Battle of Orthez

The Battle of Orthez (27 February 1814) saw the Anglo-Spanish-Portuguese Army under Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, Marquess of Wellington attack an Imperial French army led by Marshal Nicolas Soult in southern France. The outnumbered French repelled several Allied assaults on their right flank, but their center and left flank were overcome and Soult was compelled to retreat. At first the withdrawal was conducted in good order, but it eventually ended in a scramble for safety and many French soldiers became prisoners. The engagement occurred near the end of the Peninsular War.

| Battle of Orthez | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peninsular War | |||||||

The Final Charge of the British Cavalry at the Battle of Orthez, by Denis Dighton | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

36,000 48 guns |

44,000 54 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3,985 killed, wounded or captured 6 guns lost | 2,174 killed, wounded or captured | ||||||

In mid-February, Wellington's army broke out of its small area of conquered territory near Bayonne. Moving east, the Allies drove the French back from several river lines. After a pause in the campaign, the western-most Allied corps surrounded and isolated Bayonne. Resuming their eastward drive, the remaining two Allied corps pushed Soult's army back to Orthez where the French marshal offered battle. In subsequent operations, Soult decided to abandon the large western port of Bordeaux and fall back east toward Toulouse. The next action was the Battle of Toulouse.

Preliminaries

Armies

The Battle of the Nive ended on 13 December 1813 when Wellington's army repulsed the last of Soult's assaults. This ended the fighting for the year. Soult had found the Allied army divided by the Nive River but failed to inflict a damaging defeat. The French then pulled back within Bayonne's defenses and entered winter quarters.[1] Heavy rains brought operations to a standstill for the next two months. [2] After the Battle of Nivelle on 10 November 1813, Wellington's Spanish troops had gone out of control in seized French villages. Horrified at the idea of provoking a guerilla war by French civilians, the British commander imposed a vigorous discipline on his British and Portuguese soldiers and sent most of his Spanish troops home. Since his men were paid and fed by the British government, Pablo Morillo's Spanish division remained with the army.[3] Wellington's policy paid dividends; his soldiers soon found that guarding the roads in his army's rear areas was no longer required.[4]

In January 1814, Soult sent reinforcements to Napoleon. Transferred to the Campaign in Northeast France were the 7th and 9th Infantry Divisions and Anne-François-Charles Trelliard's dragoons.[5] Altogether, this totaled 11,015 foot soldiers under Jean François Leval and Pierre François Xavier Boyer and 3,420 horsemen in the brigades of Pierre Ismert, François Léon Ormancey and Louis Ernest Joseph Sparre.[6] This left Soult with the 1st Division under Maximilien Sébastien Foy (4,600 men), 2nd Division led by Jean Barthélemy Darmagnac (5,500 men), 3rd Division commanded by Louis Jean Nicolas Abbé (5,300), 4th Division directed by Eloi Charlemagne Taupin (5,600 men), 5th Division commanded by Jean-Pierre Maransin (5,000 men), 6th Division under Eugène-Casimir Villatte (5,200 men), 8th Division led by Jean Isidore Harispe (6,600 men) and Cavalry Division under Pierre Benoît Soult (3,800 men). Marshal Soult also commanded 7,300 gunners, engineers and wagon drivers plus the garrisons of Bayonne (8,800 men) and Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port (2,400 men).[7]

Wellington's army consisted of the 1st Division under Kenneth Howard (6,898 men),[8][9] 2nd Division commanded by William Stewart (7,780 men), 3rd Division led by Thomas Picton (6,626 men), 4th Division directed by Lowry Cole (5,952 men),[10] 5th Division under Andrew Hay (4,553 men),[9] 6th Division commanded by Henry Clinton (5,571 men), 7th Division led by George Townshend Walker (5,643 men), Light Division under Charles Alten (3,480 men), Portuguese Division directed by Carlos Lecor (4,465 men)[10] and Spanish Division led by Morillo (4,924 men).[11] Stapleton Cotton commanded three British light cavalry brigades under Henry Fane (765 men), Hussey Vivian (989 men) and Edward Somerset (1,619 men).[10] There were also three independent infantry brigades, 1,816 British led by Matthew Whitworth-Aylmer, 2,185 Portuguese under John Wilson[9] and 1,614 Portuguese directed by Thomas Bradford.[12]

