War of the Peters

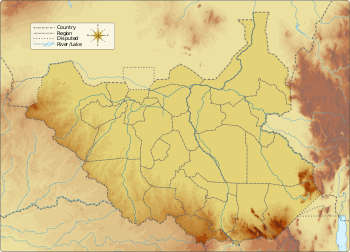

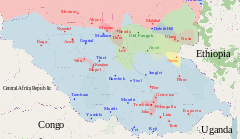

The War of the Peters[1][2] was a conflict primarily fought between the forces of Peter Par Jiek and Peter Gadet from June 2000 to August 2001 in Unity State, Sudan. Though both were leaders of local branches of larger rebel groups that were involved in the Second Sudanese Civil War (the SPDF and SPLA, respectively), the confrontation between the two commanders was essentially a private war. As Par and Gadet battled each other, the Sudanese government exploited the inter-rebel conflict as part of a divide and rule-strategy, aimed at weakening the rebellion at large and allowing for the extraction of valuable oil in Unity State. In the end, Gadet and Par reconciled when their respective superiors agreed to merge the SPDF and SPLA.

Background

Following its independence in 1956, the Sudan had suffered from numerous internal conflicts over political, ethnic, economic, and religious issues.[3] In 1983, revolutionaries and separatists from the country's marginalized south launched an uprising against the government which was traditionally dominated by elites from the north. The Second Sudanese Civil War had begun, and fighting spread across southern, eastern and western Sudan. The most prominent southern rebel group was the "Sudan People's Liberation Army" (SPLA) under the leadership of John Garang.[4] As the war escalated and spread, the SPLA grew increasingly powerful and overran much of southern Sudan.[5] Despite these successes, the SPLA faced major internal and external opposition. Many southern Sudanese outright opposed the group for a variety of reasons, and instead sided with the government or set up rival insurgent movements. In addition, Garang's leadership style caused tensions within the SPLA. He was charismatic, and a capable military commander, but also brutal and autocratic, suppressing and even executing critics.[6]

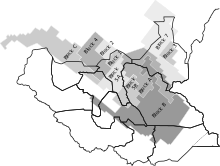

Two prominent SPLA commanders, Riek Machar and Lam Akol, attempted to overthrow Garang in an unsuccessful coup in 1991. The SPLA consequently split into warring factions, and the Sudanese government exploited this by employing a divide and rule strategy. It occasionally supported Machar's group (SPLA-United) so that it could fight against and weaken Garang's faction (SPLA-Mainstream).[7] In the next decade, alliances and militias formed and broke up again, while warlords carved out their own domains.[8] The Sudanese government increasingly focused on clearing areas in the south for oil extraction instead of winning the war, as it was in desperate need of cash.[9] As time went on, oil money became crucial for the Sudanese war effort.[10] One of the centers of oil production was Unity State, also known as Western Upper Nile. To secure the oil wells and pipelines and open land for oil extraction, the government often employed southern militias. These paramilitaries knew the terrain, were more expendable than Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) units, and allowed the government to frame the civil war as anarchic tribal infighting to deflect criticism of its own governance.[11]

The most prominent pro-government paramilitary group of southern Sudan was the SSDF. The SSDF was an umbrella organization for several armed factions, including Machar's loyalists and the troops of warlords like ex-Anyanya II leader Paulino Matip Nhial. It proved to be unstable and affected by internal rivalries, and gradually broke apart.[12] Different SSDF factions already fought each other in 1997 and 1998,[13][14] and the government allowed it to happen as it mistrusted most of the SSDF anyway.[13] The combat between the pro-government militias was fuelled by a desire of the warlords to control the oil-rich areas and thereby increase their revenue. Matip managed to oust Machar's followers and other rivals from the valuable region around Bentiu, drawing the latter's ire.[13][15] At the same time, the regime intensified efforts to take full control of the Block 5A oilfields in Unity State. These were held by Machar's forces, and he protested that the oil fields should remain under his control. The government responded by launching a campaign to drive away civilians and Machar's troops from drilling locations in Block 5A such as Thar Jath. Spearheaded by the SAF, northern militias, and Matip's force, entire tracts of land were depopulated.[16] In response, Machar's local loyalists under Tito Biel and Peter Par Jiek aligned with the SPLA and counterattacked.[17] A chaotic and brutal campaign ensued, as the military and numerous militias fought over control of the oil fields.[18][19]

