was publicly proclaimed on that same day by Pedro Paterno, President of the Assembly.[85]

As before when fighting the Spanish, the Filipino rebels did not do well in the field. Aguinaldo and his provisional government escaped after the capture of Malolos on March 31, 1899 and were driven into northern Luzon. Peace feelers from members of Aguinaldo's cabinet failed in May when the American commander, General Ewell Otis, demanded an unconditional surrender. In 1901, Aguinaldo was captured and swore allegiance to the United States, marking one end to the war.

First Philippine Commission

President McKinley had appointed a five-person group headed by Dr. Jacob Schurman, president of Cornell University, on January 20, 1899, to investigate conditions in the islands and make recommendations.

The three civilian members of the Philippine Commission arrived in Manila on March 4, 1899, a month after the Battle of Manila which had begun armed conflict between U.S. and revolutionary Filipino forces. The commission published a proclamation containing assurances that the U.S. "... is anxious to establish in the Philippine Islands an enlightened system of government under which the Philippine people may enjoy the largest measure of home rule and the amplest liberty."

After meetings in April with revolutionary representatives, the commission requested authorization from McKinley to offer a specific plan. McKinley authorized an offer of a government consisting of "a Governor-General appointed by the President; cabinet appointed by the Governor-General; [and] a general advisory council elected by the people."[86] The Revolutionary Congress voted unanimously to cease fighting and accept peace and, on May 8, the revolutionary cabinet headed by Apolinario Mabini was replaced by a new "peace" cabinet headed by Pedro Paterno. At this point, General Antonio Luna arrested Paterno and most of his cabinet, returning Mabini and his cabinet to power. After this, the commission concluded that "... The Filipinos are wholly unprepared for independence ... there being no Philippine nation, but only a collection of different peoples."[87]

In the report that they issued to the president the following year, the commissioners acknowledged Filipino aspirations for independence; they declared, however, that the Philippines was not ready for it.[88]

On November 2, 1899, The commission issued a preliminary report containing the following statement:

Should our power by any fatality be withdrawn, the commission believe that the government of the Philippines would speedily lapse into anarchy, which would excuse, if it did not necessitate, the intervention of other powers and the eventual division of the islands among them. Only through American occupation, therefore, is the idea of a free, self-governing, and united Philippine commonwealth at all conceivable. And the indispensable need from the Filipino point of view of maintaining American sovereignty over the archipelago is recognized by all intelligent Filipinos and even by those insurgents who desire an American protectorate. The latter, it is true, would take the revenues and leave us the responsibilities. Nevertheless, they recognize the indubitable fact that the Filipinos cannot stand alone. Thus the welfare of the Filipinos coincides with the dictates of national honour in forbidding our abandonment of the archipelago. We cannot from any point of view escape the responsibilities of government which our sovereignty entails; and the commission is strongly persuaded that the performance of our national duty will prove the greatest blessing to the peoples of the Philippine Islands.[89][90]

Specific recommendations included the establishment of civilian government as rapidly as possible (the American chief executive in the islands at that time was the military governor), including establishment of a bicameral legislature, autonomous governments on the provincial and municipal levels, and a system of free public elementary schools.[91]

Second Philippine Commission

The Second Philippine Commission (the Taft Commission), appointed by McKinley on March 16, 1900, and headed by William Howard Taft, was granted legislative as well as limited executive powers.[92] On September 1, the Taft Commission began to exercise legislative functions.[93] Between September 1900 and August 1902, it issued 499 laws, established a judicial system, including a supreme court, drew up a legal code, and organized a civil service.[94] The 1901 municipal code provided for popularly elected presidents, vice presidents, and councilors to serve on municipal boards. The municipal board members were responsible for collecting taxes, maintaining municipal properties, and undertaking necessary construction projects; they also elected provincial governors.[91]

Establishment of civil government

On March 3, 1901 the U.S. Congress passed the Army Appropriation Act containing (along with the Platt Amendment on Cuba) the Spooner Amendment which provided the President with legislative authority to establish of a civil government in the Philippines.[95] Up until this time, the President been administering the Philippines by virtue of his war powers.[96] On July 1, 1901, civil government was inaugurated with William H. Taft as the Civil Governor. Later, on February 3, 1903, the U.S. Congress would change the title of Civil Governor to Governor-General.[97]

A highly centralized public school system was installed in 1901, using English as the medium of instruction. This created a heavy shortage of teachers, and the Philippine Commission authorized the Secretary of Public Instruction to bring to the Philippines 600 teachers from the U.S.A. — the so-called Thomasites. Free primary instruction that trained the people for the duties of citizenship and avocation was enforced by the Taft Commission per instructions of President McKinley.[98] Also, the Catholic Church was disestablished, and a considerable amount of church land was purchased and redistributed.

