Battle of Fère-Champenoise

The Battle of Fère-Champenoise (25 March 1814) was fought between two Imperial French corps led by Marshals Auguste de Marmont and Édouard Mortier, duc de Trévise and a larger Coalition force composed of cavalry from the Austrian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia, Kingdom of Württemberg, and Russian Empire. Caught by surprise by Field Marshal Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg's main Coalition army, the forces under Marmont and Mortier were steadily driven back and finally completely routed by aggressive Allied horsemen and gunners, suffering heavy casualties and the loss of most of their artillery. Two divisions of French National Guards under Michel-Marie Pacthod escorting a nearby convoy were also attacked and wiped out in the Battle of Bannes. The battleground was near the town Fère-Champenoise located 40 kilometres (25 mi) southwest of Châlons-en-Champagne.

| Battle of Fère-Champenoise | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Sixth Coalition | |||||||

Painting by Bogdan Willewalde | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

26,400 128 guns 180,000 reinforcements |

22,450 84 guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 2,000-4,000 |

10,000 60-80 guns lost 225-250 wagons captured | ||||||

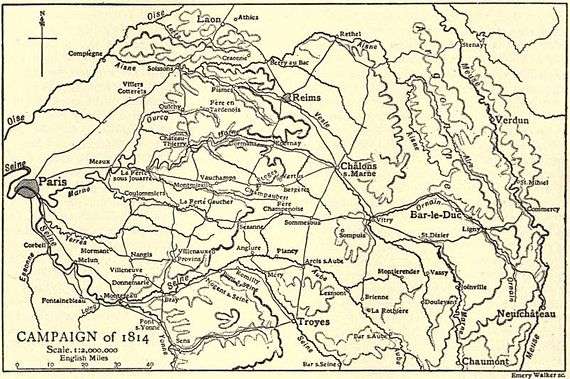

After being defeated at the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube on 20–21 March 1814, Emperor Napoleon moved to the east. He hoped to draw the Coalition armies away from Paris by cutting their supply lines, but Schwarzenberg's army instead began moving west toward Paris. Meanwhile, Marmont and Mortier were marching to join Napoleon, pursued by Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher's Allied army. As the two marshals moved east near Fère-Champenoise they unexpectedly came into collision with Schwarzenberg heading west and Blücher moving south. Belatedly realizing they were marching into a trap, the French began a withdrawal to the west. After six hours of orderly retreat, a sudden violent rainstorm made it difficult for the French foot soldiers to fire their muskets and the Allies' enormous superiority in cavalry proved decisive. With the corps of Marmont and Mortier crippled, the Allied capture of Paris was practically inevitable and the Battle of Paris followed on 30 March.

Background

Napoleon's operations

On 9–10 March 1814, Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher's 100,000-man Coalition army defeated Napoleon's 39,000-strong army in the Battle of Laon.[1] After drubbing the French on 9 March, Blücher became incapacitated by fever and an eye ailment, so command devolved upon his chief of staff August Neidhardt von Gneisenau. Though Gneisenau was a brilliant strategist, he was not capable of leading an army. The acting commander allowed his beaten foes to continue the fight the next day and then slip away that night without being pursued.[2] On 13 March, Napoleon fell on Emmanuel de Saint-Priest's Russian VIII Corps and a Prussian brigade in the Battle of Reims.[3] The Allied force was scattered with losses of 3,000 men and 23 guns, including Saint-Priest who was fatally wounded.[4]

After three days of reorganization, Napoleon left Auguste de Marmont and Édouard Mortier, duc de Trévise with 21,000 troops to watch Blücher while he tried to outflank Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg's main army by moving against Arcis-sur-Aube. Marshal Michel Ney marched southeast from Reims to recapture Châlons-sur-Marne.[5] At this time, Schwarzenberg's army threatened to cross the Seine River and press back Marshal Jacques MacDonald's wing of the French army. News of Saint-Priest's rout reached Coalition headquarters on 16 March. This prompted the Austrian field marshal to make the intelligent decision to fall back and reassemble his army between Troyes and Arcis-sur-Aube.[6]

