Raid on Nassau

The Raid on Nassau, on the Bahamian island of New Providence, was a privately raised Franco-Spanish expedition against the English taking place in October 1703, during the War of the Spanish Succession; it was a Franco-Spanish victory, leading to Nassau's brief occupation, then its destruction.[1][2] The joint Bourbon invasion was led by Blas Moreno Mondragón and Clause Le Chesnaye, with the attack focusing on Nassau, the capital of the English Bahamas, an important base of privateering for English corsairs in the Cuban and Saint Domingue's Caribbean seas. The town of Nassau was quickly taken[3] and sacked, plundered and burnt down.[2][3][4] The fort of Nassau was dismantled, and the English governor, with all the English soldiers were carried off prisoners.[1] A year later, Sir Edward Birch, the new English governor, upon landing in Nassau, was so distraught at the ruin he found, that he returned to England after only a few months, without "unfurling his company-issued commission".[2][5]

| Raid on Nassau | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

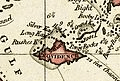

Island of New Providence, home to Nassau, in the Gulf of Providence, in the islands of the Bahamas [See further map below for context.] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 frigates 300~400 men | 300 men | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| few |

100 civilians killed 100 prisoners 22 guns | ||||||

Raid

Leaders of the island colonies of Santiago de Cuba and Saint-Domingue viewed Nassau as a menace, and raised a joint expedition of Spanish soldiers and French boucaniers, sending them to Nassau in October 1703 aboard two frigate in the command of the officers Blas Moreno Mondragón and Claude Le Chesnaye.[1] They surprised 250 English inhabitants at the capital of New Providence slaughtering more than 100, taking 80-100 prisoners, seizing 22 guns, throwing down all the fortifications, and returning to Santiago de Cuba a few days later with the prisoners and 13 ships as prizes.[2] Among the prisoners was Governor Ellis Lightwood.[2][1]

Aftermath

The English inhabitants retired to the woods until the danger was over. Returning they found the island completely ruined and reduced to a desert, they found means to remove themselves to other settlements. England had taken to little concern in the affairs of New Providence, that they did not even know of the catastrophe which had happened. Edward Birch was appointed as new governor, but when he went to Nassau found it entirely abandoned; so he was obliged to return home without having opened his commission.[5] Another enemy raid in 1706 left only twenty-seven families still cringing inside makeshift huts on New Providence Island, and no more than 400 to 500 English residents scattered considerable distress from more descents during the remainder of this conflict, while their scant overseas trade dried up and no new governors or assistance came out from England. Birch saw the inhabitants without "a shift to cover their nakedness" that he did not bother to unroll his commission before taking ship back to England.[4][6] John Graves (who had come to the Bahamas with Thomas Bridges in 1686 and served for at time as colonial secretary) reported in 1706 that the few New Providence survivors "lived scatteringly in little hutts, ready upon any assault to secure themselves in the woods."[4]

References and notes

- Marley (2005), p. 7.

- Marley (1998), p. 226.

- Albury, p. 55.

- Craton & Saunders, p. 103.

- Sale, Psalmanazar & Bower, p. 290.

- Oldmixon, p. 21.

Bibliography

- Oldmixon, John (1966). The History of the Isle of Providence. Providence Press.

- Albury, Paul (1976). The Story of the Bahamas. St. Martins Press. ISBN 0312762658.

- Marley, F. David (2005). "Bahamas". Historic Cities of the Americas: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Vol. 1: The Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 3–15. ISBN 1576070271. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- Craton, Michael & Saunders, Gail (1999). Islanders in the Stream: A History of the Bahamian People. Vol. 1: From Aboriginal Times to the End of Slavery. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0820321222.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Marley, F. David (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0874368375.

- Sale, George; Psalmanazar, George & Bower, Archibald (1747). "Millar". The Modern Part of A Universal History, From the Earliest. Vol. 36. ISBN 0874368375.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

Further reading

- Baker, P. (2001). Bahamas, Turks & Caicos. Lonely Planet Publishing. ISBN 1864501995.