Battle of Alba de Tormes

In the Battle of Alba de Tormes on 26 November 1809, an Imperial French corps commanded by François Étienne de Kellermann attacked a Spanish army led by Diego de Cañas y Portocarrero, Duke del Parque. Finding the Spanish army in the midst of crossing the Tormes River, Kellermann did not wait for his infantry under Jean Gabriel Marchand to arrive, but led the French cavalry in a series of charges that routed the Spanish units on the near bank with heavy losses. Del Parque's army was forced to take refuge in the mountains that winter. Alba de Tormes is 21 kilometres (13 mi) southeast of Salamanca, Spain. The action occurred during the Peninsular War, part of the Napoleonic Wars.

| Battle of Alba de Tormes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Peninsular War | |||||||

View of Alba from across the river Tormes | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 16,000, 12 guns | 32,000, 18 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 300 to 600 | 3,000, 9 guns | ||||||

The Spanish Supreme Central and Governing Junta of the Kingdom planned to launch a two-pronged attack on Madrid in the fall of 1809. In the west, Del Parque's Army of the Left enjoyed some success against Marchand's weak VI Corps. When the Spanish general learned that the other offensive prong had been crushed at Ocaña, he turned around and began retreating rapidly to the south. At the same time, Marchand was reinforced by a dragoon division under Kellermann. Taking command, Kellermann raced in pursuit of the Army of the Left, catching up with it at Alba de Tormes. Not waiting for their own foot soldiers, the French dragoons and light cavalry fell upon the Spanish infantry and defeated it. Marchand's infantry arrived in time to mop up, but the cavalry had done most of the fighting. Del Parque's men retreated into the mountains where they spent a miserable few months.

Background

By the summer of 1809, the Spanish Supreme Central and Governing Junta of the Kingdom was coming under harsh criticism over its handling of the war effort. The Spanish people demanded that the ancient Cortes be summoned and the Junta reluctantly agreed. But it was difficult to restore the old assembly and bring it into session. Ultimately, the Cortes of Cádiz would be set up, but until that day arrived the Junta exercised power. Anxious to justify its continued existence, the Junta came up with what it hoped would be a war-winning strategy.[1]

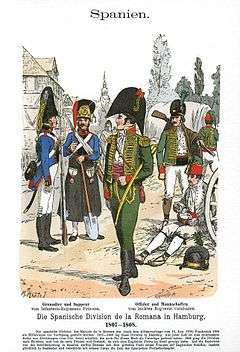

Undeterred by the fact that Arthur Wellesley, Viscount Wellington refused to contribute any British soldiers, the Junta planned to launch a two-pronged offensive aimed at recapturing Madrid. They replaced Pedro Caro, 3rd Marquis of la Romana with Diego de Cañas y Portocarrero, Duke del Parque as commander of the troops in Galicia and Asturias. Del Parque soon massed 30,000 troops at Ciudad Rodrigo with more on the way. South of Madrid, Juan Carlos de Aréizaga assembled over 50,000 well-equipped men in the Army of La Mancha. The main efforts of Del Parque and Aréizaga would be aided by a third force that operated near Talavera de la Reina under José Miguel de la Cueva y de la Cerda, Duke of Albuquerque. The 10,000-man Talavera force was designed to hold some French units in place while the main armies thrust at Madrid.[2]

In the fall of 1809, Del Parque's Army of the Left numbered 52,192 men in one cavalry and six infantry divisions. Martin de la Carrera's Vanguard Division counted 7,413 soldiers, Francisco Xavier Losada's 1st Division had 8,336 troops, Conde de Belveder's 2nd Division was made up of 6,759 men, Francisco Ballesteros's 3rd Division numbered 9,991 soldiers, Nicolás de Mahy's 4th Division comprised 7,100 troops, and Conde de Castrofuerte's 5th Division counted 6,157 men. All infantry divisions included 14 battalions except the 3rd with 15 and the 5th with seven. The Prince of Anglona's Cavalry Division included 1,682 horsemen in six regiments. Ciudad Rodrigo was provided with a garrison of 3,817 troops and there was an unattached 937-man battalion.[3]