Believing that it was only necessary to deliver a sharp blow to send the cautious Schwarzenberg into retreat, Napoleon occupied Arcis at mid-day on 20 March. Soon after, a large body of Coalition horsemen threw back the French cavalry, but the situation was stabilized that evening after a tough struggle. The next day, Napoleon ordered an attack only to find his 28,000 soldiers facing 80,000 Allies. Thanks to Schwarzenberg's hesitation, the French emperor quickly pulled his army to the north bank of the Aube River covered by stout rearguard fighting,[7] but the Battle of Arcis-sur-Aube on 20–21 March was a Coalition victory.[8]

After this setback, Napoleon determined to operate against the Allied supply line stretching back to the Rhine River while adding the fortress garrisons to his army. Accordingly, he moved northeast toward Vitry-le-François with the intention of continuing east along the Marne River to Saint-Dizier.[9] By this maneuver, the French emperor hoped to lure the Allies after him and away from Paris.[10]

MacDonald's wing was in great peril as it moved east on the north bank of the Aube. Though Marshal Nicolas Oudinot's corps held the northern suburb of Arcis-sur-Aube, MacDonald's own corps only reached the vicinity of Arcis at 9:00 pm on 21 March. Étienne Maurice Gérard's corps was farther west at Plancy-l'Abbaye while François Pierre Joseph Amey's division brought up the rear at Anglure. Jean François Leval's rearguard successfully destroyed the bridges and the Allies did not attempt to force their way across the Aube that evening.[11] Because of Allied inertia, MacDonald successfully held the north bank of the Aube on 22 March. Finding Vitry-le-François solidly held by 5,000 Russians, Napoleon with Ney's corps, the Imperial Guard and his cavalry crossed the Marne south of the town and continued toward Saint-Dizier. On the way, the French light cavalry seized a Coalition convoy and dispersed its two-battalion escort.[12]

On the night of 22 March, MacDonald's troops silently left their blocking position opposite Arcis-sur-Aube and marched through Dosnon and Sommesous toward Vitry-le-François. Amey was supposed to guard the artillery park, but by a misunderstanding, that general marched his division northwest to Sézanne. Consequently, the Russian Guard Light Cavalry Division attacked the unguarded wagon train, carrying off 15 artillery pieces and 300 prisoners while destroying the gunpowder and spiking 12 cannons. Coming on the scene, Gérard's corps rescued what was left of MacDonald's artillery park. Despite constant skirmishing with Karl Philipp von Wrede's Allied corps during the day, MacDonald got his troops safely across the Marne late on 23 March. At that hour, Napoleon was in Saint-Dizier with his Guard while Ney was between there and Vitry.[13]

Marmont's operations

Blücher's army finally lurched into motion on 18 March, with its commander wearing a lady's green silk hat in order to protect his inflamed eyes from the sun. On this day, Ludwig Yorck von Wartenburg's corps compelled Étienne Pierre Sylvestre Ricard's division to abandon Berry-au-Bac though the French managed to destroy the bridge over the Aisne River. Marmont had overall command of the forces facing Blücher and his orders were to cover Paris and stop his foes from crossing the Aisne. Mortier was at Reims while Henri François Marie Charpentier's division held Soissons.[14] Since Blücher had 109,000 troops while the French only mustered 13,000 infantry and 3,600 cavalry, it was plain that the Allies could not be stopped for long.[15] In order to block the road to Paris and to rendezvous with Charpentier, Marmont fell back southwest toward Fismes and called in Mortier from Reims. He believed that Blücher wished to bring him to battle, but in fact the Prussian field marshal was heading for Reims and Châlons-sur-Marne to link up with Schwarzenberg.[16]