In September 1999, most of Matip's militia revolted under Peter Gadet, as they were upset how the government was using local Nuer militias (like themselves) against other Nuer,[lower-alpha 1] while excluding them from the oil revenues.[21][22] This was a major setback for the government. Gadet was a highly competent commander,[23] and quickly captured the arms depot at Makien military base. He subsequently unified his force with the militias of other regional warlords such as Biel and Par to form the "Upper Nile Provisional United Military Command Council".[21] The rebel alliance proceeded to capture several important oil wells,[24] and the towns of Buoth, Rier, and Tan near Bentiu.[10]

The insurgents consequently agreed to split Unity State. Gadet and Par were assigned territories mostly in accordance to the ethnic groups which supported them: Gadet, an ethnic Bul Nuer, got Mayom and Wangkei (inhabited by Bul Nuer), while Par, a Dok Nuer, was granted Bentiu, Thar Jath, Leer, and Adok (territory of the Dok, Jikany, Jagei, and Leek Nuer).[25] The "Upper Nile Provisional United Military Command Council" alliance was quite successful, and the united forces of Gadet and Par defeated the SAF and Matip's militia in several battles. This adversely affected government control over Unity State, and reduced local oil production.[26] The situation changed once again in February 2000, when Machar openly broke with the government, fully left the SSDF, and founded the SPDF rebel group.[27] This development resulted in new tensions among the insurgents of Unity State. Machar loyalists like Par and Biel joined the SPDF, while Gadet had officially sided with SPLA-Mainstream – Machar's declared enemy.[28][lower-alpha 2] Limited clashes between Gadet and some Machar loyalists, though not between Gadet and Par, broke out soon after.[29] Despite the tensions and opposing political alignments, cooperation mostly continued until the Sudanese government launched another major offensive in Unity State in April 2000. This offensive pushed the rebel alliance to the breaking point. Old rivalries came to the fore, fuelled by the government's divide and rule strategy.[30]

History

Start of the conflict

The cooperation between Peter Par and Peter Gadet broke down in June–July 2000, as their militias began to fight each other. Who was responsible for the outbreak of hostilities is unknown, as both sides blamed each other.[1] The SPDF stated that its forces were attacked by Gadet loyalists "for no reason" in Nimne on 26 June 2000.[1] The SPLA argued that Par had executed 22 fighters loyal to Gadet in December 1999 and June 2000, and forged an alliance with the Sudanese government. This had allegedly forced the SPLA to act.[1] Tribal tensions between Dok and Bul Nuer may have contributed to the conflict. At least some locals framed the Par-Gadet fighting as Dok-Bul tribal war.[20]

In any case, Gadet launched a surprise attack on Nimne on 26 June or 7 July,[31] resulting in open war. The conflict subsequently became known as "War of the Peters".[1] As Par and Gadet clashed with each other, the Sudanese government eagerly exploited the situation. It provided ammunition to Par as long as he fought against the SPLA and left pro-government troops alone.[30] Most of the SPDF officially denied the reports of government support: Machar publicly claimed that the ammunition had come from secret stockpiles, and another SPDF commander stated that they had bought it from Baggara tribesmen. Taban Deng Gai admitted that Par had received one arms shipment from the government "to survive".[32] In fact, cooperation between Par and the government increased in intensity. Matip's SSDF militia began to openly fight alongside Par's men,[33] and the latter also guarded government installations, especially the oil extraction facilities of Thar Jath in Block 5A.[34] The SPDF even protected the road to Thar Jath, allowing Lundin Petroleum to access a new drilling site in Block 5A.[35][36] Regardless, Par officially remained in opposition to the government.[29]