Official end to the war

The Philippine Organic Act of July 1902 approved, ratified, and confirmed McKinley's Executive Order establishing the Philippine Commission, and also stipulated that the bicameral Philippine Legislature would be established composed of an elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly and the appointed Philippine Commission as the upper house. The act also provided for extending the United States Bill of Rights to the Philippines.[91][99]

On July 2, 1902 the Secretary of War telegraphed that the insurrection against the sovereign authority of the U.S. having come to an end, and provincial civil governments having been established, the office of Military Governor was terminated.[51] On July 4, Theodore Roosevelt, who had succeeded to the U.S. Presidency after the assassination of President McKinley on September 5, 1901 proclaimed a full and complete pardon and amnesty to all persons in the Philippine archipelago who had participated in the conflict.[51][100]

On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo proclaimed that the Philippine–American War had ended on April 16, 1902 with the surrender of General Miguel Malvar, and declared the centennial anniversary of that date as a national working holiday and as a special non-working holiday in the Province of Batangas and in the Cities of Batangas, Lipa and Tanaun.[101]

Post-1902 hostilities

Some sources have suggested that the war unofficially continued for nearly a decade, since bands of guerrillas, quasi-religious armed groups and other resistance groups continued to roam the countryside, still clashing with American Army or Philippine Constabulary patrols. American troops and the Philippine Constabulary continued hostilities against such resistance groups until 1913.[102] Some historians consider these unofficial extensions to be part of the war.[103]

US colonization: the "Insular Government" (1901–1935)

The 1902 Philippine Organic Act was a constitution for the Insular Government, as the U.S. colonial administration was known. This was a form of territorial government that reported to the Bureau of Insular Affairs. The act provided for a Governor-General appointed by the U.S. president and an elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly. It also disestablished the Catholic Church as the state religion. The United States government, in an effort to resolve the status of the friars, negotiated with the Vatican. The church agreed to sell the friars' estates and promised gradual substitution of Filipino and other non-Spanish priests for the friars. It refused, however, to withdraw the religious orders from the islands immediately, partly to avoid offending Spain. In 1904 the administration bought for $7.2 million the major part of the friars' holdings, amounting to some 166,000 hectares (410,000 acres), of which one-half was in the vicinity of Manila. The land was eventually resold to Filipinos, some of them tenants but the majority of them estate owners.[91]

In socio-economic terms, the Philippines made solid progress in this period. Foreign trade had amounted to 62 million pesos in 1895, 13% of which was with the United States. By 1920, it had increased to 601 million pesos, 66% of which was with the United States.[104] A health care system was established which, by 1930, reduced the mortality rate from all causes, including various tropical diseases, to a level similar to that of the United States itself. The practices of slavery, piracy and headhunting were suppressed but not entirely extinguished.

Two years after completion and publication of a census, a general election was conducted for the choice of delegates to a popular assembly. An elected Philippine Assembly was convened in 1907 as the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the Philippine Commission as the upper house. Every year from 1907 the Philippine Assembly and later the Philippine Legislature passed resolutions expressing the Filipino desire for independence.

