Battle of Graz

The Battle of Graz took place on 24–26 June 1809 between an Austrian corps commanded by Ignaz Gyulai and a French division led by Jean-Baptiste Broussier. The French were soon reinforced by a corps under Auguste Marmont. The battle is considered a French victory though Gyulai was successful in getting supplies to the Austrian garrison of Graz before the two French forces drove him away from the city. Graz, Austria is located 145 kilometers south-southwest of Vienna at the intersection of the modern A2 and A9 highways.

Before the Battle of Raab on 14 June, the Franco-Italian army left Broussier's division in its rear to besiege an Austrian garrison in the Graz citadel. When Gyulai's force appeared before the town in late June, Broussier retreated, allowing the Austrians to resupply the garrison. On the night of 25 June, Broussier sent two unsupported battalions of the 84th Line Infantry Regiment against the town. Surrounded by a greatly superior force of Austrians, the French stubbornly defended their position until the next afternoon, then broke out of the encirclement.

The 84th was soon joined by Auguste Marmont's newly arrived French corps. Marmont then attacked and forced Gyulai to retreat from Graz. The castle hill, however, remained in possession of its Austrian garrison. Shortly afterward, Emperor Napoleon I summoned both Marmont and Broussier to march to Vienna, where both participated in the climactic Battle of Wagram on 5 and 6 July. In recognition of its heroic action, the 84th was allowed to inscribe UN CONTRE DIX (One Against Ten) on its colors.

Background

Situation after Piave River

On 8 May 1809, the Viceroy of Italy, Eugène de Beauharnais and his Franco-Italian army defeated General der Kavallerie Archduke John of Austria at the Battle of Piave River.[5] After the battle, John made the decision to split his army into two parts. He took the troops of Feldmarschall-Leutnants Albert Gyulai and Johann Frimont northeast to Villach and sent Ignaz Gyulai and the IX Armeekorps east toward Ljubljana (Laibach). This dispersal of the available Austrian military units made Eugène's subsequent invasion of Inner Austria considerably easier.[6] John's purpose in sending Ignaz Gyulai to Carniola was to raise the Croatian Feudal Ban, which Gyulai in his capacity as the Ban of Croatia, had the authority to call.[7]

On 15 May, the troops reporting to Archduke John were distributed as follows.[8]

- General der Kavallerie Archduke John of Austria at Tarvisio

- Feldmarschall-Leutnant Albert Gyulai (8,340, 20 guns) at Tarvisio

- Feldmarschall-Leutnant Johann Maria Philipp Frimont (13,060, 22 guns) at Villach

- Feldmarschall-Leutnant Franz Jellacic (10,200, 16 guns) at Radstadt[9]

- Feldmarschall-Leutnant Johann Gabriel Chasteler de Courcelles (17,460, 17 guns) in Tyrol

- Feldmarschall-Leutnant Ignaz Gyulai (14,880, 26 guns) at Kranj

- General-Major Andreas Stoichevich (8,100, 14 guns) in Dalmatia

On the left flank, Eugène retained the 25,000 soldiers from the corps of Generals of Division Paul Grenier and Louis Baraguey d'Hilliers, the Royal Italian Guard, and the cavalry of Generals of Division Emmanuel Grouchy and Louis-Michel Sahuc. On the right flank, General of Division Jacques MacDonald led two infantry divisions and General of Division Charles Randon de Pully's cavalry, altogether 14,000 troops. General of Division Jean-Baptiste Rusca commanded a flank guard that marched on Eugène's left.[10]

Operations

Eugène captured two border forts and defeated Albert Gyulai at the Battle of Tarvis from 15 to 18 May. Archduke John retreated from Villach toward Graz, where he arrived on 24 May.[11] The next day, Grenier's two divisions crushed Feldmarschall-Leutnant Franz Jellacic's division in the Battle of Sankt Michael. Only 2,000 of Jellacic's troops managed to join John at Graz. The rest were killed or captured.[12] On 26 May, Eugène reached Bruck an der Mur and established contact with Napoleon's main army[13] which had occupied Vienna on 13 May.[14]

