Caribbean art

Caribbean art refers to the visual (including painting, photography, and printmaking) as well as plastic arts (such as sculpture) originating from the islands of the Caribbean (for mainland-Caribbean see Caribbean South America). Art in the Caribbean reflects thousands of years of habitation by Arawak, Kalinago, and other people of the Caribbean followed by waves of immigration, which included artists of European origins and subsequently by artists with heritage from countries all around the world (including countries in the African continent). The nature of Caribbean art reflects these diverse origins, as artists have taken their traditions and adapted these influences to reflect the reality of their lives in the Caribbean.

| Part of a series on: |

| Culture of the Caribbean |

|---|

|

| History |

|

| Topics |

|

Cultural diversity by region |

The governments of the Caribbean have at times played a central role in the development of Caribbean culture. However, some scholars and artists challenge this governmental role. Historically and in later times artists have combined British, French, Spanish, Dutch and African artistic traditions, at times embracing European styles and at other times working to promote nationalism by developing distinctly Caribbean styles. Caribbean art remains the combination of these various influences.

Early influences

The first immigrants (said to be originally from the Orinoco basin) to the Caribbean region were the Taíno (those found throughout much of the Greater and Lesser Antilles), and the Arawak (those found in South America and part of Trinidad). These early Caribbeans are supposed to have occupied the region since 2000BC. In Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles, the Taíno-Arawak art has been found in stone carvings, figurines (which are essentially curvilinear) and pottery dating from the period before European contact and are said to be as old as twenty-four hundred years. These few discovered artifacts, preserved in museum collections, have contributed new culturally hybrid art forms.[1]

Not until the 1950s and 1960s did a small number of Caribbean artists began to renew and in some cases re-invent indigenous art forms. Currently there are no indigenous artists practicing in any media in the Caribbean.

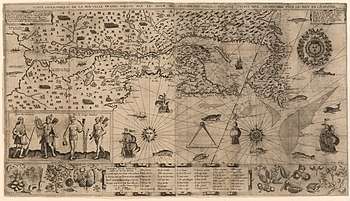

Art in the colonial period (from 1496)

The settlement in the Caribbean islands began by the Spanish on the island of Hispaniola as early as 1496. They then settled on Puerto Rico followed by Cuba. They did not colonise Trinidad until 1592. It is extremely unlikely that the Taíno-Arawak people had any input to the spaniade artistic developments since it has been estimated that their population was quickly depleted from 200,000 to as little as 500.

French settlers arrived in the Caribbean in the 1625 and established trading ports on the islands of St. Kitts, Tortuga (in 1628, now a British Virgin Island) in Saint-Domingue (later Haiti), Martinique, and Guadeloupe (both in 1635). Near the end of the 17th century, the population of the French Caribbean was growing steadily but the territory was increasingly isolated from France because in 1674 the French trading company finally failed, and few artists had arrived from Europe.[2] Currently little or no research has been done to highlight the early French influenced art forms originating in the Caribbean, nor to list artists who might fit within this category.

Although Trinidad was never governed by the French, the islands original settlers, the Spanish, allowed planters from the French islands to settle and develop the country from about 1777.[3] The effect of French occupation can be seen in the names of places and to a smaller extent in the laws of the country - so it is highly possible that art also may have early French influences.

According to Jamaican art historian Petrine Archer, "there is sparse evidence of local art production in any of the islands prior to the 20th century" other than from the occasional visiting European.[4] Haiti was a lone exception.

The Caribbean Artists Movement

A key movement that sprung from Caribbean Art was the Caribbean Artist Movement (Also known as CAM). The movement lasted for less than ten years while the founders of the movement were Eddie Brathwaite, John Larose, and Andrew Salkey.[5] In 1966, CAM resulted from the works of Caribbean Art: artists, writers, poets, filmmakers, actors, and musicians that made an excursion to London England.[6] The Caribbean Artist Movement was a new look into the arts that transferred ideas amongst Caribbean artists. This gave them a shared Caribbean ‘nationhood’ which in turn allowed people to take pride in their new cultural achievements. CAM held many newsletters, conferences, and exhibitions to showcase the Caribbean Arts; however, many of these events were held to get recognition of Caribbean artists.[7]

Contemporary trends in Caribbean art

Art made in the Caribbean by living Caribbean artists refers to a range of visual, media, performance, and other practices that are critically acclaimed. There has been much debate over whether a national style, philosophical outlook, or unified and cohesive culture exists or ever has existed within the Caribbean. Geographically it is large, with many distinct regions, and its population are diverse and made up of varying national and ethnic backgrounds. Also distinctions between "high art" and "popular" art seem to be becoming less clear, making the task of locating common characteristics of Caribbean art or culture increasingly difficult.

Tumelo Mosaka, curator at the Brooklyn Museum (NY) suggests:

"Today, consistent throughout most islands is the division between mainstream artist movements more closely related to European stylistic trends and often rooted in national development, and self-taught artists whose art works reflect ritual preoccupations related to spiritual movements such as Revivalism, Santería and Vodou and less exposure to art movements abroad. More recently, contemporary artists influenced by post-modernism's concerns with identity have found ways to fuse both forms resulting in art that appear peculiarly unique to their Caribbean experience".[8]

— Mosaka, T., Brooklyn Museum (NY)

Contemporary art in the Caribbean reflects an engagement with the region's cultural past. Archer describes recent trends as "a self-conscious and satirical embracing of cultural memory styled in unconventional settings, installations and off-the-wall works that straddle African traditions and European post-modern ideas of 'primitive' creativity." It is an imagery and history which is yet to be resolved.[4]

There are moments when contemporary artists living and working in the Caribbean — as individuals or groups — for example Christopher Cozier (Trinidad & Tobago), Deborah Anzinger (Jamaica), Humberto Diaz and Wilfredo Prieto (Cuba), Jorge Pineda / Quintapata (Dominican Republic), LaVaughn Bell (St. Croix), Maksaens Denis (Haiti), Tirzo Martha (Curacao) and Tony Cruz (Puerto Rico) to name a few have distinguished themselves through international recognition, collaboration, or "the spirit of the times".

See also

- ARC Magazine, a periodical dedicated to contemporary Caribbean art and culture

References

- JBMHS, . (1960–1965). "Arawak Art and Artifacts". Journal of Barbados Museum Historical Society. Barbados: Museum Historical Society. 27,30,32,36.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Newton, Arthur P. (1933). The European Nations in the West Indies, 1493–1688. London.

- Moron, G. (1964). A History of Venezuela. London: Allen and Unwin. p. 82.

- Archer, Petrine (1998). "Caribbean Art Archives". PetrineArcher.com. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Mitchell, Verner D., 1957- editor. Davis, Cynthia, 1946- editor. Encyclopedia of the Black Arts Movement. ISBN 978-1-5381-0146-9. OCLC 1078970560.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Caribbean Artists Movement (1966 - 1972)". The British Library. Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- Schwarz, Bill, editor. West Indian intellectuals in Britain. ISBN 978-1-84779-076-7. OCLC 990187434.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Mosaka (curator), Tumelo (17 Sep 2007). "Infinite Island (exh. cat.)". Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 10 Nov 2009.

Further reading

- Cummins, A., Thompson, A., Whittle, N., Art in Barbados, Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle Publishers (1999)