Great Sortie of Stralsund

The Great Sortie of Stralsund (Swedish: Stora utfallet från Stralsund) was fought in the Franco-Swedish War (part of the War of the Fourth Coalition) on 1–3 April 1807, in Swedish Pomerania (present-day Germany). A French army under Édouard Mortier invaded Swedish Pomerania in early 1807 and initiated a blockade of the Swedish town of Stralsund, to secure the French rear from enemy attacks. After several smaller sorties and skirmishes around Stralsund, Mortier marched part of his army to support the ongoing Siege of Kolberg, leaving only a smaller force under Charles Louis Dieudonné Grandjean to keep the Swedes at check. The Swedish commander Hans Henric von Essen then commenced a great sortie to push the remaining French forces out of Swedish Pomerania. The French fought bravely on 1 April at Lüssow, Lüdershagen and Voigdehagen, but were eventually forced to withdraw; the Swedes captured Greifswald the next day, after a brief confrontation. The last day of fighting occurred at Demmin and Anklam, where the Swedes took many French prisoners of war, resulting in the complete French withdrawal out of Swedish Pomerania—while the Swedes continued their offensive into Prussia. After two weeks Mortier returned and pushed the Swedish forces back into Swedish Pomerania. After an armistice the French forces once again invaded, on 13 July, and laid siege to Stralsund, which they captured on 20 August; all of Swedish Pomerania was captured by 7 September, but the war between Sweden and France continued until January 6 1810, when the Swedes were finally forced to sign the Treaty of Paris.

| Great Sortie of Stralsund | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Swedish War and the War of the Fourth Coalition | |||||||

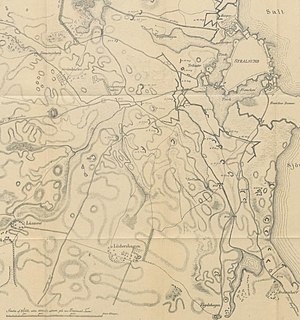

Stralsund and nearabouts (Lüssow, Lüdershagen and Voigdehagen; bottom), by O.W. Smith | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000–6,000[1] | 5,700[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,300 killed, wounded or captured[3] | 100 killed or wounded[4] | ||||||

Background

Because of his hate towards Napoleon, the Swedish king Gustav IV Adolf declared war on France—against the advice of his counsellors—and entered the War of the Third Coalition, on 31 October 1805; after having remained neutral for several years since the events of the French Revolution.[5] The first year of war turned out to be a major disappointment for the Swedes, as only half-hearted attempts were made by the Swedish king to advance his positions, combined with several decisive defeats for his allies.[6] Further setbacks occurred in late 1806, during the War of the Fourth Coalition, as 1,000 unarmed Swedish soldiers were forced into captivity in the Battle of Lübeck, as they were caught in the process of shipping away towards Stralsund.[7] In the beginning of 1807, as the Swedes under Hans Henric von Essen remained passive within Swedish Pomerania, a French army under Édouard Mortier crossed the Swedish border with 12,000 men,[8] and subsequently initiated a blockade of Stralsund on January 30, after some Swedish resistance.[7] The Swedes had about 13,000 men in Stralsund and on the vital island of Rügen, including 3,000 landwehr.[8]

After several skirmishes with shifting luck,[9] and as the French numbers quickly dwindled down as they were needed at the Siege of Kolberg—while the Swedish force progressively received reinforcements[10]—the Swedes started planning for a break out by the way of a great sortie.[11] As Mortier quit Stralsund with the bulk of the French army he left a 5,000–6,000 strong division, under Charles Louis Dieudonné Grandjean, to oppose the Swedes.[1] Grandjean, however, soon also sought to leave with the rest of his troops. For this reason he requested a cease-fire, informing Essen of his intention to leave Swedish Pomerania on the condition that the withdrawal would proceed unhindered; it would not be regarded, he noted, as if he had been forced to leave, as a rumoured military defeat could weaken the diplomatic state of France.[12]

