Lemnian language

The Lemnian language was spoken on the island of Lemnos in the 6th century BC. It is mainly attested by an inscription found on a funerary stele, termed the Lemnos stele, discovered in 1885 near Kaminia. Fragments of inscriptions on local pottery show that it was spoken there by a community.[2] In 2009, a newly discovered inscription was reported from the site of Hephaistia, the principal ancient city of Lemnos.[3] Lemnian is largely accepted as being closely related to Etruscan.[4][5][6][7] After the Athenians conquered the island in the latter half of the 6th century BC, Lemnian was replaced by Attic Greek.

| Lemnian | |

|---|---|

| Region | Lemnos |

| Extinct | attested 6th century BC |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xle |

xle | |

| Glottolog | lemn1237[1] |

Location of Lemnos | |

Writing system

The Lemnian inscriptions are in Western Greek alphabet, also called "red alphabet". The red type is found in most parts of central and northern mainland Greece (Thessaly, Boeotia and most of the Peloponnese), as well as the island of Euboea, and in colonies associated with these places, including most colonies in Italy. [8] The alphabet used for Lemnian inscriptions is similar to an archaic variant used to write the Etruscan language in southern Etruria.[9]

Classification

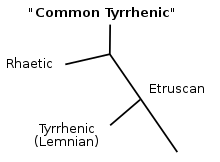

A relationship between Lemnian and Etruscan, as a Tyrsenian language family, has been proposed by German linguist Helmut Rix due to close connections in vocabulary and grammar. For example,

- both Etruscan and Lemnian share two unique dative cases, type-I *-si and type-II *-ale, shown both on the Lemnos Stele (Hulaie-ši "for Hulaie", Φukiasi-ale "for the Phocaean") and in inscriptions written in Etruscan (aule-si - "To Aule" - on the Cippus Perusinus as well as the inscription mi mulu Laris-ale Velχaina-si, meaning "I was blessed for Laris Velchaina").

- They also share the genitive in *-s and a simple past tense in *-a-i (Etruscan -⟨e⟩ as in ame "was" (< *amai); Lemnian -⟨ai⟩ as in šivai, meaning "lived").

Rix's Tyrsenian family has been confirmed by Stefan Schumacher,[11][12] [13][14] Carlo De Simone[15] and Simona Marchesini.[10] Common features between Lemnian, Etruscan, and Rhaetic have been found in morphology, phonology, and syntax. On the other hand, few lexical correspondences are documented, at least partly due to the scanty number of Rhaetian and Lemnian texts.[16][17]

The Tyrsenian family, or Common Tyrrhenic, in this case is often considered to be Paleo-European and to predate the arrival of Indo-European languages in southern Europe.[18]

The Lemnian language could have arrived in the Aegean Sea during the Late Bronze Age, when Mycenaean rulers recruited groups of mercenaries from Sicily, Sardinia and various parts of the Italian peninsula.[19]

Vowels

Like Etruscan, the Lemnian language appears to have had a four-vowel system, consisting of "i", "e", "a" and "u". Other languages in the neighbourhood of the Lemnian area, namely Hittite and Akkadian, had similar four-vowel systems, suggesting early areal influence.

Lemnos Stele

The stele was found built into a church wall in Kaminia and is now at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. The 6th century date is based on the fact that in 510 BC the Athenian Miltiades invaded Lemnos and Hellenized it.[20] The stele bears a low-relief bust of a man and is inscribed in an alphabet similar to the western ("Chalcidian") Greek alphabet. The inscription is in Boustrophedon style, and has been transliterated but had not been successfully translated until serious linguistic analysis based on comparisons with Etruscan, combined with breakthroughs in Etruscan's own translation started to yield fruit.

The inscription consists of 198 characters forming 33 to 40 words, word separation sometimes indicated with one to three dots. The text consists of three parts, two written vertically and one horizontally. Comprehensible is the phrase aviš sialχviš ("aged sixty", B.3), reminiscent of Etruscan avils maχs śealχisc ("and aged sixty-five").

