Lactantius

Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (c. 250 – c. 325) was an early Christian author who became an advisor to the first Christian Roman emperor, Constantine I, guiding his religious policy as it developed,[1] and a tutor to his son Crispus. His most important work is the Institutiones Divinae ("The Divine Institutes"), an apologetic treatise intended to establish the reasonableness and truth of Christianity to pagan critics.

He is best known for his apologetic works, widely read during the Renaissance by humanists who called Lactantius the "Christian cicero". Also widely attributed to Lactantius is the poem The Phoenix, which is based on the myth of the phoenix from Oriental mythology. Though the poem is not clearly Christian in its motifs, modern scholars have found some literary evidence in the text to suggest the author had a Christian interpretation of the eastern myth as a symbol of resurrection.[2]

Biography

Lactantius, a Latin-speaking North African of Berber origin,[3][4][5][6] was not born into a Christian family. He was a pupil of Arnobius who taught at Sicca Veneria, an important city in Numidia. In his early life, he taught rhetoric in his native town, which may have been Cirta in Numidia, where an inscription mentions a certain "L. Caecilius Firmianus".[7]

Lactantius had a successful public career at first. At the request of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, he became an official professor of rhetoric in Nicomedia; the voyage from Africa is described in his poem Hodoeporicum (now lost[8]). There, he associated in the imperial circle with the administrator and polemicist Sossianus Hierocles and the pagan philosopher Porphyry; he first met Constantine, and Galerius, whom he cast as villain in the persecutions.[9] Having converted to Christianity, he resigned his post[10] before Diocletian's purging of Christians from his immediate staff and before the publication of Diocletian's first "Edict against the Christians" (February 24, 303).[11]

As a Latin rhetor in a Greek city, he subsequently lived in poverty according to Saint Jerome and eked out a living by writing until Constantine I became his patron. The persecution forced him to leave Nicomedia, perhaps re-locating to North Africa. The Emperor Constantine appointed the elderly Lactantius Latin tutor to his son Crispus in 309-310 who was probably 10-15 years old at the time.[12] Lactantius followed Crispus to Trier in 317, when Crispus was made Caesar (lesser co-emperor) and sent to the city. Crispus was put to death by order of his father Constantine I in 326, but when Lactantius died and under what circumstances are unknown.[13]

Writing

Like so many of the early Christian authors, Lactantius depended on classical models. The early humanists called him the "Christian Cicero" (Cicero Christianus).[13] A translator of the Divine Institutes wrote: "Lactantius has always held a very high place among the Christian Fathers, not only on account of the subject-matter of his writings, but also on account of the varied erudition, the sweetness of expression, and the grace and elegance of style, by which they are characterized."[14]

He wrote apologetic works explaining Christianity in terms that would be palatable to educated people who still practiced the traditional religions of the Empire. He defended Christian beliefs against the criticisms of Hellenistic philosophers. His Divinae Institutiones ("Divine Institutes") were an early example of a systematic presentation of Christian thought.

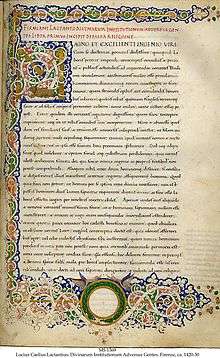

He was considered somewhat heretical after his death, but Renaissance humanists took a renewed interest in him, more for his elaborately rhetorical Latin style than for his theology. His works were copied in manuscript several times in the 15th century and were first printed in 1465 by the Germans Arnold Pannartz and Konrad Sweynheim at the Abbey of Subiaco. This edition was the first book printed in Italy to have a date of printing, as well as the first use of a Greek alphabet font anywhere, which was apparently produced in the course of printing, as the early pages leave Greek text blank. It was probably the fourth book ever printed in Italy. A copy of this edition was sold at auction in 2000 for more than $1 million.[15]

Prophetic exegesis

Like many writers in the first few centuries of the early church, Lactantius took a premillennialist view, holding that the second coming of Christ will precede a millennium or a thousand-year reign of Christ on earth. According to Charles E. Hill, "With Lactantius in the early fourth century we see a determined attempt to revive a more “genuine” form of chiliasm."[16] Lactantius quoted the Sibyls extensively (although the Sibylline Oracles are now considered to be pseudepigrapha). Book VII of The Divine Institutes indicates a familiarity with Jewish, Christian, Egyptian and Iranian apocalyptic material.[17]

None of the fathers thus far had been more verbose on the subject of the millennial kingdom than Lactantius or more particular in describing the times and events preceding and following. He held to the literalist interpretation of the millennium, that the millennium originates with the second advent of Christ and marks the destruction of the wicked, the binding of the devil and the raising of the righteous dead.[18]

He depicted Jesus reigning with the resurrected righteous on this earth during the seventh thousand years prior to the general judgment. In the end, the devil, having been bound during the thousand years, is loosed; the enslaved nations rebel against the righteous, who hide underground until the hosts, attacking the Holy City, are overwhelmed by fire and brimstone and mutual slaughter and buried altogether by an earthquake: rather unnecessarily, it would seem, since the wicked are thereupon raised again to be sent into eternal punishment. Next, God renews the earth, after the punishment of the wicked, and the Lord alone is thenceforth worshiped in the renovated earth.[19]

Lactantius confidently stated that the beginning of the end would be the fall, or breakup, of the Roman Empire.[20] However, this view fell out of favor with the conversion of Constantine and the improved lot of Christians: "Many Christians felt that any expectation of the downfall of the empire was as disloyal to God as it was to Rome."[17]

Attempts to determine the time of the End were viewed as in contradiction to Acts 1:7: "It is not for you to know the times or seasons that the Father has established by his own authority,"[17] and Mark 13:32: "But of that day or hour, no one knows, neither the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father."