Blücher assigned only the corps of Yorck and Friedrich Graf Kleist von Nollendorf to follow Marmont.[16] By 19 March, Blucher had established two bridges over the Aisne and sent Ferdinand von Wintzingerode's corps south to capture Reims.[17] Wintzingerode occupied Reims at daybreak on 20 March after it was evacuated by Augustin Daniel Belliard who led Mortier's cavalry. At this hour, Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron's Russian corps was at Berry-au-Bac while Fabian Gottlieb von Osten-Sacken's Russian corps was nearby at Pontavert. Blücher ordered Wintzingerode to hold Reims with his infantry and send his cavalry to Épernay and Vitry-le-François. Charpentier left a 2,800-man garrison in Soissons before pulling out to join Marmont and Mortier. On 21 March, there was a cavalry scuffle at Oulchy-le-Château between Yorck and Kleist's cavalry and the French, but the Prussians did not pursue.[18] Having picked up Charpentier's division, Marmont and Mortier crossed the Marne at Château-Thierry and destroyed the bridge. Also on the 21st, Marmont received a dispatch from Napoleon rebuking him for not retreating from Reims toward Châlons-sur-Marne and ordering him to move back in that direction. On 22 March, the two marshals headed east toward Étoges. That day Friedrich Wilhelm Freiherr von Bülow's Prussian corps appeared before Soissons and began bombarding the place.[16]

By nightfall on 23 March, Marmont's troops were in Vertus while Mortier's corps reached Étoges.[19] That evening near Bergères-lès-Vertus, Christophe Antoine Merlin's French advance guard drove off some Allied cavalry, capturing 100 troopers and 16 wagon loads of plunder. A French staff officer found some enemy dispatches in Vertus that indicated the armies of Schwarzenberg and Blücher might link up and march toward Paris. The two marshals believed they were planted to trick the French so the information was disregarded.[20][note 1] By the evening of 23 March, Oudinot and MacDonald's corps arrived at Saint-Dizier, Ney's troops were to the south at Wassy and Napoleon and the Imperial Guard were yet farther south at Doulevant-le-Château. Well in advance of the rest, Napoleon's cavalry reached Colombey-les-Deux-Eglises near Bar-sur-Aube.[19] On 23 March, the divisions of Michel-Marie Pacthod with 4,000 men and Amey with 1,800 men reached Sézanne. They found an 80-wagon food and equipment convoy in the village with its escort of 800 foot soldiers and one squadron of the 13th Hussar Regiment. Finding that Marmont and Mortier were nearby, they set out with the convoy toward Étoges. Soon after they left Sézanne, Jean Dominique Compans arrived in the village to set up a communications base, followed by two cavalry march regiments.[21]

On 23 March, Wintzingerode with 8,000 cavalry and 40 guns arrived near Vitry-le-François while Mikhail Semyonovich Vorontsov with Wintzingerode's infantry plus Langeron and Sacken were coming up behind. Yorck and Kleist reached Château-Thierry. After a captured French message indicated that Napoleon was at Saint-Dizier,[22] the Allies decided to merge their two armies and go after Napoleon with 200,000 troops. With the French emperor already blocking their supply line to Germany, the Allies determined to establish a new line from the Netherlands to Laon. At Bar-sur-Aube, Emperor Francis I of Austria was warned to leave for Dijon.[23] Francis fled to safety with the Austrian Army of the South a few hours ahead of the French cavalry.[14] On the evening of 23 March, a message from Napoleon's Chief of Police Anne Jean Marie René Savary was intercepted by Friedrich Karl von Tettenborn's Cossacks. It stated that there was nothing in the arsenals and treasury at Paris and that the city's increasingly restive population was demanding peace. More information arrived from Napoleon's enemies in Paris.[24]

