Charles Joseph Bonaparte

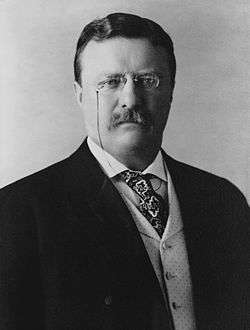

Charles Joseph Bonaparte (/ˈboʊnəpɑːrt/; June 9, 1851 – June 28, 1921) was an American lawyer and political activist for progressive and liberal causes. Originally from Baltimore, Maryland, he served in the cabinet of the 26th U.S. President, Theodore Roosevelt.

Charles Bonaparte | |

|---|---|

| |

| 46th United States Attorney General | |

| In office December 17, 1906 – March 4, 1909 | |

| President | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | William Moody |

| Succeeded by | George W. Wickersham |

| 37th United States Secretary of the Navy | |

| In office July 1, 1905 – December 16, 1906 | |

| President | Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Paul Morton |

| Succeeded by | Victor H. Metcalf |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Charles Joseph Bonaparte June 9, 1851 Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died | June 28, 1921 (aged 70) Baltimore County, Maryland, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Ellen Channing Day ( m. 1875) |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

Bonaparte was the U.S. Secretary of the Navy and later the U.S. Attorney General.[1] During his tenure as the attorney general, he created the Bureau of Investigation which later grew and expanded by the 1920s under the director J. Edgar Hoover, (1895–1972), as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). It was so renamed in 1935. He was a great-nephew of French Emperor Napoleon I.[2][3][4][5][6]

Bonaparte was one of the founders, and for a time the president, of the National Municipal League. He was also a long time activist for the rights of black residents of his city.[7]

Early life and education

Bonaparte was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on June 9, 1851, the son of Jerôme ("Bo") Napoleon Bonaparte, (1805–1870) and Susan May Williams (1812–1881), from whom the American line of the Bonaparte family descended, and a grandson of Jérôme Bonaparte, the youngest brother of French Emperor Napoleon I and King of Westphalia, 1807–1813. However, the American Bonapartes were not considered part of the dynasty and never used any titles.

Bonaparte graduated from Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1871 and lived in Grays Hall during his freshman year. He then continued to Harvard Law School, where he later served as a university overseer. He practiced law in Baltimore and became prominent in municipal and national reform movements.

Career

In 1899, Bonaparte was the keynote speaker for the first graduating class of the Roman Catholic women's institution run by the Order of the School Sisters of Notre Dame, the College of Notre Dame of Maryland, (now Notre Dame of Maryland University). He spoke on "The Significance of the Bachelor's Degree":

Today, and here for the first time in America, a Catholic college for the education of young ladies bestows the bachelor's degree....

The Style of Scholarship... which benefits the recipient of the bachelor's degree has two distinctive and essential marks. It implies in the first place a broad, generous sympathy with every form of honest, rational and disinterested study or research.

A Scholar who is also, and first of all, a gentleman may be... specially interested is some particular field of knowledge, but he is indifferent to none. He knows how to value every successful effort to master truth; how to look beyond the little things of science... to the great things – God's handiwork as seen in nature, God's mind as shadowed in the workings of the minds of men.Young ladies, if this degree has such meaning for your brothers, what meaning has it for you.[8]

Bonaparte lived in a townhouse in the north Baltimore neighborhood of Mount Vernon-Belvedere and had a country estate in suburban Baltimore County, Maryland, which surrounds the city on the west, north and east. His home, Bella Vista, was designed by the architects James Bosley Noel Wyatt, (1847–1926) and William G. Nolting, (1866–1940), in the prominent local architectural partnership firm of Wyatt & Nolting in 1896.[9] It lies east of the Harford Road (Maryland Route 147) in an area called Glen Arm. The house was not electrified since Bonaparte refused to have electricity or telegraph lines installed from a dislike of technology, verified by his use of horse-drawn coach until his death in the early 1920s.[10]

Politics

A founder of the Reform League of Baltimore, organized in 1885, which eventually led to a certain amount of efficient municipal government with a clean sweep of an election by 1895 in which long-time minority progressive liberal Republicans ousted the long-time Democratic machine politicians in heavily Democratic wards of Baltimore City and ruled with a clean hand for a brief time. He was a member of the Board of Indian Commissioners from 1902 to 1904, chairman of the National Civil Service Reform League in 1904 and appointed a trustee of The Catholic University of America in northeast Washington, D.C.. Maryland voters elected him to be one of their presidential electors in 1904.[11]