With Marshal Michel Ney on leave, Jean Gabriel Marchand assumed command of the VI Corps, based at Salamanca. The corps had been forced to quit Galicia earlier in 1809 and had been involved in the operations in the aftermath of the Battle of Talavera in July. After hard campaigning and a lack of reinforcements, VI Corps was not in a good condition to fight. Furthermore, Marchand's talents were not equal to those of his absent chief. Del Parque advanced from Ciudad Rodrigo in late September[4] with the divisions of La Carrera, Losada, Belveder, and Anglona. Filled with scorn for his Spanish adversaries, an overconfident Marchand advanced on the village of Tamames, 56 kilometres (35 mi) southwest of Salamanca. In the Battle of Tamames on 18 October 1809, the French suffered an embarrassing defeat.[5] The French lost 1,400 killed and wounded out of 14,000 soldiers and 14 guns. Spanish casualties were only 700 out of 21,500 men and 18 cannons. After the battle, Del Parque was joined by Ballesteros' division, giving him 30,000 troops. As the Spanish advanced, Marchand abandoned Salamanca and Del Parque's men occupied the city on 25 October.[6]

Marchand retreated north to the town of Toro on the Duero River. Here he was joined by François Étienne de Kellermann with 1,500 infantry in three battalions and a 3,000-trooper dragoon division. Kellermann took command of the French force and marched upstream, crossing to the south bank at Tordesillas. Reinforced by General of Brigade Nicolas Godinot's force, Kellermann challenged Del Parque by marching directly on Salamanca. The Spaniard backpedaled, giving up Salamanca and retreating to the south. In the meantime, the guerillas in Province of León became very active. Kellermann left the VI Corps holding Salamanca and raced back to León to stamp out the uprising.[7]

Albuquerque managed to pin down some French troops near Talavera as planned, but when he found out that Aréizaga's army had been cut to pieces at the Battle of Ocaña on 19 November, he wisely withdrew out of reach of the French. Meanwhile, Del Parque heard of the march of Godinot's and General of Brigade Pierre-Louis Binet de Marcognet's brigades toward Madrid. Though he had been instructed to join Albuquerque, he instead moved on Salamanca again, hustling one of the VI Corps brigades out of Alba de Tormes.[8] Del Parque occupied Salamanca on 20 November.[9] The French general withdrew behind the Duero and again rendezvoused with Kellermann. Hoping to get between Kellermann and Madrid, Del Parque thrust toward Medina del Campo. On 23 November at that town, Marcognet's brigade returned from Segovia while General of Brigade Mathieu Delabassée's brigade arrived from Tordesillas. At this moment, Del Parque's columns hove into view and there was a skirmish at El Carpio. The French horsemen initially drove back the Spanish cavalry but were repulsed by Ballesteros' steady foot soldiers fighting in squares. This event prompted Marcognet and Delabassée to retreat.[10]

On 24 November, Kellermann massed 16,000 French troops on the Duero near Valdestillas. Badly outnumbered, the French prepared to defend themselves. But on this day the Army of the Left received news of the Ocaña disaster.[11] Understanding that this dire event meant that the French could spare plenty of soldiers to track down his army, Del Parque bolted to the south, intending to shelter in the mountains of central Spain.[12] On 25 November, Del Parque slipped away so suddenly that Kellermann did not even begin his pursuit until the next day. For two days, the French were unable to catch up with their adversaries. But on the afternoon of 28 November, their light cavalry found the Army of the Left camped at Alba de Tormes.[11]

Battle

Believing that he was out of Kellermann's reach, Del Parque grew careless. He allowed his army to camp in a bad position astride the Tormes River. The divisions of Ballesteros and Castrofuerte bivouacked on the east bank while the divisions of Anglona, La Carrera, Losada, and Belveder were in the town and on the west bank. Since the cavalry pickets were posted too close the camp, they did not give adequate warning of the arrival of the French. Riding with his light cavalry advance guard, Kellermann determined to attack at once. He feared that if he waited for Marchand's infantry, the Spanish would have time to establish a defensive line behind the Tormes. The decision meant that unsupported French cavalry would be attacking a much larger force of Spanish cavalry, infantry, and artillery.[11]