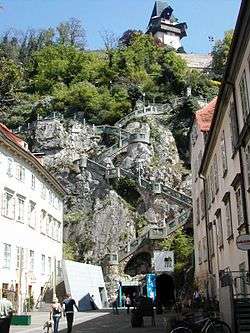

MacDonald occupied Ljubljana on 23 May, capturing 7,000 muskets, 71 artillery pieces, and large supplies of food and munitions.[15] Another French column occupied Trieste, seizing 22,000 British-supplied muskets intended for the use of the Hungarian and Croatian militia. Ordered to move closer to Eugène, MacDonald marched northeast to Maribor (Marburg an der Drau) where he met Grouchy and a cavalry-infantry force. The two then moved north to Graz, arriving on 29 May. As MacDonald and Grouchy approached Graz, Archduke John withdrew[16] to Körmend in Hungary, leaving a garrison on the Graz Schlossberg (castle hill). At this time Ignaz Gyulai's corps lay at Zagreb (Agram) while Archduke Joseph, Palatine of Hungary collected about 10,000 Hungarian Insurrections militia at Győr (Raab).[17]

MacDonald came to an understanding with Graz's Austrian commander. According to the terms, the Austrians evacuated Graz and pulled back into the citadel, allowing the French to occupy the city. If the French wished to attack the fortress, they would do so from outside the city. On the city side of the fortress, a truce prevailed.[16]

In a series of clashes in mid-May, Marmont's XI Corps fought its way north in the Dalmatian Campaign, capturing Stoichevich and mauling his command. The XI Corps reached Fiume on 28 May and Ljubljana on 3 June.[13] At the latter place, Marmont paused because Gyulai's force was located to the east at Zagreb while Chasteler's force from the Tyrol was at large to the north.[18] The survivors of Stoichevich's column joined Gyulai at Zagreb.[19]

Fearful that Chasteler and Gyulai would combine with Archduke John, Eugène ordered a concentration so that he might defeat John before the other two columns could arrive. Accordingly, he drew together forces under Grenier, Baraguey d'Hilliers, and Grouchy. MacDonald left Broussier's division to continue the siege of Graz and hurried to join Eugène.[18]

Aware that Eugène's forces were becoming a danger, Archduke John fell back to the northeast toward Győr to join Archduke Joseph's Hungarian levies. Retreating from the Tyrol with 4,000 to 5,000 troops, Chasteler appeared at Klagenfurt on 9 June.[20] After being repulsed by Rusca, Chasteler slipped past the French and continued on to Maribor.[21] Napoleon ordered Marmont to march to Graz in case Gyulai and Chasteler moved against Broussier.[20] Chasteler briefly joined Gyulai before separating again in a futile effort to catch up with John's army.[19]

On 14 June, Eugène defeated Archduke John's army at the Battle of Raab.[22] John retreated to Komárno on the north bank of the Danube. Covered by Eugène's army, General of Division Jacques Lauriston besieged the fortress of Győr and captured it on 23 June.[23]

Battle

Ignaz Gyulai marched north from Zagreb, reaching Maibor on 15 June. His goal was to bring food and munitions to the besieged garrison of Graz. Marmont arrived at Celje (Cilly) on 19 June. Gyulai feinted to the west, then took the direct road north to Graz via the Mur River valley. Reacting to his opponent's move, Marmont bent his march to the west through Dravograd (Unterdrauberg).[19]

On 24 June, Gyulai's advance guard clashed with Broussier at Karlsdorf south of Graz. A battalion of the Franz Karl Infantry Regiment, a landwehr battalion, two companies of Grenzers, and four squadrons of cavalry confronted five French battalions supported by six artillery pieces. The Frimont Hussars drove back one battalion of the 9th Line Infantry Regiment. The French had the better of the encounter when the untried soldiers of the Massal Austrian landwehr took to their heels.[3]

Broussier raised the blockade of the citadel on the 24th and fell back toward Marmont. On 25 June, Gyulai resupplied the garrison of the castle. That day, Broussier sent two battalions of the 84th Line Infantry Regiment into Graz. The column was without support from the rest of his division.[19]

