Peter Abelard

Peter Abelard (/ˈæb.ə.lɑːrd/; Latin: Petrus Abaelardus or Abailardus; French: Pierre Abélard, pronounced [a.be.laːʁ]; c. 1079 – 21 April 1142) was a medieval French scholastic philosopher, theologian, and preeminent logician.[4] His love for, and affair with, Héloïse d'Argenteuil has become legendary. The Chambers Biographical Dictionary describes him as "the keenest thinker and boldest theologian of the 12th century".[5]

Peter Abelard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1079 |

| Died | 21 April 1142 (age 62 or 63) Abbey of Saint-Marcel near Chalon-sur-Saône, France |

Notable work | Sic et Non |

| Era | 11th-century philosophy Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy French philosophy |

| School | Scholasticism Conceptualism |

Main interests | Metaphysics, logic, philosophy of language, theology |

Notable ideas | Conceptualism, Limbo Moral influence theory of atonement[1][2] |

Influenced

| |

Life

Youth

Abelard, originally called "Pierre le Pallet", was born c. 1079 in Le Pallet,[6] about 10 miles (16 km) east of Nantes, in Brittany, the eldest son of a minor noble French family. As a boy, he learned quickly. His father, a knight called Berenger, encouraged Pierre to study the liberal arts, wherein he excelled at the art of dialectic (a branch of philosophy), which, at that time, consisted chiefly of the logic of Aristotle transmitted through Latin channels. Instead of entering a military career, as his father had done, Abelard became an academic. During his early academic pursuits, Abelard wandered throughout France, debating and learning, so as (in his own words) "he became such a one as the Peripatetics."[7] He first studied in the Loire area, where the nominalist Roscellinus of Compiègne, who had been accused of heresy by Anselm, was his teacher during this period.[5]

Rise to fame

Around 1100, Abelard's travels finally brought him to Paris. In the great cathedral school of Notre-Dame de Paris (before the current cathedral was actually built), he was taught for a while by William of Champeaux, the disciple of Anselm of Laon (not to be confused with Saint Anselm), a leading proponent of Realism.[5] During this time he changed his surname to "Abelard", sometimes written "Abailard" or "Abaelardus". Retrospectively, Abelard portrays William as having turned from approval to hostility when Abelard proved soon able to defeat the master in argument;[lower-alpha 1] Abelard was, however, closer to William's thought than this account suggests[8] and William thought Abelard was too arrogant.[9] It was during this time that Abelard would provoke quarrels with both William and Roscellinus.[6] Against opposition from the metropolitan teacher, Abelard set up his own school, first at Melun, a favoured royal residence, then, around 1102–4, for more direct competition, he moved to Corbeil, nearer Paris.[7]

His teaching was notably successful, though for a time he had to give it up and spend time in Brittany, the strain proving too great for his constitution. On his return, after 1108, he found William lecturing at the hermitage of Saint-Victor, just outside the Île de la Cité, and there they once again became rivals, with Abelard challenging William over his theory of universals. Abelard was once more victorious, and Abelard was almost able to hold the position of master at Notre Dame. For a short time, however, William was able to prevent Abelard from lecturing in Paris. Abelard accordingly was forced to resume his school at Melun, which he was then able to move, from c. 1110-12, to Paris itself, on the heights of Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, overlooking Notre-Dame.[10]

From his success in dialectic, he next turned to theology and in 1113 moved to Laon to attend the lectures of Anselm on Biblical exegesis and Christian doctrine.[6] Unimpressed by Anselm's teaching, Abelard began to offer his own lectures on the book of Ezekiel. Anselm forbade him to continue this teaching, and Abelard returned to Paris where, in around 1115, he became master of the cathedral school of Notre Dame (though the present cathedral was not yet begun) and a canon of Sens (the cathedral of the archdiocese to which Paris belonged).[7]

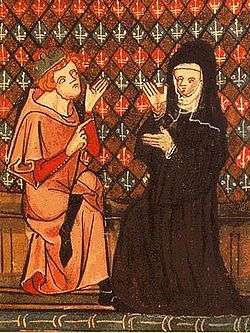

Héloïse

Distinguished in figure and manners, Abelard was seen surrounded by crowds—it is said thousands of students—drawn from all countries by the fame of his teaching. Enriched by the offerings of his pupils, and entertained with universal admiration, he came, as he says, to think himself the only undefeated philosopher in the world. But a change in his fortunes was at hand. In his devotion to science, he had always lived a very regular life, enlivened only by philosophical debate: now, at the height of his fame, he encountered romance.[7]