The reinforced VI Corps included Marchand's 1st Division, General of Division Maurice Mathieu's 2nd Division, General of Brigade Jean Baptiste Lorcet's light cavalry brigade, and Kellermann's dragoon division. The 1st Division included three battalions each of 6th Light Infantry Regiment, and the 39th, 69th and 76th Line Infantry Regiments. The 2nd Division counted three battalions each of 25th Light, 27th Line, and 59th Line, plus one battalion of the 50th Line. Lorcet's corps cavalry comprised four squadrons each of the 3rd Hussar and 15th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiments. The dragoon division was made up of the 3rd, 6th, 10th, 11th, 15th, and 25th Dragoon Regiments. Kellerman had no more than 3,000 cavalry and 12 guns immediately available.[13][14]

La Carrera's division consisted of three battalions each of the Principe and Zaragosa Line Infantry Regiments, one battalion each of the Barbastro, 1st Catalonia, 2nd Catalonia, and Gerona Light Infantry Regiments, one battalion each of the Vitoria, Escolares de Leon, Monforte de Lemos, and Muerte Volunteer Regiments, and one foot artillery battery. Losada's division included two battalions each of the Leon and Voluntarios de Corona Line Infantry and Galicia Provincial Grenadier Militia, one battalion each of the 1st Aragon and 2nd Aragon Light Infantry, two battalions of the Betanzos Volunteer Regiment, one battalion each of the Del General, 1st La Union, 2nd La Union, and Orense Volunteer Regiments, one company of National Guards, and one foot artillery battery.[9][15][16]

Belveder's division comprised the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the Rey, Seville, Toledo, and Zamora Line Infantry, two battalions each of the foreign Hibernia Line and Lovera Volunteer Regiments, one battalion each of the Voluntaros de Navarre Light Infantry, and Santiago Volunteer Regiments, and one foot artillery battery. Anglona's division had the regular 2nd Reyna (Cavalry or Dragoon), 5th Borbon Cavalry, 6th Sagunto Dragoon, and Provisional Regiments, the volunteer Llerena Horse Grenadiers and Ciudad Rodrigo Cazadores, and one horse artillery battery.[15]

Ballesteros' division consisted of three battalions of the Navarra Line Infantry and two battalions of the Princesa Line Infantry Regiments, one battalion each of the Oviedo Militia and the Candas y Luanco, Cangas de Tineo, Castropol, Covadonga, Grado, Infiesto, Lena, Pravia, and Villaviciosa Volunteer Regiments, and one foot artillery battery. Castrofuertes' division was made up of one battalion each of the Tiradores de Ciudad Rodrigo, 2nd Ciudad Rodrigo, and Ferdinand VII Volunteer Regiments, and Leon, Lagroño, Toro, and Valladolid Militia, and one artillery battery. One battalion formed Del Parque's headquarters guard. Mahy's 4th Division was detached from the army at the time of the battle.[15]

The Spanish divisions on the east bank hastily formed front against the French, with La Carrera's division holding the left flank, Belveder's the center, and Losada's the right flank. The 1,200 sabers belonging to the Prince of Anglona covered the entire front. To face the threat, Del Parque put as few as 18,000 men[17] or as many as 21,300 infantry, 1,500 cavalry and 18 artillery pieces in line.[9]

Kellermann quickly formed his eight regiments in four lines, with Lorcet's two light cavalry regiments in the first line and the six dragoon regiments in the three supporting lines. Storming forward, the 3,000 horsemen burst through Anglona's cavalry and crashed into the Spanish right-center. The attack broke up all of Losada's and part of Belveder's formations. About 2,000 Spaniards threw down their muskets and surrendered, the rest fled across the bridge. The French also seized a battery of artillery. Del Parque was unable to bring up his other two divisions because the span was packed with panicked soldiers. Instead, he deployed them along the river to cover the retreat of the others.[17]