Battles

Essen disregarded the request and instead, on 31 March, prepared his army for a great sortie by splitting it into two columns; the right column, led by Tawast with Essen himself in command, would encircle the left flank of the French forces—it consisted of one battlion each from the Uppland, Jönköping, Dalarna and the Queen's regiments, with six squadrons from the Mörnerian Hussars and four guns, in all 2,500 men; the left column, led by Eberhard von Vegesack with Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt in command, would attack the French center—it consisted of one battalion each from the Skaraborg, Södermanland, Västgöta-Dals, Närke-Värmland and Engelbrecht regiments with one squadron hussars and nine guns, in all 2,300 men. Two battalions of the Bohuslän and Västmanland regiments, in all 900 men with two guns under Cardell, were also left inside Stralsund as reserve.[2]

April 1 (Lüdershagen–Voigdehagen)

The two Swedish columns moved out on 1 April, with Jäger-chains covering their advance;[13] the right column under Essen broke out at 7:00 towards the French redoubt at Kettenhagen, which had been abandoned, while the French forces opposite the Swedish column quickly withdrew. Next Groß Kordshagen was captured, followed by Born and Pütte, where the Swedes took a French magazine, before reaching Langendorf. Meanwhile, the left Swedish column under Armfelt marched out at 8:00 and beat the French from Garpenhagen, Grünhof as well as the battery infront of Langendorf, where the two columns then regrouped.[14]

Next Lüssow was attacked, which was defended by a couple of hundred French soldiers; only after combined Swedish assaults from both front and flanks, with the support of artillery, could they be beaten back towards Lüdershagen. Here—because of strong fortifications and French reinforcements—an even stronger resistance was offered resulting in several attacks, by Armfelt, being repelled.[15][13] The French were soon, however, forced to retire as further Swedish reinforcements arrived from Essen's column and jointly stormed the village. The French once again took a stand, this time at the heights of Voigdehagen, where an equally fierce battle ensued which would last for an hour.[16][15]

Meanwhile, a small Swedish detachment under Tawast had been sent out from Essen's column to march southwards, towards Wendorf, to cut-off the French retreat. They got intercepted by strong French forces which came through the forest, between Wendorf and Voigdehagen, with the support of four cannons and two howitzers behind the latter. The French fire got so intense that the Swedish infantry was ordered to go prone in the field while two of their own guns cleared the forest with canister shot. Tawast then attacked the French battery which, combined with the assaults made by Armfelt further to the north, forced the French to retreat from Voigdehagen.[15]

The Swedish reserve force, under Cardell, had simultaneously operated in the French right flank; he had repelled a French cavalry attack near Stralsund, after which he successfully assaulted the fortified Hohengraben,[17] followed by Andershof, where the French suffered considerable losses to a Swedish gunboat division.[18] After continuous fighting for several hours the exhausted Swedish left and right columns spent the night at Arendsee and Elmenhorst, respectively. The main French army had retreated to Greifswald during the day, while the baggage train went through Grimmen, all the way to Demmin.[17]

April 2 (Greifswald)

Early the next day the Swedish columns continued their march in persecution of the French army; Tawast, with the right column, marched through Glimmen towards Loitz, where he arrived at 18:00 and struck camp for the night. As Armfelt broke camp he separated his force into two individual columns; a left one was led by Cardell and marched on the main road towards Greifswald, while the right column, under Vegesack, marched through Petershagen—Levenhagen—Ungnade, to fall into the rear of the retreating French forces. As a Swedish negotiator with escort approached Greifswald, to ask for their surrender, the French forces panicked and ran; the few hussars in the escort then chased after, into the town, where they made several prisoners.[19]