Héloïse d'Argenteuil lived within the precincts of Notre-Dame, under the care of her uncle, the secular canon Fulbert. She was remarkable for her knowledge of classical letters, which extended beyond Latin to Greek and Hebrew. Abelard sought a place in Fulbert's house and, in 1115 or 1116, began an affair with Héloïse. The affair interfered with his career, and Abelard himself boasted of his conquest. Once Fulbert found out, he separated them, but they continued to meet in secret. Héloïse became pregnant and was sent by Abelard to be looked after by his family in Brittany, where she gave birth to a son whom she named Astrolabe after the scientific instrument.[6][7][lower-alpha 2]

To appease Fulbert, Abelard proposed a secret marriage so as not to mar his career prospects. Héloïse initially opposed it, but the couple were married. When Fulbert publicly disclosed the marriage, and Héloïse denied it, Abelard sent Héloïse to the convent at Argenteuil, where she had been brought up, in order to protect her from her uncle. Héloïse dressed as a nun and shared the nun's life, though she was not veiled.

Fulbert, most probably believing that Abelard wanted to be rid of Héloïse by forcing her to become a nun, arranged for a band of men to break into Abelard's room one night and castrate him. Roscellinus would later belittle Abelard for getting castrated.[11] Later, Abelard decided to become a monk at the monastery of St Denis, near Paris.[6] Before doing so he insisted that Héloïse take vows as a nun. Héloïse sent letters to Abelard, questioning why she must submit to a religious life for which she had no calling.[7]

Later life

In the Abbey of Saint-Denis, the 40-year-old Abelard sought to bury himself as a monk with his woes out of sight.[12] Finding no respite in the cloister, and having gradually turned again to study, he gave in to urgent entreaties, and reopened his school at an unknown priory owned by the monastery. His lectures, now framed in a devotional spirit, and with lectures on theology as well as his previous lectures on logic, were once again heard by crowds of students, and his old influence seemed to have returned. Using his studies of the Bible and — in his view — inconsistent writings of the leaders of the church as his basis, he wrote Sic et Non (Yes and No).[6]

No sooner had he published his theological lectures (the Theologia Summi Boni) than his adversaries picked up on his rationalistic interpretation of the Trinitarian dogma. Two pupils of Anselm of Laon, Alberich of Reims and Lotulf of Lombardy, instigated proceedings against Abelard, charging him with the heresy of Sabellius in a provincial synod held at Soissons in 1121. They obtained through irregular procedures an official condemnation of his teaching, and Abelard was made to burn the Theologia himself. He was then sentenced to perpetual confinement in a monastery other than his own, but it seems to have been agreed in advance that this sentence would be revoked almost immediately, because after a few days in the convent of St. Medard at Soissons, Abelard returned to St. Denis.[8]

Life in his own monastery proved no more congenial than before. For this Abelard himself was partly responsible. He took a sort of malicious pleasure in irritating the monks. As if for the sake of a joke, he cited Bede to prove that the believed founder of the monastery of St Denis, Dionysius the Areopagite had been Bishop of Corinth, while the other monks relied upon the statement of the Abbot Hilduin that he had been Bishop of Athens. When this historical heresy led to the inevitable persecution, Abelard wrote a letter to the Abbot Adam in which he preferred to the authority of Bede that of Eusebius of Caesarea's Historia Ecclesiastica and St. Jerome, according to whom Dionysius, Bishop of Corinth, was distinct from Dionysius the Areopagite, bishop of Athens and founder of the abbey, though, in deference to Bede, he suggested that the Areopagite might also have been bishop of Corinth. Adam accused him of insulting both the monastery and the Kingdom of France (which had Denis as its patron saint); life in the monastery grew intolerable for Abelard, and he was finally allowed to leave.[13]

Abelard initially lodged at St Ayoul of Provins, where the prior was a friend. Then, after the death of Abbot Adam in March 1122, Abelard was able to gain permission from the new abbot, Suger, to live "in whatever solitary place he wished". In a deserted place near Nogent-sur-Seine in Champagne, he built a cabin of stubble and reeds, and a simple oratory dedicated to the Trinity and became a hermit. When his retreat became known, students flocked from Paris, and covered the wilderness around him with their tents and huts. He began to teach again there. The oratory was rebuilt in wood and stone and rededicated as the Oratory of the Paraclete.[13]

Abelard remained at the Paraclete for about five years. His combination of the teaching of secular arts with his profession as a monk was heavily criticized by other men of religion, and Abelard contemplated flight outside Christendom altogether.[14] Abelard therefore decided to leave and find another refuge, accepting sometime between 1126 and 1128 an invitation to preside over the Abbey of Saint-Gildas-de-Rhuys on the far-off shore of Lower Brittany. The region was inhospitable, the domain a prey to outlaws, the house itself savage and disorderly.[13] There, too, his relations with the community deteriorated.[14]