Philippine nationalists led by Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña enthusiastically endorsed the draft Jones Bill of 1912, which provided for Philippine independence after eight years, but later changed their views, opting for a bill which focused less on time than on the conditions of independence. The nationalists demanded complete and absolute independence to be guaranteed by the United States, since they feared that too-rapid independence from American rule without such guarantees might cause the Philippines to fall into Japanese hands. The Jones Bill was rewritten and passed Congress in 1916 with a later date of independence.[105]

The law, officially the Philippine Autonomy Act but popularly known as the Jones Law, served as the new organic act (or constitution) for the Philippines. Its preamble stated that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law maintained the Governor-General of the Philippines, appointed by the President of the United States, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature to replace the elected Philippine Assembly (lower house); it replaced the appointive Philippine Commission (upper house) with an elected senate.[106]

The Filipinos suspended their independence campaign during the First World War and supported the United States against Germany. After the war they resumed their independence drive with great vigor.[107] On March 17, 1919, the Philippine Legislature passed a "Declaration of Purposes", which stated the inflexible desire of the Filipino people to be free and sovereign. A Commission of Independence was created to study ways and means of attaining liberation ideal. This commission recommended the sending of an independence mission to the United States.[108] The "Declaration of Purposes" referred to the Jones Law as a veritable pact, or covenant, between the American and Filipino peoples whereby the United States promised to recognize the independence of the Philippines as soon as a stable government should be established. U.S. Governor-General of the Philippines Francis Burton Harrison had concurred in the report of the Philippine legislature as to a stable government.

The Philippine legislature funded an independence mission to the U.S. in 1919. The mission departed Manila on February 28 and met in the U.S. with and presented their case to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker.[109] U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, in his 1921 farewell message to Congress, certified that the Filipino people had performed the condition imposed on them as a prerequisite to independence, declaring that, this having been done, the duty of the U.S. is to grant Philippine independence.[110] The Republican Party then controlled Congress and the recommendation of the outgoing Democratic president was not heeded.[109]

After the first independence mission, public funding of such missions was ruled illegal. Subsequent independence missions in 1922, 1923, 1930, 1931 1932, and two missions in 1933 were funded by voluntary contributions. Numerous independence bills were submitted to the U.S. Congress, which passed the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Bill on December 30, 1932. U.S. President Herbert Hoover vetoed the bill on January 13, 1933. Congress overrode the veto on January 17, and the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act became U.S. law. The law promised Philippine independence after 10 years, but reserved several military and naval bases for the United States, as well as imposing tariffs and quotas on Philippine exports. The law also required the Philippine Senate to ratify the law. Manuel L. Quezon urged the Philippine Senate to reject the bill, which it did. Quezon himself led the twelfth independence mission to Washington to secure a better independence act. The result was the Tydings–McDuffie Act of 1934 which was very similar to the Hare-Hawes-Cutting Act except in minor details. The Tydings-McDuffie Act was ratified by the Philippine Senate. The law provided for the granting of Philippine independence by 1946.[111]

The Tydings–McDuffie Act provided for the drafting and guidelines of a Constitution, for a 10-year "transitional period" as the Commonwealth of the Philippines before the granting of Philippine independence. On May 5, 1934, the Philippines legislature passed an act setting the election of convention delegates. Governor-General Frank Murphy designated July 10 as the election date, and the convention held its inaugural session on July 30. The completed draft constitution was approved by the convention on February 8, 1935, approved by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt on March 23, and ratified by popular vote on May 14. The first election under the constitution was held on September 17, and on November 15, 1935, the Commonwealth was put into place.[112]

Philippine Commonwealth (1935–1946)

It was planned that the period 1935–1946 would be devoted to the final adjustments required for a peaceful transition to full independence, a great latitude in autonomy being granted in the meantime. Instead there was war with Japan.[113]

On May 14, 1935, an election to fill the newly created office of President of the Commonwealth of the Philippines was won by Manuel L. Quezon (Nacionalista Party), and a Filipino government was formed on the basis of principles superficially similar to the U.S. Constitution. The Commonwealth as established in 1935 featured a very strong executive, a unicameral national assembly, and a supreme court composed entirely of Filipinos for the first time since 1901.

The new government embarked on an ambitious agenda of establishing the basis for national defense, greater control over the economy, reforms in education, improvement of transport, the colonization of the island of Mindanao, and the promotion of local capital and industrialization. The Commonwealth however, was also faced with agrarian unrest, an uncertain diplomatic and military situation in South East Asia, and uncertainty about the level of United States commitment to the future Republic of the Philippines.

In 1939–40, the Philippine Constitution was amended to restore a bicameral Congress, and permit the re-election of President Quezon, previously restricted to a single, six-year term.