The French forces soon rallied behind the town and counterattacked; the Swedish commander Armfelt got close to being captured in the ensuing struggle. However, as more Swedish troops arrived, the French positions got overwhelmed and they were in-turn thrown back towards Koitenhagen.[19] Three divisions of Swedish gunboats also attacked the village of Wiek, just outside Greifswald, and completely destroyed the sconce there.[18] Cardell and his column, who gained a notable war trophy in Greifswald, spent the night in the town, along with Armfelt; Vegesack's column stayed at Dersekow.[19]

April 3 (Demmin–Anklam)

The right column, led by Tawast with Essen in command, continued their march from Loitz 8:00 in the morning to intercept the French baggage train, protected by 800 men, at Demmin. As the hussars of the advance guard arrived they immediately charged through the gates—which had been left open—and into the town, where 129 French soldiers were made prisoners. The French forces retreated towards Mecklenburg, with the enemy hot on their heels; four Swedish hussars captured 104 French soldiers on the road leading to Neukalen; 168 men were captured at Dargun by a Swedish squadron, along with rich spoils of war; a French baggage train along with 209 men from the 72nd Infantry Regiment was captured at Krukow, by a mere 42 hussars under Bror Cederström (famous from the Battle of Bornhöved) and Krassow.[20][21]

In the morning Armfelt also broke camp with his two left-columns; Vegsack marched towards Lüssow (Gützkow) and Cardell towards Ziethen and Anklam, where he arrived on the evening, after having crossed the border to Prussia. Armfelt commenced an attack on the suburb with his jägers—without the planned support of the Swedish gunboats—with success; the Swedish jägers traversed the marsh on the sides and, after an hour of musket exchange, forced the defenders to retreat across the Peene and into the town of Anklam itself. The Swedes were unable to repair the bridge, which had been ruined by the retreating French, due to the accurate fire they received from across the river.[22]

After a few hours of insignificant firefight, Cardell, with 50 men from the Västmanland Regiment, crossed the river in a pram and launched a surprising bayonet charge which forced the French away from the bridge. While Cardell pursued the baggage train of the fleeing enemy just outside the town, more Swedes made it over and joined the fight; the French force soon routed without offering much of a resistance, leaving the train along with 167 men in the hands of the Swedes. Armfelt's other column, under Vegesack, had reached Jarmen by this time;[22] Swedish Pomerania, as well as the Prussian islands of Usedom and Wolin,[3] had thus been cleared from French troops as the Swedish columns now stood on Prussian soil.[23] Grandjean and the remaining French forces retreated to Stettin.[3]

Aftermath

The Swedish casualties during the three days of fighting had been low; the left column under Armfelt had lost only 15 men killed and 33 wounded, while the casualties for the right column under Essen are unknown, but few. The losses for the French forces are uncertain; the Swedes had captured at least 1,000 men,[4] or, according to other sources, 1,800 men; with 564 men captured by Essen and 1,245 by Armfelt (including the reserve column).[24] The Swedish king created a Régiment du Roi from captured French soldiers.[25] The war trophy captured by the Swedes had been worth more than 300,000 riksdaler banco,[4] excluding the material captured on Usedom and Wolin, which the French had abandoned during their hasty retreat.[1] News of the Swedish victory in Pomerania arrived on the night between 5–6 April to Malmö and were received with big celebrations in Sweden.[4] As predicted by Grandjean, the news of their defeat produced a certain alarm in the rear of the French army; especially in Berlin, where an humbled enemy "sought food for its hopes".[1]

The Swedish offensive continued for some days as a small commando sneaked into Rostock, on 6 April, and opened the gates for the remaining Swedish force which stood outside ready to storm; the town was captured, along two guns and 148 men of its' garrison.[26] Ueckermünde was captured on the same day by a combined Swedish naval and land offensive. The town of Schwerin was likewise captured the next day, as 100 Swedes attacked the garrison of 200 men and, after intense fighting, made 47 of them prisoners—with only one killed and two wounded themselves. This was followed up by the capture of Wolin on the 10th, while an additional 65 French soldiers were captured two days later at Jasenitz, against two killed and three wounded Swedes.[27][28] The Swedish right flank under Tawast remained in a defensive stance at Demmin while the left, under Armfelt, advanced as far as to the Uecker—instead of withdrawing to a more advantageous position behind the Peene; this resulted in an overextended Swedish defense line with inadequate communication. Armfelt explicated the “tenacity and courage of the Swedish soldier” as a reason for his advanced position, in his after action report.[29]