During this time, however, Abelard came back into contact with Héloïse. In April 1129, Abbot Suger of St Denis succeeded in his plans to have the nuns, including Héloïse, expelled from the convent at Argenteuil, in order to take over the property for St Denis. Héloïse had meanwhile become the head of a new foundation of nuns called the Paraclete. Abelard became the abbot of the new community and provided it with a rule and with a justification of the nun's way of life; in this he emphasized the virtue of literary study. He also provided books of hymns he had composed, and in the early 1130s he and Héloïse composed a collection of their own love letters and religious correspondence.[14]

Lack of success at St Gildas made Abelard decide to take up public teaching again (although he remained for a few more years, officially, Abbot of St Gildas). It is not entirely certain what he then did, but given that John of Salisbury heard Abelard lecture on dialectic in 1136, it is presumed that he returned to Paris and resumed teaching on the Montagne Sainte-Geneviève. It is presumed his lectures included logic, at least until 1136,[lower-alpha 3] but were mainly concerned with the Bible, Christian doctrine, and ethics. Then he produced further drafts of his Theologia in which he analyzed the sources of belief in the Trinity and praised the pagan philosophers of classical antiquity for their virtues and for their discovery by the use of reason of many fundamental aspects of Christian revelation.[14]

At some point in this time Abelard wrote, among other things, his famous Historia Calamitatum. This moved Héloïse to write her first Letter;[15] the first being followed by the two other Letters, in which she finally accepted the part of resignation, which, now as a brother to a sister, Abelard commended to her. Sometime before 1140, Abelard published his masterpiece, Ethica or Scito te ipsum (Know Thyself), where he analyzes the idea of sin and that actions are not what a man will be judged for but intentions.[6] During this period, he also wrote Dialogus inter Philosophum, Judaeum et Christianum (Dialogue between a Philosopher, a Jew, and a Christian), and also Expositio in Epistolam ad Romanos, a commentary on St. Paul's epistle to the Romans, where he expands on the meaning of Christ's life.[6]

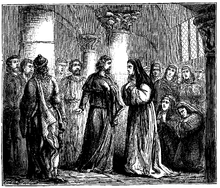

Conflicts with Bernard of Clairvaux

Abelard was to face, however, another challenge which would put a final end to his teaching career. After 1136, it is not clear whether Abelard had stopped teaching, or whether he perhaps continued with all except his lectures on logic until as late as 1141. Whatever the exact timing, a process was instigated by William of St Thierry, who discovered what he considered to be heresies in some of Abelard's teaching. In spring 1140 he wrote to the Bishop of Chartres and to Bernard of Clairvaux denouncing them. Another, less distinguished, theologian, Thomas of Morigny, also produced at the same time a list of Abelard's supposed heresies, perhaps at Bernard's instigation. Bernard's complaint mainly is that Abelard has applied logic where it is not applicable, and that is illogical.[16] Amid pressure from Bernard, Abelard challenged Bernard either to withdraw his accusations, or to make them publicly at the important church council at Sens planned for 2 June 1141. In so doing, Abelard put himself into the position of the wronged party and forced Bernard to defend himself from the accusation of slander. Bernard avoided this trap, however: on the eve of the council, he called a private meeting of the assembled bishops and persuaded them to condemn, one by one, each of the heretical propositions he attributed to Abelard. When Abelard appeared at the council the next day, he was presented with a list of condemned propositions imputed to him.[17]

Refusing to answer to these propositions, Abelard left the assembly, appealed to the Pope, and set off for Rome, hoping that the Pope would be more supportive. However, this hope was unfounded. On 16 July 1141, Pope Innocent II issued a bull excommunicating Abelard and his followers and imposing perpetual silence on him, and in a second document he ordered Abelard to be confined in a monastery and his books to be burned. Abelard was saved from this sentence, however, by Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny. Abelard had stopped there, on his way to Rome, before the papal condemnation had reached France. Peter persuaded Abelard, already old, to give up his journey and stay at the monastery. Peter managed to arrange a reconciliation with Bernard, to have the sentence of excommunication lifted, and to persuade Innocent that it was enough if Abelard remained under the aegis of Cluny. Abelard was treated not as a condemned heretic, but as a revered and wise scholar. He spent his final months at the priory of St. Marcel, near Chalon-sur-Saône, before he died on 21 April 1142.[17] He is said to have uttered the last words "I don't know", before expiring.[18] He died from a combination of fever and a skin disorder, most likely scurvy.[19]

Disputed resting place/lovers' pilgrimage

Abelard was first buried at St. Marcel, but his remains were soon carried off secretly to the Paraclete, and given over to the loving care of Héloïse, who in time came herself to rest beside them in 1163.

The bones of the pair were moved more than once afterwards, but they were preserved even through the vicissitudes of the French Revolution, and now are presumed to lie in the well-known tomb in Père Lachaise Cemetery in eastern Paris.[20] The transfer of their remains there in 1817 is considered to have considerably contributed to the popularity of that cemetery, at the time still far outside the built-up area of Paris. By tradition, lovers or lovelorn singles leave letters at the crypt, in tribute to the couple or in hope of finding true love.