During the Commonwealth years, Philippines sent one elected Resident Commissioner to the United States House of Representatives, as Puerto Rico currently does today.

Japanese occupation and World War II (1941–1945)

A few hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched air raids in several cities and US military installations in the Philippines on December 8, and on December 10, the first Japanese troops landed in Northern Luzon. Filipino pilot Captain Jesús A. Villamor, leading a flight of three P-26 "Peashooter" fighters of the 6th Pursuit Squadron, distinguished himself by attacking two enemy formations of 27 planes each and downing a much-superior Japanese Zero, for which he was awarded the U.S. Distinguished Service Cross. The two other planes in that flight, flown by Lieutenants César Basa and Geronimo Aclan, were shot down.[114]

As the Japanese forces advanced, Manila was declared an open city to prevent it from destruction, meanwhile, the government was moved to Corregidor. In March 1942, General MacArthur and President Quezon fled the country. Guerrilla units harassed the Japanese when they could, and on Luzon native resistance was strong enough that the Japanese never did get control of a large part of the island.

General Douglas MacArthur, commander of the United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), was forced to retreat to Bataan. Manila was occupied by the Japanese on January 2, 1942. The fall of Bataan was on April 9, 1942 with Corregidor Island, at the mouth of Manila Bay, surrendering on May 6.[115]

The Commonwealth government by then had exiled itself to Washington, DC, upon the invitation of President Roosevelt; however many politicians stayed behind and collaborated with the occupying Japanese. The Philippine Commonwealth Army continued to fight the Japanese in a guerrilla war and were considered auxiliary units of the United States Army. Several Philippine Commonwealth military awards, such as the Philippine Defense Medal, Independence Medal, and Liberation Medal, were awarded to both the United States and Philippine Armed Forces.

The Hukbalahap, a communist guerilla movement formed by peasant farmers in Central Luzon, did most of the fighting. The Hukbalahap, also known as Huks, resisted invaders and punished the people who collaborated with the Japanese, but did not have a well-disciplined organization, and were later seen as a threat to the Manila government.[116] Before MacArthur came back, the effectiveness of the guerilla movement had decimated Japanese control, limiting it to only 12 out of the 48 provinces.

In October 1944, MacArthur had gathered enough additional troops and supplies to begin the retaking of the Philippines, landing with Sergio Osmeña who had assumed the Presidency after Quezon's death. The Philippine Constabulary went on active service under the Philippine Commonwealth Army on October 28, 1944 during liberation under the Commonwealth regime.

The battles entailed long fierce fighting and some of the Japanese continued to fight after the official surrender of the Empire of Japan on September 2, 1945.[117]

After their landing, Filipino and American forces also undertook measures to suppress the Huk movement, which was founded to fight the Japanese Occupation. The Filipino and American forces removed local Huk governments and imprisoned many high-ranking members of the Philippine Communist Party. While these incidents happened, there was still fighting against the Japanese forces and, despite the American and Philippine measures against the Huk, they still supported American and Filipino soldiers in the fight against the Japanese.

Over a million Filipinos (including regular and constable soldiers, recognized guerrillas and non-combatant civilians) had been killed in the war. The 1947 final report of the High Commissioner to the Philippines documents massive damage to most coconut mills and sugar mills; inter-island shipping had all been destroyed or removed; concrete highways had been broken up for use on military airports; railways were inoperative; Manila was 80 percent destroyed, Cebu 90 percent, and Zamboanga 95 percent.[118]

Independence (1946)

Philippine independence came on July 4, 1946, with the signing of the Treaty of Manila between the governments of the United States and the Philippines. The treaty provided for the recognition of the independence of the Republic of the Philippines and the relinquishment of American sovereignty over the Philippine Islands.[119] From 1946 to 1961, Independence Day was observed on July 4. On May 12, 1962, President Macapagal issued Presidential Proclamation No. 28, proclaiming Tuesday, June 12, 1962 as a special public holiday throughout the Philippines.[120][121] In 1964, Republic Act No. 4166 changed the date of Independence Day from July 4 to June 12 and renamed the July 4 holiday as Philippine Republic Day.[122]