At 10 pm Colonel Jean Hugues Gambin led 1,200 soldiers and two cannons into Graz's outskirts and rapidly seized 450 surprised Austrian as prisoners. Continuing into Graz, the 84th bumped into an Austrian strongpoint at the Saint Leonhard Church and its nearby cemetery. The French bagged another 125 captives by attacking the place from both front and rear. Becoming aware that he was surrounded by greatly superior forces, Gambin organized a defensive position in the walled cemetery while his voltiguer (light) companies picketed the nearby streets.[2]

At first light, the Austrians began assaulting the trapped Frenchmen, sending attack after attack against the cemetery. One charge broke into the church and liberated all the prisoners. Another thrust by the Simbschen Infantry managed to force its way into the cemetery and haul away one of the two cannons before being driven off. When the attackers seized an eagle, a much-decorated French sergeant waded into a group of Austrians and retook it. There were many other acts of heroism during the 16-hour defense of the position. Finally, the 84th began to run low on ammunition.[2]

Sometime after 1:00 pm on 26 June, Gambin organized and led a last-gasp charge which burst out of the encirclement. The French managed to save their eagles and their one remaining cannon. As they withdrew, they met Marmont's relief column which was marching toward the sound of battle. Immediately, the XI Corps stormed into Graz, smashing down Austrian resistance and ejecting Gyulai's corps from the town. The attackers then ran amok, killing numbers of Austrian wounded and prisoners.[24]

Aftermath

During its inspired defense, the 84th Line lost three officers and 31 men killed, 12 officers and 192 men wounded, and 40 captured. Their attackers suffered an estimated 500 killed and wounded.[24] Altogether, Gyulai's corps lost 2,000 casualties before retreating southeast to Gnas. Marmont set off after Gyulai until 29 May, when he received new orders to join Napoleon at Vienna.[25] Digby Smith gives French losses as 400 killed and wounded, and 500 captured, while numbering Austrian casualties as 164 dead and 816 wounded, captured, and missing.[3]

Despite the victory, Napoleon remarked to Eugène, "Marmont has manoeuvred badly enough; Broussier still worse." He believed that Marmont should have been at Graz by 23 or 24 July and that Gyulai had scared Broussier away from the city. Not only Marmont, but Broussier, Eugene, and other outlying elements of the French emperor's armies were called upon to march immediately to Vienna[26] where they fought in the climactic Battle of Wagram on 5 and 6 July 1809.[27] Napoleon was angry with Broussier for sending two battalions against an entire corps.[19] However, the 84th Line's epic defense pleased him and when Broussier's division arrived at Vienna, the emperor awarded 84 crosses of the Legion d'honneur to deserving officers and soldiers of the regiment. Napoleon made Colonel Gambin a Count of the Empire and allowed the 84th Line Infantry Regiment to inscribe UN CONTRE DIX (One Against Ten) on its colors.[24]

Order of battle

French forces

The French forces that fought at Graz were organized on 5 July 1809 as follows.

- 1st Division of MacDonald's V Corps: General of Division Jean-Baptiste Broussier[28][29]

- Divisional Artillery:

- 8-pdr foot company (6 guns)

- 4-pdr foot company (6 guns)

- 1st Brigade: commander unknown

- 9th Line Infantry Regiment (3 battalions)

- 84th Line Infantry Regiment (3 battalions)

- 2nd Brigade: commander unknown

- 92nd Line Infantry Regiment (4 battalions)

- Divisional Artillery:

- XI Corps: General of Division Auguste Marmont[30]

- Corps Artillery: General of Brigade Louis Tirlet

- Three 12-pdr foot companies (20 guns)

- Seven 6-pdr foot companies (42 guns)

- 1st Division: General of Division Joseph Perruquet de Montrichard

- Divisional Artillery: Two 6-pdr foot companies (12 guns)

- Brigade: Colonel Jean Louis Soye

- 18th Light Infantry Regiment (2 battalions)

- 5th Line Infantry Regiment (2 battalions)

- Brigade: General of Brigade Jean Marie Auguste Aulnay de Launay

- 79th Line Infantry Regiment (2 battalions)

- 81st Line Infantry Regiment (2 battalions)

Bertrand Clausel

Bertrand Clausel

- 2nd Division: General of Division Bertrand Clausel

- Divisional Artillery: Two 6-pdr foot companies (16 guns)

- Brigade: General of Brigade Alexis Joseph Delzons

- 8th Light Infantry Regiment (2 battalions)

