Midland Main Line

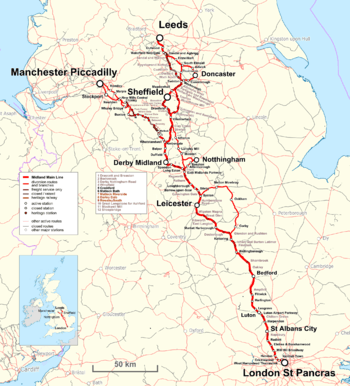

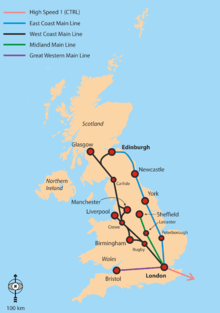

The Midland Main Line is a major railway line in England from London to Nottingham and Sheffield in the north of England. The line is under the Network Rail description of Route 19;[2] it comprises the lines from London's St Pancras station via Leicester, Derby/Nottingham and Chesterfield in the East Midlands.

Midland Main Line | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Midland Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Express passenger services on the line are operated by East Midlands Railway. The section between St Pancras and Bedford is electrified and forms the northern half of Thameslink, with a semi-fast service to Brighton and other suburban services.

A northern part of the route, between Derby and Chesterfield, also forms part of the Cross Country Route operated by CrossCountry. Tracks from Nottingham to Leeds via Barnsley and Sheffield are shared with Northern. East Midlands Railway also operates regional and local services using parts of the line.

History

Midland Counties early developments

The Midland Main Line was built in stages between the 1830s and the 1870s. The earliest section was opened by the Midland Counties Railway between Nottingham and Derby on 4 June 1839.[3] On 5 May 1840 the section of the route from Trent Junction to Leicester was opened.[4]

The line at Derby was joined on 1 July 1840 by the North Midland Railway to Leeds Hunslet Lane via Chesterfield, Rotherham Masborough[n 1], Swinton and Normanton.

On 10 May 1844 the North Midland Railway, the Midland Counties Railway and the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway merged to form the Midland Railway.

Midland Main Line southern extensions

Without its own route to London, the Midland Railway relied upon a junction at Rugby with the London and Birmingham Railway line for access to the capital at London Euston. By the 1850s the junction at Rugby had become severely congested. The Midland Railway employed Thomas Brassey to construct a new route from Leicester to Hitchin via Kettering, Wellingborough and Bedford.[5] giving access to London via the Great Northern Railway from Hitchin. The Crimean War resulted in a shortage of labour and finance, and only £900,000 (equivalent to £86,490,000 in 2019)[6] was available for the construction, approximately £15,000 for each mile.[7] To reduce construction costs the railway followed natural contours, resulting in many curves and gradients. Seven bridges and one tunnel were required, with 60 ft cuttings at Desborough and Sharnbrook. There are also major summits at Kibworth, Desbrough and at Sharnbrook where a 1 in 119 gradient from the south over 3 miles takes the line to 340 feet (100 m) above sea level. This route opened for coal traffic on 15 April 1857, goods on 4 May and passengers on 8 May[8] and the section between Leicester and Bedford is still part of the Midland Main Line.

While this took some of the pressure off the route through Rugby, the GNR insisted that passengers for London alight at Hitchin, buying tickets in the short time available, to catch a GNR train to finish their journey. James Allport arranged a seven-year deal with the GN to run into Kings Cross for a guaranteed £20,000 a year (equivalent to £1,920,000 in 2019).[6] Through services to London were introduced in February 1858.[9]

This line met with similar capacity problems at Hitchin as the former route via Rugby, so a new line was constructed from Bedford via Luton to St Pancras[10] which opened on 1 October 1868.[7] The construction of the London extension cost £9 million[11] (equivalent to £816 million in 2019).

As traffic built up, the Midland opened a new deviation just north of Market Harborough railway station on 26 June 1885 to remove the flat crossing of the Rugby and Stamford Railway.[12]

Northernmost sections

Plans by the Midland Railway to build a direct line from Derby to Manchester were thwarted in 1863 by the builders of the Buxton line who sought to monopolise on the West Coast Main Line.

In 1870 the Midland Railway opened a new route from Chesterfield to Rotherham which went through Sheffield via the Bradway Tunnel.

The mid-1870s saw the Midland line extended northwards through the Yorkshire Dales and Eden Valley on what is now called the Settle–Carlisle Railway.

Before the line closures of the Beeching era, the lines to Buxton and via Millers Dale during most years presented an alternate (and competing) main line from London to Manchester, carrying named expresses such as The Palatine and the "Blue Pullman" diesel powered Manchester - London service ( the " Midland Pullman"). Express trains to Leeds and Scotland such as the Thames–Clyde Express mainly used the Midland's corollary Erewash Valley line, returned to it then used the Settle–Carlisle line. Expresses to Edinburgh Waverley, such as The Waverley travelled through Corby and Nottingham.

Under British Railways and privatisation

Most Leicester-Nottingham local passenger trains were taken over by diesel units from 14 April 1958, taking about 51 minutes between the two cities.[13]

When the Great Central Main Line closed in 1966, the Midland became the only direct main-line rail link between London and the East Midlands and parts of South Yorkshire.

The Beeching cuts and electrification of the West Coast Main Line brought an end to the marginally longer London–Manchester service via Sheffield.

In 1977 the Parliamentary Select Committee on Nationalised Industries recommended considering electrification of more of Britain's rail network, and by 1979 BR presented a range of options that included electrifying the Midland Main Line from London to Yorkshire by 2000.[14] By 1983 the line had been electrified from Moorgate to Bedford, but proposals to continue electrification to Nottingham and Sheffield were not implemented.

