First Republic of Venezuela

The First Republic of Venezuela (Spanish: Primera República de Venezuela) was the first independent government of Venezuela, lasting from 5 July 1811, to 25 July 1812. The period of the First Republic began with the overthrow of the Spanish colonial authorities and the establishment of the Junta Suprema de Caracas on 19 April 1810, initiating the Venezuelan War of Independence, and ended with the surrender of the republican forces to the Spanish Captain Domingo de Monteverde. The congress of Venezuela declared the nation's independence on 5 July 1811, and later wrote a constitution for it. In doing so, Venezuela is notable for being the first Spanish American colony to declare its independence.

American Confederation of Venezuela/States of Venezuela/United States of Venezuela Confederación americana de Venezuela/Estados de Venezuela/Estados Unidos de Venezuela | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1811–1812 | |||||||||||||

The First Republic of Venezuela | |||||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized state | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Valencia | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||||||

| Government | Republic | ||||||||||||

| Triumvirate | |||||||||||||

• 1811–12 | Cristóbal Mendoza, Juan Escalona, Baltazar Padrón | ||||||||||||

• 1812 | Francisco Espejo, Fernando Rodriguez, Francisco J. Ustariz | ||||||||||||

• 1812 | Francisco de Miranda | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Spanish American wars of independence | ||||||||||||

| 5 July 1811 | |||||||||||||

| 25 July 1812 | |||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | VE | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

History

Antecedents

Several European events set the stage for Venezuela's declaration of independence. The Napoleonic Wars in Europe not only weakened Spain's imperial power, but also put Britain unofficially on the side of the independence movement. In May 1808, Napoleon asked for and received the abdication of Ferdinand VII and the confirmation of his father Charles IV's abdication a few months earlier. Napoleon then made his brother Joseph Bonaparte, King of Spain. That marked the beginning of Spain's own War of Independence from French hegemony and partial occupation, before the Spanish American wars of independence even began. The focal point of the Spanish political resistance was the Supreme Central Junta, which formed itself to govern in the name of Ferdinand, and which managed to get the loyalty of the many provincial and municipal juntas that had formed throughout Spain in the wake of the French invasion. Likewise, in Venezuela during 1809 and 1810 there were various attempts at establishing a junta, which took the form of both legal, public requests to the Captain General and secret plots to depose the authorities.[1] The first major defeat that Napoleonic France suffered was at the Battle of Bailén, in Andalusia. (At this battle Pablo Morillo, future commander of the army that invaded New Granada and Venezuela; Emeterio Ureña, an anti-independence officer in Venezuela; and José de San Martín, the future Liberator of Argentina and Chile, fought side-by-side against the French General Pierre Dupont.) Despite this victory, the situation soon reversed itself and the French advanced into southern Spain and the Spanish government had to retreat to the island redout of Cádiz. In Cádiz, the Supreme Central Junta dissolved itself and set up a five-person Regency to handle the affairs of state until the Cortes of Cádiz could be convened.

Establishment

On 18 April 1810, agents of the Spanish Regency arrived in the city of Caracas. After considerable political tumult, the local nobility announced an extraordinary open hearing of the cabildo (the municipal council), set for the morning of 19 April, Maundy Thursday. On that day, an expanded municipal government of Caracas took power in the name of Ferdinand VII, calling itself The Supreme Junta to Preserve the Rights of Ferdinand VII (La Suprema Junta Conservadora de los Derechos de Fernando VII) and consequently deposed Captain General Vicente Emparán and other colonial officials.

This initiated a process that would lead to a declaration of independence from Spain. Soon after 19 April, many other Venezuelan provinces also established juntas, most of which recognized the Caracas one (though a few recognized both the Regency in Spain and the Junta in Caracas). Still other regions never established juntas, but rather kept their established authorities and continued to recognize the government in Spain. This situation consequently led to a civil war between Venezuelans who were in favor of the new autonomous juntas and those still loyal to the Spanish Crown. The Caracas Junta called for the convention of a congress of the Venezuelan provinces which began meeting the following March, at which time the Junta dissolved itself. The Congress set up a triumvirate to handle the executive functions of the union .

Shortly after the juntas were set up, Venezuelan émigré Francisco de Miranda had returned to his homeland taking advantage of the rapidly changing political climate. He had been a persona non grata since his failed attempt at liberating Venezuela in 1806. Miranda was elected to the Congress and began agitating for independence, gathered around him a group of similarly-minded individuals, who formed an association, modeled on the Jacobin Club, to pressure the Congress. Independence was formally declared on 5 July 1811.[2] The Congress established a Confederation called the American Confederation of Venezuela in its Declaration of Independence, referred variously as States of Venezuela (in its opening sentence) and afterwards United States of Venezuela, and American Confederation of Venezuela in the Constitution, crafted mostly by lawyer Juan Germán Roscio, that it ratified on 21 December 1811. The Constitution created a strong bicameral legislature and, as also happened in neighboring New Granada, the Congress kept the weak executive consisting of a triumvirate.[3] This government was not in force for long, since the provinces (referred to as states in the Constitution) did not fully implement it.[4] The provinces also wrote their own constitutions, a right which the Congress recognized.

