Siege of Cádiz

The Siege of Cádiz was a siege of the large Spanish naval base of Cádiz[6] by a French army from 5 February 1810 to 24 August 1812[7] during the Peninsular War. Following the occupation of Seville, Cádiz became the Spanish seat of power,[8] and was targeted by 70,000 French troops under the command of the Marshals Claude Victor and Nicolas Jean-de-Dieu Soult for one of the most important sieges of the war.[9] Defending the city were 2,000 Spanish troops who, as the siege progressed, received aid from 10,000 Spanish reinforcements as well as British and Portuguese troops.

During the siege, which lasted two and a half years, the Cortes of Cádiz – which served as a parliamentary Regency after Ferdinand VII was deposed – drew up a new constitution to reduce the strength of the monarchy, which was eventually revoked by Fernando VII when he returned.[10]

In October 1810 a mixed Anglo-Spanish relief force embarked on a disastrous landing at Fuengirola. A second relief attempt was made at Tarifa in 1811. However, despite defeating a detached French force of 15,000–20,000 under Marshal Victor at the Battle of Barrosa, the siege was not lifted.

In 1812 the Battle of Salamanca eventually forced the French troops to retreat from Andalusia, for fear of being cut off by the Coalition armies.[11] The French defeat contributed decisively to the liberation of Spain from French occupation, due to the survival of the Spanish government and the use of Cádiz as a jump-off point for the Coalition forces.[1]

Prelude

In the early 19th century, war was brewing between French emperor Napoleon and the Russian Tsar Alexander I, and Napoleon saw the shared interests of Britain and Russia in defeating him as a threat. Napoleon's advisor, the Duke of Cadore, recommended that the ports of Europe be closed to the British, stating that "Once in Cadiz, Sire, you will be in a position either to break or strengthen the bonds with Russia".[12]

Soult and his French army invaded Portugal in 1809 but were beaten by Wellesley at Oporto on 12 May. The British and Spanish armies advanced into mainland Spain, however the difficulties that the Spanish army bore forced Arthur Wellesley to retreat into Portugal after Spanish defeats in the battles of Ocaña and Alba de Tormes. By 1810 the war had reached a stalemate. Wellesley strengthened Portuguese and Spanish positions with the construction of the Lines of Torres Vedras, and the remainder of the Spanish forces fell back to defend the Spanish government at Cádiz against Soult's Army of Andalusia.

Siege

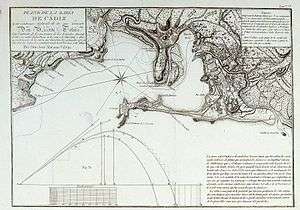

The port of Cádiz was surrounded on land by the armies of Soult and Victor, in three entrenched positions at Chiclana, Puerto Real and Santa Maria, positioned in a semicircle around the city.[13] In the case of the former position, only an area of marshland separated the forces.[14] The French initially sent an envoy with a demand for surrender, which was refused.[8] The fortress of Matagorda, north of Cádiz, was bombarded by the French. When the fort became untenable, it was evacuated by the defending 94th Regiment of Foot. The last person to leave was to be Maj Lefebure of the Royal Engineers, whose job was to fire a mine to destroy the fort, but he was killed by a cannon shot.[15] The French forces now had access to the coast close to Cádiz. The ensuing bombardment of the Spanish coastal city involved some of the largest artillery pieces in existence at the time, including Grand Mortars, which were so large they had to be abandoned when the French eventually retreated, and fired projectiles to distances previously thought impossible, some up to 5 kilometres (3 miles) in range.[5] (The Grand Mortar was placed in St. James's Park in London as a gift to the British in honour of the Duke of Wellington.[16]) The French continued to bombard Cádiz until the end of 1810, but the extreme distance lessened their effect.[17]

The terrain surrounding the strong fortifications of Cádiz proved difficult for the French to attack, and the French also suffered from a lack of supplies, particularly ammunition, and from continuous guerrilla raiding parties attacking the rear of their siege lines and their internal communications with Andalusia.[13] On many occasions, the French were forced to send escorts of 150–200 men to guard couriers and supply convoys in the hinterland. So great were the difficulties that one historian judges that:

The French siege of Cadiz was largely illusory. There was no real hope that they would ever take the place. Far more real was the siege of the French army in Andalusia. Spanish forces from the mountains of Murcia constantly harried the eastern part of the province. They were frequently defeated but always reformed. A ragged army under General Ballesteros usually operated within Andalusia itself. Soult repeatedly sent columns against it. It always escaped ... French dominion was secure only in the plains of the Guadalquivir and in Seville.[18]

French reinforcements continued to arrive through to 20 April, and the capture of an outer Spanish fort guarding the road through to the Puerto Real helped to facilitate the arrival of these forces. This captured fort also provided the French with a vantage point from which to shell ships coming in and out of the besieged Spanish port.[13]

