Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight (/waɪt/) is a county and the largest and second-most populous island in England. It is in the English Channel, between 2 and 5 miles off the coast of Hampshire, separated by the Solent. The island has resorts that have been holiday destinations since Victorian times, and is known for its mild climate, coastal scenery, and verdant landscape of fields, downland and chines. The island is designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.

| Isle of Wight | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceremonial county | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Motto: "All this beauty is of God" | |||||

| |||||

| Coordinates: 50°40′N 1°16′W | |||||

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom | ||||

| Constituent country | England | ||||

| Region | South East | ||||

| Established | 1890 | ||||

| Preceded by | Hampshire | ||||

| Ceremonial county | |||||

| Lord Lieutenant | Susan Sheldon[2] | ||||

| High Sheriff | Mrs Caroline Peel[3] (2020/21) | ||||

| Area | 384 km2 (148 sq mi) | ||||

| • Ranked | 46th of 48 | ||||

| Population (mid-2019 est.) | 141,538 | ||||

| • Ranked | 46th of 48 | ||||

| Density | 372/km2 (960/sq mi) | ||||

| Ethnicity | 97.3% White, 1.1% Asian, 0.2% Black, 0.1% Other, 1.2% Mixed[4] | ||||

| Unitary authority | |||||

| Council | Isle of Wight Council | ||||

| Executive | Conservative | ||||

| Admin HQ | Newport | ||||

| Area | 380.2 km2 (146.8 sq mi) | ||||

| • Ranked | 103rd of 326 | ||||

| Population | 141,771 | ||||

| • Ranked | 153rd of 326 | ||||

| Density | 372/km2 (960/sq mi) | ||||

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-IOW | ||||

| ONS code | 00MW | ||||

| GSS code | E06000046 | ||||

| NUTS | UKJ34 | ||||

| Website | https://www.iow.gov.uk | ||||

| Member of Parliament | Bob Seely | ||||

| Police | Hampshire Constabulary | ||||

| Time zone | Greenwich Mean Time (UTC) | ||||

| • Summer (DST) | British Summer Time (UTC+1) | ||||

The island has been home to the poets Algernon Charles Swinburne and Alfred, Lord Tennyson and to Queen Victoria, who built her much-loved summer residence and final home Osborne House at East Cowes. It has a maritime and industrial tradition including boat-building, sail-making, the manufacture of flying boats, the hovercraft, and Britain's space rockets. The island hosts annual music festivals including the Isle of Wight Festival, which in 1970 was the largest rock music event ever held.[5] It has well-conserved wildlife and some of the richest cliffs and quarries for dinosaur fossils in Europe.

The isle was owned by a Norman family until 1293 and was earlier a kingdom in its own right, Wihtwara.[6] In common with the Crown dependencies, the British Crown was then represented on the island by the Governor of the Isle of Wight[n 1] until 1995. The island has played an important part in the defence of the ports of Southampton and Portsmouth, and been near the front-line of conflicts through the ages, including the Spanish Armada and the Battle of Britain. Rural for most of its history, its Victorian fashionability and the growing affordability of holidays led to significant urban development during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Historically part of Hampshire, the island became a separate administrative county in 1890. It continued to share the Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire until 1974, when it was made its own ceremonial county. Apart from a shared police force, and the island's Anglican churches belonging to the Diocese of Portsmouth (originally Winchester), there is now no administrative link with Hampshire; although a combined local authority with Portsmouth and Southampton was considered,[7] this is now unlikely to proceed.[8]

The quickest public transport link to the mainland is the hovercraft from Ryde to Southsea; three vehicle ferry and two catamaran services cross the Solent to Southampton, Lymington and Portsmouth.

History

Palaeolithic Isle of Wight

During Pleistocene glacial periods, sea levels were lower and the present day Solent was part of the valley of the Solent River. The river flowed eastward from Dorset, following the course of the modern Solent strait, before travelling south and southwest towards the major Channel River system.

The earliest evidence of archaic human presence on what is now the Isle of Wight is found at Priory Bay. Here more than 300 acheulean handaxes have been recovered from the beach and cliff slopes, originating from a sequence of Pleistocene gravels dating approximately to MIS 11 (424,000-374,000 years ago).[9]

A Mousterian flint assemblage, consisting of 50 handaxes and debitage has been recovered from Great Pan Farm near Newport. Possibly dating to MIS 7 (c.240,000 years ago), these tools are associated with Neanderthal occupation.

Mesolithic Isle of Wight

A submerged escarpment 11m below sea level off Bouldnor Cliff on the island's northwest coastline is home to an internationally significant mesolithic archaeological site. The site has yielded evidence of seasonal occupation by mesolithic hunter-gatherers dating to c.8000 years BP. Finds include flint tools, burnt flint, worked timbers, wooden platforms and pits. The worked wood shows evidence of the splitting of large planks from oak trunks, interpreted as being intended for use as dug-out canoes. DNA analysis of sediments at the site yielded wheat DNA, not found in Britain until the Neolithic 2000 years after the occupation at Bouldnor Cliff. It has been suggested this is evidence of wide-reaching trade in mesolithic Europe, however the contemporaneity of the wheat with the Mesolithic occupation has been contested. When hunter-gatherers used the site it was located on a river bank surrounded by wetland and woodland.[10] As sea levels rose throughout the Holocene the river valley slowly flooded, submerging the site.

Evidence of mesolithic occupation on the island is generally found along the river valleys, particularly along the north of the Island, and in the former catchment of the western Yar. Further key sites are found at Newtown Creek, Werrar and Wootton-Quarr.

Neolithic Isle of Wight

Neolithic occupation on the Isle of Wight is primarily attested to by flint tools and monuments. Unlike the previous mesolithic hunter-gatherer population Neolithic communities on the Isle of Wight were based on farming and linked to a wide-scale migration of Neolithic populations from France and northwest Europe to Britain c.6000 years ago.

The Isle of Wight's most visible Neolithic site is the Longstone at Mottistone, the remains of a long-barrow originally constructed with two standing stones at the entrance. Only one stone remains standing today. A Neolithic mortuary enclosure has been identified on Tennyson Down near Freshwater.

Bronze and Iron Age Isle of Wight

Bronze Age Britain had large reserves of tin in the areas of Cornwall and Devon and tin is necessary to smelt bronze. At that time the sea level was much lower and carts of tin were brought across the Solent at low tide[11][12] for export, possibly on the Ferriby Boats. Anthony Snodgrass[13][14] suggests that a shortage of tin, as a part of the Bronze Age Collapse and trade disruptions in the Mediterranean around 1300 BC, forced metalworkers to seek an alternative to bronze. During Iron Age Britain, the Late Iron Age, the Isle of Wight would appear to have been occupied by the Celtic tribe, the Durotriges – as attested by finds of their coins, for example, the South Wight Hoard,[15][16] and the Shalfleet Hoard.[17] South eastern Britain experienced significant immigration that is reflected in the genetic makeup of the current residents.[18] As the Iron Age began the value of tin likely dropped sharply and this likely greatly changed the economy of the Isle of Wight. Trade however continued as evidenced by the remarkable local abundance of European Iron Age coins.[19][20]

Roman Isle of Wight

Julius Caesar reported that the Belgae took the Isle of Wight in about 85 BC,[21] and recognised the culture of this general region as "Belgic", but made no reference to Vectis.[22] The Roman historian Suetonius mentions that the island was captured by the commander Vespasian. The Romans built no towns on the island, but the remains of at least seven Roman villas have been found, indicating the prosperity of local agriculture.[23] First-century exports were principally hides, slaves, hunting dogs, grain, cattle, silver, gold, and iron.[22]

Early Medieval period

Starting in AD 449 (according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicles) the 5th and 6th centuries saw groups of Germanic speaking peoples from Northern Europe crossing the English Channel and setting up home.[24] Bede's (731) Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum[25] identifies three separate groups of invaders: of these, the Jutes from Denmark settled the Isle of Wight and Kent. From then onwards, there are indications that the island had wide trading links, with a port at Bouldnor,[26][27][28] evidence of Bronze Age tin trading,[12] and finds of Late Iron Age coins.[29]

During the Dark Ages the island was settled by Jutes as the pagan kingdom of Wihtwara under King Arwald. In 685 it was invaded by Caedwalla, who tried to replace the inhabitants with his own followers. In 686 Arwald was defeated and the island became the last part of English lands to be converted to Christianity,[30][31][32] added to Wessex and then becoming part of England under King Alfred the Great, included within the shire of Hampshire.