This remains, however, disputed. The Oratory of the Paraclete claims Abelard and Héloïse are buried there and that what exists in Père-Lachaise is merely a monument, or cenotaph. According to Père-Lachaise, the remains of both lovers were transferred from the Oratory in the early 19th century and reburied in the famous crypt on their grounds.[21] Others believe that while Abelard is buried in the tomb at Père-Lachaise, Heloïse's remains are elsewhere.

Philosophy and theology

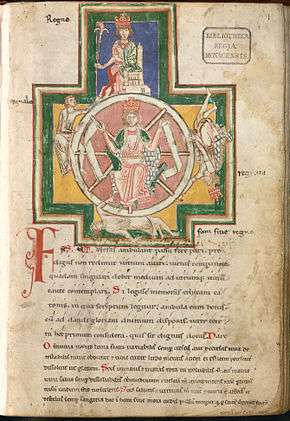

Philosophical thought

The general importance of Abelard lies in his having fixed more decisively than anyone before him the scholastic manner of philosophizing, with the object of giving a formal, rational expression to received ecclesiastical doctrine. Though his particular interpretations may have been condemned, they were conceived in essentially the same spirit as the general scheme of thought afterwards elaborated in the 13th century with approval from the heads of the Church.

He helped to establish the ascendancy of the philosophical authority of Aristotle which became firmly established in the half-century after his death. It was at this time that the completed Organon, and gradually all the other works of the Greek thinker, first came to be available in the schools. Before his time, Plato's authority was the basis for the prevailing Realism. As regards his so-called Conceptualism and his attitude to the question of universals, a discussion can be found in the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Scholasticism.

Outside of his dialectic, it was in ethics that Abelard showed greatest activity of philosophical thought. He stressed the subjective intention as determining, if not the moral character, at least the moral value, of human action. His thought in this direction, anticipating something of modern speculation, is remarkable because his scholastic successors accomplished least in the field of morals, hardly venturing to bring the principles and rules of conduct under pure philosophical discussion, even after they were made fully aware of Aristotle's great ethical inquiries.

Regarding the unbaptized who die in infancy, Abelard—in Commentaria in Epistolam Pauli ad Romanos—emphasized the goodness of God and interpreted St. Augustine of Hippo's "mildest punishment" as the pain of loss at being denied the beatific vision (carentia visionis Dei), without hope of obtaining it, but with no additional punishments. His thought contributed to the forming of Limbo of Infants theory in the 12th–13th centuries.[22]

Philosophical works

- Logica ingredientibus ("Logic for Advanced") completed before 1121

- Petri Abaelardi Glossae in Porphyrium ("The Glosses of Peter Abailard on Porphyry"), c. 1120

- Dialectica, before 1125 (1115–1116 according to John Marenbon, The Philosophy of Peter Abelard, Cambridge University Press 1997).[23]

- Logica nostrorum petitioni sociorum ("Logic in response to the request of our comrades"), c. 1124–1125

- Tractatus de intellectibus ("A treatise on understanding"), written before 1128.[24]

- Sic et Non ("Yes and No") (A list of quotations from Christian authorities on philosophical and theological questions)[25]

- Theologia 'Summi Boni',[26] Theologia christiana,[27] and Theologia 'scholarium'.[26] His main work on systematic theology, written between 1120 and 1140, and which appeared in a number of versions under a number of titles (shown in chronological order)

- Dialogus inter philosophum, Judaeum, et Christianum, (Dialogue of a Philosopher with a Jew and a Christian) 1136–1139.[28]

- Ethica or Scito Te Ipsum ("Ethics" or "Know Yourself"), before 1140.[29]

Later influence

Abelard was an enormous influence on his contemporaries and the course of medieval philosophical thought, but he has been known in modern times mainly for his connection with Héloïse. Only one of his strictly philosophical works, the ethical treatise Scito te ipsum, had been published before the 19th century, in 1721. It was only with the publication by Cousin in 1836 of the collection entitled Ouvrages inedits d'Abelard that Abelard's philosophical work began to be studied more closely. Cousin's collection gave extracts from the theological work Sic et Non ("Yes and No") which is an assemblage of what Abelard saw as opposite opinions on doctrinal points culled from the Fathers as a basis for discussion. The collection also includes the Dialectica, and commentaries on logical works of Aristotle, Porphyry and Boethius. Two works published by Cousin and believed at the time to be by Abelard, the fragment De Generibus et Speciebus (published in the 1836 collection), and also the psychological treatise De Intellectibus (published separately by Cousin in Fragmens Philosophiques, vol. ii.), are now believed on upon internal evidence not to be by Abelard himself, but only to have sprung out of his school. A genuine work, the Glossulae super Porphyrium, from which Charles de Rémusat gave extracts in his monograph Abelard (1845), was published in 1930. The fascinating hypothesis of Abaelard's influence on Menasseh Ben Israel and Spinoza has been developed by Robert Menasse and first published in his essay "Enlightenment as Harmonious Strategy" edited by Versopolis in 2018.[30]

