Homo unius libri

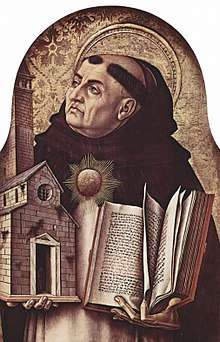

Homo unius libri ("(a) person of one book") is a Latin phrase attributed to Thomas Aquinas in a literary tradition going back to at least the 17th century, bishop Jeremy Taylor (1613–1667) being the earliest known writer in English to have done so. Saint Thomas Aquinas is reputed to have employed the phrase "hominem unius libri timeo" (meaning "I fear the person of a single book").

There are other attributions, and variants of the phrase. Variants include cave for timeo, and virum ("man") or lectorem ("reader") for hominem. The Concise Dictionary of Foreign Quotations (London 1998), attributes the quote to Augustine of Hippo. It has also been attributed to Pliny the Younger, Seneca or Quintilian, but the existence of the phrase cannot be substantiated as predating the early modern period.[1]

The phrase was in origin a dismissal of eclecticism, i.e. the "fear" is of the formidable intellectual opponent who has dedicated himself to and become a master in a single chosen discipline; however, the phrase today most often refers to the interpretation of expressing "fear" of the opinions of the illiterate man who has "only read a single book".[2] The phrase was used by Methodist founder John Wesley, referring to himself, with "one book" taken to mean the Bible.[3].

Interpretations

Mastery of a single topic

The literary critic Clarence Brown described the phrase in his introduction to a novel by Yuri Olesha:

[Aquinas's] words are generally quoted today in disparagement of the man whose mental horizons are limited to one book. Aquinas, however, meant that a man who has thoroughly mastered one good book can be dangerous as an opponent. The Greek poet Archilochus meant something like this when he said that the fox knows many things but the hedgehog knows one big thing.[4]

The poet Robert Southey recalled the tradition in which the quotation became embedded:

When St Thomas Aquinas was asked in what manner a man might best become learned, he answered, 'By reading one book'; 'meaning,' says Bishop Taylor, 'that an understanding entertained with several objects is intent upon neither, and profits not.[5] The homo unius libri is indeed proverbially formidable to all conversational figurantes. Like your sharp-shooter, he knows his piece perfectly, and is sure of his shot.[6]

By way of comparison, Southey quotes Lope de Vega's Isidro de Madrid expressing a similar sentiment,

- For a noteworthy student is he,

- The man of a single book.

- For when they were not filled up

- With so many extraneous books,

The writer and naturalist Charles Kingsley, following the tradition laid down by Gilbert White in The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne (1789), also invoked the proverb in favour of knowing completely one small area. "A lesson is never learnt till it is learnt over many times, and a spot is best understood by staying in it and mastering it. In natural history the old scholar's saw Cave hominem unius libri[7] may be paraphrased by, 'He is a thoroughly good naturalist who knows one parish thoroughly.'"[8]

John Wesley invoked the phrase in this sense and declared himself to be a "homo unius libri", the "one book" being the Bible.[3] Like Methodists in the strict Wesleyan tradition of depending upon the One Book, many seventeenth-century and modern radical Protestants have prided themselves on being homines unius libri. The poet William Collins in his deranged condition, met by chance his old friend Samuel Johnson, who found Collins carrying a New Testament. "I have but one book," said Collins, "but it is the best".[9]

Narrow learning

Edward Everett applied the remark "not only to the man of one book, but also to the man of one idea, in whom the sense of proportion is lacking, and who sees only that for which he looks".[10]

Joseph Needham, in the general conclusions to his Science and Civilisation in China series, observed of the saying, "It could mean that this man has only read one book, has only written one book, does not possess more than one book, or puts his faith in one book only. The fear that is felt may be on behalf of the man himself. Having read so little he is quite at the mercy of his one book!"[11]

Limited success as an author

In Samuel Butler's The Way of All Flesh (1903), a publisher uses the phrase to describe the novel's protagonist.[12] Butler also records that his own publisher, Trübner, applied the phrase to him to express doubts in his literary prospect, the "one book" of Butler's in this case being Erewhon.[13]

Notes

- Andreas Fritsch, "Timeo lectorem unius libri", Vox Latina 19 (1983), 309 ff. Pliny did express a comparable sentiment. "CAVE AB HOMINE UNIUS LIBRI. Never was this old Latin proverb of greater import, never did it convey a deeper meaning than in this, our own century, when everyone appears to have become an "heluo librorum." Since most men seem to know a little of everything and not much of anything, the man of one book, the reader who is intimate with one great author, whom he has chosen for his favorite, who has imbibed the spirit of his model, and fashioned almost insensibly his own mind after that of his exemplar, is, indeed, a formidable antagonist. Pliny tells us that we should read much, but not many books." The Stylus, Volume III, Number 3, 1 April 1885. newspapers.bc.edu

- In The Portable Twentieth-Century Russian Reader, Clarence Brown, editor (Penguin) 1985, p. 246; see The Hedgehog and the Fox for further discussion of this phrase.

- "in 1730 I began to be homo unius libri, to study (comparatively) no book but the Bible." Letter to John Newton, May 14, 1765. He wrote privately on another occasion

- "I receive the written word as the whole and sole rule of my faith..... From the very beginning, from the time that four young men united together, each of them was homo unius libri... They had one, and only one, rule of judgement with which to regard all their tempers, words and actions; namely, the oracles of God."

- "He came from heaven; He hath written it down in a book. O give me that Book! At any price, give me the Book of God. I have it; here is knowledge enough for me. Let me be homo unius libri!"

- In The Portable Twentieth-Century Russian Reader, Clarence Brown, e ditor (Penguin) 1985, p. 246; see The Hedgehog and the Fox for further discussion of this phrase.

- Jeremy Taylor, Life of Christ, Pt. II. Sect. II. Disc. II. 16.

- Robert Southey, The Doctor, &c, (1848), Interchapter VII (e-text). Southey's version of the quote was taken up by John Bartlett (1820-1905), the compiler of Bartlett's Familiar Quotations (ninth edition, 1902, p. 853).

- "Beware the man of one book."

- Charles Kingsley, At Last: A Christmas in the West Indies, 1871.

- Collins' epitaph in Chichester Cathedral reads, in part: Sought on one book his troubled mind to rest, And wisely deemed the book of God the best.The Johnson anecdote and Collins' epitaph are reported in Walsh 1892 s.v., "Book, Beware of the man of one".

- Reported in William Shepard Walsh, Handy-book of Literary Curiosities, 1892, s.v., "Book, Beware of the man of one".

- Science and Civilisation in China, "50 General Conclusions and Reflections", p. 97.

- Ernest Pontifex, who is a writer with only one commercially or critically successful work: "'Mr Pontifex,' he said, 'is a homo unius libri, but it doesn't do to tell him so.'" Butler, Samuel (1917). The Way of All Flesh. E.P. Dutton & Company. p. 463.

- The Note-books of Samuel Butler, ed. H. F. Jones (1912), p. 155

- Eugene H. Ehrlich, Amo Amas Amat and More: How to use Latin to Your Own Advantage and the Astonishment of Others, p. 279. "An observation attributed to Aquinas"

External links

![]()