It suffered especially from Viking raids,[33] and was often used as a winter base by Viking raiders when they were unable to reach Normandy.[34] Later, both Earl Tostig and his brother Harold Godwinson (who became King Harold II) held manors on the island.[35][36]

High Medieval period

The Norman Conquest of 1066 created the position of Lord of the Isle of Wight; the island was given by William the Conqueror to his kinsman William FitzOsbern. Carisbrooke Priory and the fort of Carisbrooke Castle were then founded. Allegiance was sworn to FitzOsbern rather than the king; the Lordship was subsequently granted to the de Redvers family by Henry I, after his succession in 1100.

For nearly 200 years the island was a semi-independent feudal fiefdom, with the de Redvers family ruling from Carisbrooke. The final private owner was the Countess Isabella de Fortibus, who, on her deathbed in 1293, was persuaded to sell it to Edward I. Thereafter the island was under control of the English Crown[37] and its Lordship a royal appointment.

Late Medieval period

The island continued to be attacked from the continent: it was raided in 1374 by the fleet of Castile,[38] and in 1377 by French raiders who burned several towns, including Newtown, and laid siege to Carisbrooke Castle before they were defeated.

Early modern period

Under Henry VIII, who developed the Royal Navy and its Portsmouth base, the island was fortified at Yarmouth, Cowes, East Cowes, and Sandown.

The French invasion on 21 July 1545 (famous for the sinking of the Mary Rose on the 19th) was repulsed by local militia.[39]

During the English Civil War, King Charles fled to the Isle of Wight, believing he would receive sympathy from the governor Robert Hammond, but Hammond imprisoned the king in Carisbrooke Castle.[40]

During the Seven Years' War, the island was used as a staging post for British troops departing on expeditions against the French coast, such as the Raid on Rochefort. During 1759, with a planned French invasion imminent, a large force of soldiers was stationed there. The French called off their invasion following the Battle of Quiberon Bay.[41]

Modern history

In the 1860s, what remains in real terms the most expensive ever government spending project saw fortifications built on the island and in the Solent, as well as elsewhere along the south coast, including the Palmerston Forts, The Needles Batteries and Fort Victoria, because of fears about possible French invasion.[42]

The future Queen Victoria spent childhood holidays on the island and became fond of it. When queen she made Osborne House her winter home, and so the island became a fashionable holiday resort, including for Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Julia Margaret Cameron, and Charles Dickens (who wrote much of David Copperfield there), as well as the French painter Berthe Morisot and members of European royalty.[43]

Until the queen's example, the island had been rural, with most people employed in farming, fishing or boat-building. The boom in tourism, spurred by growing wealth and leisure time, and by Victoria's presence, led to significant urban development of the island's coastal resorts. As one report summarizes, "The Queen’s regular presence on the island helped put the Isle of Wight 'on the map' as a Victorian holiday and wellness destination ... and her former residence Osborne House is now one of the most visited attractions on the island[44] While on the island, the queen used a bathing machine that could be wheeled into the water on Osborne Beach; inside the small wooden hut she could undress and then bathe, without being visible to others. [45] Her machine had a changing room and a WC with plumbing. The refurbished machine is now displayed at the beach.[46][47]

On 14 January 1878, Alexander Graham Bell demonstrated an early version of the telephone to the queen,[48] placing calls to Cowes, Southampton and London. These were the first publicly-witnessed long distance telephone calls in the UK. The queen tried the device and considered the process to be "quite extraordinary" although the sound was "rather faint".[49] She later asked to buy the equipment that was used, but Bell offered to make "a set of telephones" specifically for her.[50][51]

The world's first radio station was set up by Marconi in 1897, during her reign, at the Needles Battery, at the western tip of the island.[52][53] A 168 foot high mast was erected near the Royal Needles Hotel, as part of an experiment of communicating with ships at sea. That location is now the site of the Marconi Monument.[54] In 1898 the first paid wireless telegram (called a "Marconigram") was sent from this station, and the island was for some time[55] the home of the National Wireless Museum, near Ryde.[56]

Queen Victoria died at Osborne House on 22 January 1901, aged 81.

During the Second World War the island was frequently bombed. With its proximity to German-occupied France, the island hosted observation stations and transmitters, as well as the RAF radar station at Ventnor. It was the starting-point for one of the earlier Operation Pluto pipelines to feed fuel to Europe after the Normandy landings.[57]

The Needles Battery was used to develop and test the Black Arrow and Black Knight space rockets, which were subsequently launched from Woomera, Australia.[58]

The Isle of Wight Festival was a very large rock festival that took place near Afton Down, West Wight in 1970, following two smaller concerts in 1968 and 1969. The 1970 show was notable both as one of the last public performances by Jimi Hendrix and for the number of attendees, reaching by some estimates 600,000.[59] The festival was revived in 2002 in a different format, and is now an annual event.[60]

Etymology

The oldest records that give a name for the Isle of Wight are from the Roman Empire: it was then called Vectis or Vecta in Latin, Iktis or Ouiktis in Greek. From the Anglo-Saxon period Latin Vecta, Old English Wiht and Old Welsh forms Gueid and Guith are recorded. In Domesday Book it is Wit; the modern Welsh name is Ynys Wyth (ynys = island). These are all variant forms of the same name, possibly Celtic in origin. It may mean "place of the division", because the island divides the two arms of the Solent.[61][62][63]

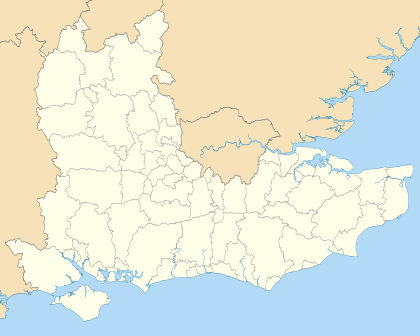

Geography

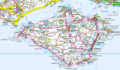

The Isle of Wight is situated between the Solent and the English Channel, is roughly rhomboid in shape, and covers an area of 150 sq mi (380 km2). Slightly more than half, mainly in the west, is designated as the Isle of Wight Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The island has 100 sq mi (258 km2) of farmland, 20 sq mi (52 km2) of developed areas, and 57 miles (92 km) of coastline. Its landscapes are diverse, leading to its oft-quoted description as "England in miniature". In June 2019 the whole island was designated a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, recognising the sustainable relationships between its residents and the local environment.[64]

West Wight is predominantly rural, with dramatic coastlines dominated by the chalk downland ridge, running across the whole island and ending in the Needles stacks. The southwestern quarter is commonly referred to as the Back of the Wight, and has a unique character. The highest point on the island is St Boniface Down in the south east, which at 791 feet (241 m) is a marilyn.[65] The most notable habitats on the rest of the island are probably the soft cliffs and sea ledges, which are scenic features, important for wildlife, and internationally protected.

The island has three principal rivers. The River Medina flows north into the Solent, the Eastern Yar flows roughly northeast to Bembridge Harbour, and the Western Yar flows the short distance from Freshwater Bay to a relatively large estuary at Yarmouth. Without human intervention the sea might well have split the island into three: at the west end where a bank of pebbles separates Freshwater Bay from the marshy backwaters of the Western Yar east of Freshwater, and at the east end where a thin strip of land separates Sandown Bay from the marshy Eastern Yar basin.