Escalation and conclusion

Between July and August 2000, Par joined forces with Matip's militia and attacked Gadet's forces in the area between Nimne and Nhialdiu. They gradually pushed the SPLA westward, attacking Wicok, Buoth, Boaw, and Koch in succession. Most of Gadet's troops were forced to flee across the Jur River, and only Buoth remained under SPLA control.[37] At the same time, Gadet was resupplied by the SPLA central command,[38] and recruited new troops, including at least 400 child soldiers.[39] He launched a counter-offensive in August 2000, and had retaken most of the lost ground by late September.[38] When they captured Koch, Gadet's men killed two health workers and stole the local clinic's medical supplies.[40] Meanwhile, tensions grew between Par and SPDF co-commander Tito Biel. To avoid war between them, Machar sent Biel to Maiwut County where he was supposed to rally Jikany Nuer to the SPDF's cause.[29]

The War of the Peters was brutal, led to enormous destruction, and displaced up to 60,000 people.[41][42] Many civilians fled to Bahr el Ghazal,[39] and although hunger and disease spread among the refugees,[43] most subsequently chose to stay as their old homes had been destroyed.[39] Both sides used scorched earth tactics,[44] and completely destroyed many settlements, including Nhialdiu.[41] Schools were also targeted,[45] and the militants killed, raped, and abducted many civilians.[44] The war also increased lower-level tribal conflicts between the Bul and Dok Nuer. The region became too dangerous for the delivery of humanitarian aid, worsening the civilians' suffering.[15] The Sudanese government and the oil companies benefitted greatly from the War of the Peters, as the inter-rebel fighting allowed them to boost the oil extraction.[46] In turn, the government was able to increase its defense expenditure and acquire new weaponry for the civil war.[47]

Gadet's troops attacked the United Nations relief hub of Nyal inside SPDF territory in February 2001. This almost resulted in a further escalation, as the attack was regarded as breach of an earlier peace agreement between Nuer and Dinka militias that was still partially in effect.[44] In addition, this raid caused tensions in Par's militia. Nyal was traditionally Nyuong Nuer territory, and the Nyuong fighters of Par's force believed that the Dok and Bul were spreading their destructive tribal conflict to Nyuong lands. As a result, a shootout between Nyuong and Dok militants erupted at Par's base in Nyal in early May 2001.[48] Gadet launched another major raid against Bentiu, a center of the regional oil infrastructure, on 8 June 2001. The SPLA-Mainstream used the occasion to warn oil companies to withdraw from Sudan, threatening that they were regarded as military targets by the rebels.[10] The War of the Peters continued until August 2001,[44] when Par and Gadet agreed to a ceasefire. A few months later, Machar came to an understanding with the SPLA leadership and agreed to merge the SPDF with SPLA-Mainstream, whereupon Par and Gadet signed a final peace agreement in Koch in February 2002. Par and his faction joined the SPLA,[49][50] and he and Gadet formally merged their armies.[29] In contrast, Tito Biel was opposed to joining SPLA-Mainstream, and defected to Matip's militia.[29]

Aftermath

The restoration of a rebel alliance in Unity State resulted in growing insecurity in the Block 5A oilfield. Lundin Petroleum suspended opeations at Thar Jath, forcing the government to launch new costly offensives in Unity State in 2002.[47][51] The offensives proved to be successful enough to serve as a model for other military operations.[52] Fighting continued, and allegiances continued to shift in Unity State. In particular, Gadet would play out the SPLA and the government against each other to gain power,[23] and eventually fully defected back to the pro-government forces.[29] The Second Sudanese Civil War ended in 2005, and South Sudan became independent in 2011.[53] Many issues of the conflict remained unresolved, and most southern warlords such as Gadet continued to maintain their private armies. The warlords occasionally revolted,[23][54] and South Sudan remained politically unstable.[54] The country descended into another civil war in late 2013.[55] Par and Gadet died during this conflict: The former was killed fighting against his former superior, Machar,[56] while the latter died after a heart attack.[57]

Notes

- Matip's militia, including Gadet and his defectors, were Bul Nuer. Their opponents were largely recruited from Dok and Riek Nuer. The degree to which these tribal identities were related to the conflict is unclear. At times, clashes appeared to be fuelled by rivalries between the Nuer subgroups, but there was also much inter-Nuer cooperation as well as ethnically mixed Nuer militias.[20]

- Gadet had initially joined the South Sudan Liberation Movement in November 1999, but switched to the SPLA when Machar returned to the south in 2000.[29]

References

- Rone 2003, p. 351.