The introduction of the High Speed Train (HST) in May 1983, following the Leicester area resignalling, brought about an increase of the ruling line speed on the fast lines from 90 miles per hour (140 km/h) to 110 miles per hour (180 km/h).

Between 2001 and 2003 the line between Derby and Sheffield was upgraded from 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) to 110 miles per hour (180 km/h) as part of Operation Princess, the Network Rail funded CrossCountry route upgrade.

In January 2009 a new station, East Midlands Parkway, was opened between Loughborough and Trent Junction, to act as a park-and-ride station for suburban travellers from East Midlands cities and to serve nearby East Midlands Airport.[15]

Most recently 125 miles per hour (201 km/h) running has been introduced on extended stretches. Improved signalling, increased number of tracks and the revival of proposals to extend electrification from Bedford to Sheffield are underway. Much of this £70 million upgrade, including some line-speed increases, came online on 9 December 2013[16] (see below).

Network Rail route strategy for freight 2007

Network Rail published a Route Utilisation Strategy for freight in 2007;[17] over the coming years a cross-country freight route will be developed enhancing the Birmingham to Peterborough Line, increasing capacity through Leicester, and remodelling Syston and Wigston junctions.

Network Rail 2010 route plan

Traffic levels on the Midland Main Line are rising faster than the national average, with continued increases predicted. In 2006 the Strategic Rail Authority produced a Route Utilisation Strategy for the Midland Main Line to propose ways of meeting this demand;[18] Network Rail started a new study in February 2008 and this was published in February 2010.[19] [20][21][22] After electrification, the North Northamptonshire towns (Wellingborough, Kettering and Corby) are planned to have an additional 'Outer Suburban service' into London St Pancras, similar to the West Midlands Trains' Crewe – London Euston services to cater for the growing commuter market. North Northamptonshire is a major growth area, with over 7,400 new homes planned to be built in Wellingborough[23] and 5,500 new homes planned for Kettering.[24][25]

Highlights include:[26]

- Work related to line speed increases, removing foot crossings and replacing with footbridges

- Various capacity enhancements for freight

- Re-signalling of the entire route, expected to be complete by 2016 when all signalling will be controlled by the East Midlands signalling centre in Derby.[27]

- Rebuilding Bedford and Leicester.[28]

- Accessibility enhancements at Elstree & Borehamwood, Harpenden, Loughborough, Long Eaton, Luton and Wellingborough by 2015.[29]

- Upgraded approach signalling (flashing yellow aspects) added at key junctions – Radlett, Harpenden and Leagrave allowing trains to traverse them at higher speeds.

- Lengthening of platforms at Wellingborough, Kettering, Market Harborough, Loughborough, Long Eaton and Beeston stations as well as work related to the Thameslink Programme (see below).

- Realignment of the track and construction of new platforms to increase the permissible speed through Market Harborough station from 60 mph to 85 mph saving between 30 – 60 seconds.

- Electrification (below)

- Re-doubling the Kettering to Oakham Line between Kettering North Junction and Corby as well as re-signalling to Syston Junction via Oakham. This will allow a half hourly London to Corby passenger service (from an infrastructure perspective) from December 2017, and will create additional paths for rail freight.[30][31]

Electrification

On 16 July 2012, the Department for Transport announced plans to reconfigure the existing electrified section and to electrify most of the line by 2020 at an expected cost of £800 million.[32] In January 2013 Network Rail expected the electrification to cost £500 million and be undertaken in stages during Control Period 5 (April 2014 – March 2019),[33] with Bedford to Corby section electrified by 2017, Kettering to Derby and Nottingham by 2019 and Derby to Sheffield by 2020.[34]

In the Route Utilisation Strategy, Network Rail recommended the Class 801 in 10 car formations for the InterCity services,[35] two 775 metres (848 yd) freight loops south of Bedford and between Kettering and Leicester for longer and heavier freight services, additional infrastructure to accommodate additional freight and passenger train paths and also recommended an additional stop at Kettering for the semi-fast London-Sheffield service.

The electrification plan was part of the wider Electric Spine project to create an electrified route from the Port of Southampton to Sheffield and possibly Doncaster. The project planned to electrify the Varsity Line (Bedford – Oxford), the Cherwell Valley/Great Western Main Lines (Oxford/Aynho Junction – Reading) and the Reading to Basingstoke Line. The South Western Main Line between Basingstoke and Southampton would have been converted to overhead AC electrification from third rail DC power.[30]

The plans were put on hold in June 2015 by the Transport Secretary, Patrick McLoughlin.[36] In September 2015, the Department for Transport announced revised completion dates of 2019 for Corby and Kettering and 2023 for the line further north to Leicester, Nottingham and Sheffield.[37][38]

On 20 July 2017, it was announced that the Kettering-Leicester-Nottingham/Derby-Sheffield electrification project had been cancelled and that bi-mode trains would be used on the route.[39]

The section of line between Clay Cross and Sheffield is planned to be electrified for HS2 by 2033 to enable classic-compatible services to reach Sheffield along the "M18/Eastern Route", this will leave an approximate 70 mile non-electrified "gap" between Kettering North Junction and Clay Cross.[40]

On 6 November 2017 it was announced that Carillion Powerlines had been awarded the contract by Network Rail for the electrification from Bedford to Kettering and Corby.[41] The contract is valued at £260m. The installation of overhead catenary is due to be completed by December 2019. A separate contract was awarded at the same time to the same company for £62m track upgrades on the same route. The first overhead line mast was installed in November 2017.[42]

On 26 February 2019 Andrew Jones, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Transport, announced that electrification would be extended northwards from Kettering to Market Harborough, enabling the connection of the railway to a new power supply point at Braybrooke.[43]

Thameslink Programme

The Thameslink Programme has lengthened the platforms at most stations south of Bedford to 12-car capability. St Pancras, Cricklewood, Hendon and Luton Airport Parkway were already long enough, but bridges at Kentish Town mean it cannot expand beyond the current 8-car platform length. West Hampstead Thameslink has a new footbridge and a new station building. In September 2014 the current Thameslink Great Northern franchise was awarded and trains on this route are currently operated by Thameslink. In 2018 the Thameslink network will expand when some Southern services are merged into it.

