Sprint (running)

Sprinting is running over a short distance in a limited period of time. It is used in many sports that incorporate running, typically as a way of quickly reaching a target or goal, or avoiding or catching an opponent. Human physiology dictates that a runner's near-top speed cannot be maintained for more than 30–35 seconds due to the depletion of phosphocreatine stores in muscles, and perhaps secondarily to excessive metabolic acidosis as a result of anaerobic glycolysis.[1]

In athletics and track and field, sprints (or dashes) are races over short distances. They are among the oldest running competitions, being recorded at the Ancient Olympic Games. Three sprints are currently held at the modern Summer Olympics and outdoor World Championships: the 100 metres, 200 metres, and 400 metres.

At the professional level, sprinters begin the race by assuming a crouching position in the starting blocks before driving forward and gradually moving into an upright position as the race progresses and momentum is gained. The set position differs depending on the start. The use of starting blocks allows the sprinter to perform an enhanced isometric preload; this generates muscular pre-tension which is channelled into the subsequent forward drive, making it more powerful. Body alignment is of key importance in producing the optimal amount of force. Ideally the athlete should begin in a 4-point stance and drive forwards, pushing off using both legs for maximum force production.[2] Athletes remain in the same lane on the running track throughout all sprinting events,[1] with the sole exception of the 400 m indoors. Races up to 100 m are largely focused upon acceleration to an athlete's maximum speed.[2] All sprints beyond this distance increasingly incorporate an element of endurance.[3]

History

The first 13 editions of the Ancient Olympic Games featured only one event—the stadion race, which was a sprinting race from one end of the stadium to the other.[4] The Diaulos (Δίαυλος, "double pipe") was a double-stadion race, c. 400 metres (1,300 feet), introduced in the 14th Olympiad of the ancient Olympic Games (724 BC).

The modern sprinting events have their roots in races of imperial measurements which were later altered to metric: the 100 m evolved from the 100-yard dash,[5] the 200 m distance came from the furlong (or 1⁄8 mile),[6] and the 400 m was the successor to the 440-yard dash or quarter-mile race.[1]

Biological factors for runners

Biological factors that determine a sprinter's potential include:

- Height (minor factor)

- Muscular strength

- Adrenaline use

- Anaerobic respiration capacity

- Breathing

- Footspeed

- Proportion of fast twitch muscles[7]

- Leg length

- Pelvic width

Competitions

Common contemporary distances

60 m

- The 60 metres is normally run indoors, on a straight section of an indoor athletic track. Since races at this distance can last around six or seven seconds, having good reflexes and thus getting off to a quick start is more vital in this race than any other.

- This is roughly the distance required for a human to reach maximum speed and can be run with one breath. It is popular for training and testing in other sports (e.g., speed testing for American football, although 40 yards is more common there).

- The world record in this event is held by American sprinter Christian Coleman with a time of 6.34 seconds.

- 60-metres is used as an outdoor distance by younger athletes when starting sprint racing.

Note: Indoor distances are less standardized as many facilities run shorter or occasionally longer distances depending on available space. 60m is the championship distance.

100 m

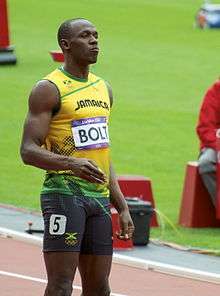

- The 100 metres sprint takes place on one length of the home straight of a standard outdoor 400 m track. Often, the world-record holder in this race is considered "the world's fastest man/woman." The current world record of 9.58 seconds is held by Usain Bolt of Jamaica and was set on 16 August 2009, at the 2009 World Athletics Championships. The women's world record is 10.49 seconds and was set by Florence Griffith-Joyner.

- World class male sprinters (sub 10.10s) need 41 to 50 strides to cover the whole 100 metres distances.[8]

200 m

- The 200 metres begins on the curve of a standard track (where the runners are staggered in their starting position, to ensure that they all run the same distance), and ends on the home straight. The ability to "run a good bend" is key at the distance, as a well conditioned runner will typically be able to run 200 m in an average speed higher than their 100 m speed. Usain Bolt, however, ran 200 m in the world-record time of 19.19 sec, an average speed of 10.422 m/s, whereas he ran 100 m in the world-record time of 9.58 sec, an average speed of 10.438 m/s.

- Indoors, the race is run as one lap of the track, with only slightly slower times than outdoors.

- A slightly shorter race (but run on a straight track), the stadion, was the first recorded event at the ancient Olympic Games and the oldest known formal sports event in history.

- The world record in this event is 19.19 seconds, held by Usain Bolt and was set on 20 August 2009, at the 2009 World Athletics Championships.

400 m

- The 400 metres is one lap around the track on the inside lane. Runners are staggered in their starting positions to ensure that everyone runs the same distance. While this event is classified as a sprint, there is more scope to use tactics in the race; the fact that 400 m times are considerably more than four times a typical 100 m time demonstrates this.

