Campaign in south-west France (1814)

The campaign in south-west France in late 1813 and early 1814 was the final campaign of the Peninsular War. An allied army of British, Portuguese and Spanish soldiers under the command of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington fought a string of battles against French forces under the command of Marshal Jean de Dieu Soult, from the Iberian Peninsula across the Pyrenees and into south-west France ending with the capture of Toulouse and the besieging of Bayonne.

| Campaign in south-west France | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peninsular War | |||||||

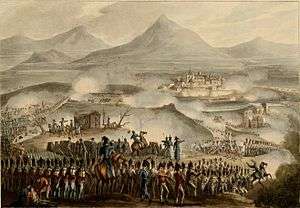

The Battle of Toulouse | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The campaign ended when—on receiving word of the abdication of Napoleon Bonaparte as Emperor of France, and the ratification of a general armistice (the Treaty of Fontainebleau, 11 April)—the opposing commanders signed a local armistice on 17 April 1814.

Prelude (end of the war in Spain, 1813–1814)

Campaign in the eastern Atlantic region

In July 1813 Marshal Soult began a counter-offensive (the Battle of the Pyrenees) and defeated the Allies at the Battle of Maya and the Battle of Roncesvalles (25 July). Pushing on into Spain, by 27 July the Roncesvalles wing of Soult's army was within ten miles of Pamplona but found its way blocked by a substantial allied force posted on a high ridge in between the villages of Sorauren and Zabaldica, lost momentum, and was repulsed by the Allies at the Battle of Sorauren (28 and 30 July)[1] Reille's right wing suffered further losses at Yanzi (1 August); and the Echallar and Ivantelly (2 August) during its retreat into France.[2][3][4] Total losses during this counter-offensive being about 7,000 for the Allies and 10,000 for the French.[2]

In August 1813, British headquarters still had misgivings about the eastern powers. Austria had now joined the Allies, but the Allied armies had suffered a significant defeat at the Battle of Dresden. They had recovered somewhat, but the situation was still precarious. Wellington's brother-in-law Edward Pakenham wrote, "I should think that much must depend upon proceedings in the north: I begin to apprehend ... that Boney may avail himself of the jealousy of the Allies to the material injury of the cause."[5] But the defeat or defection of Austria, Russia and Prussia was not the only danger. It was also uncertain that Wellington could continue to count on Spanish support.[6]

On 8 September Wellington accepted the surrender of the French-garrisoned city of San Sebastián under Brigadier-General Louis Emmanuel Rey after two sieges that lasted from 7 July to 25 July (While Wellington departed with sufficient forces to deal with Marshal Soult's counter-offensive, he left General Graham in command of sufficient forces to prevent sorties from the city and any relief getting in. Wellington next determined to throw his left across the river Bidassoa to strengthen his own position, and secure the port of Fuenterrabia.[2]

At daylight on 7 October 1813 Wellington crossed the Bidassoa in seven columns, attacked the entire French position, which stretched in two heavily entrenched lines from north of the Irun-Bayonne road, along mountain spurs to the Great Rhune 2,800 feet (850 m) high.[7] The decisive movement was a passage in strength near Fuenterrabia to the astonishment of the enemy, who in view of the width of the river and the shifting sands, had thought the crossing impossible at that point. The French right was then rolled back, and Soult was unable to reinforce his right in time to retrieve the day. His works fell in succession after hard fighting, and he withdrew towards the river Nivelle.[8] The losses were about—Allies, 800; French, 1,600.[9] The passage of the Bidassoa "was a general's not a soldier's battle".[10][8]

On 31 October Pamplona surrendered, and Wellington was now anxious to drive Marshal Suchet from Catalonia before invading France. The British government, however, in the interests of the continental powers, urged an immediate advance over the northern Pyrenees into south-western France.[2] Napoleon had just suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Leipzig on 19 October and was in retreat, so Wellington left the clearance of Catalonia to others.[2]

Campaign in the northern Mediterranean region

After the Battle of Vitoria (21 June 1813) Marshal Suchet, evacuated Tarragona (17 August) but defeated Bentinck in the battle of Ordal (13 September).[8]

Although there were a few minor battles during 1814 (notably Battle of Molins de Rey on 16 January), Suchet's army was repeatedly denuded of regiments sent to reinforce the French forces fighting in the north-east France theatre. As his army shrank, Suchet was able to keep a small field force in being by calling in outlying garrisons (that were not besieged by the Allies) and gradually moving his area of operations closer to the French frontier (so shortening his lines of communication and adding the men previously guarding them to his field force). At the end of the campaign in early April 1814 Suchet had about 14,000 men cantonmented around the Spanish frontier town of Figueras. Some besieged fortresses and towns also held out to the end of the war (notably Barcelona under the command of the French General Pierre-Joseph Habert who attempted two major sorties before eventually surrendering on 25 April).[11]

