Bill of rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and private citizens.

Bills of rights may be entrenched or unentrenched. An entrenched bill of rights cannot be amended or repealed by a country's legislature through regular procedure, instead requiring a supermajority or referendum; often it is part of a country's constitution, and therefore subject to special procedures applicable to constitutional amendments. A bill of rights that is not entrenched is a normal statute law and as such can be modified or repealed by the legislature at will.

In practice, not every jurisdiction enforces the protection of the rights articulated in its bill of rights.

History

The history of legal charters asserting certain rights for particular groups goes back to the Middle Ages and earlier. An example is Magna Carta, an English legal charter agreed between the King and his barons in 1215.[1] In the early modern period, there was renewed interest in Magna Carta.[2] English common law judge Sir Edward Coke revived the idea of rights based on citizenship by arguing that Englishmen had historically enjoyed such rights. The Petition of Right 1628, the Habeas Corpus Act 1679 and the Bill of Rights 1689 established certain rights in statute.

In America, the English Bill of Rights was one of the influences on the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights, which in turn influenced the United States Declaration of Independence later that year.[3]

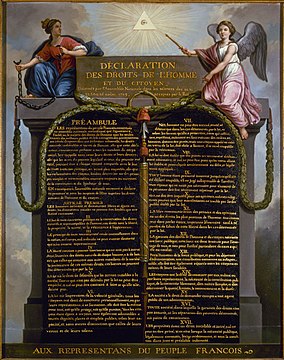

Inspired by the Age of Enlightenment, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen asserted the universality of rights.[4] It was adopted in 1789 by France's National Constituent Assembly, during the period of the French Revolution.

After the Constitution of the United States was adopted in 1789, the United States Bill of Rights was ratified in 1791.[5][6][7]

The 20th century saw different groups draw on these earlier documents for influence when drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.[8]

Exceptions in Western democracies

The constitution of the United Kingdom remains uncodified.[1] However, the Bill of Rights of 1689 is part of UK law. The Human Rights Act 1998 also incorporates the rights contained in the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law. Recent infringements of liberty, democracy and the rule of law have led to demands for a new comprehensive British Bill of Rights upheld by a new independent Supreme Court with the power to nullify government laws and policies violating its terms.[9]

Australia is the only common law country with neither a constitutional nor federal legislative bill of rights to protect its citizens, although there is ongoing debate in many of Australia's states.[10][11] In 1973, Federal Attorney-General Lionel Murphy introduced a human rights Bill into parliament, although it was never passed.[12] In 1984, Senator Gareth Evans drafted a Bill of Rights, but it was never introduced into parliament, and in 1985, Senator Lionel Bowen introduced a bill of rights, which was passed by the House of Representatives, but failed to pass the Senate.[13] Former Australian Prime Minister John Howard has argued against a bill of rights for Australia on the grounds it would transfer power from elected politicians (populist politics) to unelected (constitutional) judges and bureaucrats.[14][15] Victoria, Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) are the only states and territories to have a human rights Act.[16][17][18] However, the principle of legality present in the Australian judicial system, seeks to ensure that legislation is interpreted so as not to interfere with basic human rights, unless legislation expressly intends to interfere.[19]

List of bills of rights

General

- Charter of Liberties (1100; England) rights of inheritance and marriage, amnesty, and environmental protection (forest)

- Magna Carta (1215; England) rights for barons

- Great Charter of Ireland (1216; Ireland) rights for barons

- Golden Bull of 1222 (1222; Hungary) rights for nobles

- Statute of Kalisz (1264; Kingdom of Poland) Jewish residents' rights

- Charter of Kortenberg (1312; Belgium) rights for all citizens "rich and poor"

- Dušan's Code (1349; Serbia)

- Twelve Articles (1525; Germany)

- Pacta conventa (1573; Poland)

- Henrician Articles (1573; Poland)

- Petition of Right (1628; England)

- Bill of Rights 1689 (England) and Claim of Right Act 1689 (Scotland) This applied to all British Colonies of the time, and was later entrenched in the laws of those colonies that became nations - for instance in Australia with the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865 and reconfirmed by the Statute of Westminster 1931

- Virginia Declaration of Rights (June 1776)

- Preamble to the United States Declaration of Independence (July 1776)

- Chapter 1 of the Pennsylvania Constitution (July 1776)[20]

- Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789; France)

- Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution (completed in 1789, ratified in 1791)

- Declaration of the Rights of the People (1811; Venezuela)

- Article I of the Constitution of Connecticut (1818)

- Constitution of Greece (1822; Epidaurus)

- Hatt-ı Hümayun (1856; Ottoman Empire)

- Article I of the Constitution of Texas (1875)

- Basic rights and liberties in Finland (1919)

- Articles 13-28 of the Constitution of Italy (1947)