- 23rd Line Infantry Regiment (2 battalions)

- Brigade: General of Brigade Gilbert Bachelu

- 11th Line Infantry Regiment (3 battalions)

- Corps Artillery: General of Brigade Louis Tirlet

Austrian forces

On 15 May, Gyulai's and Stoichevich's forces were organized as follows.[31]

- IX Armeekorps: Feldmarschall-Leutnant Ignaz Gyulai

- Corps Artillery: Oberst-Leutnant Johann von Callot[32]

- 12-pdr position battery (6 guns)

- 6-pdr position battery (6 guns)

- Division: Feldmarschall-Leutnant Anton von Zach (14,880)

- Brigade: General-Major Johann Kalnássy

- Simbschen Infantry Regiment Nr. 43 (2 battalions)

- Szluiner Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 4 (1 battalion)

- Brigade: General-Major Alois von Gavasini

- Archduke Franz Karl Infantry Regiment Nr. 52 (2 battalions)

- Ottocaner Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 2 (2 battalions)

- Brigade: General-Major Ignaz Splényi

- Brigade: General-Major Joseph Munkácsy

- Brigade: Oberst Matthias Rebrovich vice General-Major Andreas Stoichevich (8,100)[33]

- Liccaner Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 1 (2 battalions)

- Szent George Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 6 (2 battalions)

- Deutsch Banat Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 12 (1 battalion)

- Karlstadt Reserve Landwehr (4 battalions)

- Garrison Regiment Nr. 4 (1 battalion)

- Hohenzollern Chevau-léger Regiment Nr. 2 (1 squadron)

- 3-pdr Grenz brigade battery (8 guns)

- 6-pdr position battery (6 guns)

- Brigade: General-Major Johann Kalnássy

- Corps Artillery: Oberst-Leutnant Johann von Callot[32]

Notes

- Epstein, p 144

- Arnold, p 114

- Smith, p 318

- Bowden & Tarbox, p 154. The authors give Marmont's strength at Wagram as 10,700.

- Schneid, pp 80-82

- Schneid, p 82

- Epstein, p 119

- Bowden & Tarbox, pp. 115–117

- Petre, pp 224-226. Bowden & Tarbox reported that Jellacic was at Salzburg on 15 May, but Petre wrote that he evacuated it on 29 April and moved south to Radstadt.

- Epstein, p 122

- Epstein, pp 123-124

- Schneid, pp 85-87

- Epstein, p 126

- Petre, p 259

- Epstein, pp 126-127

- Epstein, p 127

- Epstein. p 130

- Epstein, p 134

- Petre, p 315

- Epstein, p 135

- Petre, p 309

- Smith, p 315

- Epstein, p 143

- Arnold, p 115

- Petre, p 316

- Petre, p 327

- Smith, pp 318-320

- Bowden & Tarbox, p 148. This is the organization at Wagram on 5 and 6 July.

- Epstein, p 188. Epstein provides corps numbers for Eugène's army.

- Bowden & Tarbox, pp 150-151

- Bowden & Tarbox, pp 116-117

- Bowden & Tarbox, p 107. Callot was the IX Armeekorps artillery chief at the outbreak of war.

- Arnold, p 113. Stoichevich was captured on 16 May.

References

- Arnold, James R. Napoleon Conquers Austria. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 1995. ISBN 0-275-94694-0

- Bowden, Scotty & Tarbox, Charlie. Armies on the Danube 1809. Arlington, Texas: Empire Games Press, 1980.

- Epstein, Robert M. Napoleon's Last Victory and the Emergence of Modern War. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1994.

- Petre, F. Loraine. Napoleon and the Archduke Charles. New York: Hippocrene Books, (1909) 1976.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (2007). Napoleon’s Great Adversary: Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army 1792–1914. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-383-2.

- Schneid, Frederick C. Napoleon's Italian Campaigns: 1805-1815. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-275-96875-8

- Smith, Digby. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill, 1998. ISBN 1-85367-276-9

External links

- napoleon-series.org Austrian Generals 1792-1815 by Digby Smith, compiled by Leopold Kudrna

- French Wikipedia, Liste des généreaux de la Révolution et du Premier Empire