- Philippe 2006, p. 67.

- Martell 2018, pp. 5, 145.

- Martell 2018, pp. 102–114.

- Martell 2018, pp. 120–123.

- Martell 2018, pp. 129–132.

- Martell 2018, pp. 132–133.

- Martell 2018, pp. 133–137.

- Martell 2018, pp. 123–128.

- Khalid 2010, p. 348.

- Rone 2003, pp. 72–73.

- LeRiche & Arnold 2013, p. 99.

- Rone 2003, p. 72.

- Harker 2000, p. 55.

- Philippe 2006, pp. 66–67.

- Rone 2003, pp. 73–74.

- Harker 2000, p. 57.

- Harker 2000, pp. 55–57.

- Rone 2003, pp. 74–75.

- Johnson 2009, pp. 44–45.

- Rone 2003, pp. 75–76.

- LeRiche & Arnold 2013, p. 101.

- LeBrun 2011, p. 4.

- Lobban 2010, p. 109.

- Rone 2003, p. 346.

- Rone 2003, pp. 75–76, 342–343.

- Rone 2003, pp. 76, 358–360.

- Rone 2003, p. 76.

- Johnson 2009, p. 44.

- Rone 2003, pp. 76–77.

- Rone 2003, pp. 351–352.

- Rone 2003, p. 353.

- Rone 2003, pp. 352–353.

- Rone 2003, pp. 77, 386.

- Rone 2003, p. 364.

- Lobban 2010, p. 114.

- Rone 2003, pp. 358–359.

- Rone 2003, pp. 359-360.

- Rone 2003, pp. 361–362.

- Rone 2003, p. 360.

- Rone 2003, pp. 358–360.

- Nyaba 2002, p. 116.

- Rone 2003, pp. 362-363.

- Rone 2003, p. 77.

- Rone 2003, p. 361.

- Rone 2003, pp. 353, 354.

- Lobban 2010, pp. 114–115.

- Johnson 2009, p. 45.

- Rone 2003, pp. 364, 372–373.

- "Focus on oil-related clashes in western Upper Nile". IRIN. 28 February 2002. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- Rone 2003, pp. 77–78, 364–365.

- Rone 2003, pp. 78–79.

- Martell 2018, p. x.

- Martell 2018, pp. 187–189.

- Martell 2018, p. 207.

- "Machar rebels kill two SPLA Generals". The Insider. 11 April 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- "South Sudan's Peter Gatdet dies in Khartoum". Sudan Tribune. 16 April 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

Works cited

- Harker, John (2000). Human Security in Sudan: The Report of a Canadian Assessment Mission (PDF). Ottawa: Global Affairs Canada.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson, Douglas H. (2009). "The Nuer Civil Wars". In Günther Schlee; Elizabeth E. Watson (eds.). Changing Identifications and Alliances in North-east Africa: Volume II: Sudan, Uganda, and the Ethiopia-Sudan borderlands. New York City; Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 31–48. ISBN 978-1-84545-604-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khalid, Mansour (2010) [1st pub. 2003]. War & Peace In The Sudan. London; New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7103-0663-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rone, Jemera (2003). Sudan, oil, and human rights. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1-56432-291-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- LeBrun, Emile, ed. (November 2011). "Fighting for spoils. Armed insurgencies in Greater Upper Nile" (PDF). HSBA Issue Brief. Geneva: Small Arms Survey (18).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- LeRiche, Matthew; Arnold, Matthew (2013). South Sudan: From Revolution to Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933340-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lobban, Richard Andrew (2010). Global Security Watch - Sudan. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-35332-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martell, Peter (2018). First Raise a Flag. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1849049597.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nyaba, Peter Adwok (2002). "The Impact of Oil and Gas Development on the Local and National Economy, Environment and Society in the Sudan". Self-determination, The Oil and Gas Sector and Religion and the State in the Sudan. Ottawa: The Sudan Peace-Building Programme African Renaissance Institute (ARI); Relationships Foundation International (RFI). pp. 101–131.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Philippe, Catherine (2006). Southern Sudan: The Challenges of Peace. Montreal: McGill University. ISBN 978-0-494-32546-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)