After looking at the captured messages, Czar Alexander I of Russia at his headquarters at Sompuis concluded that the Allied armies should advance on Paris. He asked Michael Andreas Barclay de Tolly, Hans Karl von Diebitsch and Karl Wilhelm von Toll for their advice. Barclay wished to follow Napoleon[24] but Toll wanted to move on Paris while sending 10,000 cavalry to hide the maneuver from Napoleon. After Diebitsch came around to Toll and Alexander's point of view, they convinced first King Frederick William III of Prussia and then Schwarzenberg of their plan.[25] On 24 March, Schwarzenberg's army moved north toward Vitry-le-François,[24] but new orders were issued for the following day. Wintzingerode was instructed to chase after Napoleon with his cavalry force. The VI Corps supported by the IV Corps were ordered to march west toward Fère-Champenoise with their combined cavalry in front. The Guards and Reserves were directed on the same place from Sompuis[25] while the III Corps was to move north from Mailly-le-Camp. Vorontsov, Langeron and Sacken of Blücher's army were instructed to move west from Châlons-sur-Marne toward Étoges. By the evening of 24 March, Schwarzenberg's host was near Vitry,[26] on the east bank of the Coole (Côle) River.[27]

Battle

Fighting withdrawal

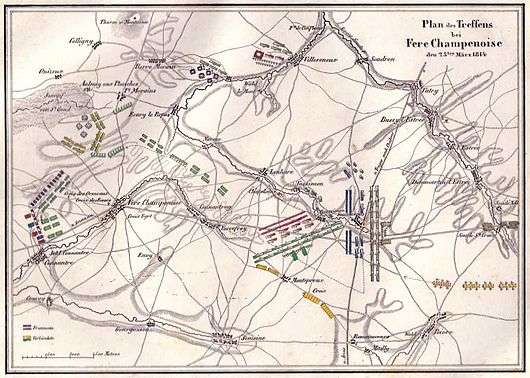

After a lively debate between Belliard and the two marshals over what was the best route to approach the Marne, on 24 March the French marched through Fère-Champenoise and Vatry. Henri Catherine Balthazard Vincent moved toward Montmirail[20] with 300 men watch for Yorck and Kleist.[28] During the day, Mortier's cavalry scouted in the direction of Châlons and Saint-Quentin-sur-Coole, finding only a few hundred enemy cavalry in Châlons and no Allied troops near Nuisement-sur-Coole. Marmont scouted toward Maisons-en-Champagne and found no enemies. Based on these reports, the two marshals decided that Schwarzenberg was south of Saint-Dizier, maneuvering against Napoleon. Bolstered in their opinions by the day's reconnaissances, Marmont and Mortier failed to reconsider even when large numbers of campfires were observed that night beyond the Coole. Marmont's troops camped between Vatry and Soudé while Mortier's bivouacked farther north.[27]

On 25 March at 3:30 am Peter Petrovich Pahlen began to send out patrols at the request of Crown Prince Frederick William of Württemberg. The Allied advance was conducted in two columns. The first column on the main highway west from Vitry-le-François consisted of the Crown Prince (IV Corps) and Nikolay Raevsky (VI Corps), followed by Wrede (V Corps). The second column on more a southerly route through Montépreux was composed of the Guard and Reserves while Ignaz Gyulai (III Corps) was directed to march toward Semoine. From Coole[27] Pahlen's 3,600 cavalry led the advance of the first column until his horsemen appeared before Soudé between 6:00 and 8:00 am. Meanwhile, Mortier's corps was on the march at 6:00 from Vatry toward Soudé with Nicolas-François Roussel d'Hurbal's dragoons leading the column.[27]

Startled when Pahlen's guns began bombarding his positions, Marmont deployed his own infantry and artillery on a rise to the west of Soudé and sent a note for Mortier to quickly join him. Sensing Marmont's alarm, Pahlen and Prince Adam of Württemberg chose to attack at once. Pahlen sent Dechterev's brigade around Marmont's left flank, Delivanov's brigade against the French center and Lissanovich's brigade and Illowaisky's 1,000 Cossacks north to Dommartin-Lettrée. Prince Adam and the Württemberger cavalry operated on Marmont's right flank while Nikolay Vasilyevich Kretov's Cuirassier Division and 12 guns[29] of Markov's 23rd Horse Artillery Battery supported the center attack. Very soon the Allies had 10,000 cavalry on the field to oppose 4,934 French cavalry. This included 2,305 troopers from Johann Nepomuk von Nostitz-Rieneck's Austrian Cuirassier Division. With both his flanks turned Marmont ordered a retreat. When his cavalry under Étienne Tardif de Pommeroux de Bordesoulle moved forward it was beaten back with heavy losses. Two French light companies in Soudé were swallowed up by the Allied cavalry.[30]