World War II veteran benefits

During World War II, over 200,000 Filipinos fought in defense of the United States against the Japanese in the Pacific theater of military operations, where more than half died. As a commonwealth of the United States before and during the war, Filipinos were legally American nationals. With American nationality, Filipinos were promised all the benefits afforded to those serving in the armed forces of the United States.[123] In 1946, Congress passed the Rescission Act (38 U.S.C. § 107) which stripped Filipinos of the benefits they were promised.[123]

Since the passage of the Rescission Act, many Filipino veterans have traveled to the United States to lobby Congress for the benefits promised to them for their service and sacrifice. Over 30,000 of such veterans live in the United States today, with most being United States citizens. Sociologists introduced the phrase "Second Class Veterans" to describe the plight of these Filipino Americans. Beginning in 1993, numerous bills titled Filipino Veterans Fairness Act were introduced in Congress to return the benefits taken away from these veterans, only to die in committee. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, signed into law on February 17, 2009, included provisions to pay benefits to the 15,000 remaining veterans.[124]

On January 6, 2011 Jackie Speier (D-CA), U.S. Representative for California's 12th congressional district, serving since 2008, introduced a bill seeking to make Filipino WW-II veterans eligible for the same benefits available to U.S. veterans. In a news conference to outline the bill, Speier estimated that approximately 50,000 Filipino veterans survive.[125][126]

See also

- Spanish–American War

- Philippine–American War

- Moro Rebellion

- Negros Revolution

- Republic of Negros

- Republic of Zamboanga

- Insular Government of the Philippine Islands

- Commonwealth of the Philippines

- Japanese invasion of the Philippines

- Japanese occupation of the Philippines

- Second Philippine Republic

- Independence Day (Philippines)

- History of the Philippines

- Prehistory of the Philippines

- History of the Philippines (Pre-Colonial Era 900–1521)

- History of the Philippines (Spanish Era 1521–1898)

- History of the Philippines (Third Republic 1946–65)

- History of the Philippines (Marcos Era 1965–86)

- History of the Philippines (Contemporary Era 1986–present)

- List of sovereign state leaders in the Philippines

Notes

- Unrecognized insurgent governments (1898–1902):

- Dictatorial Government of the Philippines (May 24, 1898 – June 23, 1898)

- Revolutionary Government of the Philippines (June 23, 1898 – January 23, 1899)

- First Philippine Republic (January 23, 1899 – March 23, 1901)

- Tagalog Republic (1902–1904)

References

Citations

- "Treaty of Peace Between the United States and Spain; December 10, 1898". The Avalon Project. New Haven, Connecticut: Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale Law School. 2008. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- Corpus Juris (2014), "Tydings-McDuffie Act", Constitutions, Manila, Philippines: Corpus Juris, retrieved June 11, 2014

- Aguinaldo 1899 Ch.1

- Aguinaldo 1899 Ch.2

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 92–94Ch.5

- Trask 1996, pp. 56–8.

- Beede 1994, p. 148.

- Howland, Harold (1921). Theodore Roosevelt and his times: a chronicle of the progressive movement. p. 245. ISBN 978-1279815199.

- Battle of Manila Bay, 1 May 1898 Archived January 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Department of the Navy — Naval Historical Center. Retrieved on October 10, 2007

- Dewey, George (2003). "The Battle of Manila Bay". Archives:Eyewitness Accounts. The War Times Journal. Retrieved June 15, 2014.

- Titherington 1900, pp. 357–8

- Agoncillo 1990, pp. 192–4

- Worcester 1914, p. 57Ch.3

- Halstead 1898, p. 95ch.10

- Guevara, Sulpicio, ed. (2005), "Philippine Declaration of Independence", The laws of the first Philippine Republic (the laws of Malolos) 1898–1899, Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Library (published 1972), retrieved January 2, 2013

- "Philippine History". DLSU-Manila. Archived from the original on August 22, 2006. Retrieved August 21, 2006.

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 413–417Appendix A

- Guevara 1972, p. 10

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 423–429Appendix C.