Operations

Wellington planned to use the greater part of his army to drive the bulk of Soult's army well to the east, away from Bayonne. Once the French army was pressed sufficiently far to the east, a strong Allied corps would seize a bridgehead over the Adour River to the west of Bayonne and encircle that fortress. Because Soult's army was weakened by three divisions, Wellington's forces were superior enough to risk dividing them into two bodies.[13] Soult wished to contain his opponent in a wedge of occupied French territory. Strongly garrisoned Bayonne blocked the north side of the Allied-occupied area. East of the city, three French divisions held the line of the Adour to Port-de-Lanne. The east side of the Allied-occupied area was defended by four French divisions along the Joyeuse River as far south as Hélette. Cavalry patrols formed a cordon from there to the fortress of Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port in the Pyrenees.[4]

On 14 February, Wellington launched his offensive toward the east. On the right flank was Rowland Hill's 20,000-man corps which included the 2nd and 3rd Divisions, Lecor's Portuguese and Morillo's Spanish divisions and Fane's cavalry. Hill's main column struck toward Harispe's division at Hélette. Picton moved on the left flank against Villatte's division at Bonloc and Morillo took his men through the foothills on the right flank.[14] On 15 February, Hill's column defeated Harispe's division in the Battle of Garris and forced the French to abandon Saint-Palais and the line of the Bidouze River.[15]

The 25,400-strong Allied left flank corps under William Beresford began its advance on 16 February, aiming for the village of Bidache. Beresford's corps was made up of the 4th, 6th, 7th and Light Division as well as Somerset's and Vivian's cavalry. Altogether, Wellington had 42,000 foot soldiers and 3,000 horsemen marching to the east. Reacting to the Allied pressure, Soult joined two of the three divisions north of the Adour to the four divisions farther east. This action created a field army of 32,000 infantry and 3,800 cavalry. The French divisions were directed to form a new line behind the Gave d'Oloron River, along a line from Peyrehorade to Sauveterre-de-Béarn to Navarrenx.[15] On 17 February, Hill's corps forded the Saison River, breaching yet another French defensive line.[16] The French marshal sent Abbé's division to help defend Bayonne, a questionable move which left his army with fewer troops to fight Wellington. By 18 February, Soult had his troops in position on the Gave d'Oloron. That day the weather broke again, causing another pause in operations.[17]

During the lull, Wellington ordered John Hope's corps to begin the isolation of Bayonne. Since Adour is 300 yards (274 m) wide with a tidal rise of 14 feet (4.3 m) below Bayonne, Soult never suspected the Allies would cross there and did not guard the north bank. Facing an Allied offensive that required crossing rivers, the French marshal believed that his foes would not have enough boats or pontoons to bridge the river.[17] Hope sent eight companies from the 1st Division across the Adour on 23 February to form a bridgehead. That evening Congreve rockets dispersed two French battalions that were sent to investigate the incursion. The next day 34 vessels of 30 to 50 tons sailed into the mouth of the Adour, were moored together and a roadway was built across their decks.[18] By the evening of 26 February, Hope marched 15,000 of his 31,000 men over the bridge onto the north bank. After sustaining 400 casualties in a successful bid to capture the Sainte-Étienne suburb, the Allies encircled Bayonne on 27 February. French casualties were only 200 in the action.[19] The siege was pursued in a lackadaisical fashion until 14 April when the bloody and pointless Battle of Bayonne erupted.[20]

On 24 February, Wellington launched a new offensive against Soult's army. For this operation, Hill was reinforced by the 6th and Light Divisions. Beresford with two divisions mounted a feint attack against the northern end of the French line. Picton was supposed to demonstrate opposite Sauveterre but he exceeded his orders.[21] He found an apparently unguarded ford about 1,000 yards (914 m) from the bridge and pushed four light companies from John Keane's brigade across. After a steep climb, they reached high ground only to be overpowered by a battalion of the 119th Line Infantry from Villatte's division. In their flight down the slope and across the river, about 30 men were captured and a few drowned; about 80 of the 250 men became casualties.[22] Hill built a boat bridge and thrust 20,000 troops across the Gave d'Oloron at Viellenave-de-Navarrenx between Sauveterre and Navarrenx.[19] With his latest position compromised, Soult ordered a retreat to Orthez on the Gave de Pau River.[21]