Station improvements

In 2013/14 Nottingham station was refurbished and the platforms restructured.

As part of Wellingborough's Stanton Cross development, Wellingborough station is to be expanded.[44]

Ilkeston between Nottingham and Langley Mill was opened on 2 April 2017.[45]

Two new stations are planned:

- Brent Cross Thameslink between Cricklewood and Hendon as part of the Brent Cross Cricklewood development in North London.[46]

- Wixams between Flitwick and Bedford as part of the new town just outside Bedford. Expected to be built by 2015[47] but now scheduled for 2019.[48]

Some new stations have been proposed:

- Clay Cross between Chesterfield and Ambergate/Alferton.[49]

- Irchester (Rushden Parkway) between Wellingborough and Bedford.[50]

- Ampthill between Bedford and Flitwick.[51]

Route definition

The term Midland Main Line has been used from the late 1840s to describe any route of the Midland Railway on which express trains were operated.

It is first recorded in print in 1848 in Bradshaw's railway almanack of that year.[52] In 1849 it begins to be mentioned regularly in newspapers such as the Derby Mercury.[53]

In 1867 the Birmingham Journal uses the term to describe the new railway running into St Pancras railway station.[54]

In 1868 the term was used to describe the Midland Railway main route from North to South through Sheffield[55] and also on routes to Manchester, Leeds and Carlisle.

Under British Rail the term was used to define the route between St Pancras and Sheffield, but in more recent times, Network Rail has restricted it in its description of Route 19[2] to the lines between St. Pancras and Chesterfield.

Accidents

- 26 September 1860 Bull bridge accident; bridge collapse

- 2 September 1861 Kentish Town rail accident; collision

- 2 September 1898 Wellingborough rail accident; derailment due to post trolley on track

- 24 December 1910 Hawes Junction rail crash; signalman forgot about train

- 2 September 1913 Ais Gill rail accident; collision

- 3 December 1923 Nunnery Colliery

- 13 December 1926 Orgreave Paddy Mail accident

- 1 February 2008 Barrow upon Soar rail accident

Operators

East Midlands Railway

The principal operator is East Midlands Railway, which operates five InterCity trains every hour from London St Pancras with two trains per hour to both Nottingham and Sheffield and one train per hour to Corby. EMR use Class 222 Meridian trains in various carriage formations for most of its InterCity services. Older 8 coach High Speed Trains are used for its Nottingham fast service as well morning/evening Leeds services.

Thameslink

Thameslink provides frequent, 24-hour[56] commuter services south of Bedford as part of its Thameslink route to London Bridge, Gatwick Airport, Brighton and Sutton, using 8-car and 12-car electric Class 700 trains.[57]

Other operators

CrossCountry runs half-hourly services between Derby and Sheffield on its route between the South West and North East, and hourly services from Nottingham to Birmingham and Cardiff. Northern runs an hourly service to Leeds from Nottingham via Alfreton and Barnsley.

Other operators include TransPennine Express in the Sheffield area.

Route description

The cities, towns and villages currently served by the MML are listed below. Stations in bold have a high usage. This table includes the historical extensions to Manchester (where it linked to the West Coast Main Line) and Carlisle (via Leeds where it meets with the 'modern' East Coast Main Line).

Network Rail groups all lines in the East Midlands and the route north as far as Chesterfield and south to London as route 19. The actual line extends beyond this into routes 10 and 11.

London to Nottingham and Sheffield (Network Rail Route 19)

| Station | Village/town/city and county | Ordnance Survey grid reference |

Year opened | Step free access | No. of platforms | Usage 2015/16 (millions) |

Branches and loops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London St Pancras | St Pancras, London | 1868 | 15 | High Speed 1 diverges north of St Pancras | |||

| Kentish Town | Kentish Town, London | 1868 | 4 | Branch from to Gospel Oak to Barking line north of station | |||

| West Hampstead Thameslink | West Hampstead, London | 1871 | 4 | ||||

| Cricklewood | Cricklewood, London | 1868 | 4 | Dudding Hill Line diverges north of Cricklewood | |||

| Hendon | Hendon, London | 1868 | 4 | Dudding Hill Line diverges south of Hendon | |||

| Mill Hill Broadway | Mill Hill, London | grid reference TQ213918 | 1868 | 4 | |||

| Elstree & Borehamwood | Borehamwood, Hertfordshire | 1868 | 4 | ||||

| Radlett | Radlett, Hertfordshire | grid reference TQ164998 | 1868 | 4 | |||

| St Albans City | St Albans, Hertfordshire | grid reference TL155070 | 1868 | 4 | |||

| Harpenden | Harpenden, Hertfordshire | grid reference TL137142 | 1868 | 4 | |||

| Luton Airport Parkway | Luton, Bedfordshire | grid reference TL105205 | 1999 | 4 | |||