Civil War and disestablishment

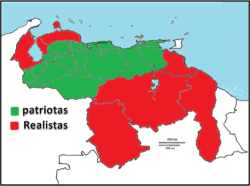

Though the Congress declared independence, the provinces of Maracaibo and Guayana and the district of Coro remained loyal to the Supreme Central Junta of Spain (1808–10) and the Cortes of Cádiz that followed it. The new Confederation claimed the right to govern the territory of the former Captaincy General, and the region plunged into full civil war by 1810 with fighting breaking out between royalist and republican areas. A military expedition from Caracas to bring Coro back under its control, was defeated in November. The Caracas Junta, which continued to govern Caracas Province, did not have much power in the newly declared Confederation, and had a hard time getting supplies and reinforcements from the other confederated provinces. The Confederation was led by criollos, but was not able to appeal to the lower classes, despite attempts to do so, because of a declining economic situation. Cut off from Spain, Venezuela lost the market for its main export, cocoa. As a result, Venezuela experienced severe losses of specie, using it to purchase much needed supplies from its new trading partners, such as the British and the Americans, which could not take the full output of agricultural products as payment. The federal government resorted to printing paper money to pay its debts with Venezuelans, but the paper money rapidly lost value, turning many against the government.

In 1812 the Confederation began suffering serious military reverses, and the government granted Miranda command of the army and leadership of the Confederation. A powerful earthquake, which hit Venezuela on 26 March 1812, also a Maundy Thursday, and caused damage mostly in republican areas, also helped turn the population against the Republic. Since, the Caracas Junta had been established on a Maundy Thursday, the earthquake fell on its second anniversary in the liturgical calendar. This was interpreted by many as a sign from Providence, and many, including those in the Republican army, began to secretly plot against the Republic or outright defect.[5][6][7] Other provinces refused to send reinforcements to Caracas Province. Worse still, whole provinces began to switch sides. On 4 July an uprising brought Barcelona over to the royalist side. Neighboring Cumaná, now cut off from the Republican center, refused to recognize Miranda's dictatorial powers and his appointment of a commandant general. By the middle of the month many of the outlying areas of Cumaná Province had also defected to the royalists.

Taking advantage of these circumstances a Spanish marine frigate captain, Domingo Monteverde, based in Coro, was able to turn a small force under his command into a large army, as people joined him on his advance towards Valencia. Miranda was left in charge of only a small area of central Venezuela.[8] In these dire circumstances the republican government had appointed Miranda generalissimo, with broad political powers. By mid-July Monteverde had taken Valencia, and Miranda thought the situation was hopeless and started negotiations with Monteverde. On 25 July 1812 Miranda and Monteverde finalized a capitulation in which the former republican areas would recognize the Cortes of Cádiz. The First Republic had come to an end. Monteverde's forces entered Caracas on 1 August.

Provinces

- Mérida Province

- Trujillo Province

- Caracas Province

- Barinas Province

- Barcelona Province

- Cumaná Province

- Margarita Province

See also

References

- McKingley, 150–154.

- In Spanish: Venezuelan Declaration of Independence, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes

- In Spanish: Federal Constitution of 1811 Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. A bicameral General Congress consisting of Senate and House of Representatives was the nation's legislature provided in the document. The Constitution uses Confederación de Venezuela and los Estados Unidos de Venezuela interchangeably, while referring to the establishment of "Estados de Venezuela" in its preamble.

- Parra-Pérez, Primera República, Vol. 2, 108–109.

- Masur, Gerhard (1948). Simon Bolivar. Alburquerque: University of New Mexico. pp. 133–137.

- Morón, Guillermo (1963). A History of Venezuela. New York: Roy Publishers. p. 109.

- Lynch, John (2006). Simón Bolívar: A Life. New Haven: Yale University. pp. 59, 61. ISBN 0-300-11062-6.

- Parra-Pérez, Caracciolo. Primera República, Vol. 2, 357–365.

Bibliography

In English:

- Lynch, John. The Spanish American Revolutions, 1808–1821, 2nd ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 1986. ISBN 0-393-09411-1

- McKingley, P. Michael. Pre-Revolutionary Caracas: Politics, Economy, and Society, 1777–1811. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-521-30450-4

- Rodríguez O., Jaime E. The Independence of Spanish America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-62673-0

- Stoan, Stephen K. Pablo Morillo and Venezuela, 1815–1820. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1959.

In Spanish:

- Fundación Polar. "Primera República", Diccionario de Historia de Venezuela, Vol. 3. Caracas: Fundacíon Polar, 1997. ISBN 980-6397-37-1

- Parra-Pérez, Caracciolo. Historia de la Primera República de Venezuela. Caracas: Biblioteca de la Academia Nacional de la Historia,1959.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)