Battle

Plans and forces

Since Wellington was anxious not to bring on an engagement, he tried to flank Soult out of position. He sent Beresford to cross the Gave de Pau downstream at Lahontan and circle around Soult's right flank. At the same time, Hill's corps moved directly toward Orthez. By 25 February, Soult had massed his army at Orthez and courted battle with the Allies.[23] The French marshal counted 33,000 foot soldiers, 2,000 horsemen, 1,500 gunners and sappers, supported by 48 field guns.[24] Wellington could bring 38,000 infantry, 3,300 cavalry, 1,500 gunners and sappers, supported by 54 artillery pieces against the French. Five battalions were absent: 1/43rd Foot and 1/95th Rifles from the Light Division, 2nd Provisional from 4th Division, 79th Foot from 6th Division and 51st Foot from 7th Division.[25] Confronted with Soult in a fighting mood, the British commander planned to send Beresford to break Soult's right flank while Picton and three divisions kept the French center busy. Meanwhile, Hill's corps was to attack Orthez, get across the Gave de Pau and envelop the French left flank. With luck, Soult would be crushed between Beresford and Hill.[23]

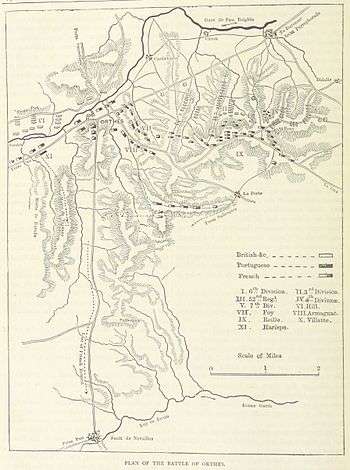

At Orthez, the Gave de Pau runs approximately from southeast to northwest. Since Beresford was already on the same side of the Gave de Pau, the river only protected Soult's position to the east of Orthez. However, there is an east-west ridge on the north side of Orthez that ends at the village of Saint-Boès on the west.[26] The ridge is about 500 feet (152 m) high and the road from Orthez to Dax runs along its crest. However, the knolls at the Lafaurie, Luc and Plassotte Farms were even higher, the last-named rose 595 feet (181 m) above Saint-Boès. The three high points were crowned with French artillery. Aside from Saint-Boès, the ridge can be approached from the west by two spurs with marshy ground in between.[27]

Soult posted four and one-half divisions along this ridge, one division in Orthez and one division in reserve. Unlike the other divisions which had two brigades, Harispe's division contained three brigades. His third brigade under Marie Auguste Paris was detached to the right flank. Going from right to left, the ridge was held by the divisions of Taupin, Claude Pierre Rouget, Darmagnac and Foy. Rouget was in temporary command of Maransin's division. Harispe's remaining two brigades held Orthez while Villatte's division was in reserve north of Orthez.[26] Honoré Charles Reille commanded Taupin, Rouget and Paris on the right flank, Jean Baptiste Drouet, comte d'Erlon led Darmagnac and Foy in the center and Bertrand Clausel supervised Harispe and Villatte on the left flank.[28][29] Pierre Soult's cavalry was scattered. The 2nd Hussars and the 22nd Chasseurs-à-Cheval were near Pau and out of the battle. The 13th, 15th and 21st Chasseurs-à-Cheval were detached to Harispe, D'Erlon and Reille, respectively, while the 5th and 10th Chasseurs-à-Cheval were in reserve.[30]

Wellington planned to send Cole's 4th Division supported by Walker's 7th Division to attack the western end of the ridge under the direction of Beresford. Picton would lead his own 3rd Division and Clinton's 6th Division in pinning the French center. Hill's corps was ordered to feint against Orthez with a Portuguese brigade and hold his two divisions ready to cross the Gave de Pau to the east of Orthez.[26] Alten's Light Division was placed under cover behind an old Roman camp where Wellington set up his headquarters. The camp was located between Beresford's and Picton's columns.[25] The 44,402-strong Allied army included 3,373 light cavalry in three brigades and 1,512 gunners, engineers and wagon drivers.[31] Morillo's division was besieging Navarrenx while five British battalions were not present in the field while being issued fresh uniforms.[21] The 1st Hussars King's German Legion (KGL) Regiment was part of the Allied cavalry.[15]