When Mortier's corps reached Dommartin-Lettrée, Belliard's cavalry shoved Pahlen's cavalry out of the way. However, Illowaisky's Cossacks managed to cut off Charpentier's division at the rear of the column, forcing it to head for Sommesous. Marmont finally united the two corps at Sommesous and placed his cavalry in the first line and his infantry in the second line. He deployed Mortier on the left with his flank covered by Charles Étienne de Ghigny's horsemen. The French put 60 guns in action which dominated the Allies' 36 available guns in a two-hour artillery duel. Menaced by Illowaisky's Cossacks, the French pulled their left flank back behind the stream flowing northwest from Sommesous. On the opposite side of the stream were the Cossacks and Dechterev's brigade near Lenharrée. About noon, François Joseph Desfour's Austrian cuirassier brigade charged together with the Archduke Ferdinand Hussar Nr. 3 and 4th Württemberg Mounted Jäger Regiments. In the face of this attack, Marmont began to draw back into a position where both his flanks were protected by streams.[31]

Marmont's defeat

Prince Adam's charge pressed back the right flank French cavalry, but when the Liechtenstein Cuirassier Regiment tried to exploit the success, it was blasted by canister shot and hit in the flank by French lancers. Prince Adam paused to reorganize his horsemen.[32] At the same time, Nostitz and Pahlen charged the French left and became embroiled in a melee with the cavalry divisions of Roussel d'Hurbal and Merlin. The Allies were more successful and managed to capture five French field pieces near Lenharrée. At Connantray-Vaurefroy the retreating French began to cross a small stream lined with trees running through a depression. At the moment they were negotiating this obstacle, a powerful storm from the east blew first dust and then rain and hail into the faces of the French. Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich of Russia leading Nikolay Ivanovich Depreradovich's crack 1st Russian Cuirassier Division and the Russian Guard Dragoons and Guard Uhlans charged the French right flank as Pahlen attacked the French left.[33]

The massed Allied cavalry charge routed Bordesoulle's cavalry which was disorganized by crossing the stream. After the French horsemen galloped to the rear, the Coalition cavalry broke two regiments of Young Guard that failed to form square in time. Many French soldiers were cut down, eight cannons were seized and brigade commander Jean Baptiste Jamin de Bermuy became a prisoner. In the rainstorm, the French infantrymen could no longer fire their wet muskets. Jacques Le Capitaine's 1,000-man brigade repelled three cavalry charges while in square, but a fourth charge smashed the formation, inflicting heavy losses. During this time a Russian Guard artillery battery took the French under accurate fire. Fortunately for the French, the divisions Ricard and Charles-Joseph Christiani, at the ends of the line held firm, allowing a brief rally. A French Young Guard brigade supported by eight 12-pound cannons repelled two charges by the Archduke Ferdinand Hussars. At this point, Alexander Nikitich Seslavin's Cossacks appeared on the field, prompting the survivors of Jamin's mauled brigade to run away.[34]

The panic spread and Marmont's entire force streamed to the rear. The French were saved when the 400-strong 9 March Regiment, made up of heavy cavalry, arrived from Sézanne and drove off the pursuing Allied horsemen. In the breathing space, Marmont and Mortier reorganized their battered corps in two lines near Fère-Champenoise. Hearing the sounds of approaching gunfire, the French soldiers quickly rallied and cheered "Long live the emperor!" believing that Napoleon was coming to their rescue.[35] Actually, the sounds were from the Coalition attacks on Pacthod's force. The Allied generals swiftly called off most of their cavalry to concentrate on Pacthod's destruction. Nevertheless, Marmont's troops were soon hustled off the field by Seslavin's Cossacks and reached Allemant at 9:00 pm.[36]