The Undercliff between St Catherine's Point and Bonchurch is the largest area of landslip morphology in western Europe.

The north coast is unusual in having four high tides each day, with a double high tide every twelve and a half hours. This arises because the western Solent is narrower than the eastern; the initial tide of water flowing from the west starts to ebb before the stronger flow around the south of the island returns through the eastern Solent to create a second high water.[56]

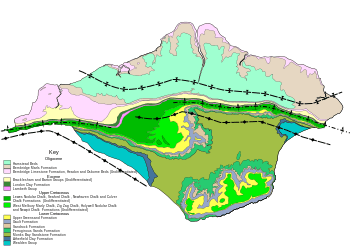

Geology

The Isle of Wight is made up of a variety of rock types dating from early Cretaceous (around 127 million years ago) to the middle of the Palaeogene (around 30 million years ago). The geological structure is dominated by a large monocline which causes a marked change in age of strata from the northern younger Tertiary beds to the older Cretaceous beds of the south. This gives rise to a dip of almost 90 degrees in the chalk beds, seen best at the Needles.

The northern half of the island is mainly composed of clays, with the southern half formed of the chalk of the central east–west downs, as well as Upper and Lower Greensands and Wealden strata.[66] These strata continue west from the island across the Solent into Dorset, forming the basin of Poole Harbour (Tertiary) and the Isle of Purbeck (Cretaceous) respectively. The chalky ridges of Wight and Purbeck were a single formation before they were breached by waters from the River Frome during the last ice age, forming the Solent and turning Wight into an island. The Needles, along with Old Harry Rocks on Purbeck, represent the edges of this breach.

All the rocks found on the island are sedimentary, such as limestones, mudstones and sandstones. They are rich in fossils; many can be seen exposed on beaches as the cliffs erode. Lignitic coal is present in small quantities within seams, and can be seen on the cliffs and shore at Whitecliff Bay. Fossilised molluscs have been found there, and also on the northern coast along with fossilised crocodiles, turtles and mammal bones; the youngest date back to around 30 million years ago.

The island is one of the most important areas in Europe for dinosaur fossils. The eroding cliffs often reveal previously hidden remains, particularly along the Back of the Wight.[67] Dinosaur bones and fossilised footprints can be seen in and on the rocks exposed around the island's beaches, especially at Yaverland and Compton Bay. As a result, the island has been nicknamed "Dinosaur Island" and Dinosaur Isle was established in 2001.

The area was affected by sea level changes during the repeated Quaternary glaciations. The island probably became separated from the mainland about 125,000 years ago, during the Ipswichian interglacial.[68]

Ordnance Survey map of the island

Ordnance Survey map of the island Geological map of the island

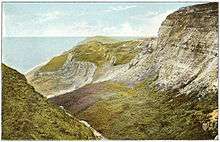

Geological map of the island Blackgang Chine, circa 1910

Blackgang Chine, circa 1910 A view of the Needles and Alum Bay

A view of the Needles and Alum Bay

Climate

Like the rest of the UK, the island has an oceanic climate, but is somewhat milder and sunnier, which makes it a holiday destination. It also has a longer growing season. Lower Ventnor and the neighbouring Undercliff have a particular microclimate, because of their sheltered position south of the downs. The island enjoys 1,800–2,100 hours of sunshine a year.[69] Some years have almost no snow in winter, and only a few days of hard frost.[70] The island is in Hardiness zone 9.[71]

| Climate data for Shanklin | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.0 (50.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

15.6 (60.1) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.5 (68.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.3 (52.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

13.9 (56.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.5 (49.1) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

7.8 (46.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 90.8 (3.57) |

65.5 (2.58) |

66.0 (2.60) |

53.4 (2.10) |

52.1 (2.05) |

46.3 (1.82) |

47.1 (1.85) |

54.6 (2.15) |

70.5 (2.78) |

115.0 (4.53) |

108.6 (4.28) |

101.0 (3.98) |

870.9 (34.29) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0) | 13.1 | 9.8 | 10.4 | 9.1 | 8.2 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 7.4 | 8.9 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 12.9 | 119.7 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 68.2 | 89.8 | 132.9 | 201.4 | 241.1 | 247.7 | 262.3 | 240.9 | 173.1 | 122.3 | 82.6 | 60.7 | 1,923 |

| Source: Met Office Climate Averages, Shanklin, 1981-2010 | |||||||||||||

Wildlife

The Isle of Wight is one of the few places in England where the red squirrel is still flourishing; no grey squirrels are to be found.[72] There are occasional sightings of wild deer, and there is a colony of wild goats on Ventnor's downs.[73][74][75][76] Protected species such as the dormouse and rare bats can be found. The Glanville fritillary butterfly's distribution in the United Kingdom is largely restricted to the edges of the island's crumbling cliffs.[77]

A competition in 2002 named the pyramidal orchid as the Isle of Wight's county flower.[78]

Politics

The island has a single Member of Parliament. The Isle of Wight constituency covers the entire island, with 138,300 permanent residents in 2011, being one of the most populated constituencies in the United Kingdom (more than 50% above the English average).[79] In 2011 following passage of the Parliamentary Voting System and Constituencies Act, the Sixth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies was to have changed this,[80] but this was deferred to no earlier than October 2018 by the Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013. Thus the single constituency remained for the 2015 and 2017 general elections. However, two separate East and West constituencies are proposed for the island under the 2018 review now under way.

The Isle of Wight is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county. Since the abolition of its two borough councils and restructuring of the Isle of Wight County Council into the new Isle of Wight Council in 1995, it has been administered by a single unitary authority.

Elections in the constituency have traditionally been a battle between the Conservatives and the Liberal Democrats. Andrew Turner of the Conservative Party gained the seat from Peter Brand of the Lib Dems at the 2001 general election. Since 2009, Turner was embroiled in controversy over his expenses, health, and relationships with colleagues, with local Conservatives having tried but failed to remove him in the runup to the 2015 general election.[81] He stood down prior to the 2017 snap general election, and the new Conservative Party candidate Bob Seely was elected with a majority of 21,069 votes.

At the Isle of Wight Council election of 2013, the Conservatives lost the majority which they had held since 2005 to the Island Independents, with Island Independent councillors holding 16 of the 40 seats, and a further five councillors sitting as independents outside the group.[82] The Conservatives regained control, winning 25 seats, at the 2017 local election.[83]

There have been small regionalist movements: the Vectis National Party and the Isle of Wight Party; but they have attracted little support at elections.[84]

Main towns

- Newport is the centrally located county town, with a population of about 25,000[85] and the island's main shopping area. Located next to the River Medina, Newport Quay was a busy port until the mid-19th century.

- Ryde, the largest town with a population of about 30,000, is in the northeast. It is Victorian with the oldest seaside pier in England and miles of sandy and pebble beaches.

- Cowes hosts the annual Cowes Week and is an international sailing centre.

- East Cowes is famous for Osborne House, Norris Castle and as the home from 1929 to 1964 of Saunders-Roe, the historic aircraft, flying boat, rocket and hovercraft company.

- Sandown is a popular seaside resort. It is home to the Isle of Wight Zoo, the Dinosaur Isle geological museum and one of the island's two 18-hole golf courses.

- Shanklin, just south of Sandown, attracts tourists with its high summer sunshine levels, sandy beaches, Shanklin Chine and the old village.

- Ventnor, built on the steep slopes of St Boniface Down on the south coast of the island, leads down to a picturesque bay that attracts many tourists. Ventnor Haven is a small harbour.