Action

The morning of 27 February 1814 saw a light frost, but the ground was not frozen. At 8:30 a.m. the 4th Division assaulted Taupin's soldiers at Saint-Boès.[32] The initial rush seized the church which stood on a separate hill. The brigade of Robert Ross swept through Saint-Boès but was repulsed by the battery on the Plassotte knoll. When his soldiers fell back into the village, Cole brought up a KGL battery to duel with Taupin's guns. The battery immediately became the target of the French batteries on the Plassotte and Luc knolls; two guns were knocked out[33] and Captain Frederick Sympher was killed.[34] Cole deployed José Vasconcellos' Portuguese brigade on Ross' right and sent his line forward again. The result was a second repulse in which Ross went down with a wound. The subsequent counterattack by Taupin's troops recovered part of Saint-Boès.[33] For a time there was a lull as the two sides fired away at each other from the houses, but Vasconcellos' men had no cover and began to edge backward. Wellington sent over the 1st Caçadores Battalion from the Light Division. Cole's line collapsed just as the reinforcement arrived. Taupin recovered the entire village and drove the Allies back to their starting point.[35] Ross' brigade suffered 279 casualties and Vasconcellos' brigade lost 295.[36]

Picton's probing attacks against the French center also met stiff resistance.[23] Picton split the 3rd Division, sending Thomas Brisbane's brigade up the right spur toward Foy's position and Keane's brigade up the left spur toward Darmagnac's division. Keane was supported by Manley Power's Portuguese brigade from 3rd Division. Brisbane was followed up the right spur by Clinton's 6th Division. Since the valleys between the spurs were deep and muddy, both advances were restricted to narrow fronts.[35] Picton's skirmishers quickly drove back the French outposts. When the leading brigades came under accurate artillery fire from the Escorial and Lafaurie knolls, Picton held back his formed troops and reinforced his skirmish line to seven British light companies, three 5th/60th Foot rifle companies and the entire 11th Caçadores Battalion. This heavy skirmish line moved forward until it came into contact with Soult's main defense line, but it was unable to press any farther. For two hours, Picton waited for Beresford's attack to make progress as the two sides skirmished.[37]

Wellington quickly changed his plans after seeing his flank attack fail. He converted his holding attack with the 3rd and 6th Divisions into a head on assault.[32] The new assault began around 11:30 am. The British commander sent every available unit against the French right flank and center. He held back only 2/95th Foot and 3/95th Foot, the Portuguese 3rd Caçadores Battalion and the 17th Line Infantry Regiment from the Light Division. The brigades of Ross and Vasconcellos were withdrawn and replaced by the 7th Division.[37] The struggle for Saint-Boès broke out anew when Walker's division and William Anson's brigade of 4th Division attacked, supported by two British artillery batteries firing from the church knoll. Four battalions attacked in the center led by the 6th Foot. Two battalions were deployed to the left and John Milley Doyle's Portuguese brigade was on the right.[38] Taupin's tired soldiers, who had been fighting for about four hours, were driven back behind the Plassotte knoll where they rallied.[39]

When it advanced, Brisbane's brigade came under artillery fire that caused many casualties. The brigade finally reached some dead ground where the guns could not hit them, but French skirmishers began picking off the soldiers. After some urging by Edward Pakenham, Brisbane continued the attack. The 1/45th Foot fought its way close to the top of the ridge where Joseph François Fririon's brigade of Foy's division held the ridgeline.[40] On the left of Brisbane's brigade, the 1/88th Foot had two companies guarding the divisional artillery battery as it began pounding the French line. Soult spotted the threat and ordered a squadron of the 21st Chasseurs-à-Cheval to charge. The cavalry overran the two companies, inflicting heavy losses, and then went after the gunners. The remaining companies of the 88th immediately opened fire on the French horsemen, mowing most of them down.[41] The 21st Chasseurs went into combat 401 strong but 11 days later reported only 236 men on active duty.[42] The 88th Foot suffered 269 killed and wounded, by far the most of any British unit.[36]

While Foy walked behind his front line units, a shrapnel shell burst over his head, driving a bullet into his left shoulder. His wounding disheartened his soldiers, who began falling back.[42] At about the same time, Brisbane's brigade was replaced in the front line by two brigades of Clinton's 6th Division. These fresh troops fired a volley from close range and advanced with the bayonet, driving the French down the ridge's rear slope.[41] Pierre André Hercule Berlier's brigade of Foy's division, which was closer to Orthez, fell back after Fririon's retreat exposed its flank.[42] With Berlier gone, Harispe's two battalions in Orthez were compelled to retreat in order to avoid capture. On the left spur, Picton's two brigades under Keane and Power pressed against Darmagnac's division. After Foy's division gave way, Darmagnac retreated to the next ridge in the rear, where his troops took position on the right of Villatte's division. The divisional batteries of Picton and Clinton zeroed in on the new French position.[43]