Transcription:

- front:

- A.1. hulaieš:naφuθ:šiaši

- A.2. maraš:mav

- A.3. sialχveiš:aviš

- A.4. evisθu:šerunaiθ

- A.5. šivai

- A.6. aker:tavaršiu

- A.7. vanalasial:šerunai:murinail

- side:

- B.1. hulaieši:φukiasiale:šerunaiθ:evisθu:tuveruna

- B.2. rum:haraliu:šivai:eptešiu:arai:tiš:φuke

- B.3. šivai:aviš:sialχviš:marašm:aviš:aumai

Hephaistia inscription

Another Lemnian inscription has been found during excavations at Hephaistia on the island of Lemnos.[21] The inscription consists of 26 letters arranged in two lines of boustrophedonic script.

Transcription:

- upper line (left to right):

- hktaonosi:heloke

- lower line (right to left):

- soromš:aslaš

See also

- Aegean languages

- Tyrsenian language family

Notes

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Lemnian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Bonfante, p. 11.

- de Simone

- "Origins of the Etruscans". Etruskisch.de. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- "Lemnian". Lila.sns.it. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- "Origins of the Etruscans". Etruskisch.de. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- "The Lemnos Stele". Carolandray.plus.com. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

- Woodard, Roger D. (2010). "Phoinikeia grammata: an alphabet for the Greek language". In Bakker, Egbert J. (ed.). A companion to the ancient Greek language. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 26-46.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marchesini, Simona (2009). Le lingue frammentarie dell'Italia antica (in Italian) (1st ed.). Milan: Hoepli. pp. 105–106.

- Carlo de Simone, Simona Marchesini (Eds), La lamina di Demlfeld [= Mediterranea. Quaderni annuali dell'Istituto di Studi sulle Civiltà italiche e del Mediterraneo antico del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. Supplemento 8], Pisa – Roma: 2013.

- Schumacher, Stefan (1994) Studi Etruschi in Neufunde ‘raetischer’ Inschriften Vol. 59 pp. 307-320 (German)

- Schumacher, Stefan (1994) Neue ‘raetische’ Inschriften aus dem Vinschgau in Der Schlern Vol. 68 pp. 295-298 (German)

- Schumacher, Stefan (1999) Die Raetischen Inschriften: Gegenwärtiger Forschungsstand, spezifische Probleme und Zukunfstaussichten in I Reti / Die Räter, Atti del simposio 23-25 settembre 1993, Castello di Stenico, Trento, Archeologia delle Alpi, a cura di G. Ciurletti - F. Marzatico Archaoalp pp. 334-369 (German)

- Schumacher, Stefan (2004) Die Raetischen Inschriften. Geschichte und heutiger Stand der Forschung Archaeolingua. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft. (German)

- de Simone Carlo (2009) La nuova iscrizione tirsenica di Efestia in Aglaia Archontidou, Carlo de Simone, Emanuele Greco (Eds.), Gli scavi di Efestia e la nuova iscrizione ‘tirsenica’, TRIPODES 11, 2009, pp. 3-58. Vol. 11 pp. 3-58 (Italian)

- Simona Marchesini (translation by Melanie Rockenhaus) (2013). "Raetic (languages)". Mnamon - Ancient Writing Systems in the Mediterranean. Scuola Normale Superiore. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Kluge Sindy, Salomon Corinna, Schumacher Stefan (2013–2018). "Raetica". Thesaurus Inscriptionum Raeticarum. Department of Linguistics, University of Vienna. Retrieved 26 July 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: date format (link)

- Mellaart, James (1975), "The Neolithic of the Near East" (Thames and Hudson)

- De Ligt, Luuk. "An Eteocretan' inscription from Praisos and the homeland of the Sea Peoples" (PDF). talanta.nl. ALANTA XL-XLI (2008-2009), 151-172.

- Herodotus, 6.136-140

- Carlo de Simone, La Nuova Iscrizione ‘Tirsenica’ di Lemnos (Efestia, teatro): considerazioni generali, Rasenna: Journal of the Center for Etruscan Studies: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 1, 2011. (Italian)

References

- Bonfante, Larissa (1990). Etruscan. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07118-2.

- de Simone, Carlo (2009). "La nuova iscrizione tirsenica di Efestia". Tripodes. 11. pp. 3–58.

- Steinbauer, Dieter H. (1999). Neues Handbuch des Etruskischen. St. Katharinen: Scripta Mercaturae Verlag.