- Guevara 1972, p. 35

- Aguinaldo 1899 Ch.3

- Worcester 1914, p. 19Ch.2

- Worcester 1914, p. 21Ch.2

- Halstead 1898, p. 311Ch.28

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 100Ch.5

- Worcester 1914, p. 60

- Worcester 1914, p. 154Ch.7

- Worcester 1914, p. 61

- Halstead 1898, p. 97Ch.10

- Worcester 1914, p. 63Ch.3

- Worcester 1914, p. 55Ch.3

- Halstead 1898, p. 105Ch.10

- Worcester 1914, p. 69Ch.3

- Halstead 1898, p. 108Ch.10

- Wrocester 1914, p. 77Ch.3

- Wrocester 1914, p. 79Ch.3

- "WAR SUSPENDED, PEACE ASSURED; President Proclaims a Cessation of Hostilities" (PDF), The New York Times, August 12, 1898, retrieved February 6, 2008

- Halstead 1898, p. 177Ch.15

- "Protocol of Peace : Embodying the Terms of a Basis for the Establishment of Peace Between the Two Countries". August 12, 1898.

- "Proclamation 422 – Suspension of Hostilities with Spain". American Presidency Project. University of California. August 12, 1898.

- Karnow 1990, p. 123

- Agoncillo 1990, p. 196

- The World of 1898: The Spanish–American War, U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved June 15, 2014

- The World of 1898: the Spanish–American War, U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved October 10, 2007

- "Our flag is now waving over Manila", San Francisco Chronicle, retrieved December 20, 2008

- Trask 1996, p. 419

- Karnow 1990, pp. 123–4, Wolff 2006, p. 119

- Lacsamana 2006, p. 126.

- Halstead 1898, pp. 110–112

- Elliott 1917, p. 509.

- "GENERAL AMNESTY FOR THE FILIPINOS; Proclamation Issued by the President" (PDF). The New York Times. July 4, 1902.

- Otis, Elwell Stephen (1899). "Annual report of Maj. Gen. E.S. Otis, U.S.V., commanding Department of the Pacific and 8th Army Corps, military governor in the Philippine Islands". Annual Report of the Major-General Commanding the Army. 2. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 146.

- Zaide 1994, p. 279Ch.21

- Halstead 1898, p. 315Ch.28

- Taylor 1907, p. 19

- Taylor 1907, p. 20

- Worcester 1914, p. 83Ch.4

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927). The Development of Philippine Politics. Oriental commercial. p. 132.

- Halstead 1898, pp. 176–178Ch.15

- Miller 1984, p. 20

- Miller 1984, pp. 20–1

- Miller 1984, p. 24

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 430–445Appendix D

- Price, Matthew C. (2008). The Advancement of Liberty: How American Democratic Principles Transformed the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-313-34618-7.

- "TREATY BETWEEN SPAIN AND THE UNITED STATE FOR CESSION OF OUTLYING ISLANDS OF THE PHILIPPINES" (PDF). University of the Philippines. November 7, 1900. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 26, 2012.

- President William McKinley (December 21, 1898), McKinley's Benevolent Assimilation Proclamation, msc.edu.ph, retrieved February 10, 2008

- "PRESIDENT TO FILIPINOS; Order Expressing His Intentions Proclaimed to Them" (PDF), The New York Times, January 6, 1899, retrieved February 10, 2008

- Halstead 1898, p. 316

- Miller 1984, p. 50

- The text of the amended version published by General Otis is quoted in its entirety in José Roca de Togores y Saravia; Remigio Garcia; National Historical Institute (Philippines) (2003). Blockade and siege of Manila. National Historical Institute. pp. 148–50. ISBN 978-971-538-167-3.

See also Wikisource:Letter from E.S. Otis to the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands, January 4, 1899. - Wolff 2006, p. 200

- Miller 1984, p. 52

- Agoncillo 1997, pp. 356–7.

- Agoncillo 1997, p. 357.

- Agoncillo 1997, pp. 357–8.