Notes from Pope Benedict XVI

During his general audience on 4 November 2009, Pope Benedict XVI talked about Saint Bernard of Clairvaux and Peter Abelard to illustrate differences in the monastic and scholastic approaches to theology in the 12th century. The Pope recalled that theology is the search for a rational understanding (if possible) of the mysteries of Christian revelation, which is believed through faith — faith that seeks intelligibility (fides quaerens intellectum). But St. Bernard, a representative of monastic theology, emphasized "faith" whereas Abelard, who is a scholastic, stressed "understanding through reason".[31]

For Bernard, faith is based on the testimony of Scripture and on the teaching of the Fathers of the Church. Thus, Bernard found it difficult to agree with Abelard and, in a more general way, with those who would subject the truths of faith to the critical examination of reason — an examination which, in his opinion, posed a grave danger: intellectualism, the relativizing of truth, and the questioning of the truths of faith themselves. Theology for Bernard could be nourished only in contemplative prayer, by the affective union of the heart and mind with God, with only one purpose: to promote the living, intimate experience of God; an aid to loving God ever more and ever better.[31]

According to Pope Benedict XVI, an excessive use of philosophy rendered Abelard's doctrine of the Trinity dangerously fragile and, thus, his idea of God. In the field of morals, his teaching was vague, as he insisted on considering the intention of the subject as the only basis for describing the goodness or evil of moral acts, thereby ignoring the objective meaning and moral value of the acts, resulting in a dangerous subjectivism. But the Pope recognized the great achievements of Abelard, who made a decisive contribution to the development of scholastic theology, which eventually expressed itself in a more mature and fruitful way during the following century. And some of Abelard's insights should not be underestimated, for example, his affirmation that non-Christian religious traditions already contain some form of preparation for welcoming Christ.[31]

Pope Benedict XVI concluded that Bernard's "theology of the heart" and Abelard's "theology of reason" represent the importance of healthy theological discussion and humble obedience to the authority of the Church, especially when the questions being debated have not been defined by the magisterium. St. Bernard, and even Abelard himself, always recognized without any hesitation the authority of the magisterium. Abelard showed humility in acknowledging his errors, and Bernard exercised great benevolence. The Pope emphasized, in the field of theology, there should be a balance between architectonic principles, which are given through Revelation and which always maintain their primary importance, and the interpretative principles proposed by philosophy (that is, by reason), which have an important function, but only as a tool. When the balance breaks down, theological reflection runs the risk of becoming marred by error; it is then up to the magisterium to exercise the needed service to truth, for which it is responsible.[31]

The letters of Abelard and Héloïse

The story of Abelard and Héloïse has proved immensely popular in modern European culture. This story is known almost entirely from a few sources: first, the Historia Calamitatum; secondly, the seven letters between Abelard and Héloïse which survive (three written by Abelard, and four by Héloïse), and always follow the Historia Calamitatum in the manuscript tradition; thirdly, four letters between Peter the Venerable and Héloïse (three by Peter, one by Héloïse).[32] They are, in modern times, the best known and most widely translated parts of Abelard's work.

It is unclear quite how the letters of Abelard and Héloïse came to be preserved. There are brief and factual references to their relationship by 12th-century writers including William Godel and Walter Map. It seems unlikely, however, that the letters were widely known in this period. Rather, the earliest manuscripts of the letters are dated to the late 13th century. It therefore seems likely that the letters sent between Abelard and Héloïse were kept by Héloïse at the Paraclete along with the 'Letters of Direction', and that more than a century after her death they were brought to Paris and copied.[33] At this time, the story of their love affair was summarised by Jean de Meun in his continuation to Le Roman de la Rose.

Their story does not appear to have been widely known in the later Middle Ages, either. There is no mention of the couple in Dante; Chaucer makes a very brief reference in the Wife of Bath's Prologue (lines 677–8), but no more. One of the first people to show a deeper interest in the couple appears to have been Petrarch, who owned an early 14th-century manuscript of the couple's letters. This silence on what is today seen as a particularly touching story is perhaps surprising, given the Renaissance ideal of courtly love – but it is possible that the story of Abelard and Héloïse could not be appropriately fitted into the ideals of the lover's devotion to the chaste and unattainable lady.[34]

