Bus transport in the United Kingdom

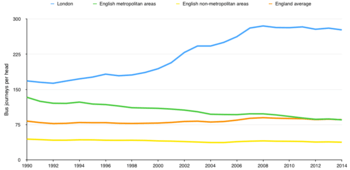

Buses play a major role in the public transport of the United Kingdom, as well as seeing extensive private use. While rail transport has increased over the past twenty years due to road congestion, the same does not apply to buses, which have generally been used less, apart from in London where their use has increased significantly. Bus transport is heavily subsidised, with subsidy accounting for around 45 per cent of operator revenue,[1] especially in London.[2]

In 2014/15, there were 5.2 billion bus journeys in the UK, 2.4 billion of which were in London.[3] The UK bus network has shrunk by 8% over the past decade due to government subsidy cuts and a reduction in commercial operations in the north of England.[4]

History

The horse bus era

The first omnibus service in the United Kingdom was started by John Greenwood between Pendleton and Manchester in 1824. Stagecoach services, sometimes over short distances, had existed for many years. Greenwood's innovation was to offer a service which did not require booking in advance, and which picked up and set down passengers en route. Greenwood did not use the term omnibus, which was first used in France in 1826.

In 1829 George Shillibeer started the first omnibus service in London. Over the next few decades, horse bus services developed in London, Manchester and other cities. They became bigger, and double deck buses were introduced in the 1850s. The growth of suburban railways, and later horse trams (from 1860) and electric trams (from 1885) changed the patterns of horse bus services, but horse buses continued to flourish. By 1900 there were 3,676 horse buses in London.[5]

The first motor buses

There were experiments with steam buses in the 1830s,[6] but harsh legislation in 1861 virtually eliminated mechanically propelled road transport from Britain until the law was changed in 1896.[7] From 1897 various experimental motor bus services were operated with petrol-driven vehicles, including a service in Edinburgh which ran from 1898 to 1901. In 1903 motor bus services were started in Eastbourne, and in the same year a motor bus service was started between Helston and The Lizard by the Great Western Railway .

Motor bus services grew quickly, and soon eclipsed the horse buses. Early operators were the tramway companies, e.g. the British Electric Traction Company, and the railway companies. In London, the horse bus companies, the London General Omnibus Company and Thomas Tilling, introduced motor buses in 1902 and 1904, and the National Steam Car Company started steam bus services in 1909. By the time of the First World War, BET had begun to emerge as a national force.[8]

Between the wars

By the time of the First World War, the LGOC had achieved dominance in London, and its two major competitors, Tilling and National (in 1919 renamed National Omnibus and Transport Company) looked elsewhere for expansion. After the war, many bus companies were started by ex-servicemen who had learnt mechanics in the Army. The 1920s were an era of intense competition, but BET, Tilling and National gradually acquired more companies. Tilling had shares in BET as well as competing with BET, and in 1928 the two companies formed Tilling & British Automobile Traction Co., which continued its acquisitions. At the end of the 1920s the railways mostly ceased direct bus operation, but acquired interests in many bus companies. The National transferred its operations to three companies jointly owned with the railways, Eastern National, Southern National and Western National.

The Road Traffic Act 1930 ended the period of competition and introduced a new system of regulation of bus services. One effect was to eliminate many of the smaller operators. In 1931, Tilling acquired control of the National. In England outside London and towns where municipalities ran their own buses, the industry was dominated by Tilling, BET and their joint company TBAT. In Scotland, Scottish Motor Traction came to be the dominant force.

In London, including the surrounding area up to 30 miles from London, bus services were effectively nationalised in 1933, when operations were compulsorily transferred to the new London Passenger Transport Board.

In 1942, TBAT was wound up, and its companies transferred to Tilling.

Nationalisation

The post-war Labour government embarked on a programme of nationalisation of transport. Under the Transport Act 1947, the British Transport Commission acquired the bus services of Thomas Tilling, Scottish Motor Traction and the large independent Red & White. By the nationalisation of the railways, the BTC also acquired interests in many of BET's bus companies, but BET was not forced to sell its companies and they were not nationalised.

In 1962 the BTC's bus companies were transferred to the Transport Holding Company. Then in 1968 BET sold its UK bus companies to the Transport Holding Company. Almost all of the UK bus industry was by then owned by the government or by municipalities.

Bus passenger numbers declined in the 1960s. The Transport Act 1968 was an attempt to rationalise publicly owned bus services and provide a framework for the subsidy of uneconomic but socially necessary services. The Act:

- transferred the English and Welsh bus companies of the Transport Holding Company to the new National Bus Company

- transferred the country services of London Transport to the NBC.

- transferred the Scottish bus companies of the THC to the Scottish Transport Group

- transferred municipal bus operations in the 5 large metropolitan areas outside London to new Passenger Transport Executives, together with some operations of THC companies in those areas.