Culture

Language and dialect

The local accent is similar to the traditional dialect of Hampshire, featuring the dropping of some consonants and an emphasis on longer vowels. It is similar to the West Country dialects heard in South West England, but less pronounced.[86][87]

The island has its own local and regional words. Some, such as nipper/nips (a young male person), are still commonly used and are shared with neighbouring areas of the mainland. A few are unique to the island, for example overner and caulkhead (see below). Others are more obscure and now used mainly for comic emphasis, such as mallishag (meaning "caterpillar"), gurt meaning "large", nammit (a mid-morning snack) and gallybagger ("scarecrow", and now the name of a local cheese).[88]

Identity

There remains occasional confusion between the Isle of Wight as a county and its former position within Hampshire.[89] The island was regarded and administered as a part of Hampshire until 1890, when its distinct identity was recognised with the formation of Isle of Wight County Council (see also Politics of the Isle of Wight). However, it remained a part of Hampshire until the local government reforms of 1974 when it became a full ceremonial county with its own Lord Lieutenant.[90]

In January 2009, the first general flag for the county was accepted by the Flag Institute.[91]

Island residents are sometimes referred to as "Vectensians", "Vectians" or, if born on the island, "caulkheads".[92] One theory is that this last comes from the once prevalent local industry of caulking or sealing wooden boats; the term became attached to islanders either because they were so employed, or as a derisory term for perceived unintelligent labourers from elsewhere. The term "overner" is used for island residents originating from the mainland (an abbreviated form of "overlander", which is an archaic term for "outsider" still found in parts of Australia).[93]

Residents refer to the island as "The Island", as did Jane Austen in Mansfield Park, and sometimes to the UK mainland as "North Island".[94]

To promote the island's identity and culture, the High Sheriff Robin Courage founded an Isle of Wight Day; the first was held on Saturday 24 September 2016.

Hauntings

The island is said to be the most haunted in the world, sometimes being referred to as "Ghost Island". Notable claimed hauntings include God's Providence House in Newport (now a tea room), Appuldurcombe House, and the remains of Knighton Gorges.[95]

Sport

Cycling

The island is well known for its cycling, and it was included within Lonely Planet's Best in Travel Guide (2010) top ten cycling locations. The island also hosts events such as the Isle of Wight Randonnée and the Isle of Wight Cycling Festival each year. A popular cycling track is the Sunshine Trail which starts in Newport and ends in Sandown.

Rowing

There are rowing clubs at Newport, Ryde and Shanklin, all members of the Hants and Dorset rowing association.

There is a long tradition of rowing around the island dating back to the 1880s.

In May 1999 a group of local women made history by becoming the first ladies' crew to row around the island, in ten hours and twenty minutes. Rowers from Ryde Rowing Club have rowed around the island several times since 1880. The fours record was set 16 August 1995 at 7 hours 54 minutes.[96]

Two rowers from Southampton ARC (Chris Bennett and Roger Slaymaker) set the two-man record in July 2003 at 8 hours 34 minutes, and in 2005 Gus McKechnie of Coalporters Rowing Club became the first adaptive rower to row around, completing a clockwise row.[97]

The route around the island is about 60 miles (97 km) and usually rowed anticlockwise. Even in good conditions, it includes a number of significant obstacles such as the Needles and the overfalls at St Catherine's Point. The traditional start and finish were at Ryde Rowing Club; however, other starts have been chosen in recent years to give a tidal advantage.

Sailing

Cowes is a centre for sailing, hosting several racing regattas. Cowes Week is the longest-running regular regatta in the world, with over 1,000 yachts and 8,500 competitors taking part in over 50 classes of racing.[98] In 1851 the first America's Cup race was around the island. Other major sailing events hosted in Cowes include the Fastnet race, the Round the Island Race,[99] the Admiral's Cup, and the Commodore's Cup.[100]

Trampolining

There are two main trampoline clubs on the island, in Freshwater and Newport, competing at regional, national and international grades.[101][102]

Marathon

The Isle of Wight Marathon is the United Kingdom's oldest continuously held marathon, having been run every year since 1957.[103] Since 2013 the course has started and finished in Cowes, heading out to the west of the island and passing through Gurnard, Rew Street, Porchfield, Shalfleet, Yarmouth, Afton, Willmingham, Thorley, Wellow, Shalfleet, Porchfield, and Northwood. It is an undulating course with a total climb of 1,043 feet (318 m).

Speedway

The island is home to the Wightlink Warriors speedway team, who compete in the sport's third division, the National League.

Field hockey

Following an amalgamation of local hockey clubs in 2011, the Isle of Wight Hockey Club now runs two men's senior and two ladies' senior teams. These compete at a range of levels in the Hampshire open leagues.[104]

Football

The now-disbanded Ryde Sports F.C., founded in 1888, was one of the eight founder members of the Hampshire League in 1896. There are several non-league clubs such as Newport (IOW) F.C. There is an Isle of Wight Saturday Football League which feeds into the Hampshire League with two divisions and two reserve team leagues, and a rugby union club.[105][106]

Cricket

The Isle of Wight is the 39th official county in English cricket, and the Isle of Wight Cricket Board organises a league of local clubs. Ventnor Cricket Club competes in the Southern Premier League, and has won the Second Division several times. Newclose County Cricket Ground near Newport[107][108] opened officially in 2009 but with its first match held on 6 September 2008.[109] The island has produced some notable cricketers, such as Danny Briggs, who plays county cricket for Sussex.

Island Games

The Isle of Wight competes in the biennial Island Games, which it hosted in 1993 and again in 2011.

Motor scooter

The annual Isle of Wight International Scooter Rally has since 1980 met on the August Bank Holiday. This is now one of the biggest scooter rallies in the world, attracting between four and seven thousand participants.[110]

Golf

There are eight Golf courses on the Isle of Wight.

Music

The island is home to the Isle of Wight Festival and until 2016, Bestival before it was relocated to Lulworth Estate in Dorset. In 1970, the festival was headlined by Jimi Hendrix attracting an audience of 600,000, some six times the local population at the time.[111] It is the home of the bands The Bees, Trixie's Big Red Motorbike and Level 42.[112]

Economy

Socio-economic data

The table below shows the regional gross value (in millions of pounds) added by the Isle of Wight economy, at current prices, compiled by the Office for National Statistics.[113][114]

| Year | Regional gross value added[115] |

Agriculture[116] | Industry[117] | Services[118] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 831 | 28 | 218 | 585 |

| 2000 | 1,369 | 27 | 375 | 800 |

| 2003 | 1,521 | 42 | 288 | 1,161 |

| 2008 | 2,023 | |||

| 2012 | 2,175 |

According to the 2011 census,[119] the island's population of 138,625 lives in 61,085 households, giving an average household size of 2.27 people.

41% of households own their home outright and a further 29% own with a mortgage, so in total 70% of households are owned (compared to 68% for South East England).

Compared to South East England, the island has fewer children (19% aged 0–17 against 22% for the South East) and more elderly (24% aged 65+ against 16%), giving an average age of 44 years for an island resident compared to 40 in South East England.

Industry and agriculture

The largest industry is tourism, but the island also has a strong agricultural heritage, including sheep and dairy farming and arable crops. Traditional agricultural commodities are more difficult to market off the island because of transport costs, but local farmers have succeeded in exploiting some specialist markets, with the higher price of such products absorbing the transport costs. One of the most successful agricultural sectors is now the growing of crops under cover, particularly salad crops including tomatoes and cucumbers. The island has a warmer climate and a longer growing season than much of the United Kingdom. Garlic has been successfully grown in Newchurch for many years, and is even exported to France. This has led to the establishment of an annual Garlic Festival at Newchurch, which is one of the largest events of the local calendar. A favourable climate supports two vineyards, including one of the oldest in the British Isles at Adgestone.[120] Lavender is grown for its oil.[121] The largest agricultural sector has been dairying, but due to low milk prices and strict legislation for UK milk producers, the dairy industry has been in decline: there were nearly 150 producers in the mid-1980s, but now just 24.