- Taylor 1907, p. 39

- "BLOODSHED AT ILOILO; Two Americans Attacked and One Fatally Wounded by Natives." (PDF), The New York Times, January 8, 1899, retrieved February 10, 2008

- "THE PHILIPPINE CLIMAX; Peaceful Solution of the Iloilo Issue May Result To-day. AGUINALDO'S SECOND ADDRESS He Threatened to Drive the Americans from the Islands – Manifesto Was Recalled" (PDF), The New York Times, January 10, 1899, retrieved February 10, 2008

- Worcester 1914, p. 93Ch.4

- Guevara 1972, p. 124

- Worcester 1914, p. 96Ch.4

- Blitz 2000, p. 32, Blanchard 1996, p. 130

- Taylor 1907, p. 5

- Halstead 1918, p. 318Ch.28

- Kalaw 1927, pp. 199–200Ch.7

- Golay 1997, p. 49.

- Golay 1997, pp. 50–51.

- Worcester 1914, p. 199Ch.9

- "The Philippines : As viewed by President McKinley's Special Commissioners". The Daily Star. 7 (2214). Fredricksburg, Va. November 3, 1899.

- Report Philippine Commission, Vol. I, p. 183.

- Seekins 1993

- Kalaw 1927, p. 453Appendix F

- Zaide 1994, p. 280Ch.21

- Chronology for the Philippine Islands and Guam in the Spanish–American War, U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved February 16, 2008

- Piedad-Pugay, Chris Antonette. "The Philippine Bill of 1902: Turning Point in Philippine Legislation". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved July 9, 2013.

- Jernegan 2009, pp. 57–58

- Zaide 1994, p. 281Ch.21

- Historical Perspective of the Philippine Educational System, RP Department of education, archived from the original on July 16, 2011, retrieved March 11, 2008

- The Philippine Bill of July 1902, Chan Robles law library, July 1, 1902, retrieved July 31, 2010

- Worcester 1914, p. 180Ch.9

- "Presidential Proclamation No. 173 S. 2002". Official Gazette. April 9, 2002.

- "PNP History", Philippine National Police, Philippine Department of Interior and Local Government, archived from the original on June 17, 2008, retrieved August 29, 2009

- Constantino 1975, pp. 251–3

- Reyes, Jose (1923). Legislative history of America's economic policy toward the Philippines. Studies in history, economics and public law. 106 (2 ed.). Columbia University. pp. 192 of 232.

- Wong Kwok Chu, "The Jones Bills 1912–16: A Reappraisal of Filipino Views on Independence," Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 1982 13(2): 252–269

- Philippine Autonomy Act of 1916 (Jones Law)

- Zaide 1994, p. 312Ch.24

- Zaide 1994, pp. 312–313Ch.24

- Zaide 1994, p. 313

- Kalaw 1921, pp. 144–146

- Zaide 1994, pp. 314–5Ch.24

- Zaide 1994, pp. 315–9Ch.24

- Brands 1992, pp. 158–81.

- Zaide 1994, p. 325Ch.25

- Zaide 1994, pp. 329–31Ch.25

- Hunt, Michael (2004). The World Transformed. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-937102-0.

- Zaide 1994, pp. 323–35Ch.25

- J. L. Vellut, "Japanese reparations to the Philippines," Asian Survey 3 (Oct. 1993): 496–506.

- TREATY OF GENERAL RELATIONS BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES. SIGNED AT MANILA, ON 4 JULY 1946 (PDF), United Nations, archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011, retrieved December 10, 2007

- Diosdado Macapagal, Proclamation No. 28 Declaring June 12 as Philippine Independence Day, Philippine History Group of Los Angeles, archived from the original on May 12, 2009, retrieved November 11, 2009

- Manuel S. Satorre Jr., President Diosdado Macapagal set RP Independence Day on June 12, .positivenewsmedia.net, archived from the original on July 24, 2011, retrieved December 10, 2008

- AN ACT CHANGING THE DATE OF PHILIPPINE INDEPENDENCE DAY FROM JULY FOUR TO JUNE TWELVE, AND DECLARING JULY FOUR AS PHILIPPINE REPUBLIC DAY, FURTHER AMENDING FOR THE PURPOSE SECTION TWENTY-NINE OF THE REVISED ADMINISTRATIVE CODE, Chanrobles Law Library, August 4, 1964, retrieved November 11, 2009

- The Filipino Veterans Movement, pbs.org, retrieved November 14, 2007

- Josh Levs (February 23, 2009), U.S. to pay 'forgotten' Filipino World War II veterans, CNN

- "Speier Seeks To Extend Military Benefits To Filipino WWII Vets". CBS News. January 10, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

- "H.R.210 - Filipino Veterans Fairness Act of 2011". congress.gov. January 6, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2020.