| Luton | Luton, Bedfordshire | grid reference TL092216 | 1868 | 5 | |||

| Leagrave | Leagrave, Luton, Bedfordshire | grid reference TL061241 | 1868 | 4 | |||

| Harlington | Harlington, Bedfordshire | grid reference TL034303 | 1868 | 4 | |||

| Flitwick | Flitwick, Bedfordshire | grid reference TL034350 | 1870 | 4 | |||

| Bedford Midland | Bedford, Bedfordshire | grid reference TL041497 | 1859 | 5 | Marston Vale line diverges south of Bedford | ||

| Wellingborough | Wellingborough, Northamptonshire | grid reference SP903681 | 1857 | 3 | |||

| Kettering | Kettering, Northamptonshire | grid reference SP863780 | 1857 | 4 | Oakham–Kettering line diverges north of Kettering at Glendon Jun | ||

| via Corby & diversion route | |||||||

| Corby | Corby, Northamptonshire | grid reference SP891886 | 2009 | 1 | Oakham–Kettering line | ||

| Oakham | Oakham, Rutland | grid reference SK856090 | 1848 | 2 | Birmingham–Peterborough line | ||

| Melton Mowbray | Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire | grid reference SK752187 | 1848 | 2 | |||

| Main Line via Market Harborough | |||||||

| Market Harborough | Market Harborough, Leicestershire | grid reference SP741874 | 1850 | 2 | |||

| Leicester | Leicester, Leicestershire | grid reference SK593041 | 1840 | 4 | Birmingham to Peterborough Line diverges south of Leicester at Wigston Junction | ||

| Syston | Syston, Leicestershire | grid reference SK621111 | 1994 | 1 | Birmingham to Peterborough Line diverges north of Syston | ||

| Sileby | Sileby, Leicestershire | grid reference SK602151 | 1994 | 2 | |||

| Barrow-upon-Soar | Barrow-upon-Soar, Leicestershire | grid reference SK577172 | 1994 | 2 | |||

| Loughborough | Loughborough, Leicestershire | grid reference SK543204 | 1872 | 3 | |||

| East Midlands Parkway | Ratcliffe-on-Soar, Nottinghamshire (for East Midlands Airport) | grid reference SK496296 | 2007 | 4 | Trent Junction to Clay Cross Junction via Derby (the original line), the Nottingham branch, and the Erewash Valley Line each diverge north of East Midlands Parkway | ||

| Via Derby | |||||||

| Long Eaton | Long Eaton, Derbyshire | grid reference SK481321 | 1888 | 2 | Cord south of Long Eaton to the Nottingham branch | ||

| Spondon | Spondon, Derby, Derbyshire | grid reference SK397351 | 1839 | 2 | |||

| Derby | Derby, Derbyshire | grid reference SK362355 | 1839 | 6 | Cross Country Route and Crewe to Derby Line diverges south of Derby | ||

| Duffield | Duffield, Derbyshire | grid reference SK345435 | 1841 | 3 | |||

| Belper | Belper, Derbyshire | grid reference SK348475 | 1840 | 2 | |||

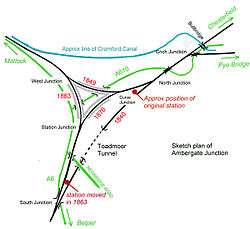

| Ambergate | Ambergate, Derbyshire | grid reference SK348516 | 1840 | 1 | Derwent Valley line diverges at Ambergate Junction | ||

| Via Nottingham | |||||||

| Attenborough | Attenborough, Nottinghamshire | grid reference SK518346 | 1856 | 2 | |||

| Beeston | Beeston, Nottinghamshire | grid reference SK533362 | 1839 | 2 | |||

| Nottingham Midland | Nottingham, Nottinghamshire | grid reference SK574392 | 1904 | 7 | Northbound trains reverse towards Langley Mill. Others pass through the station onto the Robin Hood Line, Grantham line or Lincoln line. | ||

| Via Erewash Valley (bypassing or calling at Nottingham) | |||||||

| Ilkeston | Ilkeston, Derbyshire | 2017 | 2 | ||||

| Langley Mill | Langley Mill, Derbyshire | grid reference SK449470 | 1847 | 2 | Erewash Valley and Trent Nottingham lines rejoin south of Langley Mill. | ||

| Alfreton | Alfreton, Derbyshire | grid reference SK422561 | 1862 | 2 | |||

| Clay Cross Junction to Leeds | |||||||

| Chesterfield | Chesterfield, Derbyshire | grid reference SK388714 | 1840 | 3 | Trent Junction to Clay Cross via Derby and Erewash Valley lines rejoin together south of Chesterfield. | ||

| Dronfield | Dronfield, Derbyshire | grid reference SK354784 | 1981 | 2 | Hope Valley line diverges north of Dronfield | ||

| Sheffield | Sheffield, South Yorkshire | grid reference SK358869 | 1870 | 9 | Hope Valley Line diverges south of Sheffield Sheffield to Lincoln Line diverges north of Sheffield | ||

| Meadowhall Interchange | Sheffield, South Yorkshire | grid reference SK390912 | 1990 | 4 NR | Hallam and Penistone Lines diverges at Meadowhall | ||

| Via Doncaster | |||||||

| Doncaster | Doncaster, South Yorkshire | grid reference SE571032 | 1838 | 8 | Connects to the East Coast Main Line south of Doncaster | ||

| Bypassing Doncaster | |||||||

| Wakefield Westgate | Wakefield, West Yorkshire | grid reference SE327207 | 1867 | 2 | Connects with the East Coast Main Line south of Wakefield Westgate | ||

| Leeds | Leeds, West Yorkshire | grid reference SE299331 | 1938 | 17 | Leeds City lines |