Pacthod's disaster

Pacthod's force departed from Vatry at dawn, having marched most of the night with the convoy. By 10:00 am Pacthod was in Villeseneux where he decided to rest his weary soldiers. At this time, the force came under attack from 1,200 dragoons and horse chasseurs supported by 12 guns under Fyodor Karlovich Korf. Pacthod anchored his right flank on Villeseneux while Amey's entire division in square formed his left flank and 16 French guns covered the front.[36] Korff's cavalry corps belonged to Langeron's army corps.[37] For 90 minutes, the French moved southwest deployed in six masses while easily fending off Korf's horsemen. At Clamanges Pacthod made the decision to abandon the convoy, taking the teams of horses to help haul his artillery pieces. More Russian cavalry arrived until Korf's force comprised 2,000 line cavalry and 1,000 Cossacks. Two horse chasseur regiments circled around to the west, blocking the French retreat toward Fère-Champenoise. One of Pacthod's brigades under Marie Joseph Raymond Delort formed attack columns and drove off the chasseurs.[38] Between 2:00 and 3:00 pm the French reached Écury-le-Repos when more Allied cavalry came on the scene.[37]

The sounds of Delort's action drew the cavalry of Sacken's army corps in the form of the 2nd Hussar Division under Ilarion Vasilievich Vasilshikov. To help Korf's tiring horsemen, Vasilshikov's hussars charged the French from the north and forced them to form square. Simultaneously, Schwarzenberg, Czar Alexander and King Frederick William III arrived on the battlefield and set up their headquarters in Fère-Champenoise. Kretov sent a note to the czar that Pacthod's French troops were headed his way. At first Kretov's report was not credited but soon the Allied sovereigns could see for themselves that a French force was approaching. Czar Alexander ordered the Prussian Guard Cavalry and the Russian Guard Hussars and Guard Cossacks into the fight and instructed the 23rd Horse Battery to open fire on Pacthod's men. Because the French were in low ground, the Russian round shot and canister sailed over them and began striking Vasilshikov's horsemen. Returning fire, Vasilshikov's gunners nearly hit the czar's entourage with friendly fire when four round shots landed nearby. After sorting out the confusion, the czar ordered Korff and Vasilshikov not to charge in order to let the Allied artillery batter Pacthod's squares.[39] Pahlen's cavalry were recalled from the fight against Marmont and sent to block Pacthod on the southwest while 30 Russian guns blasted the French from the south.[37]

As Pacthod's situation became increasingly dire, he ordered his force to march toward the Marshes of Saint-Gond. Despite being ringed by enemy cavalry, his National Guardsmen held firm in their square formations.[39] Vasilshikov led the Guard Cavalry plus two dragoon and one horse chasseur regiments in a sweeping charge but the horsemen were driven off by intense musketry. By this time 78 Russian guns were pummeling Pacthod's squares with canister, causing casualties and increasing disorder. Louis Marie Joseph Thévenet's brigade of Amey's division fought its way as far west as Bannes before being blocked by the elite Russian Chevalier Guard Regiment. Three Russian officers and a trumpeter came forward under a flag of truce to demand Pacthod's surrender. The French general refused to negotiate as long as the enemy artillery were firing and made one of the officers a prisoner; another was shot dead by a foot soldier. In a climactic charge, the massed Russian cavalry broke the square on the French right flank and then overran the other squares, one after the other. In the subsequent melee, the French soldiers were cut down or surrendered and generals Pacthod, Amey, Delort, Thévenet and Marie Louis Joseph Bonté became Allied prisoners.[40] The raw National Guardsmen made a gallant defense but barely 500 men escaped the slaughter.[41]

