Cilice

A cilice /ˈsɪlɪs/, also known as a sackcloth,[1] was originally a garment or undergarment made of coarse cloth or animal hair (a hairshirt) worn close to the skin. It is used by members of various Christian traditions (including some communicants of the Catholic,[2] Anglican,[3] Lutheran,[4] Methodist,[5] and Scottish Presbyterian Churches[6]) as a self-imposed means of repentance and mortification of the flesh; it is often worn during the Christian penitential season of Lent, especially on Ash Wednesday, Good Friday, and other Fridays of the Lenten season.[7]

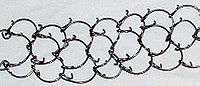

Cilices were originally made from sackcloth or coarse animal hair so they would irritate the skin. Other features were added to make cilices more uncomfortable, such as thin wires or twigs. In modern religious circles, cilices are simply any device worn for the same purposes.

Etymology

The word cilice derives from the Latin cilicium, a covering made of goat's hair from Cilicia, a Roman province in south-east Asia Minor.[8] The reputed first Scriptural use of this exact term is in the Vulgate (Latin) translation of Psalm 35:13, "Ego autem, cum mihi molesti essent, induebar cilicio." ("But as for me, when they were sick, my clothing was sackcloth" in the King James Bible). The term is translated as hair-cloth in the Douay–Rheims Bible, and as sackcloth in the King James Bible and Book of Common Prayer. Sackcloth can also mean burlap, but is often mentioned as a symbol of mourning and was probably a form of hairshirt.

Use

There is some evidence, based on analyses of both clothing represented in art and preserved skin imprint patterns at Çatalhöyük in Turkey, that the usage of the cilice predates written history. This finding has been mirrored at Göbekli Tepe, another Anatolian site, indicating the widespread manufacturing of cilices. Ian Hodder has argued that "self-injuring clothing was an essential component of the Catalhöyük culturo-ritual entanglement, representing 'cleansing' and 'lightness'."[9]

In Biblical times, it was the Jewish custom to wear a hairshirt (sackcloth) when mourning (Genesis 37:34, 2 Samuel 3:31, Esther 4:1), but not in order to cause harm to oneself, which is forbidden in the Jewish religion. In the New Testament, John the Baptist wore "a garment of camel’s hair" (Matthew 3:4). Historically, some Christian denominations have worn sackcloth to mortify the flesh or as penance for adorning oneself.

Cilices have been used for centuries in the Catholic Church as a mild form of bodily penance akin to fasting. Thomas Becket was wearing a hairshirt when he was martyred,[10] St. Patrick reputedly wore a cilice, Charlemagne was buried in a hairshirt, and Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Germany, famously wore one in the Walk to Canossa during the Investiture Controversy. Prince Henry the Navigator was found to be wearing a hairshirt at the time of his death in 1460. St. Francis of Assisi, St. Ignatius Loyola and St. Therese of Lisieux are known to have used them. Scottish king James IV wore a cilice during Lent to repent of the indirect role he played in his father's death. In modern times they have been used by Mother Teresa, St. Padre Pio, and Pope Paul VI.[11] In the Discalced Carmelite convent of St. Teresa in Livorno, Italy, members of Opus Dei who are celibate (about 30% of the membership), and the Franciscan Brothers and Sisters of the Immaculate Conception continue an ascetic use of the cilice.[12] According to John Allen, an American Catholic writer, its practice in the Catholic Church is "more widespread than many observers imagine".[13]

Some high church Anglicans, including Edward Bouverie Pusey, wore hairshirts as a part of their spirituality.[3]

In the Presbyterian Church of Scotland, influenced by the evangelical revival, penitents were dressed in sackcloth and called in front of the chancel, where they were asked to admit their sins.[6]

In some Methodist churches, on Ash Wednesday, communicants, along with receiving ashes, also receive a piece of sackcloth "as a reminder of our own sinful ways and need for repentance".[14]

In popular culture

In Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code, one of the antagonists, an albino numerary named Silas associated with the religious organization Opus Dei, wears a cilice in the form of a spiked belt around his thigh. The sensationalized depiction in the novel has been criticized for its inaccuracy in subsequent books and by Opus Dei itself, which issued a press release responding to the movie's depiction of the practice, claiming "In reality, they cause a fairly low level of discomfort comparable to fasting. There is no blood, no injury, nothing to harm a person's health, nothing traumatic. If it caused any harm, the Church would not allow it."[11][15]

See also

References

- Jeffrey, David L. (1992). A Dictionary of Biblical Tradition in English Literature. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 673. ISBN 9780802836342.

- Stravinskas, Peter M. J.; Shaw, Russell B. (1998). Our Sunday Visitor's Catholic Encyclopedia. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing. p. 483. ISBN 9780879736699.

- Knight, Mark; Mason, Emma (16 November 2006). Nineteenth-Century Religion and Literature: An Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 9780191535017.

Pusey regularly endured a hair shirt as well as self- imposed flagellation and fasting routines.

- Neve, Juergen Ludwig (1914). The Augsburg Confession: A Brief Review of Its History and an Interpretation of Its Doctrinal Articles, with Introductory Discussions on Confessional Questions. Lutheran Publication Society. p. 150.

- Bergen, Jeremy M. (31 March 2011). Ecclesial Repentance: The Churches Confront Their Sinful Pasts. A&C Black. p. 255. ISBN 9780567523686.

In fact, it was scandal of disunity within Methodism that led UMC leaders to address the issue of racism as the underlying cause. ... The petition for forgiveness proceeded on two distinct but interrelated levels. Each of the approximately 3,000 persons in the assemble was called to silent personal confession of the sin of racism before God, publicly symbolized by receiving ... sackcloth ... and the imposition of ashes.

- Yates, Nigel (11 June 2014). Eighteenth Century Britain: Religion and Politics 1714-1815. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 9781317866480.

The Evangelical revival in Scotland encouraged both much stricter conditions being placed on admission to Holy Communion and the maintenance of traditional discipline within the established church. ... Lesser transgressors could be ordered by the kirk session to stand before the congregation for up to three Sundays, sometimes wearing sackcloth, and publicly acknowledge their sins before 'being subjected to a "rant" from the minister'.

- Beaulieu, Geoffrey of; Chartres, William of (29 November 2013). The Sanctity of Louis IX: Early Lives of Saint Louis by Geoffrey of Beaulieu and William of Chartres. Cornell University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780801469145.

- "Cilice". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2012-06-30.

- Ian Hodder, "Çatalhöyük: The Leopard's Tale", Thames & Hudson, 2006.

- Barlow, Frank (2002). Thomas Becket. London: The Folio Society. pp. 299, 314.

- "Opus Dei". opusdei.us. 17 May 2006.

- Allen 2006, pp. 165, 169, 171–173.

- Allen 2006, p. 173.

- Ice, Roy E. (11 March 2017). "Sackcloth". St Paul's United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 27 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Allen 2006, pp. 162–163.

- Allen Jr., John (2006). Opus Dei: An Objective Look Behind the Myths and Reality of the Most Controversial Force in the Catholic Church. Double Day. ISBN 9780385514507.

External links

| Look up cilice in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1910). . Catholic Encyclopedia. 7. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- On the Latin word cilicium (with photograph of a 16c hairshirt)

- Suffering and Sainthood in the Catholic Church The importance of Penance and Mortification for those who desire to become a Catholic Saint