The first publication of the letters, in Latin, was in Paris in 1616, simultaneously in two editions. These editions gave rise to numerous translations of the letters into European languages – and consequent 18th- and 19th-century interest in the story of the medieval lovers.[35] In the 18th century, the couple were revered as tragic lovers, who endured adversity in life but were united in death. With this reputation, they were the only individuals from the pre-Revolutionary period whose remains were given a place of honour at the newly founded cemetery of Père Lachaise in Paris. At this time, they were effectively revered as romantic saints; for some, they were forerunners of modernity, at odds with the ecclesiastical and monastic structures of their day and to be celebrated more for rejecting the traditions of the past than for any particular intellectual achievement.[36]

The Historia was first published in 1841 by John Caspar Orelli of Turici. Then, in 1849, Victor Cousin published Petri Abaelardi opera, in part based on the two Paris editions of 1616 but also based on the reading of four manuscripts; this became the standard edition of the letters.[37] Soon after, in 1855, Migne printed an expanded version of the 1616 edition under the title Opera Petri Abaelardi, without the name of Héloïse on the title page.

Critical editions of the Historia Calamitatum and the letters were subsequently published in the 1950s and 1960s.

At various times in the past two hundred years, it has been suggested that not all the letters are genuine. Questions were first raised in 1806 by Ignaz Fessler, and were renewed by J. C. Orelli in 1844 and Ludovic Lalanne in 1855, who all suggested that the letters might simply be a literary fiction. Doubts were raised at intervals in the succeeding decades. More recently, John Benton hypothesised (in 1972) that the entire letter collection might have been forged in the late 13th century, or by Abelard himself (a position Benton had reverted to by 1979). In the aftermath of reaction to Benton's thought, though, scholars have become more confident in asserting the genuine nature of the letters.[38]

According to historian Constant Mews, The Lost Love Letters of Héloïse and Abelard, 113 anonymous love letters found in a 15th-century manuscript represent the correspondence exchanged by Héloïse and Abelard during the earlier phase of their affair.[39] These are not to be confused with the accepted Letters of Abelard and Héloïse which were written nearly fifteen years after their romance ended.[40]

Music

Abelard was also long known as an important poet and composer. He composed some celebrated love songs for Héloïse that are now lost, and which have not been identified in the anonymous repertoire. Héloïse praised these songs in a letter: "The great charm and sweetness in language and music, and a soft attractiveness of the melody obliged even the unlettered".[41]

Abelard composed a hymnbook for the religious community that Héloïse joined. This hymnbook, written after 1130, differed from contemporary hymnals, such as that of Bernard of Clairvaux, in that Abelard used completely new and homogeneous material. The songs were grouped by metre, which meant that it was possible to use comparatively few melodies. Only one melody from this hymnal survives, O quanta qualia.[41]

Abelard also wrote six biblical planctus (laments):

- Planctus Dinae filiae Iacob; inc.: Abrahae proles Israel nata (Planctus I)

- Planctus Iacob super filios suos; inc.: Infelices filii, patri nati misero (Planctus II)

- Planctus virginum Israel super filia Jepte Galadite; inc.: Ad festas choreas celibes (Planctus III)

- Planctus Israel super Samson; inc.: Abissus vere multa (Planctus IV)

- Planctus David super Abner, filio Neronis, quem Ioab occidit; inc.: Abner fidelissime (Planctus V)

- Planctus David super Saul et Jonatha; inc.: Dolorum solatium (Planctus VI).

In surviving manuscripts these pieces have been notated in diastematic neumes which resist reliable transcription. Only Planctus VI was fixed in square notation. Planctus as genre influenced the subsequent development of the lai, a song form that flourished in northern Europe in the 13th and 14th centuries.

Melodies that have survived have been praised as "flexible, expressive melodies [that] show an elegance and technical adroitness that are very similar to the qualities that have been long admired in Abelard's poetry."[42]

Cultural references

- François Villon mentions Héloïse and Abelard in his most famous poem "Ballade des dames du temps jadis".

- The subtitle of Julie, or the New Heloise (1761), an epistolary novel by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, alludes to the history of Héloïse and Abelard.

- Helen Waddell's novel Peter Abelard (1933) is loosely based on Abelard and Héloïse. The novel was the basis of the play Abelard and Héloïse (1970) by Ronald Millar.

- Alexander Pope's poem Eloisa to Abelard (1717) is written from the point of view of Héloïse in her convent.

- Abelard and Héloïse are referenced throughout Robertson Davies's novel The Rebel Angels.

- Henry Miller uses Abelard's "Foreword to Historia Calamitatum" as the motto of Tropic of Capricorn (1938).

- Stealing Heaven (1988) starring Derek de Lint and Kim Thomson is a based on Marion Meade's 1979 novel about the couple.

- Mark Twain's The Innocents Abroad tells a satirical version of the lovers' story.

- Henry Adams devotes a chapter to Abelard's life in Mont Saint Michel and Chartres

- In Charles Williams' 1931 novel The Place of the Lion, one of the main characters, Damaris, is extremely focused on her research concerning Abelard, which is used as a counterpoint to many of the theological and transcendental issues present in the book.