Forces

According to historian George Nafziger, the Allies employed 26,400 cavalry and 128 artillery pieces. Crown Prince Frederick William commanded 2,000 Württembergers and 12 guns, 3,500 Russians and 12 guns in Palen's Cavalry Corps and 1,600 Russians and 12 guns in Kretov's 2nd Cuirassier Division. Nostitz led 3,700 Austrians and 24 guns in his own Cuirassier Division and two regiments of chevau-légers. Grand Duke Konstantin directed 1,600 Russians and 12 guns from the Guard Cuirassier Division and 2,400 Russians and 12 guns from the Guard Light Cavalry Brigade. In addition, there were 800 Prussian Guards and eight guns, 5,400 Russians and 22 guns in Korf's Cavalry Corps, 3,900 Russians and 12 guns in Vasilshikov's 2nd Hussar Division and Seslavin's 1,500 Don Cossacks and two guns.[42]

Nafziger stated that the French used 18,100 foot soldiers, 4,350 horsemen and 84 guns.[43] Mortier's command included 7,400 Imperial Guard infantry and 30 guns in three divisions led by Christiani, Philibert Jean-Baptiste Curial and Charpentier. Mortier also had 2,050 line cavalry under Roussel d'Hurbal and Ghigny. Marmont's corps consisted of 4,900 line infantry and 38 guns in the divisions of Ricard, Joseph Lagrange and Jean-Toussaint Arrighi de Casanova.[42] Marmont's 2,300 line cavalry were led by Bordesoulle and Merlin. Pacthod directed 5,800 French National Guards and 16 guns in his own and Amey's divisions.[43] On 15 March unit strengths were somewhat larger. In Mortier's corps, Christiani had 2,100 men, Curial 2,800, Charpentier 2,800, Roussel d'Hurbal 1,750 and François Grouvel 350 horsemen. In Marmont's corps, Ricard had 1,000 soldiers, Lagrange 2,100, Arrighi 2,100, Merlin 1,150 and Bordesoulle 1,250.[44]

Francis Loraine Petre estimated the strength of Marmont and Mortier as 19,000 troops and of Pacthod as 4,300 men.[37] Digby Smith asserted that the French marshals had 17,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry and 84 guns, while the Allies had 28,000 troops, mostly cavalry, and 80 guns.[45] Smith credited Pacthod with a total of 3,700 infantry, 100 cavalry and 16 guns. Two of Pacthod's and one of Amey's battalions were line infantry, the rest of the foot soldiers were National Guards.[46] David G. Chandler stated that Pacthod had 4,000 soldiers without giving Marmont and Mortier's strength.[41] Spencer C. Tucker gave French strength as 5,000.[47]

Results

.jpg)

Petre reckoned French losses as 10,000 men and over 60 guns and Allied losses as 2,000. Marmont and Mortier lost 2,000 killed and wounded with 4,000 soldiers, 45 guns and 100 ammunition wagons captured. Pacthod lost almost his entire force of 4,300 men, 16 guns and the convoy, with only a handful escaping into the Saint-Gond Marshes.[48] Nafziger gauged losses as 9,000–11,000 French soldiers, including 5,000 killed and wounded, and 4,000 Allied casualties. The Allies claimed to have taken 80 cannons and 250 ammunition wagons.[40] Smith stated that Pacthod lost 1,500 killed and wounded plus 1,900 soldiers, 100 ammunition wagons and 125 bread wagons captured. His National Guards fought like veterans.[46] For Marmont's force, Smith quoted one source that estimated 5,000 killed and wounded plus 8,000 men, 46 guns and 20 ammunition wagons captured. A second source gave 1,500–3,000 killed and wounded, 3,000 captured and 2,000 deserted.[45]

Marmont and Mortier spent the night after the battle at Allemant, to the northeast of Sézanne. Hearing that Yorck sent a force under Hans Ernst Karl, Graf von Zieten toward Sézanne, Compans abandoned the town at midnight and marched to join the two marshals at Allemant. Two hours later Marmont and Mortier began moving toward Sézanne.[42] The next morning they found Zieten in possession of the town, but their superior numbers persuaded the Prussian to withdraw after a skirmish that cost the French 200 casualties and their opponents 107.[43] Leading the Coalition pursuit, the Crown Prince of Württemberg entered Sézanne three hours after the French left. On 26 March, Compans with 1,000 men marched west through La Ferté-Gaucher and reached Coulommiers after some clashes with a Prussian brigade led by Heinrich Wilhelm von Horn. At Coulommiers where he spent the night, Compans was joined by Vincent's observation force and fugitives from the battle, raising his force to 2,200 infantry and 250 cavalry.[49]