- The world record is currently held by Wayde van Niekerk with a time of 43.03 seconds in Rio Olympic 2016 in 400m final[9]

Relay

- The 4×100 metres relay is another prestigious event, with an average speed that is quicker than the 100 m, as the runners can start moving before they receive the baton. The world record in this event is 36.84 seconds, held by the Jamaican team as set 11 August 2012 at the Games of the XXX Olympiad held in London.

- The 4x400 metres relay is often held at track and field meetings, and is by tradition the final event at major championships.

Historical and uncommon distances

50 yards (45.72 m)

- The event was a common event for most American students, because it was one of the standardized test events as part of the President's Award on Physical Fitness.[10]

50 m

The 50 metres is an uncommon event and alternative to the 60 metres. Donovan Bailey holds the men's world record with a time of 5.56 seconds and Irina Privalova holds the women's world record with a time of 5.96 seconds.

60 yards (54.864 m)

- A rarely run sprinting event that was once more commonplace. The world record time of 5.99 is held by Lee McRae, and was set in 1987. The time is often used for American Football speed training.

55 m

The 55 metres is an uncommon event that resulted from the metrication of the 60 yards, and is an alternative to the 60 metres.

70 Yards

- An extremely rare sprinting event, that was occasionally run in the 1960s. The world record of 6.90 is held by Bob Hayes

100 yards (91.44 m)

- The outdoor standard in the English (imperial measured) speaking world. It was part of the Commonwealth Games up until 1966 and was the premier event in American high school sprinting until the NFHS changed to metric in 1980, now only a secondary distance to the 100 metres.

- The unofficial World Record Holder is Jamaican Asafa Powell with a time of 9.07 seconds.

150 m

.jpg)

- The informal distance of 150 metres (164.042 yards) can be used to work on a 100 m runner's stamina, or a 200 m runner's speed, and has been used as an exhibition distance. The distance was used in a race between 1996 Olympic champions, the 100 m gold medalist Donovan Bailey (Canada) and 200 m gold medalist Michael Johnson (USA). It was to decide which of the two was really the 'fastest man on earth' (see Bailey–Johnson 150-metre race).

- The informal distance was used for an exhibition race during the Manchester Great CityGames in as part of the 2009 Great Manchester Run (UK). Stars included Triple Olympic Champion Usain Bolt (Jamaica) alongside Ivory Williams (USA), Simeon Williamson (UK) and other international track stars. The female race included 400 m Olympic Champion, Christine Ohuruogu of Great Britain alongside Debbie Ferguson-McKenzie (Bahamas). Bolt ran the distance in a record time of 14.35 seconds.[11][12]

Stadion

The stadion, also known as the stade, was the standard short distance sprint in ancient Greece and ran the length of a stadium. However, stadiums could vary in size and there was apparently no definite standard length for them e.g. the stadium at Delphi measures 177 m and the one at Pergamon 210 m.[13]

300 m

- The 300 metres is another informal distance, which could be used to aid a 200m runner's stamina, or a 400m runner's speed. Currently the world's best for this event is 30.81 seconds, set by Wayde van Niekerk in Ostrava, Czech Republic in 2017.[14] The women's record is 35.30 seconds, set by Ana Guevara at altitude in Mexico City in 2003. Junior girls in several countries run this distance instead of the 400 metres.

Rules

The start

Starting blocks are used for all competition sprint (up to and including 400 m) and relay events (first leg only, up to 4x400 m).[15] The starting blocks consist of two adjustable footplates attached to a rigid frame. Races commence with the firing of the starter's gun.[15] The starting commands are "On your marks" and "Set".[15] Once all athletes are in the set position, the starter's gun is fired, officially starting the race. For the 100 m, all competitors are lined up side by side. For the 200 m, 300 m and 400 m, which involve curves, runners are staggered for the start.

In the rare event that there are technical issues with a start, a green card is shown to all the athletes. The green card carries no penalty. If an athlete is unhappy with track conditions after the "on your marks" command is given, the athlete must raise a hand before the "set" command and provide the Start referee with a reason. It is then up to the Start referee to decide if the reason is valid. In the event that the Start referee deems the reason invalid, a yellow card (warning) is issued to that particular athlete. In the event that the athlete is already on a warning the athlete is disqualified.

False starts

According to the IAAF rules, "An athlete, after assuming a full and final set position, shall not commence his starting motion until after receiving the report of the gun, or approved starting apparatus. If, in the judgement of the Starter or Recallers, he does so any earlier, it shall be deemed a false start."[15]

The 100 m Olympic Gold and Silver medallist Linford Christie of Great Britain famously had frequent false starts that were marginally below the legal reaction time of 0.1 seconds. Christie and his coach, Ron Roddan, both claimed that the false starts were due to Christie's exceptional reaction times being under the legal time. His frequent false starting eventually led to his disqualification from the 1996 Summer Olympics 100 m final in Atlanta, Georgia, US due to a second false start by Christie. Since January 2010, under IAAF rules, a single false start by an athlete results in disqualification. In 2012, a new development to the false start rule was added. Because certain athletes could be disqualified for twitching in the starting blocks but some athletes could make a twitch without the starter noticing and disqualifying the athlete, it was decided that twitching in the starting block while being in the 'set' position would only carry a maximum penalty of a yellow card or a warning. In order to instantly be disqualified for a false start, an athlete's hands must leave the track or their feet must leave the starting blocks, while the athlete is in their final 'set' position.