Bibliography

- Agoncillo, Teodoro Andal (1990), "11. The Revolution Second Phase", History of the Filipino People (Eighth ed.), University of the Philippines, pp. 187–198, ISBN 971-8711-06-6

- Agoncillo, Teodoro Andal (1997), Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic, University of the Philippines Press, ISBN 978-971-542-096-9

- Beede, Benjamin R. (1994), The War of 1898, and U.S. interventions, 1898–1934: an encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-8240-5624-7

- Blanchard, William H. (1996), "9. Losing Stature in the Philippines", Neocolonialism American Style, 1960–2000, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-30013-5

- Blitz, Amy (2000), "Conquest and Coercion: Early U.S. Colonialism, 1899–1916", The Contested State: American Foreign Policy and Regime Change in the Philippines, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-8476-9935-8

- Brands, Henry William (1992), Bound to empire: the United States and the Philippines, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-507104-7 questia.com

- Burns, Adam D. "Adapting to Empire: William H. Taft, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Philippines, 1900-08," Comparative American Studies 11 (Dec. 2013), 418–33.

- Constantino, Renato (1975), The Philippines: A Past Revisited, ISBN 971-8958-00-2

- Elliott, Charles Burke (1917), The Philippines: To the End of the Commission Government, a Study in Tropical Democracy

- Golay, Frank H. (1997), Face of empire: United States-Philippine relations, 1898–1946, Ateneo de Manila University Press, ISBN 978-971-550-254-2.

- Halstead, Murat (1898), "XXVIII. Battles with the Filipinos before Manila", The Story of the Philippines and Our New Possessions, Including the Ladrones, Hawaii, Cuba and Porto Rico

- Jernegan, Prescott F (2009), The Philippine Citizen, BiblioBazaar, LLC, ISBN 978-1-115-97139-3

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1921), The Present Government of the Philippines, Oriental commercial, ISBN 1-4067-4636-3, retrieved March 12, 2008(Note: 1. The book cover incorrectly lists author as "Maximo M Lalaw", 2. Originally published in 1921 by The McCullough Printing Co., Manila)

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), "V. The Katipunan revolt under Bonifacio and Aguinaldo", The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, pp. 69–98, retrieved February 7, 2008

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), "VI. The Revolutionary Government", The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, pp. 99–163, retrieved February 7, 2008

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), "VII. The Opposition to American Sovereignty (1898–1901)", The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, pp. 99–163, retrieved February 7, 2008

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), "Appendix A. Act of the Proclamation of Independence of the Filipino People", The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, pp. 413–417, retrieved February 7, 2008(English translation by the author. Original in Spanish)

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), "Appendix C. Aguinaldo's Proclamation of June 23, 1898, Establishing the Revolutionary Government", The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, pp. 423–429, retrieved September 7, 2009

- Kalaw, Maximo Manguiat (1927), "Appendix D. The Political Constitution of the Philippine Republic", The Development of Philippine Politics, Oriental commercial, pp. 430–445, retrieved February 7, 2008(English translation by the author. Original in Spanish)

- Kalaw, Maximo M. (1927), "Appendix F: President McKinley's Instructions to the Taft Commission", The development of Philippine politics, Oriental commercial, pp. 452–459, retrieved January 21, 2008

- Karnow, Stanley (1990), In Our Image, Century, ISBN 978-0-7126-3732-9

- Lacsamana, Leodivico Cruz (2006), Philippine history and government, Phoenix Publishing House, ISBN 978-971-06-1894-1CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Stuart Creighton (1984), Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899–1903 (4th edition, reprint ed.), Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-03081-5

- Seekins, Donald M. (1993), "The First Phase of United States Rule, 1898–1935", in Dolan, Ronald E. (ed.), Philippines: A Country Study (4th ed.), Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, retrieved December 25, 2007

- Trask, David F. (1996), The war with Spain in 1898, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 978-0-8032-9429-5