During 1811 Victor's force was continually diminished by requests for reinforcement from Soult to aid his siege of Badajoz.[19] This reduction in men, which brought the French numbers down to between 20,000–15,000, encouraged the defenders of Cádiz to attempt a breakout.[20] A sortie of 4,000 Spanish troops, under the command of General José de Zayas, was arranged in conjunction with the arrival of an Anglo-Spanish relief army of around 16,000 troops that landed 80 kilometres (50 miles) south in Tarifa. This Anglo-Spanish force was under the overall command of Spanish General Manuel la Peña, with the British contingent being led by Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Graham. On 21 February 1811 the force set sail for Tarifa, and eventually landed at Algeciras on 23 February.[20] Eventually marching towards Cádiz on 28 February, the force met a detachment of two French divisions under Victor at Barrosa. The battle was a tactical victory for the Coalition force,[21] with a French regimental eagle captured,[22] but it was strategically indecisive.[23]

Smaller sorties of 2,000–3,000 men continued to operate out of Cádiz from April to August 1811.[24] On 26 October British naval gunboats from Gibraltar destroyed French positions at St. Mary's,[25] killing French artillery commander Alexandre-Antoine Hureau de Sénarmont. An attempt by Victor to crush the small Anglo-Spanish garrison at Tarifa over the winter of 1811–1812 was frustrated by torrential rains and an obstinate defence, marking an end to French operations against the city's outer works.

On 22 July 1812, Wellesley won a tactical victory over Auguste Marmont at Salamanca. The Spanish, British and Portuguese then entered Madrid on 6 August and advanced towards Burgos. Realising that his army was in danger of being cut off, Soult ordered a retreat from Cádiz set for 24 August. After an overnight artillery barrage, the French intentionally burst most of their 600 guns by overcharging and detonating them. The Coalition forces captured many guns, 30 gunboats and a large quantity of stores.[5]

In literature

- The siege of Cádiz features prominently in Bernard Cornwell's Sharpe's Fury, in which Richard Sharpe is forced to help defend the city from the French before going on to take part in the Battle of Barrosa.[26]

- Arturo Pérez-Reverte's El asedio is a murder mystery set in Cádiz during the siege.

See also

Notes

- Rasor 2004, p. 148.

- Payne 1973, p. 432.

- Clodfelter 2002, p. 174.

- Napier 1840, p. 100.

- Southey 1837b, p. 68.

- "The Spanish Ulcer: Napoleon, Britain, and the Siege of Cádiz". Humanities, January/February 2010, Volume 31/Number 1. Retrieved 2010-07-05.

- Fremont-Barnes 2002, p. 12–13.

- Russell 1818, p. 306.

- Fremont-Barnes 2002, p. 26.

- Noble 2007, p. 30.

- Napoleonic Guide Cadiz 5 February, 1810 – 24 August, 1812 retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Napoleonic Guides Franco-Russian Diplomacy, 1810–1812 retrieved 21 July 2007.

- Burke 1825, p. 169.

- Napier 1840, p. 169.

- Porter, Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers. London: Longmans. p. 270.

- St. James's Park, London Ancestor, retrieved July 21, 2007.

- Burke 1825, p. 170.

- Glover p. 120.

- Southey 1837, p. 165.

- Southey 1837, p. 167.

- Southey 1837, p. 179.

- History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Volume I by Maj Gen Porter |page=272

- Southey 1837, p. 180.

- Burke 1825, p. 172.

- Burke 1825, p. 174.

- Sharpe's Fury summary for the British Council. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

References

Printed Sources

- Burke, Edmund (1825), The Annual Register, for the year 1810 (2nd ed.), London, pp. 169–174

- Clay, Henry (1963), Papers of Henry Clay: Presidential Candidate, 1821–1824, University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 978-0-8131-0053-1

- Clodfelter, Michael (2002), Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500–2000, N.C.: Jefferson & London: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-1204-4

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory (2002), The Napoleonic Wars: The Peninsular War 1807–1814, Osprey Publishing ISBN 978-1-84176-370-5

- Napier, William Francis P. (1840), History of the war in the Peninsula, and in the south of France from 1807 to 1814

- Noble, John (2007), Andalucía, London: Lonely Planet, ISBN 978-1-74059-973-3

- Payne, Stanley G. (1973), A History of Spain and Portugal: Eighteenth Century to Franco. Volume 2. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press .

- Rasor, Eugene L. (2004), British Naval History to 1815: A Guide to the Literature, Westport, Conn.: Praeger, ISBN 978-0-313-30547-4

- Russell, William (1818), "Letter XVI: Progress of the War in various Scenes of Action", The History of Modern Europe:... with a continuation terminating at the pacification of Paris, 1815, 7, London, p. 306

- Southey, Robert (1837), History of the Peninsular War, V, J. Murray, pp. 167

- Southey, Robert (1837b), History of the Peninsular War, VI, J. Murray, pp. 68

Websites

- Napoleonic Guide Cádiz 5 February, 1810 – 24 August, 1812 retrieved July 21, 2007

- St. James's Park, London Ancestor, retrieved July 21, 2007

- www.guardiasalinera.com, The Siege of Cadiz Reenact (1810–2010).