During the crisis, the men in La Carrera's and part of Belveder's divisions were able to form into brigade squares. Kellermann organized a second attack against the unbroken squares but the Spanish soldiers held steady and repelled the French cavalry. Since his infantry were still far in the rear, Kellermann tried to fix the enemy squares in place by launching partial charges. For two and a half hours, this tactic succeeded in pinning down the Spanish soldiers on the west bank. Marchand's infantry and artillery finally appeared on the horizon. Realizing that his men would be annihilated by a combined arms attack, La Carrera ordered an immediate retreat. The French cavalry rushed forward and inflicted further losses, but most of the Spanish troops got away over the bridge in the fading light. Marchand's leading brigade cleared some of Losada's rallied men out of the town of Alba and captured two more artillery pieces.[17]

Results

Del Parque ordered his army to retreat under cover of darkness. During the operation, a group of panicky horsemen caused a stampede in the marching columns and the three divisions that fought were badly scattered while other soldiers deserted.[18] The Spanish suffered 3,000 killed, wounded, and captured, plus nine cannon, five colors, and most of their baggage train. The French suffered between 300 and 600 killed or wounded in the action, including General of Brigade Jean-Auguste Carrié de Boissy wounded.[9]

Del Parque established his winter headquarters at San Martín de Trevejo in the Sierra de Gata and began reassembling his troops. He had led 32,000 men at Alba de Tormes, but a month later could only gather 26,000 soldiers. This suggests that 3,000 men deserted the colors after the battle. Worse was to follow. In the desolate district where the army was quartered, the starving troops were sometimes forced to subsist on acorns. By mid-January, 9,000 died or were rendered unfit by hunger and illness.[18]

The Arthur Wellesley, Marquess of Wellington wrote in disgust,

I declare that if they had preserved their two armies, or even one of them, the cause was safe. But no! Nothing will answer excepting to fight great battles in plains, in which their defeat is as certain as the commencement of the battle".[19]

The repercussions of the Ocaña and Alba de Tormes defeats were disastrous for the Spanish cause. With the Spanish armies severely weakened, Andalusia was exposed to French invasion. Wellington, who as late as 14 November was optimistic, now became anxious that the French might invade Portugal.[20]

References

- Gates, David (2002). The Spanish Ulcer: A History of the Peninsular War. London: Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-9730-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Glover, Michael (2001). The Peninsular War 1807–1814. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-141-39041-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oman, Charles (1996). A History of the Peninsular War Volume III. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole. ISBN 1-85367-223-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pivka, Otto von (1979). Armies of the Napoleonic Era. New York, NY: Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-5471-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

Footnotes

- Gates 2002, p. 194.

- Gates 2002, pp. 194–196.

- Gates 2002, p. 494.

- Gates 2002, p. 196.

- Smith 1998, pp. 333–334. This source also listed Ballesteros' division in the Spanish order of battle.

- Gates 2002, pp. 197–199.

- Gates 2002, p. 199.

- Oman 1996, p. 97.

- Smith 1998, p. 336.

- Oman 1996, p. 98.

- Oman 1996, p. 99.

- Gates 2002, p. 204.

- Smith 1998, p. 336. This authority omitted the 6th and 11th Dragoons, listed Lorcet as leading only the 3rd Hussars and 15th Chasseurs, and stated that the other four dragoon regiments were part of Kellermann's division.

- Oman 1996, pp. 535, 538. This source listed Kellermann's division as consisting of the 3rd, 6th, 10th, and 11th Dragoons, and the 15th and 25th Dragoons as part of Lorcet's command.

- Oman 1996, p. 527.

- Pivka 1979, pp. 239–242. This source identified which regular units were line or light infantry, or heavy cavalry or dragoons.

- Oman 1996, p. 100.

- Oman 1996, p. 101.

- Glover 2001, p. 116.

- Gates 2002, pp. 205–206.