Tunnels, viaducts and major bridges

Major civil engineering structures on the Midland Main Line include the following.[58][59]

| Railway Structure | Length | Distance from London St Pancras International | ELR | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Bank Tunnel | 80 yards (73 m) | 158 miles 05 chains – 158 miles 01 chains | TJC1 | South of Sheffield station |

| Bradway Tunnel | 1 mile 266 yards (1,853 m) | 153 miles 61 chains – 152 miles 49 chains | North of Dronfield station | |

| Unstone Viaduct (River Drone) | 6 chains (120 m) | 149 miles 75 chains – 149 miles 69 chains | Between Dronfield and Chesterfield stations | |

| Former Broomhouse Tunnel | ||||

| Whitting Moor Road Viaduct | 148 miles 45 chains | |||

| Alfreton Tunnel | 840 yards (770 m) | 135 miles 50 chains – 135 miles 11 chains (via Toton) | TCC | Erewash Valley Line between Alfreton and Langley Mill stations |

| Cromford Canal | 132 miles 67 chains (via Toton) | |||

| Erewash Canal | 128 miles 09 chains (via Toton) | Erewash Valley Line south of Langley Mill station | ||

| Clay Cross Tunnel | 1 mile 24 yards (1,631 m) | 147 miles 22 chains – 146 miles 21 chains | SPC8 | Between Chesterfield and Belper stations |

| River Amber | 140 miles 40 chains | |||

| Wingfield Tunnel | 261 yards (239 m) | 139 miles 59 chains – 139 miles 47 chains | ||

| Toadmoor Tunnel | 129 yards (118 m) | 138 miles 12 chains – 138 miles 07 chains | ||

| River Derwent / Broadholme Viaducts | 6 chains (120 m), 7 chains (140 m) |

136 miles 47 chains – 136 miles 41 chains, 136 miles 18 chains – 136 miles 11 chains | ||

| Swainsley Viaduct (River Derwent) | 4 chains (80 m) | 134 miles 61 chains – 134 miles 57 chains | Between Belper and Duffield stations | |

| Milford Tunnel | 855 yards (782 m) | 134 miles 25 chains – 133 miles 67 chains | ||

| Burley Viaduct (River Derwent) | 4 chains (80 m) | 131 miles 58 chains – 131 miles 54 chains | Between Duffield and Derby stations | |

| Nottingham Road Viaduct | 3 chains (60 m) | 128 miles 43 chains – 128 miles 40 chains | ||

| River Derwent Viaduct | 3 chains (60 m) | 128 miles 06 chains – 128 miles 03 chains | ||

| Trent Viaduct | 11 chains (220 m) | 119 miles 08 chains – 118 miles 77 chains | SPC6 | Between Long Eaton and East Midlands Parkway station |

| Redhill Tunnels | 154 yards (141 m), 170 yards (160 m) |

118 miles 74 chains – 118 miles 66 chains | ||

| River Soar | 112 miles 74 chains | SPC5 | Between East Midlands Parkway and Loughborough stations | |

| Flood openings | 2 chains (40 m) | 112 miles 60 chains – 112 miles 58 chains | ||

| Hermitage Brook Flood Openings | 3 chains (60 m) | 111 miles 41 chains – 111 miles 38 chains | South of Loughborough station | |

| River Soar | 109 miles 55 chains | North of Barrow-upon-Soar station | ||

| River Wreak | 104 miles 60 chains | South of Sileby station | ||

| Knighton Tunnel | 104 yards (95 m) | 98 miles 07 chains – 98 miles 02 chains | SPC4 | South of Leicester station |

| Knighton Viaduct | 4 chains (80 m) | 97 miles 34 chains – 97 miles 30 chains | ||

| Wellingborough Viaducts (River Ise) | 6 chains (120 m) | 64 miles 57 chains – 64 miles 51 chains | SPC2 | South of Wellingborough station |

| Irchester Viaducts (River Nene) | 7 chains (140 m) | 63 miles 67 chains – 63 miles 60 chains | ||

| Sharnbrook Tunnel (Slow line only) | 1 mile 100 yards (1,701 m) | 60 miles 04 chains – 59 miles 00 chains | WYM | Between Wellingborough and Bedford stations |

| Sharnbrook Viaducts | 9 chains (180 m) | 56 miles 25 chains – 56 miles 16 chains | SPC2 | |

| Radwell Viaducts | 143 yards (131 m) | 55 miles 03 chains – 54 miles 76½ chains | ||

| Milton Ernest Viaducts | 8 chains (160 m) | 54 miles 25 chains – 54 miles 17 chains | ||

| Oakley Viaducts | 6 chains (120 m) | 53 miles 35 chains – 53 miles 29 chains | ||

| Clapham Viaducts (River Ouse) | 6 chains (120 m) | 52 miles 04 chains – 51 miles 78 chains | ||

| Bromham Viaducts (River Ouse) | 7 chains (140 m) | 50 miles 79 chains – 50 miles 72 chains | ||

| River Great Ouse Viaduct | 5 chains (100 m) | 49 miles 38 chains – 49 miles 33 chains | SPC1 | Between Bedford and Flitwick stations |

| Ampthill Tunnels | 715 yards (654 m) | 42 miles 52 chains – 42 miles 19 chains | ||

| Hyde/Chiltern Green Viaduct (River Lea) | 6 chains (120 m) | 26 miles 72 chains – 26 miles 66 chains | South of Luton Airport Parkway station | |

