Participism

Participism is a libertarian socialist political philosophy consisting of two independently created economic and political systems: participatory economics ("parecon") and participatory politics ("parpolity"). Participism is intended as an alternative to both capitalism and centrally-planned state socialism. Participism has significantly informed the International Organization for a Participatory Society.

Overview

Advocates of participism envision remaking all of human society from the bottom up according to principles of direct participatory democracy and replacing economic and social competition with cooperation. Supporters of what is termed a "participatory society" support the eventual dissolution of the centralized state, markets, and money (in its current form) placing it in the tradition of anti-authoritarian libertarian socialism. To elucidate their vision for a new society, advocates of participism categorize their aspirations into what they term a "liberating theory".

Liberating theory is a holistic framework for understanding society that looks at the whole of society and the interrelations among different parts of people's social lives. Participism groups human society into four primary "spheres", all of which are set within an international and ecological context, and each of which has a set of defining functions:

- The political sphere: policy-making, administration, and collective implementation.

- The economic sphere: production, consumption, and allocation of the material means of life.

- The kinship sphere: procreation, nurturance, socialisation, gender, sexuality, and organisation of daily home life.

- The community sphere: development of collectively shared historical identities, culture, religion, spirituality, linguistic relations, lifestyles, and social celebrations.

Within each sphere there are two components. The first component is the Human Centre, the collection of people living within a society. Each person has needs, desires, personalities, characteristics, skills, capacities, and consciousness. The second component is the Institutional Boundary, all of society’s social institutions that come together to form interconnected roles, relationships, and commonly held expectations and patterns of behaviour, that produce and reproduce societal outcomes. These institutions come together to help shape who people are as individuals.

Participatory politics

Parpolity is the political system first proposed by Stephen R. Shalom, professor of political science at William Paterson University in New Jersey. Shalom has stated that Parpolity is meant as a long range vision of where social justice should reach its apex within the field of politics and should complement the level of participation in the economy with an equal degree of participation in policy and administrative matters.

The values on which parpolity is based are:

The goal, according to Shalom, is to create a political system that will allow people to participate, as much as possible in a direct and face to face manner. The proposed decision-making principle is that every person should have say in a decision proportionate to the degree to which she or he is affected by that decision.

The vision is critical of aspects of modern representative democracies arguing that the level of political control by the people isn't sufficient. To address this problem parpolity suggests a system of Nested Councils, which would include every adult member of a given society.

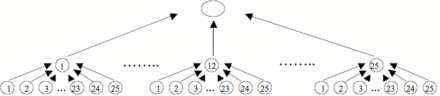

In a country or society run according to participism, there would be local councils of voting citizens consisting of 25-50 members. These local councils would be able to pass any law that affected only the local council. No higher council would be able to override the decisions of a lower council, only a council court would be able to challenge a local law on human rights grounds. The councils would be based on consensus, though majority votes are allowed when issues cannot be agreed upon.

Each local council would send a delegate to a higher level council, until that council fills with 25-50 members. These second level councils would pass laws on matters that effect the 625 to 2500 citizens that it represents. A delegate to a higher level council is bound to communicate the views of her or his sending council, but is not bound to vote as the sending council might wish. Otherwise, Shalom points out that there is no point in having nested councils, and everyone might as well vote on everything. A delegate is recallable at any time by her or his sending council. Rotation of delegates would be mandatory, and delegates would be required to return to their sending councils frequently.

The second level council sends a delegate to a third level council, the third level councils send delegates to a fourth level and so on until all citizens are represented. Five levels with 50 people on every council would represent 312,500,000 voters (around the population of the United States). However, the actual number of people included would be even higher, given that young children would not be voting. Thus, with a further sixth level nested council, the entire human population could be included. This would not however be equatable to a global world state, but rather would involve the dissolution of all existing nation-states and their replacement with a worldwide confederal "coordinating body" made of delegates immediately recallable by the nested council below them.