Works

- De opificio Dei ("The Works of God"), an apologetic work, written in 303 or 304 during Diocletian's persecution and dedicated to a former pupil, a rich Christian named Demetrianius. The apologetic principles underlying all the works of Lactantius are well set forth in this treatise.[13]

- Institutiones Divinae ("The Divine Institutes"), written between 303 and 311.[13] This is the most important of the writings of Lactantius. It was "one of the first books printed in Italy and the first dated Italian imprint."[21] As an apologetic treatise, it was intended to point out the futility of pagan beliefs and to establish the reasonableness and truth of Christianity as a response to pagan critics. It was also the first attempt at a systematic exposition of Christian theology in Latin and was planned on a scale sufficiently broad to silence all opponents.[22] Patrick Healy notes, "The strengths and the weakness of Lactantius are nowhere better shown than in his work. The beauty of the style, the choice and aptness of the terminology, cannot hide the author's lack of grasp on Christian principles and his almost utter ignorance of Scripture."[13] Included in this treatise is a quote from the nineteenth of the Odes of Solomon, one of only two known texts of the Odes until the early twentieth century.[23] However, his mockery of the idea of a round earth[24] was criticised by Copernicus as "childish".[25]

- An Epitome of the Divine institutes is a summary treatment of the subject.[14]

- De ira Dei ("On the Wrath of God" or "On the Anger of God"), directed against the Stoics and Epicureans.[14]

- De mortibus persecutorum ("On the Deaths of the Persecutors") has an apologetic character but has been treated as a work of history by Christian writers. The point of the work is to describe the deaths of the persecutors of Christians before Lactantius (Nero, Domitian, Decius, Valerian, Aurelian) and the contemporaries of Lactantius himself: Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, Maximinus. This work is taken as a chronicle of the last and greatest of the persecutions in spite of the moral point that each anecdote has been arranged to tell. Here, Lactantius preserves the story of Constantine's vision of the Chi Rho before his conversion to Christianity. The full text is found in only one manuscript, which bears the title Lucii Caecilii liber ad Donatum Confessorem de Mortibus Persecutorum.[13]

- Widely attributed to Lactantius although it shows only cryptic signs of Christianity, the poem The Phoenix (de Ave Phoenice) tells the story of the death and rebirth of that mythical bird. That poem in turn appears to have been the principal source for the famous Old English poem to which the modern title The Phoenix is given.

- Opera ("Works") A second edition printed in the monastery at Subiaco, Lazio, is still extant. It remained in Italy until the late eighteenth century, when it was known to be in the library of Prince Vincenzo Maria Carafa in Messina. The Bodleian Library in Oxford, England, acquired this volume in 1817.[26]

See also

References

- His role is examined in detail in Elizabeth DePalma Digeser, The Making of a Christian Empire: Lactantius and Rome, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2000.

- White, Carolinne. Early Christian Latin Poets.

- Serralda, Vincent; Huard, André (1984). Le Berbère-- lumière de l'Occident (in French). Nouvelles Editions Latines. p. 56. ISBN 9782723302395.

- Annales de la Société d'histoire et d'archéologie de l'arrondissement de Saint-Malo (in French). 1957. p. 83.

- Manceron, Gilles; Aïssani, Farid (1996). Algérie: comprendre la crise (in French). Editions Complexe. p. 161. ISBN 9782870276617.

- Dérives (in French). 1985. p. 15.

- Harnack, Chronologie d. altchr. Lit., II,416

- Conte, Gian Biagio (1999). Latin Literature: A History. Baltimore: JHU Press. p. 640. ISBN 0-8018-6253-1. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- Paul Stephenson, Constantine, Roman Emperor, Christian Victor, 2010:104.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (15th ed.). 1993.

- Stephenson 2010:106.

- Barnes, Timothy, Constantine: Dynasty, Religion and Power in the Later Roman Empire, 2011, p. 177-8.

-

- W. Fletcher (1871). The Works of Lactantius.

- "Lot 65 Sale 6417 LACTANTIUS, Lucius Coelius Firmianus (c. 240–c. 320). Opera". Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- Hill, Charles E., "Why the Early Church Finally Rejected Premillennialism", Modern Reformation, Jan/Feb 1996, p. 16

- McGinn, Bernard. Visions of the End, Columbia University Press, 1998 ISBN 9780231112574

- Froom 1950, pp. 357-358.

- Froom 1950, pp. 358.

- Froom 1950, pp. 356-357.

- "The Rubrics of the First Book of Lactantius Firmianus's On the Divine Institutes Against the Pagans Begin". World Digital Library. 2011-10-17. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Lactantius The Divine Institutes, translated by Mary Francis McDonald Catholic University of America Press (1964)

- Charlesworth, James Hamilton. The Odes of Solomon. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1973, pp. 1, 82

- Lactantius, Divine Institutes, Book III Chapter XXIV

- Nicholas Copernicus (1543), The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres

- Polonsky Foundation Digitization Project: full scan of Lucius Coelius Firmianus Lactantius, Opera Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine hosted by the Bodleian Libraries (bodleian.ox.ac.uk) Provenance information: http://incunables.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/record/L-002 Accessed 13 July 2015.

Sources

- Froom, LeRoy (1950). The Prophetic Faith of our Fathers. 1. Archived from the original (DjVu and PDF) on 2014-11-06. Retrieved 2014-03-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Lactantius |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius. |

- Lactantius: links to primary texts and secondary sources

- Lactantius: text, concordances and frequency list

- Opera Omnia

- Bibliography of Lactantius: compiled by Jackson Bryce

- Lactantius, The Divine Institutes