Rouget's division and Paris' brigade apparently began to pull back after Darmagnac's retreat. Seeing a gap open between Rouget and Taupin, Wellington ordered the 52nd Foot to advance from the Roman Camp and drive a wedge into the French defensive line. The unit's commander John Colborne led his men across some marshy ground and then up the slope toward the Luc knoll, followed by Wellington and his staff. They won a foothold at the top of the ridge on Taupin's left flank.[44] With both its flanks turned, Taupin's division hurriedly retreated to the northeast, the last French unit to be dislodged. The mauled division never rallied, though it managed to save all but two of its cannons. At some position to the rear, Rouget's division and Paris' brigade joined together and fought a hard battle against the pursuing Allies.[45]

John Buchan's brigade skirmished with the French defenders of Orthez all morning. Having received orders to cross the Gave de Pau, Hill got his troops marching for the Souars Ford at 11:00 am. Arriving there, the 12,000 Anglo-Portuguese brushed aside the cavalry regiment and two battalions of the 115th Line Infantry Regiment defending the ford. Hill's troops were soon across the river in strength and pressing back Harispe's outnumbered division. They were joined by Buchan's Portuguese who crossed at the Orthez bridge the moment the town's defenders pulled out.[46] Joined by some newly arrived conscript battalions, Harispe attempted to make a stand at the Motte de Tury heights. The raw recruits proved to be poor fighting material; Hill's men broke Harispe's line and captured three guns.[47]

Wellington's Spanish liaison officer, Miguel Ricardo de Álava y Esquivel, was hit by a spent bullet during the advance. As Wellington was teasing Álava, he was knocked off his horse when a bullet-sized canister shot struck his sword hilt. In pain from a badly bruised hip, the British army commander remounted and continued to direct the battle.[32] At this time, Soult realized that Hill's column might cut off his army from the Orthez to Sault-de-Navailles road. He ordered his army to retreat, covered by Villatte, Darmagnac, Rouget and Paris. At first, the tricky withdrawal was conducted in good order, though it was closely followed by British horse artillery and infantry. Because they had to retreat on narrow paths and across country, the retreating French units became badly mixed and unit cohesion was lost. Fearful of capture, the retreating soldiers became more and more confused and demoralized.[47]

Villatte and Harispe covered the withdrawal.[48] At Sallespisse the troops from the French right and center poured into the main road. Soldiers from Villatte's division held that village until expelled by the 42nd Foot (Black Watch) in a hard fight. For the final 3 miles (5 km) to the Sault-de-Navailles bridge, most of Soult's army was a mob. That the cavalry brigades of Fane, Vivian and Somerset did not wreak havoc on the French was due to the terrain, which was criss-crossed with walls and ditches. Only the 7th Hussars made an effective charge, riding down one battalion of the 115th Line and a French National Guard unit from Harispe's division. At Sault-de-Navailles, Soult's artillery chief Louis Tirlet set up a 12-gun battery to cover the bridge over the Luy de Béarn.[49] Soult's beaten men flowed across the bridge and kept going until they reached Hagetmau. Villatte and Harispe's infantry and Pierre Soult's cavalry stayed in Sault-de-Navailles until 10:00 pm when they blew up the bridge and joined the retreat.[50]

Results

The French lost the battle on French soil as Soult lost six field guns and 3,985 men including 542 killed, 2,077 wounded and 1,366 prisoners. Foy and brigadiers Étienne de Barbot and Nicolas Gruardet were wounded.[10] General of Brigade Jean-Pierre Béchaud of Taupin's division was killed.[51] The Allies sustained losses of 367 killed, 1,727 wounded and 80 captured for a total of 2,174. Of these, Portuguese casualties numbered 156 killed, 354 wounded and 19 captured,[52] while British losses were 211 killed, 1,373 wounded and 61 captured.[53] In addition to battle casualties, many of the recently conscripted French soldiers promptly deserted. Soult did not attempt to defend the Luy de Béarn with his demoralized army. Instead he retreated north to Saint-Sever on the Adour.[54]

