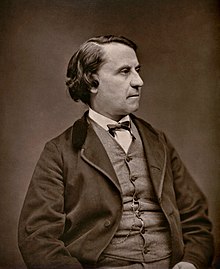

Louis Blanc

Louis Jean Joseph Charles Blanc (/blɑːn/; French: [blɑ̃]; 29 October 1811 – 6 December 1882) was a French politician and historian. A socialist who favored reforms, he called for the creation of cooperatives in order to guarantee employment for the urban poor. Although Blanc's ideas of the workers' cooperatives were never realized, his political and social ideas greatly contributed to the development of socialism in France.

Louis Blanc | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 29 October 1811 Madrid, Kingdom of Spain |

| Died | 6 December 1882 (aged 71) |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Socialism |

Main interests | Politics, history, economy |

Notable ideas | Right to work, national Workshops |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

Following the Revolution of 1848, Blanc became a member of the provisional government and began advocating for cooperatives which would be initially aided by the government but ultimately controlled by the workers themselves. Blanc's advocacy failed and, caught between radical worker tendencies and the National Guard, he was forced into exile. Blanc returned to France in 1870, shortly before the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian war and served as a member of the National Assembly. While he did not support the Paris Commune, Blanc successfully proposed amnesty to the Communards.

Biography

Early years

Blanc was born in Madrid. His father held the post of inspector-general of finance under Joseph Bonaparte. His younger brother was Charles Blanc, who later became an influential art critic.[2] Failing to receive aid from Pozzo di Borgo, his mother's uncle, Louis Blanc studied law in Paris, living in poverty, and became a contributor to various journals. In the Revue du progres, which he founded, he published in 1839 his study on L'Organisation du travail. The principles laid down in this famous essay form the key to Louis Blanc's whole political career. He attributes all the evils that afflict society to the pressure of competition, whereby the weaker are driven to the wall. He demanded the equalization of wages, and the merging of personal interests in the common good—"De chacun selon ses facultés, à chacun selon ses besoins",[3] which is often translated as "from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs." This was to be affected by the establishment of "social workshops", a sort of combined co-operative society and trade-union, where the workmen in each trade were to unite their efforts for their common benefit. In 1841 he published his Histoire de dix ans 1830-1840, an attack upon the monarchy of July. It ran through four editions in four years.

Revolution of 1848

In 1847, Blanc published the two first volumes of his Histoire de la Revolution Française. Its publication was interrupted by the Revolution of 1848, when he became a member of the provisional government. It was on his motion that, on 25 February, the government undertook "to guarantee the existence of the workmen by work"; and though his demand for the establishment of a ministry of labour was refused—as beyond the competence of a provisional government—he was appointed to preside over the government labour commission (Commission du Gouvernement pour les travailleurs) established at the Palais du Luxembourg to inquire into and report on the labour question.

The revolution of 1848 was the real chance for Louis Blanc's ideas to be implemented. His theory of using the established government to enact change was different from those of other socialist theorists of his time. Blanc believed that workers could control their own livelihoods, but knew that unless they were given help to get started the cooperative workshops would never work. To assist this process along Blanc lobbied for national funding of these workshops until the workers could assume control. To fund this ambitious project, Blanc saw a ready revenue source in the rail system. Under government control the railway system would provide the bulk of the funding needed for this and other projects Blanc saw in the future.

When the workshop program was ratified in the National Assembly, Blanc's chief rival Émile Thomas was put in control of the project. The National Assembly was not ready for this type of social program and treated the workshops as a method of buying time until the assembly could gather enough support to stabilize themselves against another worker rebellion. Thomas's deliberate failure in organizing the workshops into a success only seemed to anger the public more. The people had been promised a job and a working environment in which the workers were in charge, from these government funded programs. What they had received was hand outs and government funded work parties to dig ditches and hard manual labor for meager wages or paid to remain idle. When the workshops were closed the workers rebelled again but were put down by force by the National Guard. The National Assembly was also able to blame Blanc for the failure of the workshops. His ideas were questioned and he lost much of the respect which had given him influence with the public.

Between the sans-culottes, who tried to force him to place himself at their head, and the National Guards, who mistreated him, he was nearly killed. Rescued with difficulty, he escaped with a false passport to Belgium, and then to London. He was condemned to deportation in absentia by a special tribunal at Bourges. Against trial and sentence he alike protested, developing his protest in a series of articles in the Nouveau Monde, a review published in Paris under his direction. These he afterwards collected and published as Pages de l'histoire de la révolution de 1848 (Brussels, 1850).

Exile

During his stay in Britain he made use of the unique collection of materials for the revolutionary period preserved at the British Museum to complete his Histoire de la Revolution Française 12 vols. (1847–1862). In 1858 he published a reply to Lord Normanby's A Year of Revolution in Paris (1858), which he developed later into his Histoire de la révolution de 1848 (2 vols., 1870–1880). He was also active in the masonic organisation, the Conseil Suprême de l'Ordre Maçonnique de Memphis. His membership in the London-based La Grand Loge des Philadelphes is unconfirmed.

Return to France

As far back as 1839, Louis Blanc had vehemently opposed the idea of a Napoleonic restoration, predicting that it would be "despotism without glory", "the Empire without the Emperor." He therefore remained in exile until the fall of the Second Empire in September 1870, after which he returned to Paris and served as a private in the National Guard. On 8 February 1871 he was elected a member of the National Assembly, in which he maintained that the Republic was "the necessary form of national sovereignty", and voted for the continuation of the war; yet, though a leftist, he did not sympathize with the Paris Commune, and exerted his influence in vain on the side of moderation. In 1878 he advocated the abolition of the presidency and the Senate. In January 1879 he introduced into the chamber a proposal for the amnesty of the Communards, which was carried. This was his last important act. His declining years were darkened by ill-health and by the death, in 1876, of his wife Christina Groh, whom he had married in 1865. He died at Cannes, and on 12 December received a state funeral in Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Legacy

Blanc possessed a picturesque and vivid style, and considerable power of research; but the fervour with which he expressed his convictions, while placing him in the first rank of orators, tended to turn his historical writings into political pamphlets. His political and social ideas have had a great influence on the development of socialism in France. His Discours politiques (1847–1881) was published in 1882. his most important works, besides those already mentioned, are Lettres sur l'Angleterre (1866–1867), Dix années de l'Histoire de l'Angleterre (1879–1881), and Questions d'aujourd'hui et de demain (1873–1884).