When Marmont and Mortier arrived at La Ferté-Gaucher, they found Prince Wilhelm of Prussia's brigade blocking them.[49] Prince Wilhelm was gradually reinforced by elements of Kleist's corps and the Prussian artillery soon dominated the numerically weaker French guns. After unsuccessfully trying to push the Prussians out of the way and learning that Pahlen's cavalry corps was approaching from the east, the French marshals decided they could only escape the trap by marching south to Provins.[50] Far to the east, Napoleon scored a pointless victory over Wintzingerode in the Battle of Saint-Dizier on 26 March. The next day, the French emperor finally realized that the Allies had called his bluff and were advancing on Paris. He ordered his troops to march toward the capital, but it was too late.[51]

Marmont and Mortier reached Provins on 27 March and turned toward Paris.[52] That day Compans was in Meaux, reinforced to a strength of 3,800 foot soldiers and 850 horsemen. This was far too few men and by 28 March, the combined Allied armies bridged the Marne and captured Meaux.[53] Compans was driven back along the direct road to Paris, where he arrived on 29 March and was joined Marmont and Mortier who came by the roundabout route through Provins. On 30 March, the French with 42,000 men, including only 23,000 veterans, faced Schwarzenberg and Blücher with 107,000 troops. After the Battle of Paris and the subsequent surrender of the capital, Napoleon's empire came to an end.[54]

Notes

- Footnotes

- On pages 332–335, Nafziger's text substitutes Oudinot for Marmont. On other pages Nafziger correctly names the two marshals as Marmont and Mortier. Oudinot was with Napoleon's army during this time.

- Citations

- Smith 1998, p. 510.

- Petre 1994, pp. 144–147.

- Smith 1998, p. 511.

- Petre 1994, p. 150.

- Petre 1994, pp. 155–156.

- Petre 1994, pp. 159–160.

- Chandler 1966, pp. 996–998.

- Smith 1998, p. 512.

- Petre 1994, pp. 177–178.

- Petre 1994, p. 175.

- Petre 1994, p. 176.

- Petre 1994, pp. 179–180.

- Petre 1994, p. 181.

- Petre 1994, p. 184.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 328.

- Petre 1994, p. 185.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 329.

- Nafziger 2015, pp. 330–331.

- Petre 1994, p. 186.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 334.

- Nafzgier 2015, p. 335.

- Petre 1994, p. 182.

- Petre 1994, p. 183.

- Petre 1994, p. 187.

- Petre 1994, p. 188.

- Petre 1994, p. 189.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 401.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 335.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 402.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 404.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 405.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 406.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 407.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 408.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 409.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 410.

- Petre 1994, p. 191.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 411.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 412.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 413.

- Chandler 1966, p. 1000.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 415.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 416.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 307.

- Smith 1998, p. 514.

- Smith 1998, p. 515.

- Tucker 2009, p. 1113.

- Petre 1994, pp. 191–192.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 417.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 418.

- Petre 1994, pp. 193–196.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 420.

- Nafziger 2015, p. 419.

- Petre 1994, pp. 198–200.

References

- Chandler, David G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York, N.Y.: Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nafziger, George (2015). The End of Empire: Napoleon's 1814 Campaign. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1-909982-96-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petre, F. Loraine (1994) [1914]. Napoleon at Bay: 1814. London: Lionel Leventhal Ltd. ISBN 1-85367-163-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. p. 1113. ISBN 978-1851096725.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

See also

- Fershampenuaz, a village in Russia named in memory of the battle.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Fere-Champenoise. |

↑ The Battle of La Fère-Champenoise, 1814