Lower level councils have the opportunity to hold referendums at any time to challenge the decisions of a higher level council. This would theoretically be an easy procedure, as when a threshold of lower level councils call for a referendum, one would then be held. Shalom points out that sending every issue to lower level councils is a waste of time, as it is equivalent to referendum democracy.

There would be staff employed to help manage council affairs. Their duties would perhaps include minute taking and researching issues for the council. These council staff would work in a balanced job complex defined by a participatory economy.

Participatory economics

Parecon (participatory economics) is an economic system proposed primarily by activist and political theorist Michael Albert and radical economist Robin Hahnel. It uses participatory decision making as an economic mechanism to guide the production, consumption and allocation of resources in a given society. It is described as "an anarchistic economic vision", and a form of socialism, the means of production are owned in common. The theory is proposed as an alternative to both contemporary capitalist market economies and centrally planned socialism. It distinguishes between two parts of the working class. The 'coordinator class' that does the conceptual, creative and managerial work and the rest of the class doing rote work. This situation is deemed 'coordinatorism', which the theory claims it to be a major flaw with Marxism.[1]:4-8

The underlying values that parecon seeks to implement are equity, solidarity, diversity, workers' self-management and efficiency. (Efficiency here means accomplishing goals without wasting valued assets.) It proposes to attain these ends mainly through the following principles and institutions:

- workers' and consumers' councils utilizing self-managerial methods for making decisions,

- balanced job complexes,

- remuneration according to effort and sacrifice, and

- participatory planning.

In place of money parecon would have a form of currency in which personal vouchers or "credits" would be awarded for work done to purchase goods and services. Unlike money, credits would disappear upon purchase, and would be non-transferable between individuals, making bribery and monetary theft impossible. Also, the only items or services with a price attached would most likely be those considered wants or non-essentials and anything deemed a need would be completely free of charge (e.g.: health care, public transportation).

Albert and Hahnel have stressed that parecon is only meant to address an alternative economic theory and must be accompanied by equally important alternative visions in the fields of politics, culture and kinship. The authors have also discussed elements of social anarchism in the field of politics, polyculturalism in the field of culture, and feminism in the field of family/kinship and gender relations as being possible foundations for future alternative visions in these other spheres of society. Since the publication of Albert's book "Parecon", other thinkers have come forward and incorporated these concepts which have rounded participism into a more fully formed political and social ideology.

Feminist kinship

See also Nurture kinship and Free love

Outside of both political and economic relations there still exists the sphere of human kinship. Participism sees this as a vital component in a liberated society and applies feminist principles to this aspect of human relations. Feminist kinship relations are seen to seek to free people from oppressive definitions that have been socially imposed and to abolish all sexual divisions of labour and sexist and heterosexist demarcation of individuals according to gender and sexuality.

Participism holds that a participatory society must be respectful on an individual’s nature, inclinations, and choices and all people must be provided with the means to pursue the lives they want regardless of their gender, sexual orientation, or age. Feminist kinship relations are dependent on the liberation of women, LGBTQ persons, youth, the elderly, and intersex (hermaphroditic and pseudohermaphroditic) individuals.

To extend liberation into daily home life, a participatory society aims to provide the means for traditional couples, single parents, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, transgender, and intersex parents, communal parenting, polygamy (especially polyandry), polyamorous and multiple parenting arrangements to develop and flourish. It is believed that within the home and the community, the task of raising children must be elevated in status. Highly personalised interaction between children and adults should be encouraged, and responsibilities for these interactions must be distributed equitably throughout society without segregating tasks by gender. A participatory society would provide parents with access to high quality day-care, flexible work hours, and parental leave options allowing them to play a more active role in the lives of their children.

The liberation of women and society from patriarchal and heteronormative oppression, according to participism, requires total reproductive freedom. Society must provide all members with the right to family planning, without shame or guilt for performing or soliciting an abortion or for engaging in alternative sexual behavior and without fear of sterilization or economic deprivation; the right to have or not to have children and to terminate undesired pregnancies through unhindered access to birth control and unregulated abortion, respectively; and the right to comprehensive sexual education and healthcare that provide every citizen with information and resources to live a healthy and fulfilling sex life.