Maritime industries, especially the making of sailcloth and boat building, have long been associated with the island, although this has diminished somewhat in recent years. GKN operates what began as the British Hovercraft Corporation, a subsidiary of (and known latterly as) Westland Aircraft, although they have reduced the extent of plant and workforce and sold the main site. Previously it had been the independent company Saunders-Roe, one of the island's most notable historic firms that produced many flying boats and the world's first hovercraft.[122]

Another manufacturing activity is in composite materials, used by boat-builders and the wind turbine manufacturer Vestas, which has a wind turbine blade factory and testing facilities in West Medina Mills and East Cowes.[123]

Bembridge Airfield is the home of Britten-Norman, manufacturers of the Islander and Trislander aircraft. This is shortly to become the site of the European assembly line for Cirrus light aircraft. The Norman Aeroplane Company is a smaller aircraft manufacturing company operating in Sandown. There have been three other firms that built planes on the island.[124]

In 2005, Northern Petroleum began exploratory drilling for oil at its Sandhills-2 borehole at Porchfield, but ceased operations in October that year after failing to find significant reserves.[125]

Breweries

There are three breweries on the island. Goddards Brewery in Ryde opened in 1993.[126] David Yates, who was head brewer of the Island Brewery, started brewing as Yates Brewery at the Inn at St Lawrence in 2000.[127]

Ventnor Brewery, which closed in 2009, was the last incarnation of Burt's Brewery, brewing since the 1840s in Ventnor.[128] Until the 1960s most pubs were owned by Mews Brewery, situated in Newport near the old railway station, but it closed and the pubs were taken over by Strong's, and then by Whitbread. By some accounts Mews beer was apt to be rather cloudy and dark. In the 19th century they pioneered the use of screw top cans for export to British India.[129]

Services

Tourism and heritage

The island's heritage is a major asset that has for many years supported its tourist economy. Holidays focused on natural heritage, including wildlife and geology, are becoming an alternative to the traditional British seaside holiday, which went into decline in the second half of the 20th century due to the increased affordability of foreign holidays.[130] The island is still an important destination for coach tours from other parts of the United Kingdom.

Tourism is still the largest industry, and most island towns and villages offer hotels, hostels and camping sites. In 1999, it hosted 2.7 million visitors, with 1.5 million staying overnight, and 1.2 million day visits; only 150,000 of these were from abroad. Between 1993 and 2000, visits increased at an average rate of 3% per year.[131]

At the turn of the 19th century the island had ten pleasure piers, including two at Ryde and a "chain pier" at Seaview. The Victoria Pier in Cowes succeeded the earlier Royal Pier but was itself removed in 1960. The piers at Ryde, Seaview, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor originally served a coastal steamer service that operated from Southsea on the mainland. The piers at Seaview, Shanklin, Ventnor and Alum Bay were all destroyed by various storms during the 20th century; only the railway pier at Ryde and the piers at Sandown, Totland Bay (currently closed to the public) and Yarmouth survive.

Blackgang Chine is the oldest theme park in Britain, opened in 1843.[132] The skeleton of a dead whale that its founder Alexander Dabell found in 1844 is still on display.[95]

As well as its more traditional attractions, the island is often host to walking[133] or cycling holidays through the attractive scenery. An annual walking festival[134] has attracted considerable interest. The 70 miles (113 km) Isle of Wight Coastal Path follows the coastline as far as possible, deviating onto roads where the route along the coast is impassable.[135]

The tourist board for the island is Visit Isle of Wight, a not for profit company. It is the Destination Management Organisation for the Isle of Wight, a public and private sector partnership led by the private sector, and consists of over 1,200 companies, including the ferry operators, the local bus company, rail operator and tourism providers working together to collectively promote the island. Its income is derived from the Wight BID, a business improvement district levy fund.

A major contributor to the local economy is sailing and marine-related tourism.[136]

Summer Camp at Camp Beaumont is an attraction at the old Bembridge School site.[137]

Transport

The Isle of Wight has 489 miles (787 km) of roadway. It does not have a motorway, although there is a short stretch of dual carriageway towards the north of Newport near the hospital and prison.

A comprehensive bus network operated by Southern Vectis links most settlements, with Newport as its central hub.[138]

Journeys away from the island involve a ferry journey. Car ferry and passenger catamaran services are run by Wightlink and Red Funnel, and a hovercraft passenger service (the only such remaining in the world[139]) by Hovertravel.

The island formerly had its own railway network of over 55 miles (89 km), but only one line remains in regular use. The Island Line is part of the United Kingdom's National Rail network, running a little under 9 miles (14 km) from Shanklin to Ryde Pier Head, where there is a connecting ferry service to Portsmouth Harbour station on the mainland network. The line was opened by the Isle of Wight Railway in 1864, and from 1996 to 2007 was run by the smallest train operating company on the network, Island Line Trains. It is notable for utilising old ex-London Underground rolling stock, due to the small size of its tunnels and unmodernised signalling. Branching off the Island Line at Smallbrook Junction is the heritage Isle of Wight Steam Railway, which runs for 5 1⁄2 miles (8.9 km) to the outskirts of Wootton on the former line to Newport.[140]

There are two airfields for general aviation, Isle of Wight Airport at Sandown and Bembridge Airport.

The island has over 200 miles (322 km) of cycleways, many of which can be enjoyed off-road. The principal trails are:[141]

- The Sunshine Trail, which is a circular route linking Sandown, Shanklin, Godshill, and Wroxall of 12 miles (19 km);

- The Troll Trail between Cowes and Sandown of 13 miles (21 km), 90% off-road;

- The Round the Island Cycle Route of 62 miles (100 km).

Media

The main local newspaper is the Isle of Wight County Press, published most Fridays.

The island hosts a news website, Island Echo,[142] which was launched in May 2012.

The island has a local commercial radio station and a community radio station: commercial station Isle of Wight Radio has broadcast in the medium-wave band since 1990 and on 107.0 MHz (with three smaller transmitters on 102.0 MHz) FM since 1998, as well as streaming on the Internet.[143] Community station Vectis Radio has broadcast online since 2010, and in 2017 started broadcasting on FM 104.6. The station operates from the Riverside Centre in Newport.[144]

The island is also covered by a number of local stations on the mainland, including the BBC station BBC Radio Solent broadcast from Southampton.

The island's not-for-profit community radio station Angel Radio opened in 2007. Angel Radio began broadcasting on 91.5 MHz from studios in Cowes and a transmitter near Newport.[145][146]

Other online news sources for the Isle of Wight include On the Wight.[147]

The island has had community television stations in the past, first TV12 and then Solent TV from 2002 until its closure on 24 May 2007. iWight.tv is a local internet video news channel.

The Isle of Wight is part of the BBC South region and the ITV Meridian region.

Important broadcasting infrastructure includes Chillerton Down transmitting station with a mast that is the tallest structure on the island, and Rowridge transmitting station, which broadcasts the main television signal both locally and for most of Hampshire and parts of Dorset and West Sussex.[148]

Prisons

The Isle of Wight is near the densely populated south of England, yet separated from the mainland. This position led to it hosting three prisons: Albany, Camp Hill and Parkhurst, all located outside Newport near the main road to Cowes. Albany and Parkhurst were among the few Category A prisons in the UK until they were downgraded in the 1990s.[149] The downgrading of Parkhurst was precipitated by a major escape: three prisoners (two murderers and a blackmailer) escaped from the prison on 3 January 1995 for four days, before being recaptured.[150] Parkhurst enjoyed notoriety as one of the toughest jails in the United Kingdom, and housed many notable inmates including the Yorkshire Ripper Peter Sutcliffe, New Zealand drug lord Terry Clark and the Kray twins.

Camp Hill is located adjacent but to the west of Albany and Parkhurst, on the very edge of Parkhurst Forest, having been converted first to a borstal and later to a Category C prison. It was built on the site of an army camp (both Albany and Parkhurst were barracks); there is a small estate of tree-lined roads with the former officers' quarters (now privately owned) to the south and east. Camp Hill closed as a prison in March 2013.