| Elstree Tunnels | 1,058 yards (967 m) | 12 miles 06 chains – 11 miles 38 chains | South of Elstree & Borehamwood station | |

| Stoneyfield/Deans Brook Viaduct | 4 chains (80 m) | 10 miles 36 chains – 10 miles 32 chains | Between Elstree & Borehamwood and Hendon stations | |

| Welsh Harp/Brent Viaduct (River Brent) | 10 chains (200 m) | 6 miles 31 chains – 6 miles 21 chains | South of Hendon station | |

| Belsize Slow Tunnel | 1 mile 107 yards (1,707 m) | 3 miles 34 chains – 2 miles 29 chains | Between West Hampstead Thameslink and Kentish Town stations | |

| Belsize Fast Tunnel | 1 mile 11 yards (1,619 m) | 3 miles 32 chains – 2 miles 33 chains | ||

| Lismore Circus Tunnel[60] | 110 yards (100 m) | 2 miles 22 chains – 2 miles 17 chains | ||

| Hampstead Tunnel | 44 yards (40 m) | 1 mile 76 chains – 1 mile 74 chains | ||

| Camden Road Tunnels | 308 yards (282 m) | 1 miles 13 chains – 0 miles 79 chains | South of Kentish Town station | |

| Canal Tunnels | 820 yards (750 m) | 0 miles 0 chains – 0 miles 0 chains | Connecting to ECML at Belle Island Junction |

Line-side monitoring equipment

Line-side train monitoring equipment includes hot axle box detectors (HABD) and wheel impact load detectors (WILD) ‘Wheelchex’, these are located as follows.[59][61][58]

| Name / Type | Line | Location (distance from St. Pancras) | Engineers Line Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dore HABD (out of use?) | Down Main | 154 miles 72 chains | TJC1 |

| Belper HABD (to replace Duffield HABD) | Up Main | 134 miles 70 chains | SPC8 |

| Duffield Junction HABD (removal planned) | Up Main | 132 miles 63 chains | |

| Langley Mill HABD | Up Erewash Fast, Up & Down Erewash Slow | 129 miles 27 chains | TCC |

| Loughborough HABD | Up Fast, Up Slow | 111 miles 05 chains | SPC5 |

| Barrow-upon-Soar HABD | Down Fast, Down Slow | 108 miles 72 chains | |

| Thurmaston Wheelchex | Down Fast, Up Fast, Up & Down Slow | 101 miles 78 chains | |

| East Langton HABD | Down Main, Up Main | 86 miles 20 chains | SPC3 |

| Harrowden Junction HABD | Down Fast, Up & Down Slow | 67 miles 36 chains | |

| Oakley HABD | Up Fast, Up Slow | 53 miles 60 chains | SPC2 |

| Chiltern Green HABD | Down Fast, Down Slow | 27 miles 69 chains | SPC1 |

| Napsbury HABD | Up Fast, Up Slow | 18 miles 00 chains |

Ambergate Junction to Manchester

For marketing and franchising, this is no longer considered part of the Midland Main Line: see Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway

The line was once the Midland Railway's route from London St Pancras to Manchester, branching at Ambergate Junction along the Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway, now known as the Derwent Valley line. In days gone by, it featured named expresses such as The Palatine. Much later in the twentieth century, it carried the Midland Pullman.

| Town/City | Station | Ordnance Survey grid reference |

|---|---|---|

| Ambergate | Ambergate | |

| Whatstandwell | Whatstandwell | |

| Cromford | Cromford | |

| Matlock Bath | Matlock Bath | |

| Matlock | Matlock | |

| Closed section stations | ||

| Darley Dale | Darley Dale | |

| Rowsley | Rowsley | |

| Bakewell | Bakewell | |

| Hassop | Hassop | |

| Great Longstone | Great Longstone for Ashford | |

| Monsal Dale | Monsal Dale | |

| Millers Dale | Millers Dale | |

| Blackwell Mill | Blackwell Mill | |

| Buxton | Buxton | |

| Peak Forest | Peak Forest | |

| Chapel-en-le-Frith | Chapel-en-le-Frith Central | |

| Now part of the Hope Valley line or other lines | ||

| Chinley | Chinley | |

| Bugsworth | Buxworth (Now Closed) | |

| New Mills | New Mills Central | |

| Strines | Strines | |

| Marple | Marple | |

| Romiley | Romiley | |

| Bredbury | Bredbury | |

| Brinnington | Brinnington | |

| Reddish | Reddish North | |

| Gorton | Ryder Brow | |

| Belle Vue/Gorton | Belle Vue | |

| Stockport | Stockport Tiviot Dale | |

| Manchester | Manchester Central (Now Closed) |

This line was closed in the 1960s between Matlock and Buxton, severing an important link between Manchester and the East Midlands, which has never been satisfactorily replaced by any mode of transport. A section of the route remains in the hands of the Peak Rail preservation group, operating between Matlock and Rowsley to the north.

Leeds to Carlisle

For marketing and franchising, this is no longer considered part of the Midland Main Line: see Settle–Carlisle Railway.

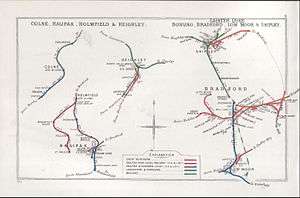

World War I prevented the Midland Railway from finishing its direct route through the West Riding to join the Settle and Carlisle (which would have cut six miles from the journey and avoided the need for reversal at Leeds).