Lanes

For all Olympic sprint events, runners must remain within their pre-assigned lanes, which measure 1.22 metres (4 feet) wide, from start to finish.[16] The lanes can be numbered 1 through 8, 9, or rarely 10, starting with the inside lane. Any athlete who runs outside the assigned lane to gain an advantage is subject to disqualification. If the athlete is forced to run outside of his or her lane by another person, and no material advantage is gained, there will be no disqualification. Also, a runner who strays from his or her lane in the straightaway, or crosses the outer line of his or her lane on the bend, and gains no advantage by it, will not be disqualified as long as no other runner is obstructed.

The finish

The first athlete whose torso reaches the vertical plane of the closest edge of the finish line is the winner. To ensure that the sprinter's torso triggers the timing impulse at the finish line rather than an arm, foot, or other body part, a double Photocell is commonly used. Times are only recorded by an electronic timing system when both of these Photocells are simultaneously blocked. Photo finish systems are also used at some track and field events.

Sprint training

While genetics play a large role in one's ability to sprint,[17][18][19] athletes must be dedicated to their training to ensure that they can optimize their performances. Sprint training includes various running workouts, targeting acceleration, speed development, speed endurance, special endurance, and tempo endurance. Additionally, athletes perform intense strength training workouts, as well as plyometric or jumping workouts. Collectively, these training methods produce qualities which allow athletes to be stronger, more powerful, in hopes of ultimately running faster.

See also

- Sprint cycling

- Athletics at the Summer Olympics

- 60 metres at the Olympics

- 100 metres at the Olympics

- 200 metres at the Olympics

- 400 metres at the Olympics

- Sprint hurdles at the Olympics

- 400 metres hurdles at the Olympics

- 4×100 metres relay at the Olympics

- 4×400 metres relay at the Olympics

Notes and references

- 400 m Introduction. IAAF. Retrieved on 26 March 2010.

- 100 m – For the Expert. IAAF. Retrieved on 26 March 2010.

- 200 m For the Expert. IAAF. Retrieved on 26 March 2010.

- Instone, Stephen (15 November 2009). The Olympics: Ancient versus Modern. BBC. Retrieved on 23 March 2010.

- 100 m – Introduction. IAAF. Retrieved on 26 March 2010.

- 200 m Introduction. IAAF. Retrieved on 26 March 2010.

- Quinn, Elizabeth (2007-10-30). Fast and Slow Twitch Muscle Fibers About.com. Retrieved on 2009-02-01.

- Jad Adrian (6 March 2011). Complete Sprinting Technique. Retrieved on 30 April 2011

- "IAAF: World Records | iaaf.org". iaaf.org. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- "President's Council on Sports, Fitness & Nutrition (PCSFN)". HHS.gov. 10 January 2017.

- Bolt runs 14.35 sec for 150m; covers 50m-150m in 8.70 sec!. IAAF (2009-05-17). Retrieved on 2009-05-17.

- New World Best over 150m for Usain Bolt from Universal Sports on YouTube

- Spivey, Nigel, The Ancient Olympics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 111–112

- "Wayde van Niekerk breaks another Michael Johnson record". olympics.nbcsports.com. 2017-06-28. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- Competition Rules 2012-13, IAAF

- 2009 USATF Competition Rules, Rule 160(1)

- Lombardo, Michael P.; Deaner, Robert O. (2014-06-26). "You can't teach speed: sprinters falsify the deliberate practice model of expertise". PeerJ. 2: e445. doi:10.7717/peerj.445. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 4081292. PMID 25024914.

- Scott, Robert A.; Irving, Rachael; Irwin, Laura; Morrison, Errol; Charlton, Vilma; Austin, Krista; Tladi, Dawn; Deason, Michael; Headley, Samuel A.; Kolkhorst, Fred W.; Yang, Nan; North, Kathryn; Pitsiladis, Yannis P. (1 January 2010). "ACTN3 and ACE genotypes in elite Jamaican and US sprinters". Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 42 (1): 107–112. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181ae2bc0. PMID 20010124.

- Eynon, Nir; Hanson, Erik D.; Lucia, Alejandro; Houweling, Peter J.; Garton, Fleur; North, Kathryn N.; Bishop, David J. (1 September 2013). "Genes for elite power and sprint performance: ACTN3 leads the way". Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 43 (9): 803–817. doi:10.1007/s40279-013-0059-4. PMID 23681449.