- George Moore's 1921 novel, Héloïse and Abélard, recounts their relationship from first meeting through final separation.[43]

- Anne Carson's 2005 collection Decreation includes a screenplay about Abelard and Héloïse.

- Howard Brenton's play In Extremis: The Story Of Abelard & Heloise was premiered at Shakespeare's Globe in 2006.[44]

- In the film Being John Malkovich, John Cusack's character, performs puppet show of Abelard & Heloise on a street corner, which gets him beaten up by an irate father, due to its sexual suggestiveness.

- In the HBO series The Sopranos, the character Carmela Soprano finds the letters of "Abelard and Heloise" in the bathroom of her extramarital lover, various parallels are drawn through the 5th season.

- Rick Riordan's book The Trials of Apollo: The Dark Prophecy contains a pair of gryphons named "Heloise and Abelard".

- James Carroll's 2017 novel The Cloister retells the story of Abelard and Héloïse, interweaving it with the friendship of a Catholic priest and a French Jewish woman in the post-Holocaust twentieth century.

Notes

- Older accounts of the meeting suggest that this resulted in a long duel that ended in the downfall of the philosophic theory of Realism, till then dominant in the early Middle Ages (to be replaced by Abelard's Conceptualism, or by Nominalism, the principal rival of Realism prior to Abelard).

- Astrolabe, the son of Abelard and Héloïse, is mentioned by Peter the Venerable of Cluny, where Abelard spent his last years, when Peter the Venerable wrote to Héloise: "I will gladly do my best to obtain a prebend in one of the great churches for your Astrolabe, who is also ours for your sake". A 'Petrus Astralabius' is recorded at the Cathedral of Nantes in 1150, and the same name appears at the Cistercian abbey at Hauterive in what is now Switzerland, but it is uncertain whether this is the same man. However, Astrolabe is recorded as dying at Paraclete on 29 or 30 October, year unknown, appearing in the necrology as "Petrus Astralabius magistri nostri Petri filius". (See Radice 1947, (trans.), The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1974), p. 287; for the necrology, see Enid McLeod, Héloise (London: Chatto & Windus, 2nd edn., 1971, pp. 253, 283-84)).

- Given John of Salisbury's testimony.

References

- Weaver, J. Denny (2001), The Nonviolent Atonement, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

- Beilby, James K.; Eddy, Paul R. (2009), The Nature of the Atonement: Four Views, InterVarsity Press

- Guilfoy, Kevin, "John of Salisbury", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2015 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

- Peter King, Andrew Arlig (2018). "Peter Abelard". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University. Retrieved 10 October 2019. This source has a detailed description of his philosophical work.

- Chambers Biographical Dictionary, ISBN 0-550-18022-2, p. 3; Marenbon 2004, p. 14.

- Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "Abelard, Peter". Encyclopædia Britannica. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, IL: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- Abelard, Peter. Historia Calamitatum. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- Marenbon 2004, p. 15.

- Edward Cletus Sellner (2008). Finding the Monk Within: Great Monastic Values for Today. Paulist Press. pp. 238–. ISBN 978-1-58768-048-9.

- Robertson & Shotwell 1911, p. 40.

- Russell, Bertrand. The History of Western Philosophy. Simon & Schuster, 1945, p. 436.

- Kevin Guilfoy, Jeffrey E. Brower (2004). The Cambridge Companion To Abelard. Abelard and monastic reform: Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-521-77596-0.

- Robertson & Shotwell 1911, p. 41.

- David Edward Luscombe. "Peter Abelard". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on 2015-05-02.

- Wheeler, Bonnie (2000). Listening to Héloïse: the voice of a twelfth-century woman. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0-312-21354-1.

- John R. Sommerfeldt (2004). Bernard of Clairvaux on the Life of the Mind. Paulist Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8091-4203-3.

- Marenbon 2004, p. 17.

- Davies, Norman (1996). Europe: A history. Oxford University Press. p. 687. ISBN 978-0-19-820171-7. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- Donaldson, Norman and Betty (1980). How Did They Die?. Greenwich House. ISBN 978-0-517-40302-0.

- Burge 2006, p. 276.

- Burge 2006, pp. 276–277.

- International Theological Commission, the Vatican. "The Hope of Salvation for Infants Who Die Without Being Baptised". Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- Latin text in L. M. De Rijk, ed, Petrus Abaelardus: Dialectica, 2nd edn, (Assen: Van Gorcum, 1970)

- English translation in Peter King, Peter Abailard and the Problem of Universals in the Twelfth Century, (Princeton, 1982)

- The Latin text is printed in Blanche Boyer and Richard McKeon, eds, Peter Abailard: Sic et Non. A Critical Edition, (University of Chicago Press 1977).