Privatisation

.jpg)

In 1980 the new Thatcher government embarked on a programme of deregulation and privatisation of bus services. The National Bus Company and Scottish Transport Group divided some of their larger subsidiaries into more saleable units. In 1986, under the Transport Act 1985, all bus services apart from those in London and Northern Ireland were deregulated. The NBC's and STG's subsidiaries were then sold, in most cases to their management and employees.

Bus services in London were transferred to a new company, London Buses in 1984, split into smaller companies in 1989 and then privatised. The PTEs were also required to sell their bus operations. Local authorities had to transfer their buses to arms length companies, some of which (but not all) were sold off.

Post deregulation, the intended model had been for competition between private companies to increase services. Regulations prevented neighbouring state owned companies being sold to the same concern, to create a 'patch-work' distribution of the operating areas. Competition law prevented private companies acquiring more than a certain percentage of geographical market share.

Competition did occur in many areas, in some cases causing bus wars. However, many of the smaller start up operators were bought up by their larger neighbours after a few years. After some initial mergers, five large bus groups emerged - two (FirstGroup and Go-Ahead Group) were formed from NBC bus companies sold to their managements, two (Stagecoach and Arriva) were independent companies which pursued aggressive acquisition policies, and National Express was the privatised coach operator which diversified into bus operation.

There were few cases of long term competition. As competition often occurs on frequency, resulting in a period of loss making competition, where both operators operate a high frequency, ending with an operator leaving the route.[9]

In the early 1990s it seemed all services would fall into the hands of the few major groups, but recent trends have seen the disposal of relatively large companies where revenues do not meet shareholder expectations. The Stagecoach Group went so far as to dispose of its two large London operations, citing the inability to grow the business within the London regulated structure.[10] They later repurchased their London operations in 2010, after it entered administration.[11]

Some large overseas groups have also entered the UK bus market, such as Transit Systems, who purchased First's London operations, under the Tower Transit name,[12] and ComfortDelGro, who own Metroline, and recently purchased New Adventure Travel

Regulation

Today, bus service provision for public transport in the UK is regulated in a variety of ways. Bus transport in London is regulated by Transport for London.[13] Bus transport in some large conurbations is regulated by Passenger Transport Executives.[14] Bus transport elsewhere in the country must meet the requirements of the local Traffic Commissioner, and run to their registered service. Under the free market, the barriers to entry into public bus service operation is aimed to be as low as possible.

Operators of service buses and coaches (PSVs) must hold an operating licence (an 'O' licence). Under an O licence, operators are registered with the Vehicle and Operator Services Agency (VOSA) under a company name, and if applicable, any trading names, and are allocated a maximum fleet size allowed to be stored at nominated operating centres. An O licence is required for each of the 8 national Traffic Areas in which an operator has an operating centre. Reducing the vehicle allocation on, or revoking, an O licence can occur if an operator is found to be operating in contravention of any laws or regulations.[15]

In Northern Ireland, coach, bus (and rail) services remain state-owned and are provided by Translink.[16]

Using the example of bus passenger growth seen in London under the changes made by Transport for London, several parties have advocated a return to increased regulation of bus services along the London model.

The Transport Act 2000 made certain provisions for increased cooperation between local authorities and bus operators to take measures to improve services, such cooperation was previously barred under competition law. Under the act, Quality Bus Partnerships were enabled, although this had limited success. In Sheffield the first Statutory Quality Partnership was introduced along the Barnsley Road corridor, shortly followed in Barnsley with a Partnership introduced covering the A61 (north) and the new Barnsley Interchange. In Cardiff, the Statutory Quality Bus Partnership has also been used, with the introduction of new buses on Cardiff Bus routes. The Act also included measures allowing the registration of variable route services, as demand responsive transport.

In 2004, regulations were amended to further allow fully flexible demand responsive transport bus services.[17]

Changes to regulations regarding bus operation are proposed in the 2007 Local Transport Bill.

Operating companies

While most bus operating companies are private, some are operated as community based or not for profit entities, or as local authority arms length companies, as municipal bus companies.

The majority of bus services in both urban and rural areas are now run by subsidiaries of a few major bus groups, many of which also hold the franchises to many train operating companies and light rail systems.

Subsidies

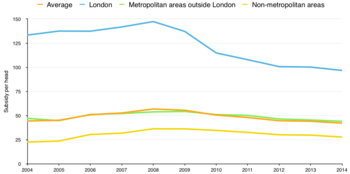

For 2014/15, subsidies (including the cost of concessionary fares) in England were £2.3 billion, made up of £826 million for London, £516 million for metropolitan areas outside London and £951 million for non-metropolitan areas.[3] In Scotland, they were £291 million for 2013/14.[18]

Types in use

Historically, full size single and double-decker buses formed the mainstay of the UK bus fleet.

In the 1980s, minibuses were developed from so-called, 'van-derived' minibus chassis, such as the Ford Transit and the Freight Rover Sherpa. As their popularity increased, designs have become more bus focused, with the numerous Mercedes-Benz models.