The first part of the Midland's West Riding extension from the main line at Royston (Yorks.) to Dewsbury was opened before the war. However, the second part of the extension was not completed. This involved a viaduct at Dewsbury over the River Calder, a tunnel under Dewsbury Moor and a new approach railway into Bradford from the south at a lower level than the existing railway (a good part of which was to be in tunnel) leading into Bradford Midland (or Bradford Forster Square) station.

The 500 yards (460 m) gap between the stations at Bradford still exists. Closing it today would also need to take into account the different levels between the two Bradford stations, a task made easier in the days of electric rather than steam traction, allowing for steeper gradients than possible at the time of the Midland's proposed extension.

Two impressive viaducts remain on the completed part of the line between Royston Junction and Dewsbury as a testament to the Midland's ambition to complete a third direct Anglo-Scottish route. The line served two goods stations and provided a route for occasional express passenger trains before its eventual closure in 1968.

The failure to complete this section ended the Midland's hopes of being a serious competitor on routes to Scotland and finally put beyond all doubt that Leeds, not Bradford, would be the West Riding's principal city. Midland trains to Scotland therefore continued to call at Leeds before travelling along the Aire Valley to the Settle and Carlisle. From Carlisle they then travelled onwards via either the Glasgow and South Western or Waverley Route. In days gone by the line enjoyed named expresses such as the Thames–Clyde Express and The Waverley.

- Leeds along the Airedale line

- Here is Apperley Junction for the Wharfedale line

- Shipley: here is the triangular junction for the branch line serving Bradford Forster Square

- Saltaire

- Bingley

- Crossflatts

- Keighley

- Here is the Worth Valley Branch junction to Oxenhope.

- Steeton & Silsden

- Cononley

- Skipton

- Here is Settle Junction for the line to Morecambe

- Giggleswick

- Clapham

- Here was the junction for Ingleton and an end-on junction via Sedbergh to Low Gill on the London and North Western Railway (LNW) West Coast Main Line

- Bentham

- Lancaster Green Ayre

- At this point the line divided: a triangular junction for the two lines:

- Morecambe

- Heysham Port, including a station for Middleton Road Heysham

- At this point the line divided: a triangular junction for the two lines:

- Here is Settle Junction for the line to Morecambe

- Settle

- Horton-in-Ribblesdale

- Ribblehead

- Dent

- Garsdale

- At Hawes station, on the branch to the east of the main line, there was an end-on junction with the North Eastern Railway (NER) line across the Pennines to Northallerton

- Kirkby Stephen

- Appleby

- Langwathby

- Armathwaite

- Cumwhinton

- Carlisle

Former stations

As with most railway lines in Britain, the route used to serve far more stations than it currently does (and consequently passes close to settlements that it no longer serves). Places that the current main line used to serve include

- London to Leicester

- Camden Road

- Haverstock Hill

- Finchley Road

- Welsh Harp

- Napsbury

- Chiltern Green

- Ampthill

- Oakley

- Sharnbrook

- Irchester

- Finedon

- Isham and Burton Latimer

- Glendon and Rushton

- Desborough

- East Langton

- Kibworth

- Great Glen

- Wigston Magna

- Leicester to Trent Junction

- Leicester Humberstone Road

- Cossington Gate

- Hathern

- Kegworth

- Trent

- Derwent Valley

- Breaston (later Sawley – see Long Eaton)

- Draycott

- Borrowash

- Derby Nottingham Road

- Wingfield

- Stretton

- Clay Cross

- Erewash Valley

- Long Eaton (Original Midland Counties Railway station not the present one)

- Stapleford and Sandiacre

- Stanton Gate

- Trowell

- Ilkeston Junction and Cossall- reopened as Ilkeston

- Shipley Gate

- Codnor Park and Ironville

- Pye Bridge

- Westhouses and Blackwell

- Doe Hill

- Chesterfield to Leeds

- Staveley

- Eckington and Renishaw

- Killamarsh West

- Beighton

- Woodhouse Mill

- Treeton

- Sheepbridge

- Unstone

- Beauchief

- Millhouses

- Heeley

- Attercliffe Road

- Brightside

- Holmes

- Rotherham Masborough

- Parkgate and Rawmarsh

- Kilnhurst

- Swinton West (reopened Swinton)

The following on the original North Midland Railway line

- Wath North

- Darfield

- Cudworth

- Royston and Notton

- Oakenshaw (originally for Wakefield)

- Normanton

- Methley North

- Woodlesford - station still open

Looking south along the Midland Main Line at St Albans

Looking south along the Midland Main Line at St Albans The Erewash Valley Line, part of the Midland Main Line. Seen here at Stapleford

The Erewash Valley Line, part of the Midland Main Line. Seen here at Stapleford

Leeds railway station, a former key reversal point on the Midland Main Line on the route north

Leeds railway station, a former key reversal point on the Midland Main Line on the route north

See also

- Great Central Main Line – Former competing main line

Notes and references

- Notes

- Quickly the Sheffield and Rotherham Railway ran its branch line to Sheffield Wicker

- References

- "East Midlands RUS Loading Gauge" (PDF). Network Rail. p. 55. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- "Route 19 Midland Main Line and East Midlands" (PDF). Archived from the original (pdf) on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- "The Railway between Nottingham and Derby". Stamford Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 7 June 1839. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "Midland Counties Railway". Leicester Chronicle. British Newspaper Archive. 9 May 1840. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "A Midland Railway chronology>Incorporation and expansion". The Midland Railway Society. 1998. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Leleux, Robin. A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain. Volume 9. David & Charles, Newton Abbot. p. 92. ISBN 0715371657.