The management of all three prisons was merged into a single administration, under HMP Isle of Wight in April 2009.

Education

There are 69 local education authority-maintained schools on the Isle of Wight, and two independent schools.[151] As a rural community, many of these are small and with fewer pupils than in urban areas. The Isle of Wight College is located on the outskirts of Newport.

From September 2010, there was a transition period from the three-tier system of primary, middle and high schools to the two-tier system that is usual in England.[152] Some schools have now closed, such as Chale C.E. Primary. Others have become "federated", such as Brading C.E. Primary and St Helen's Primary. Christ the King College started as two "middle schools," Trinity Middle School and Archbishop King Catholic Middle School, but has now been converted into a dual-faith secondary school and sixth form.

Since September 2011 five new secondary schools, with an age range of 11 to 18 years, replaced the island's high schools (as a part of the previous three-tier system).

Notable residents

Notable residents have included:

17th century and earlier

- King Arwald, last pagan king in England

- King Charles I of England, who was imprisoned at Carisbrooke Castle

- Viking Earl Tostig Godwinson

- Actor, highwayman and conspirator Cardell "Scum" Goodman

- Soldier and regicide of Charles I Thomas Harrison, imprisoned at Carisbrooke with John Rogers & Christopher Feake

- Soldier Peter de Heyno

- Philosopher and polymath Robert Hooke

- Murderer Michal Morey

18th century

- Marine painter Thomas Buttersworth

- Explorer Anthony Henday

- Radical journalist John Wilkes

19th century

- Queen Victoria and Prince Albert (monarch and consort), who built and lived at Osborne House

- Photographer Julia Margaret Cameron, who lived at Dimbola Lodge

- Irish Republican Thomas Clarke

- Naval captain Jeremiah Coghlan CBG, who retired to Ryde

- Writer Charles Dickens

- Poet John Keats

- Inventor and radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi

- Poet and hymnwriter Albert Midlane

- Geologist and engineer John Milne

- Regency architect John Nash

- Novelist Miss Harriet Parr

- Early Hong Kong Government administrator William Pedder

- New Zealand PM Henry Sewell

- Poet Algernon Charles Swinburne

- Poet Alfred Tennyson

- Philosopher Karl Marx, who stayed at 1, St. Boniface Gardens, Ventnor

20th century onwards

- Scriptwriter Raymond Allen

- Indie rock group The Bees

- Concert organist E. Power Biggs

- Darts player Keegan Brown

- Singer-songwriter Sarah Close

- Inventor of the hovercraft Sir Christopher Cockerell

- Presenter and actor Ray Cokes

- Actress Bella Emberg

- Yachtsman Uffa Fox

- Actor Marius Goring

- Survival expert and Chief Scout Bear Grylls

- Actress Sheila Hancock

- Folk-rock musician Robyn Hitchcock

- Actor Geoffrey Hughes

- Conspiracy theorist David Icke

- Actor Jeremy Irons

- Comedian Phill Jupitus

- Actor Laura Michelle Kelly

- Composer Albert Ketèlbey

- Iranian poet Mimi Khalvati

- Musician Mark King

- Radio presenter Allan Lake

- Musician Jack Green

- Yachtswoman Ellen MacArthur

- BBC 'Tonight' presenter Cliff Michelmore

- Film director Anthony Minghella

- Actor David Niven

- Cyclist Kieran Page

- Heptathlete Kelly Sotherton

- Gardener and presenter Alan Titchmarsh

- Novelist Edward Upward

- Actor Melvyn Hayes

Places of interest

| Key | |

| Abbey/Priory/Cathedral | |

| Accessible open space | |

| Amusement/Theme Park | |

| Castle | |

| Country Park | |

| English Heritage | |

| Forestry Commission | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

| Mosques | |

| Museum (free/not free) | |

| National Trust | |

| Theatre | |

| Zoo | |

- Alum Bay

- Appuldurcombe House

- Amazon World Zoo

- Bembridge Lifeboat Station

- Blackgang Chine

- Brading Roman Villa

.png)

- Carisbrooke Castle

- Classic Boat Museum, East Cowes

.png)

- Compton Bay

- Dimbola Lodge

.png)

- Dinosaur Isle

.png)

- Fort Victoria

- Godshill village and model village

- Isle of Wight Bus & Coach Museum

.png)

- Isle of Wight Steam Railway

- Isle of Wight Zoo, Yaverland

- Medina Theatre

- The Needles

- Newport Roman Villa.

- Osborne House

- Quarr Abbey

- Robin Hill

- Botanic Gardens, Ventnor

- Yarmouth Castle

Overseas names

The Isle of Wight has given names to many parts of former colonies, most notably Isle of Wight County in Virginia founded by settlers from the island in the 17th century. Its county seat is a town named Isle of Wight.

Other notable examples include:

- Isle of Wight - an island off Maryland, United States

- Dunnose Head, West Falkland

- Ventnor, Cowes on Philip Island, Victoria, Australia

- Carisbrook, Victoria, Australia

- Carisbrook, a former stadium in Dunedin, New Zealand

- Ryde, New South Wales, Australia

- Shanklin, Sandown, New Hampshire, United States

- Ventnor City, New Jersey, United States

- Gardiners Island, New York, United States shown as "Isle of Wight" on some of the older maps.[153]

Media references

Film

- The film Something to Hide (1972; US title Shattered), starring Peter Finch, was filmed near Cowes, including a scene on the Red Funnel ferry;

- The British film That'll Be the Day (1973), starring David Essex and Ringo Starr, included scenes shot in Ryde (notably Cross Street), Sandown (school), Shanklin (beach) and Wootton Bridge (fairground);

- Mrs. Brown (1997), with Dame Judi Dench and Billy Connolly, was filmed at Osborne and Chale;

- The film Fragile (2005), starring Calista Flockhart, is based on the Isle of Wight.

- Victoria and Abdul (2017) starring Dame Judi Dench and Ali Fazal began shooting principal photography at Osborne House in September 2016.

Games

- John Worsley's Commodore 64 game Spirit of the Stones was set on the Isle of Wight.[154]

Literature

The Isle of Wight was:[155]

- the setting of Julian Barnes's novel England, England;

- called The Island in some editions of Thomas Hardy's novels in his fictional Wessex;

- selected for the development of a new base by the supercomputer "Colossus", in D. F. Jones' novel Colossus (1966);

- the setting for D.H. Lawrence's book The Trespasser, filmed for TV on location in 1981;

- the setting of Graham Masterton's book Prey;

- mentioned in J.K. Rowling's first Harry Potter book, which refers to Uncle Vernon's sister Marge on holiday on the island, who got sick after eating a whelk;

- a major element in Daniel O'Malley's series The Rook (2012) & its sequel Stiletto (2016). The antagonists try to invade in the 1600s, the effects of which continue to colour perceptions of the Crown's secret supernatural agency, the "Checquy Group";

- the refuge of the British monarchy & government in S.M. Stirling's alternative history novel The Protector's War (2005), in which high energy technology ceased to function. After an ensuing holocaust, the island was the base for re-population of Europe, whose populations had mostly perished;

- one of the destinations to which the British government evacuates in Frank Tayell's post-apocalyptic novel Surviving the Evacuation Book One: London (2013), guided by the mistaken impression that it would be defensible against the zombie hordes;[156]

- featured in John Wyndham's novel The Day of the Triffids and Simon Clark's sequel The Night of the Triffids.

Music

- The Beatles' song "When I'm Sixty-Four" (1967), credited to Lennon-McCartney and sung by Paul McCartney, refers to renting a cottage on the island;[157]

- Bob Dylan recorded "Like a Rolling Stone" (1965), "Minstrel Boy", "Quinn the Eskimo (The Mighty Quinn)" (1967), and "She Belongs to Me" (1965) for the album Self Portrait (1970) live on the island;

- "Wight Is Wight" (1969), a song by French artist Michel Delpech, also spawned an Italian cover by Dik Dik, titled "L'isola di Wight"(IT) (1970).