The Paris Metro Station Louis Blanc is named after him.

Capitalism

Blanc is sometime cited as the first person to use the word capitalism in something like its modern form. While he did not mean the economic system described by Karl Marx in Das Kapital, Blanc sowed the seeds of that usage, coining the word to mean the holding of capital away from others:

What I call 'capitalism' that is to say the appropriation of capital by some to the exclusion of others.[4]

— Organisation du Travail (1851)

Thought

Reformist socialism

Blanc was unusual in advocating for socialism without revolution first.[5]

Right to work

Blanc invented the right to work with his Le Droit au Travail.[6]

Religion

Blanc resisted what he perceived as the atheism implicit in Hegel, claiming that it corresponded to anarchism in politics and was not an adequate basis for democracy.[7] Engels claimed that "Parisiann reformers of the Louis Blanc trend" could only imagine atheists as monsters.[8]

Instead, Blanc claimed that religion was foundational for revolution to take place, in keeping with the romantic tradition.[9] He regarded liberalism and Protestantism as part of the same historical and ideological movement[10] and accordingly considered the French Revolution of 1789 as a political outgrowth of the individualistic rejection of authority inherent in Protestantism and heretical movements.[11][12] Blanc thought the best of the revolution was the Jacobin dictatorship in the communitarian spirit of Catholicism.[13] Blanc himself sought to combine Catholicism and Protestantism in order to synthesize the values of authority, community, and individualism that he both affirmed as necessary for community.[11] He was unusual in combining Catholicism and socialism.[14]

Along with Etienne Cabet, Blanc advocated for what he understood as true Christianity while simultaneously critiquing the religion of Catholic clergy.[9] He was hopeful about the religious innovation taking place in early revolutionary france.[14] His understanding of God was shaped by romanticism and was similar to Rousseau, Phillipe Buchez and Respail.[15]

Works

In 1834, he moved to Paris and soon began working there at the newspaper "Common Sense."

See also

References

- Finn, Margot C. (2003). After Chartism: Class and Nation in English Radical Politics 1848-1874. Cambridge University Press. p. 176.

- Varouxakis, Georgios (2004). "Blanc, (Jean Joseph) Louis (1811–1882), political thinker and exile". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- Louis Blanc, Plus de Girondins, 1851, p. 92.

- Conceptualizing Capitalism: Institutions, Evolution, Future

- Herzog et al. 1884, p. 2205.

- Day 1914, p. 85.

- Moggach 2011, p. 319.

- Marx & al 2001, p. 63.

- Joskowicz 2013, p. 46.

- Stirner, Byington & Martin 2012, p. 106.

- Furet & Ozouf 1989, p. 902.

- Malia & Emmons 2006, p. 59.

- Comay 2011, p. 187.

- Furet & Ozouf 1989, p. 700.

- Eisenstein 1959, p. 136.

- Leo A. Loubère, (1961) Louis Blanc: His Life and His Contribution to the Rise of French Jacobin-Socialism

Sources

- G.D.H Cole, Socialist Thought, The Forerunners 1789-1850 (1959)

- Comay, R. (2011). Mourning Sickness: Hegel and the French Revolution. Cultural Memory in the Present. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6127-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Day, H.C. (1914). Catholic Democracy: Individualism and Socialism. Longmans, Green, and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eisenstein, E.L. (1959). The first professional revolutionist. Harvard historical monographs. Harvard University Press. p. 136.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Furet, F.; Ozouf, M. (1989). A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-17728-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Furet, F.; Ozouf, M. (1989). A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-17728-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Furet, F.; Ozouf, M. (1989). A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-17728-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herzog, J.J.; Schaff, P.; Jackson, S.M.; Schaff, D.S. (1884). "Socialism". A Religious Encyclopædia, Or, Dictionary of Biblical, Historical, Doctrinal and Practical Theology: Based on the Real-encyklopädie of H Erzog, Plitt and Hauck. T. & T. Clark.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Joskowicz, A. (2013). The Modernity of Others: Jewish Anti-Catholicism in Germany and France. Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-8840-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marx, K.; al, K.M. (2001). Marxism, Socialism and Religion. Resistance Marxist library. Resistance Books. ISBN 978-1-876646-01-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harry W. Laidler, A History of Socialist Thought (1927)

- Malia, M.E.; Emmons, T. (2006). History's Locomotives: Revolutions and the Making of the Modern World. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-13528-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moggach, D. (2011). Politics, Religion, and Art: Hegelian Debates. Book collections on Project MUSE. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 978-0-8101-2729-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stirner, M.; Byington, S.T.; Martin, J.J. (2012) [1982]. The Ego and His Own: The Case of the Individual Against Authority. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-12276-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- G.R.S. Taylor, Leaders of Socialism (1968)

- Attribution

- L. Fiaux, Louis Blanc (1883)

Further reading

- Hazareesingh, S. (2015). How the French Think: An Affectionate Portrait of an Intellectual People. Basic Books. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-465-06166-2.

- Day, H.C. (1914). Catholic Democracy: Individualism and Socialism. Longmans, Green, and Company.

External links

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.