Soult was in a dilemma. He could not defend both the important southwestern port of Bordeaux and Toulouse. He decided that trying to hold Bordeaux would put the Garonne Estuary at his back and that it would be difficult to obtain food in that area. Therefore, the French marshal determined to operate to the east in the direction of Toulouse.[54] On 2 March, the Allies clashed with the French at Aire-sur-l'Adour in a combat that cost the French about 250 men killed and wounded, including 12 officers, and 100 captured. Hippolita Da Costa sent his Portuguese brigade to attack a strong position. When it was repulsed with losses of five officers and 100 men, Da Costa failed to rally the soldiers and was replaced in command. British losses were 156 killed and wounded in the 2nd Division.[55] After this action with Hill, Harispe abandoned Aire.[48] Soult withdrew to a position between Maubourguet and Plaisance where his army was left alone for ten days.[56]

Wishing to capitalize on Soult's failure to defend Bordeaux, Wellington sent Beresford and the 4th and 7th Divisions to seize the seaport.[54] Beresford departed the Allied camp on 7 March and occupied Bordeaux on 12 March.[57] Leaving the 7th Division as an occupation force, Beresford hurried back with the 4th Division to join Wellington on 19 March. During this period, Allied infantry strength fell to 29,000 which was why Wellington did not trouble Soult.[56] To make up for the deficit, the British army commander called for his heavy cavalry brigades to join him. He also asked for 8,000 Spanish reinforcements to be forwarded to the army, the soldiers to be paid by the British treasury.[54] The Battle of Toulouse would be fought on 10 April.[58]

Notes

- Gates 2002, pp. 447–449.

- Glover 2001, p. 311.

- Glover 2001, p. 293.

- Glover 2001, p. 312.

- Glover 2001, p. 394.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 568.

- Glover 2001, pp. 393–394.

- Smith 1998, p. 477.

- Glover 2001, p. 385.

- Smith 1998, p. 501.

- Glover 2001, p. 387.

- Glover 2001, p. 386.

- Oman 1997, p. 318.

- Glover 2001, p. 313.

- Glover 2001, p. 314.

- Gates 2002, p. 452.

- Glover 2001, p. 315.

- Glover 2001, pp. 316–317.

- Gates 2002, p. 454.

- Smith 1998, p. 524.

- Glover 2001, p. 320.

- Oman 1997, p. 344.

- Gates 2002, p. 455.

- Oman 1997, p. 355.

- Oman 1997, p. 357.

- Glover 2001, pp. 320–321.

- Oman 1997, p. 352.

- Smith 1998, p. 500.

- Gates 2002, pp. 528–529.

- Oman 1997, pp. 354–355.

- Gates 2002, p. 528.

- Glover 2001, p. 322.

- Oman 1997, p. 358.

- Hall 1998, p. 548.

- Oman 1997, p. 359.

- Oman 1997, pp. 553–554.

- Oman 1997, p. 360.

- Oman 1997, p. 365.

- Oman 1997, p. 366.

- Oman 1998, p. 361.

- Oman 1997, p. 362.

- Oman 1997, p. 363.

- Oman 1997, p. 364.

- Oman 1997, pp. 366–367.

- Oman 1997, p. 368.

- Oman 1997, p. 369.

- Oman 1997, p. 370.

- Gates 2002, p. 457.

- Oman 1997, p. 371.

- Oman 1997, p. 372.

- Oman 1997, p. 373.

- Smith 1998, p. 504.

- Smith 1998, p. 503.

- Glover 2001, p. 323.

- Smith 1998, pp. 505–506.

- Glover 2001, p. 324.

- Gates 2002, p. 458.

- Smith 1998, p. 518.

References

- Gates, David (2002). The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-9730-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glover, Michael (2001). The Peninsular War 1807–1814. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-139041-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, John A. (1998). A History of the Peninsular War Volume VIII: The Biographical Dictionary of British Officers Killed and Wounded, 1808–1814. 8. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole. ISBN 1-85367-315-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nafziger, George (2015). The End of Empire: Napoleon's 1814 Campaign. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-96-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oman, Charles (1997) [1930]. A History of the Peninsular War Volume VII. 7. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole. ISBN 1-85367-227-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Broughton, Tony (2010). "Generals Who Served in the French Army during the Period 1789–1815". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 30 December 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) This is an excellent source for the full names of French generals.

- Chandler, David (1979). Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-523670-9.

- Rozes, Stéphane. "Bataille d'Orthez: 27 Février 1814".