Radio

- There was a running joke in radio sitcom The Navy Lark involving Sub-Lieutenant Phillips's inability to navigate and subsequently tail the Isle of Wight ferry.[158]

Television

- ITV's dramatisation of Dennis Potter's work Blade on the Feather (19 October 1980) was filmed on the island.[159]

- The 1984 TV miniseries, Annika, was partly filmed in Ryde.

- A 2002 Top Gear feature showed an Aston Martin being driven around Cowes, East Cowes, and along the Military Road and seawall at Freshwater Bay.[160]

- The setting for Free Rein was based on the Isle of Wight.[161]

See also

- List of civil parishes on the Isle of Wight

- List of places on the Isle of Wight

- List of current places of worship on the Isle of Wight

- List of High Sheriffs of the Isle of Wight

- List of Lord Lieutenants of the Isle of Wight

- List of Governors of the Isle of Wight

- List of hills of the Isle of Wight

- Isle of Wight gasification facility

- Isle of Wight NHS Trust

- Isle of Wight Rifles

- Yaverland Battery

Notes

- As well as the former Princess Beatrice during World War II, most otherwise notable was Lord Mountbatten in 1969–1974, after which he became Lord Lieutenant until his assassination in 1979.

References

- "Chris Hadfield on Twitter".

- "Queen appoints new Lord-Lieutenant of the Isle of Wight". GOV.UK. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- "No. 62943". The London Gazette. 13 March 2020. p. 5161.

- "2011 Census, Key Statistics for Local Authorities in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. 2011. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Isle of Wight Festival history". Redfunnel.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Isabella de Fortibus, "Queen of the Wight" - English Heritage".

- "Portsmouth agrees to launch Solent Combined Authority bid". BBC News. BBC. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Solent Combined Authority bid 'almost certainly dead'". BBC. 26 January 2017. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Wenban-Smith, Francis. "The Pleistocene sequence at Priory Bay, Isle of Wight (SZ 635 900)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/8000-year-old-boat-building-platform-found-coast-britain-180972989/

- Adams, William Henry Davenport (1877). Nelsons' hand-book to the Isle of Wight. Oxford University. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Hawkes, C. F. C. (July 1984). "Ictis disentangled, and the British tin trade". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 3 (2): 211–233. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.1984.tb00327.x. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- Snodgrass, A. M. (1966). Arms and Armour of the Greeks. Thames & Hudson, London.

- Snodgrass, A. M. (1971). The Dark Age of Greece. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh.

- Williams, Jonathan; Hill, J.D., Portable Antiquities Scheme, Record ID: IOW-38B400.

- The Isle of Wight Ingot Hoard The Art Fund

- Leins, Ian; Joy, Jody; Basford, Frank , Portable Antiquities Scheme, Record ID: IOW-EAAFE2.

- Leslie, et al. 2015, Stephen (2015). "The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population". Nature. 519 (March 2015): 309–314. doi:10.1038/nature14230. PMC 4632200. PMID 25788095.

- Wellington, Imogen (February 2001). "Iron Age Coinage on the Isle of Wight". Oxford Journal of Archaeology. 20 (1): 39–57. doi:10.1111/1468-0092.00122.

- Crawford, Osbert Guy Stanhope (1912). "The distribution of early bronze age settlements in Britain" (PDF). Geographical Journal. 1912: 184–197.

- Adams, William Henry Davenport (1877). Nelson's Hand-book to the Isle of Wight. Oxford.

- "Romano-British Occupation". Vectis. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- The Journal of the British Archaeological Association (PDF). December 1866. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- McMahon, Rob. "Why Populations". McMahon. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Bede, the Venerable (790). Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Smith, Oliver; et al. (27 February 2015). "Sedimentary DNA from a submerged site reveals wheat in the British Isles 8000 years ago" (PDF). Science. 347 (6225): 998–1001. doi:10.1126/science.1261278. PMID 25722413.

- Cunliffe, Barry (2008). A Companion to Roman Britain: Britain and the continent: networks of interaction. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–11. ISBN 9780470998854.

- Balter, Michael (26 February 2015). "DNA recovered from underwater British site may rewrite history of farming in Europe". Science. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "The Isle of Wight Ingot Hoard". The Art Fund.

- "Saxon Graves at Shalfleet". Isle of Wight History Centre. August 2005. Archived from the original on 1 November 2006.

- Williams, Peter N. "England, A Narrative History". Britannia.com. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Harding, Samuel B. "The English Accept Christianity". The Story of England.

- The Anglo Saxon Chronicle. 1116.

- "Anglo-Saxon Isle of Wight: 900 - 1066 AD". 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Victoria County History". British History Online, University of London & History of Parliament Trust. 1912. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Victoria County History". British History Online, University of London & History of Parliament Trust. 1912. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- English Heritage. "Isabella de Fortibus, "Queen of the Wight"". English Heritage Story of England. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Fernández Duro, Cesáreo (1995). La Marina de Castilla. Madrid. ISBN 978-84-86228-04-0.

- Chisholm, Hugh (1911). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 627.

- English Heritage. "English Heritage Story of England". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Longmate, Norman (2001). Island Fortress: The Defence of Great Britain, 1603–1945. London. pp. 186–188.

- "Fort Nelson History". Royal Armouries. Archived from the original on 20 November 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- "Isle of Wight history and heritage". visitisleofwight.co.uk. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Visiting the Isle of Wight: Queen Victoria Trail

- Why does the Queen use a “bathing machine” to go swimming in ITV’s Victoria?

- The Queen's Bathing Machine

- Victoria's plunge: Queen's beach to open to public

- "140 YEARS SINCE FIRST TELEPHONE CALL TO QUEEN VICTORIA ON THE ISLE OF WIGHT". Island Echo. 14 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

He made the UK’s first publicly-witnessed long distance calls, calling Cowes, Southampton and London from Osborne House. Queen Victoria liked the telephone so much she wanted to buy it.

- "Alexander Graham Bell demonstrates the newly invented telephone". The Telegraph. 13 January 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

one of the Queen’s staff wrote to Professor Bell to inform him "how much gratified and surprised the Queen was at the exhibition of the Telephone"

- "pdf, Letter from Alexander Graham Bell to Sir Thomas Biddulph, February 1, 1878". Library of Congress. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

The instruments at present in Osborne are merely those supplied for ordinary commercial purposes, and it will afford me much pleasure to be permitted to offer to the Queen a set of Telephones to be made expressly for her Majesty's use.

- Ross, Stewart (2001). Alexander Graham Bell. (Scientists who Made History). New York: Raintree Steck-Vaughn. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-7398-4415-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Eric (2005). How internet radio can change the world: an activist's handbook. New York: iUniversr, Inc. ISBN 9780595349654. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- "Connected Earth". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- Marconi Statue

- "What happened to the National Wireless Museum?". Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Julia Skinner (2012). Isle of Wight: A Miscellany. www.francisfrith.com. ISBN 978-1-84589-683-6.

- "PLUTO pumping station, Sandown, Isle of Wight". D-Day Museum and Overlord Embroidery. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Welcome to Britain's secret Cape Canaveral (... on the Isle of Wight)". London Evening Standard. 31 March 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Movies". Movies.msn.com. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Isle of Wight Festival History 1968 to Today". isleofwightguru.com. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Eilert Ekwall, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names, 4th ed. (Oxford University Press, 1960) p. 518

- A. L. F. Rivet, Colin Smith, The Place-Names of Roman Britain (Batsford, 1979) pp. 487-489

- "VECTIS - Roman Republic". romanrepublic.org.

- "Isle of Wight joins Unesco's network of biosphere sites". www.bbc.co.uk. 19 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Staff writer(s); no by-line (1987–2012). "St Boniface Down, England". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

- Hopson P. (2011). "The geological history of the Isle of Wight: an overview of the 'diamond in Britain's geological crown'" (PDF). Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 122 (5): 745–763. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2011.09.007.