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948, United Nations)

- Fundamental rights and duties of citizens in People's Republic of China (1949)

- European Convention on Human Rights (1950)

- Fundamental Rights of Indian citizens (1950)

- Implied Bill of Rights (a theory in Canadian constitutional law)

- Canadian Bill of Rights (1960)

- International Bill of Human Rights (1976)

- Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms (1976)

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982)

- Article III of the Constitution of the Philippines (1987)

- Article 5 of the Constitution of Brazil (1988)

- New Zealand Bill of Rights Act (1990)

- Charter of Fundamental Rights and Basic Freedoms of the Czech Republic (1991)

- Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance (1991)

- Chapter 2 of the Constitution of South Africa (entitled "Bill of Rights") (1996)

- Human Rights Act 1998 (United Kingdom)

- Human Rights Act 2004 (Australian Capital Territory)

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (2005)

- Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities (2006; Australian state of Victoria)

- Chapter Four of the Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013)

- Queensland Human Rights Act 2018 (2019; Australian state of Queensland)

Specifically targeted documents

- Consumer Bill of Rights

- Homeless Bill of Rights

- Taxpayer Bill of Rights

- Academic Bill of Rights,

- Veterans' Bill of Rights

- G.I. Bill of Rights, better known as the G.I. Bill

- Homosexual Bill of Rights, drafted by North American Conference of Homophile Organizations

- Library Bill of Rights, published by the American Library Association

- Environmental Bill of Rights or Agenda 21

- Creator's Bill of Rights, comic writers and artists

- Donor's Bill of Rights, for philanthropic donors

- Law Enforcement Officers' Bill of Rights

- California Voter Bill of Rights, adaptation of the Voting Rights Act

- Islamic Bill of Rights for Women in the Mosque

- New Jersey Anti-Bullying Bill of Rights Act

- Credit Cardholders' Bill of Rights, contained within the Credit CARD Act of 2009

- Sexual Assault Survivors' Bill of Rights (Sexual Assault Survivors' Rights Act)

See also

- Proposed British Bill of Rights

- Inalienable rights

- International Bill of Human Rights

- International human rights instruments

- Natural rights

- Rule of law

- Second Bill of Rights

References

- Rau, Zbigniew; Żurawski vel Grajewski, Przemysław; Tracz-Tryniecki, Marek, eds. (2016). Magna Carta: A Central European Perspective of Our Common Heritage of Freedom. Rutledge. p. xvi. ISBN 1317278593.

Britain in its history proposed many pioneering documents - not only Magna Carta, 1215 but those such as the Provisions of Oxford 1258, the Petition of Right 1628, the Bill of Rights 1689, and the Claim of Right 1689

- "From legal document to public myth: Magna Carta in the 17th century". The British Library. Retrieved 2017-10-16; "Magna Carta: Magna Carta in the 17th Century". The Society of Antiquaries of London. Archived from the original on 2018-09-25. Retrieved 2017-10-16.

- Maier, Pauline (1997). American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. New York: Knopf. pp. 126–28. ISBN 0-679-45492-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution. Penn State Press. ISBN 0271040130.

- Schwartz, Bernard (1992). The Great Rights of Mankind: A History of the American Bill of Rights. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780945612285.

- Conley, Patrick T.; States, U. S. Constitution Council of the Thirteen Original (1992). The Bill of Rights and the States: The Colonial and Revolutionary Origins of American Liberties. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 13–15. ISBN 9780945612292.

- Montoya, Maria; Belmonte, Laura A.; Guarneri, Carl J.; Hackel, Steven; Hartigan-O'Connor, Ellen (2016). Global Americans: A History of the United States. Cengage Learning. p. 116. ISBN 9780618833108.

- Hugh Starkey, Professor of Citizenship and Human Rights Education at UCL Institute of Education, London. "Magna Carta and Human rights legislation". British Library. Retrieved 22 November 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Abbott, Lewis F. Defending Liberty: The Case for a New Bill of Rights (ISR Business & the political-legal environment studies) Kindle Edition, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-10. Retrieved 2013-06-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Anderson, Deb (21 September 2010). "Does Australia need a bill of rights?". The Age. Melbourne.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2014-10-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-13. Retrieved 2014-10-26.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Howard opposes Bill of Rights". PerthNow. The Sunday Times. 2009-08-27. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Howard, John (2009-08-27). "2009 Menzies Lecture by John Howard (full text)". The Australian. News Limited. Archived from the original on 2009-08-30. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2008 (Vic).

- Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT).

- "Human Rights Act 2019". legislation.qld.gov.au. Queensland Government. 7 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Potter v Minahan [1908] HCA 63, (1908) 7 CLR 277, High Court (Australia).

- "Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania - 1776". Duquesne University. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bills of rights. |