- "Opening of the Leicester and Hitchin Line". Bedfordshire Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 9 May 1857. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- Davies, R.; Grant, M.D. (1984). Forgotten Railways: Chilterns and Cotswolds. Newton Abbot, Devon: David St John Thomas. ISBN 0-946537-07-0, p. 110-111.

- "A Midland Railway chronology>London extension". The Midland Railway Society. 1998. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008.

- Barnes, E. G. (1969). The Rise of the Midland Railway 1844–1874. Augustus M. Kelley, New York. p. 308.

- Radford, B., (1983) Midland Line Memories: a Pictorial History of the Midland Railway Main Line Between London (St Pancras) & Derby London: Bloomsbury Books

- Railway Magazine June 1958. p. 432.

- Railway Electrification. British Railways Board (Central Publicity Unit). Winter 1979. pp. 0–2, 8.

- "East Midlands Parkway – Our greenest station to open on 26 January" (Press release). East Midlands Trains. 14 January 2009.

- "Midland Main Line celebrates at 125mph". Rail News. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- "Route Utilisation Strategy > Freight". Network Rail.

- "Midland Main Line / East Midlands Route Utilisation Strategy". Strategic Rail Authority. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- "East Midlands Route Utilisation Strategy". Network Rail. February 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- "Midlands line 'to be electrified'". BBC News Online. 14 July 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

A £500m scheme … Transport Secretary Justine Greening is set to outline plans to complete the electrification of the route from Sheffield to London on Monday.

- Odell, Mark; Parker, George (13 July 2012). "Osborne backs £10bn rail plan". Financial Times. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

announcement, expected on Monday, is likely to include a £530m plan to complete electrification of the Midland mainline between Bedford and Sheffield

- "Working Group 4 – Electrification Strategy". Network Rail. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- Barton, Tom (17 March 2014). "Developers taking too long to build homes, MP says". BBC News Online. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- "Kettering East: Compromise deal agreed over funding". BBC News Online. 13 March 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Broadbent, Steve (19 February 2014). "Switching on the Electric Spine". RAIL. No. 742. pp. 69–75.

- "Midland Main Line 2010 route plan" (PDF). Network Rail. Network Rail. 2010. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- "Secretary of State opens Network Rail control centre" (Press release). Network Rail. Archived from the original on 26 September 2008. Retrieved 29 August 2008.

- "Plans for £150m station facelift". BBC News Online. London. 6 March 2008.

- Department for Transport (26 July 2011). "Access for all – stations". GOV.UK. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- Rail Magazine. Issue 742. 19 February – 4 March. pp. 69–75.

- "Second Corby to Kettering railway track to be restored". BBC News Online. London. 6 February 2014.

- "Investing in rail, investing in jobs and growth" (Press release). Department for Transport. 16 July 2012. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- "Network Rail to spend £500m electrifying Midland Mainline". BBC News. 8 January 2013.

- Rail Magazine. issue 729. 2013. p. 6.

- Network Rail: East Midlands Draft Route Utilisation Strategy. Retrieved 23 August 2013

- "Today's House of Commons debates – Thursday 25 June 2015: Network Rail". UK Parliament. Retrieved 25 June 2015.

- "TransPennine and Midland Mainline electrification works to resume" (Press release). Department for Transport. 30 September 2015.

- "Electrification of train lines to be restarted by Network Rail". BBC News. 30 September 2015.

- "Sheffield, Swansea and Windermere electrification cancelled". Railway Gazette. 20 July 2017.

- "HS2 Update". Hansard Online. 627. 17 July 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- "Network Rail awards MML electrification and upgrade contract". Global Rail News. 6 November 2017.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Electrification to reach Market Harborough". Railway Gazette. 5 March 2019.

- "Wellingborough railway station expansion plan unveiled". BBC News. 18 April 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "Wait finally over for Ilkeston train station as hundreds turn up to opening". Nottingham Post. 2 April 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Brent Cross Cricklewood: Transport Archived 29 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 23 August 2013

- The Wixams: Transportation Archived 17 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 23 August 2013

- "Route Specifications 2015 - London North Eastern and East Midlands" (PDF). Network Rail. Network Rail. April 2015. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- "Connecting Communities – Expanding Access to the Rail Network" (PDF). London: Association of Train Operating Companies. June 2009. p. 9. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ATOC 2009, p. 19.

- Bedfordshire Ampthill station Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Railway & Transport Association. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- Bradshaw, George (1848). Bradshaw’s railway almanack, directory, shareholders’ guide and manual. George Bradshaw. p. 204.

- "The Leeds and Bradford". Derby Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 15 August 1849. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "The New Works of the Midland Railway Company". Birmingham Journal. British Newspaper Archive. 21 December 1867. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- "The New Midland Railway Station at Sheffield". Sheffield Independent. 12 December 1868. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- First Capital Connect: Thameslink Route Timetable B Archived 26 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 24 August 2013

- "New cutting-edge trains in full operation across Thameslink route". mynewsdesk.com. Mynewsdesk. 18 September 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- Bridge, Mike (2013). Railway Track Diagrams Book 4 Midlands & North West. Bradford on Avon: Trackmaps. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-9549866-7-4.

- Brailsford, Martyn (2016). Railway Track Diagrams Book 2: Eastern. Frome: Trackmaps. pp. 1, 27. ISBN 978-0-9549866-8-1.

- "London North Eastern Route Sectional Appendix; LOR LN3201 Seq001 to 030" (pdf). Network Rail. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- "Railway Codes: HABD and WILD equipment".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Midland Main Line. |