- Latin text in Eligius M. Buytaert and Constant Mewsin Petri, eds, Abaelardi opera theologica. CCCM13, (Brepols: Turnholt, 1987).

- Latin text in Eligius M. Buytaert, ed, Petri Abaelardi opera theologica. CCCM12, (Brepols: Turnholt 1969). Substantial portions are translated into English in James Ramsay McCallum, Abelard's Christian Theology, (Oxford: Blackwell, 1948).

- English translations in Pierre Payer, Peter Abelard: A Dialogue of a Philosopher with aJew and a Christian, (Toronto: The Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies Publications, 1979), and Paul Spade, Peter Abelard: Ethical Writings, (Indianapolis: HackettPublishing Company, 1995).

- English translations in David Luscombe, Ethics, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), and in Paul Spade, Peter Abelard: Ethical Writings, (Indianapolis: HackettPublishing Company, 1995).

- Menasse, Robert (22 March 2018). "Enlightenment as a Harmonious Strategy". Versopolis. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- "St. Bernard and Peter Abelard". National Catholic Register – EWTN News, Inc. November 13, 2009. Archived from the original on June 19, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- In the Latin categorising of Abelard's work, these are numbered Epistolae 2-8, because the Historia calamitatum (which takes the form of a letter) is termed Epistolae 1.

- Radice 1947, p. 47.

- Radice 1947, p. 48.

- Radice 1947, p. 49.

- Constant J Mews, Abelard and Héloïse, (Oxford: OUP, 2005), p4

- Radice 1947, p. 50.

- Constant J. Mews, Abelard and Héloïse, (Oxford: OUP, 2005), p16

- Mews, Constant (2001). The Lost Love Letters of Héloïse and Abelard: Perceptions of Dialogue in Twelfth-Century France. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-23941-1.

- Marenbon, John (2010). Robert E. Bjork (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-866262-4.

- Weinrich, Lorenz (2001). "Peter Abelard". In Root, Deane L. (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Oxford University Press.

- Oliver, Michael (1995). "Review: a CD of Abelard's music". Gramophone. Archived from the original on December 9, 2007. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

- George Moore (1921) Héloïse and Abélard, Boni and Liveright, New York OCLC 174975329

- "Press Release Comedy July 2006" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 7 December 2008.

Attribution:

Sources

- Burge, James (2006). Héloïse & Abelard: A New Biography. HarperOne. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-0-06-081613-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marenbon, John (2004). "Life, milieu and intellectual contexts". In Brower, Jeffrey E; Guilfoy, Kevin (eds.). 'The Cambridge Companion to Abelard. Cambridge University Press. pp. 14–17.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Introduction". The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse. Translated by Radice, Betty. Introduction by Betty C. Penguin. 1947. pp. 47–50.CS1 maint: others (link)

Further reading

- Thomas J. Bell, Peter Abelard after Marriage. The Spiritual Direction of Héloïse and Her Nuns through Liturgical Song, Cistercian Studies Series 21, (Kalamazoo, Michigan, Cistercian Publications. 2007).

- Brower, Jeffrey; Kevin Guilfoy (2004). The Cambridge Companion to Abelard. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77247-1.

- Clanchy, M. (1997). Abelard: A Medieval Life. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-21444-1.

- Gilson, Étienne (1960). Héloïse and Abelard. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06038-2.

- Marenbon, John (1997). The Philosophy of Peter Abelard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-66399-1.

- Mews, Constant (2005). Abelard and Héloïse. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515689-8.

- Sapir Abulafia, Anna (1995). Christians and Jews in the Twelfth-Century Renaissance. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-00012-3.

Modern editions and translations of Abelard's works

- "Logica Ingredientibus, Commentary of Porphyry's Isagoge". Five Texts on the Medieval Problem of Universals: Porphyry, Boethius, Abelard, Duns Scotus, Ockham. Translated by Spade, P.V. Indianapolis: Hackett. 1994.

- Abelard & Héloïse: The Letters and other Writings. Translated by Levitan, William (introduction and notes by William Levitan ed.). 2007. ISBN 978-0-87220-875-9.

- Radice, Betty (1974). The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-044297-7.

- Planctus. Consolatoria, Confessio fidei, by M. Sannelli, La Finestra editrice, Lavis 2013, ISBN 978-8895925-47-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter Abelard. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Peter Abelard |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Peter Abelard |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Peter Abelard. |

- King, Peter. "Peter Abelard". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Guilfoy, Kevin. "Peter Abelard". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Abelard: Logic, Semantics, Ontology and His Theories of the Copula

- Abelard and Héloïse from In Our Time

- Peter King's biography of Abelard in The Dictionary of Literary Biography

- The Love Letters of Abelard and Héloïse. Trans. by Anonymous (1901).

- Works by Peter Abelard at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Peter Abelard at Internet Archive

- Works by Peter Abelard at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)