In such sex-positive participatory societies the full exploration of human sexuality, with the possible exception of child sexuality, would be accepted and embraced as normative. Participism encourages the exercise of and experimentation of different forms of sexuality by consenting partners.

Polycultural community

Human society is held to have long and brutal history of conquest, colonisation, genocide, and slavery which cannot be transcended easily. To begin the step-by-step process of building a new historical legacy and set of behavioural expectations between communities, a participatory society would construct intercommunalist institutions to provide communities with the means to assure the preservation of their diverse cultural traditions and to allow for their continual development. With polycultural intercommunalism, all material and psychological privileges that are currently granted to a section of the population at the expense of the dignity and standards of living for oppressed communities, as well as the division of communities into subservient positions according to culture, ethnicity, nationality, and religion, will be dissolved.

The multiplicity of cultural communities and the historical contributions of different communities would be respected, valued, and preserved by guaranteeing each sufficient material and communicative means to reproduce, self-define, develop their own cultural traditions, and represent their culture to all other communities. Through construction of intercommunalist relations and institutions that guarantee each community the means necessary to carry on and develop their traditions, a participatory society assists eliminating negative inter-community relations and encourages positive interaction between communities that can enhance the internal characteristics of each.

In a participatory society, individuals would be free to choose the cultural communities they prefer and members of every community would have the right of dissent and to leave. Intervention would not be permitted except to preserve this right for all. Those outside a community would also be free to criticize cultural practices that they believe violate acceptable social norms, but the majority would not have the power to impose its will on a vulnerable minority.

Criticisms

Anarchism

Certain anarchists of the libcom community (an internet community of libertarian communists) have criticized the parpolity aspect of participism for deciding beforehand the scale and scope of the councils whilst only practice, they argue, can accurately indicate the size and scale of anarchist confederations and other organizational platforms, especially since each region is unique with unique residents and unique solutions and unique wants. Anarchists argue that such blueprints containing detailed information are either dangerous or pointless. Furthermore, some anarchists have criticized the potential use of referendums to challenge decisions taken by higher councils as this implies both a top-down structure and an absence of vis-à-vis democracy as they argue that referendums are not participatory.[2]

They have also criticized the enforcement of laws passed by councils rather than the use of supposed voluntary custom or customary law which develops through mutual recognition rather than being enforced by an external authority, as they argue the laws passed by such councils would need to be.[2]

Capitalism

The criticism of socialism could be applied to participism as well, as advocates of capitalism object to the absence of a market and private property in a hypothetical participatory society. However, in a debate with David Horowitz, Michael Albert argued that those criticisms could not apply to parecon, as it was especially designed to take them into account. New specific criticisms should then be formulated. For instance, in an answer to the comments of David Kotz and John O'Neill about one of their articles on the subject, Albert and Hahnel assert that they designed parecon understanding "that knowledge is distributed unequally throughout society",[3] hypothetically answering to the famous criticisms of Friedrich Von Hayek on the possibility of planning.

See also

References

- Albert, Michael; Hanhel, Robin (1990). Looking Forward: Participatory Economics for the Twenty First Century. South End Press. ISBN 9780896084056.

- Parecon or libertarian communism?. libcom.org. Retrieved on 2013-07-12.

- Albert, Michael and Robin Hahnel. 2002. "Reply". In Science and Society, vol. 66, no. 1, p. 26, [online]. http://gesd.free.fr/albert.pdf

External links

- Participatory economics website

- Vancouver Participatory Economics Collective

- Old Market Autonomous Zone (Winnipeg)

- Article about Parpolity: Political Vision for a Good Society by Stephen R. Shalom at the Wayback Machine (archived 2008-10-24)

- Stephen Shalom interviewed about Parpolity by Vancouver COOP Radio

- MP3 Audio of above interview with Stephen Shalom at the Wayback Machine (archived 2007-08-07)

- Projects for a Participatory Society web site at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2005-04-21)

- International Organization for a Participatory Society