Following abortive purpose built designs such as the Bedford JJL, and the limited use of shortened chassis such as the Seddon Pennine and Dennis Domino, the Dennis Dart introduced the concept of the midibus to the UK operating market in large numbers in the 1990s. Beginning as a short wheelbase bus, some midibus designs have become as long as full size buses.

Developments such as the Optare Solo have further blurred the distinctions between mini and midi buses.

Since the mid-1990s, all bus types have had to come into line with Easy Access regulations, with the most notable change being the introduction of low-floor technology. As of February 2008, 58% of the UK's bus fleet was low floor.[19]

Apart from a brief experiment in the 1980s in Sheffield, with the Leyland-DAB, articulated buses (artics), had not gained a foothold in the UK market. In the new millennium, artics were introduced in various parts of the UK, following a controversial initial introduction in London. However, the London artics had all been withdrawn by 2011.

Services

Aside from normal urban and inter-urban services, bus transport in the UK also has a number of niche uses:

- Express services

- Park and Ride services

- School bus services

- Hail and Ride services

- Demand responsive transport services

- Long distance coach services

- Zero-fare services

Park and Ride

Buses play an integral role in park and ride schemes in the UK, with operations across the country, having been implemented in volume since the 1980s and 1990s. Schemes now range in size from small standard liveried buses, to large dedicated route branded fleets. The majority are permanent, government supported public transport schemes, although operating contracts must be competitively tendered. Some schemes branded park and ride are for private use, such as airport buses. Others cater for specific events or segments of passengers, such as National Health Service staff.

Private uses

Private use of bus transport in the United Kingdom encompasses tour buses, vehicles for hire, and holiday excursions/package tours.

Preservation

Interest in preservation of historical buses is maintained in the UK by various museums and heritage/preservation groups, ranging from attempts to restore a single bus, to whole collections. While many preserved buses are vintage, increasingly, 'modern' types, such as the Leyland National, and the Optare Spectra[20] are being preserved. With the fleet replacement of the major groups, it is not uncommon for many preserved buses to still have contemporary models still in service.

Manufacturers

Early UK bus manufacturers included private companies such as Guy Motors, Leyland Motors and AEC. Some bus operating companies, such as the London General Omnibus Company and Midland Red, also manufactured buses.

During nationalisation, two UK manufacturers fell under government ownership, Bristol Commercial Vehicles and Eastern Coach Works. Later, Leyland Bus was also effectively nationalised.

Before, and increasingly after privatisation, foreign manufacturers such as Scania entered the UK market, followed by the likes of Mercedes-Benz.

Current British bus manufacturers include Alexander Dennis, Optare and Wrightbus.

Bus rapid transit systems

Following the failure of some light rail proposals in some UK towns to gain national funding on the Department of Transport's value for money assessment, several towns have turned to enhanced bus services as a cheaper alternative. Following limited historical use, such as in Runcorn and Birmingham, the use of guided bus technology and bus rapid transit schemes has increased in the UK. Among these are the longest guided busway in the world, the Cambridgeshire Guided Busway which opened in 2011, and the Luton to Dunstable Busway, the second-longest guided busway, which opened in 2013.

Other busways in operation include Ipswich Rapid Transit, Crawley Fastway, South East Hampshire Bus Rapid Transit, Leigh-Salford-Manchester Bus Rapid Transit, and Bus Rapid Transit North, using a variety of technologies.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bus transport in the United Kingdom. |

References

- Butcher, Louise (4 December 2013). Buses: grants and subsidies. House of Commons Library.

- "Transport for London's budget deficit down but uncertainty looms". BBC. 20 March 2019.

- "Government bus statistics".

- "Britain's bus coverage hits 28-year low". BBC. 16 February 2016.

- "The Horse Bus 1662-1932 by Peter Gould". Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- See Walter Hancock and Sir Goldsworthy Gurney

- "The Steam Bus 1833-1923 by Peter Gould". Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- Early motor buses and bus services, by Peter Gould Archived 8 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Peat, Jeremy; Grey, Ivar; Hoehn, Thomas; Holmes, Katherine; Watson, Michael; Saunders, David (2011). Local bus services market investigation (PDF). Competition Commission. pp. 5–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Stewart, Steven (2006). "London bus sold off in £264m deal" (PDF). On Stage. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Fletcher, Nick (15 October 2010). "Stagecoach buys back London bus business at a discount". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Australian public transport innovator acquires first international fleet Archived 9 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Transit Systems

- "London Service Permits". TfL. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "Passenger Transport Executives | Office of Rail and Road". orr.gov.uk. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "Public Service Vehicle Operator Licensing : Guide for Operators" (PDF). VOSA. November 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "The Northern Ireland Transport Holding Company". Department for Infrastructure. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- Enoch, Marcus; Ison, Stephen; Laws, Rebecca; Zhang, Lian. "Evaluation Study of Demand Responsive Transport Services in Wiltshire" (PDF). Transport Studies Group, Loughborough University. p. 13. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- "Bus and coach travel statistics".

- Confederation of Passenger Transport

- "West Midlands Optare Spectra R1 NEG". Transport Museum Wythall. Retrieved 5 December 2018.