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Bonaparte Secretary of the Navy. In 1906 Bonaparte moved to the office of Attorney General, which he held until the end of Roosevelt's term. He was active in suits brought against the trusts and was largely responsible for breaking up the tobacco monopoly. He became known as "Charlie, the Crook Chaser." In 1908, Bonaparte established a Bureau of Investigation (BOI) within the Department of Justice which had been earlier established in 1870 under the direction of the Attorney General himself. By the 1920s, under its long-time director, J. Edgar Hoover, the Bureau had again been cleaned up and streamlined and in 1935 was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Death

Bonaparte died in Bella Vista and is interred at southwest Baltimore's landmark Loudon Park Cemetery. He died of "Saint Vitus Dance" (today called Sydenham's chorea). A nearby street in Baltimore County bears the name of Bonaparte Avenue.

After Bonaparte's death, the house was later owned by bootleggers Peter and Michael Kelly. After they left, it was destroyed in a fire caused by faulty wiring on January 20, 1933. The site was replaced by a poured concrete mansion, but a large carriage house, dating back to 1896, is still on the estate.[9]

Personal life

On September 1, 1875, Bonaparte married the former Ellen Channing Day (1852–1924), daughter of attorney Thomas Mills Day and Anna Jones Dunn. They had no children.

In 1903, he was awarded the Laetare Medal by the University of Notre Dame, the oldest and most prestigious award for American Catholics.[12]

Sources

- Bishop, Joseph Bucklin (1922), Charles Joseph Bonaparte: His Life and Public Services, New York: C. Scribner's Sons

- Goldman, Eric F. (1943), Charles J. Bonaparte: Patrician Reformer, His Earlier Career, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press

References

- Annual Report of the Maryland State Bar Association, vol. 26. Maryland State Bar Association. 1921. pp. 43–45.

- McLynn, Frank (1998). Napoleon. Pimlico. p. 2. ISBN 0-7126-6247-2. ASIN 0712662472.

- "FBI — 1935 Washington Star Article". Fbi.gov. Archived from the original on April 11, 2010. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- Shahab Keshavarz. "Charles J. Bonaparte". Italianhistorical.org. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- http://www.bookrags.com/tandf/bonaparte-charles-joseph-tf/. Retrieved February 17, 2013. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "National Italian American Foundation". Niaf.org. Retrieved August 16, 2013.

- "Baltimore's Civil Rights Heritage (1885–1929)". baltimoreheritage.github.io. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

White Republican party leaders, including prominent Baltimore lawyer Charles J. Bonaparte, also played a role in rallying opposition to these proposals. Historian Jane L. Phelps noted Bonaparte's opposition to the Poe and Strauss Amendments in 1905 and 1908 (Phelps, “Charles J. Bonaparte and Negro Suffrage in Maryland.”) <56>.

- Philbin, Anne Scarborough (1959). The past and the promised. Baltimore, Md.: Alumnae Association, College of Notre Dame of Maryland. p. 58.

- Kelly, Jacques. "Houses – Bella Vista". Baltimore County Public Library Legacy Web. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- Don Bloch (August 18, 1935). "Bonaparte Founded G-Men". FBI. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- Too Close to Call: Presidential Electors and Elections in Maryland, featuring the Presidential Election of 1904. Archives of Maryland Documents for the Classroom.

- "Recipients | The Laetare Medal". University of Notre Dame. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Charles Joseph Bonaparte |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Joseph Bonaparte. |

- Works by or about Charles Joseph Bonaparte at Internet Archive

- Charles Joseph Bonaparte at Find a Grave

- If Walls Could Talk: Chateau Bonaparte on K Street – Ghosts of D.C. blog post on the Bonaparte residence in Washington, DC

| Non-profit organization positions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by |

Chairman of the National Civil Service Reform League 1904 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by James C. Carter |

President of the National Municipal League 1903–1910 |

Succeeded by William D. Foulke |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by Paul Morton |

37th United States Secretary of the Navy July 1, 1905 – December 16, 1906 |

Succeeded by Victor H. Metcalf |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by William H. Moody |

U.S. Attorney General Served under: Theodore Roosevelt December 17, 1906 – March 4, 1909 |

Succeeded by George W. Wickersham |

2.svg.png)