- "Fossil and Dinosaur Hunting". redfunnel.co.uk. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- Booth K.A. & Brayson J. (2011). "Geology, landscape and human interactions: examples from the Isle of Wight" (PDF). Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 122 (5): 938–948. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2011.01.004.

- "Isle of Wight Climate Statistics". Archived from the original on 21 April 2008.

- weatheronline.co.uk. "Frost Days data 2000-2008 St Catherine's Point". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Hardiness Zone Map for Europe". GardenWeb. 1999.

- "Operation Squirrel". Iwight.com. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Deer could damage Island warning". Iwcp.co.uk. 17 August 2010. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Natural History of Red Deer". Wildlife Online. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- http://www.bds.org.uk/index.php/documents/deer-species/12-muntjac-deer-poster/file

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Glanville Fritillary". UK Butterflies. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Pyramidal orchid". Plantlife. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- "Turner Will Fight On For 'Unique' Island Status". Isle of Wight Chronicle. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013.

- "Isle of Wight Set To Have Two MPs in 2015". Isle of Wight Chronicle. 15 February 2011. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011.

- "Isle Of Wight MP Andrew Turner survives no confidence vote". BBC. 24 January 2015.

- "Isle of Wight council results". BBC News. 29 April 2013.

- "Hampshire & IoW election results: Conservatives take control". BBC News. 5 May 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- Adam Grydehøj and Philip Hayward (2011). Autonomy Initiatives and Quintessential Englishness on the Isle of Wight (PDF). Island Studies Journal. p. 185.

- "Newport Parish Council, Isle of Wight, Official Website". Newport Parish Council - Isle of Wight. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- University of Leeds (1959). "Survey of English Dialects: Whitwell, Isle of Wight". British Library. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- W Long (1886). A dictionary of the Isle of Wight dialect (PDF). Reeves & Turner, London.

- Lavers, Jack (1988). The Dictionary of the Isle of Wight Dialect. Dovecote Press. ISBN 978-0-946159-63-5.

- "Oiled birds may be linked to Ice Prince sinking". The Daily Telegraph. UK. 16 January 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- UK Government (1972). "Local Government Act 1972". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Flag institute". Flag institute. 6 July 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Why are natives of the Isle of Wight known as 'caulkheads'? - Notes and Queries". www.theguardian.com. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- overlander Archived 31 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Celebrate all things Island on Isle of Wight Day". www.redfunnel.co.uk. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- "Default What happened to the National Wireless Museum?". Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Ryde Rowing Club (1999). "Record round the Isle of Wight row". University of Oxford. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- redfunnel.co.uk. "About Gus McKechnie - Fundraising Legend!". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Skandia Cowes Week 2008 – Welcome". Skandiacowesweek.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "JPMorgan Asset Management Round the Island Race". Roundtheisland.org.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Rolex Commodores' Cup – Home". Rorc.org. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Club directory". Isle of Wight Council. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Wight Flyers Trampoline & Gymnastics Club". Wight Flyers. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Isle Of Wight Marathon Race". Rydeharriers.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 February 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Isle of Wight Hockey Club". Isle of Wight Hockey Club. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "The Isle has produced several high profile players including Kevin "The Hitman" Broderick, now playing for a local Sunday side. Isle Of Wight Rugby Football Club". Iwrfc.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Isle of Wight Sport". Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- "Isle of Wight County Cricket Ground". Isle of Wight Cricket Board. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Newclose: Cricket Scoreboard Arrives | Isle of Wight News". Ventnor Blog. 10 July 2008. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Newclose County Cricket Ground Open Days". Isle of Wight Cricket Board. Retrieved 21 November 2008.

- "Scooter rally takes place on Isle of Wight". bbc.co.uk. 27 August 2013. Archived from the original on 29 August 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- "Concerts with Record Attendance". Noiseaddicts.com. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- "Trixie's Big Red Motorbike – Discover music, concerts, stats, & pictures at". Last.fm. 11 February 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- published (pp.240–253) Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Annual estimates of NUTS3 regional Gross Value Added (GVA)". Office for National Statistics. 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Components may not sum to totals due to rounding

- includes hunting and forestry

- includes energy and construction

- includes financial intermediation services indirectly measured

- "Key census statistics, Isle of Wight Authority area". 2011. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- "Wine for Sale – Vineyard Tours, Isle of Wight". English Wine. Archived from the original on 18 July 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Isle of Wight lavender farm, lavender products, lavender plants, teas". Lavender.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Antony Barton. "Saunders-Roe/Westland Aircraft/British Hovercraft Corporation". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Isle of Wight wind turbine firm Vestas creates 200 jobs". BBC News. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "A list of aircraft and airplane manufacturers as well as airfields on the Isle of Wight". Daveg4otu.tripod.com. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Ian West (2016). "Petroleum Geology - South of England: The Portland - Isle of Wight Offshore Basin". Southampton University. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "about us". Goddards-brewery.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 March 2001. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Yates' Brewery". Yates-brewery.co.uk. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- Ventnor Brewery:: Since 1840 Archived 5 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Isle of Wight Nostalgia". Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "A POTTED HISTORY OF ISLE OF WIGHT HOLIDAYS". redfunnel.co.uk. 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "A website with Isle of Wight statistics for investors". Investwight.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "The World's Oldest Amusement Parks". Huffington Post. 21 September 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Isle of Wight walking holidays". Wight Walks. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- "Welcome to the official website of the Isle of Wight Walking Festival 2013". Isleofwightwalkingfestival.co.uk. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Isle of Wight Coastal Path". Long Distance Walkers Association. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Draft Tourism Development Plan" (PDF). Isle of Wight Council. 2005. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Coastal Adventure: Isle of Wight". Kingswood Camps. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Southern Vectis bus route map". Southern Vectis. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Summer Southsea-Sandown hovercraft route plans dropped". BBC News. 4 July 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- "Isle of Wight Steam Railway". Isle of Wight Steam Railway. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Isle of Wight Cycle Hire & Cycling Guide - Isle Cycle - Cowes & Sandown".

- "Island Echo". island Echo. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "Isle of Wight Radio 107.0 Newport". internetradiouk.com. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Vectis Radio". www.vectisradio.com.

- ""History of Our Station" and "Gallery"". Angel Radio Isle of Wight Website. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- "The Record Library". Angel Radio Isle of Wight Website. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- "On The Wight". On The Wight. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- "The Big Tower: Chillerton Down". thebigtower.com. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- "Isle of Wight Prison information". UK Justice Department. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- James Cusick (10 January 1995). "The Parkhirst (sic) Breakout: Fugitives were trapped by the sea". The Independent Newspaper. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Schools and Learning". Isle of Wight Council. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- David Newbie (25 September 2009). "It's all change in schools' shake up". Isle of Wight County Press. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Palaces for the People - Panoramic Views".

- "The Lost Talismans of Spirit of the Stones". Archived from the original on 7 February 2005.

- "The Isle of Wight's Literary Connections". h2g2.com. 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- Tayell, Frank (2013). Surviving the Evacuation Book One London.

- "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club band". Lib.ru. 16 May 1996. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- The Navy Lark Volume 24: You're A Rotten!. amazon.co.uk. ASIN 1408468735.

- "Blade on the Feather (1980)". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- "Top Gear on the Isle of Wight, starring Red Funnel and the Military Road". Isle of Wight Guru. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- "Isle of Wight". yoppul.co.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Hansard, Wednesday 14 November 2001 column 850

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isle of Wight. |

| Look up Isle of Wight in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Isle of Wight. |

| External video | |

|---|---|

- Visit Isle of Wight Official Website

- Isle of Wight Council website

- Isleofwight.com

- Isle of Wight at Curlie

Photos

- Images of the Isle of Wight at the English Heritage Archive