French retaliation did not wait as 13,000 men under Mortier arrived from Kolberg and defeated the Swedish left flank on 16 April,[3] at the Battle of Belling; the 2,000 Swedes under Vegesack commenced a fighting retreat,[30] to Anklam and across the Peene. The Swedish retreat left a thousand men under Cardell cut-off at Ueckermünde, where 694 of them were made prisoners. An armistice was signed at Schmatzin on 18 April, initiated by Essen, resulting in the withdrawal of all remaining Swedish troops into Swedish Pomerania.[31] The Swedish king denounced the armistice on 3 July, with a 10-days notice; by this time, however, the Treaties of Tilsit had just deprived Sweden of all her allies but the United Kingdom.[32]

A French army under Guillaume Brune crossed the Swedish border on 13 July with 40,000–50,000 men and, after two days of hopeless Swedish resistance, initiated a Siege of Stralsund.[32][33] Stralsund was captured on 20 August, as the Swedes transferred their forces to the island of Rügen. On 25 August the Swedish island of Dänholm was captured,[34] after which the Swedish troops were allowed free departure to Sweden—thus having left all of Swedish Pomerania in French hands by 7 September. Sweden was ultimately forced to surrender on 6 January 1810 and enter the Continental System, after having suffered a Russian invasion from the east, as well as a Danish attack from the west.[35]

References

- Thiers 1849, p. 283.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 162–163.

- Sundberg 2010, p. 312.

- Björlin 1882, p. 174.

- Sundberg 2010, p. 306.

- Sundberg 2010, pp. 309–310.

- Sundberg 2010, p. 311.

- Björlin 1882, p. 137.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 146–158.

- Björlin 1882, p. 159.

- Sundberg 2010, pp. 306–312.

- Björlin 1882, p. 160.

- Vegesack 1840, p. 44.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 163–164.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 165–167.

- Vegesack 1840, pp. 44–45.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 168–169.

- Björlin 1882, p. 177.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 169–170.

- Philström & Westerlund 1911, pp. 160–161.

- Björlin 1882, p. 171.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 172–173.

- Vegesack 1840, pp. 45–46.

- Vegesack 1850, pp. 58–59.

- Vegesack 1840, p. 67.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 175–176.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 178–179.

- Vegesack 1840, pp. 46–47.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 181–182.

- Vegesack 1850, pp. 60–62.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 189–193.

- Sundberg 2010, p. 313.

- Björlin 1882, pp. 204–214.

- Sundberg 2010, p. 314.

- Sundberg 2010, p. 315.

Sources

- Björlin, Gustaf (1882). Sveriges krig i Tyskland åren 1805–1807 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Militärlitteratúr-Föreningens förlag.

- Sundberg, Ulf (2010). Sveriges krig: 1630–1814, Part 3 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Svenskt militärhistoriskt bibliotek.

- Vegesack, Ernst von (1840). Svenska arméens fälttåg uti Tyskland och Norrige åren 1805, 1806, 1807 och 1808 (in Swedish). Stockholm: L.J. Hjerta.

- Vegesack, Eugène von (1850). Anteckningar öfver Svenska furstliga personer samt officerare m. fl (in Swedish). Stockholm: N. Marcus.

- Thiers, Adolphe (1849). History of the Consulate and the Empire of France Under Napoleon, Volume 2. Philadelphia: Cary & Hart.

- Philström, Anton; Westerlund, Carl (1911). Kungl. Dalregementets Historia. 5:te Afdelningen (in Swedish). Stockholm: Kungl. Boktryckeriet. P. A. Norstedt & Söner.

.jpg)

.tiff.jpg)