Towards the end of the campaign the Allies underestimated the size of Suchet's force and thought that Suchet with the remnant of his army was crossing the Pyrenees to join Soult in the Atlantic theatre. So the Allies started to redeploy their own forces. The best of the British forces in Catalonia were ordered to join Wellington's army on the river Garonne in France.[lower-alpha 2] They left to do so on 31 March, leaving the Spanish to mop up the remaining French garrisons in Catalonia.[12] Consequently, when Wellington agreed an armistice with Marshal Soult, he included Suchet's forces in that armistice, although Suchet and his small army were still on the Spanish side of the Pyrenees.[13]

Invasion of France

Battle of the Nivelle, November 1813

On the night of 9 November 1813 Wellington brought up his right from the Pyrenean passes to the northward of Maya and towards the Nivelle. Marshal Soult's army (about 79,000), in three entrenched lines, stretched from the sea in front of Saint-Jean-de-Luz along commanding ground to Amotz and thence, behind the river, to Mont Mondarrain near the Nive.[8]

Each army had with it about 100 guns; and, during a heavy cannonade, Wellington on 10 November 1813 attacked this extended position of 16 miles (26 km) in five columns, these being so directed that after carrying Soult's advanced works a mass of about 50,000 men converged towards the French centre near Amotz, where, after hard fighting, it swept away the 18,000 of the second line there opposed to it, cutting Soult's army in two. The French right then fell back to Saint-Jean-de-Luz, the left towards points on the Nive. It was now late and the Allies, after moving a few miles down both banks of the Nivelle, bivouacked, while Soult, taking advantage of the respite, withdrew in the night to Bayonne. The allied loss during the Battle of Nivelle was about 2,700; that of the French 4,000, 51 guns, and all their magazines. The next day Wellington closed in upon Bayonne from the sea to the left bank of the Nive.[8]

Battles of the Nive, December 1813

After this there was a period of comparative inaction, though during it the French were driven from the bridges at Urdains[lower-alpha 3] and Cambo-les-Bains.[lower-alpha 4] The weather had become bad, and the Nive unfordable; but there were additional and serious causes of delay. The Portuguese and Spanish authorities were neglecting the payment and supply of their troops. Wellington had also difficulties of a similar kind with his own government, and also the Spanish soldiers, in revenge for many French outrages, had become guilty of grave excesses in France, so that Wellington took the extreme step of sending 25,000 of them back to Spain and resigning the command of their army (though his resignation was subsequently withdrawn). So great was the tension at this crisis that a rupture with Spain seemed possible, but this did not happen.[8][lower-alpha 5]

Wellington, who in his cramped position between the sea and the Nive could not use his cavalry or artillery effectively, or interfere with the French supplies coming through Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port, determined to occupy the right as well as the left bank of the Nive. He could not pass to that bank with his whole force while Soult held Bayonne, without exposing his own communications through Irun. Therefore, on 9 December 1813, after making a demonstration elsewhere, he effected the passage with a portion of his force only under Rowland Hill and Beresford, Ustaritz and Cambo-les-Bains, his loss being slight, and thence pushed down the river towards Villefranque, where Soult barred his way across the road to Bayonne. The allied army was now divided into two portions by the Nive; and Soult from Bayonne at once took advantage of his central position to attack it with all his available force, first on the left bank and then on the right.[8]

On the morning of 10 December with 60,000 men and 40 guns, he attacked Hope, who with 30,000 men and 24 guns held a position from the sea 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Biarritz on a ridge behind two lakes (or tanks) through Arcangues towards the Nive. Desperate fighting now ensued, but fortunately for the British, owing to the intersected ground, Soult was compelled to advance slowly, and in the end, Wellington coming up with Beresford from the right bank, the French retired baffled.[8]

On 11 and 12 December there were engagements of a less severe character, and finally on 13 December Soult with 35,000 men made a vehement attack up the right bank of the Nive against Hill, who with about 14,000 men occupied some heights from Villefranque past Saint-Pierre (Lostenia) to Vieux Mouguerre.[lower-alpha 6] The conflict about Saint-Pierre (Lostenia) was one of the most bloody of the war; but for hours Hill maintained his ground, and finally repulsed the French before Wellington, delayed by his pontoon bridge over the Nive having been swept away, arrived to his aid. The losses in the four days' fighting in the battles before Bayonne (or battles of the Nive) were-Allies about 5,000, French about 7,000.[8][lower-alpha 7]

Battle of Garris, February 1814

When operations recommenced in February 1814 the French line extended from Bayonne up the north bank of the Adour to the Pau, thence bending south along the Bidouze to Saint-Palais, with advanced posts on the Joyeuse and at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. Wellington's left, under Hope, watched Bayonne, while Beresford, with Hill, observed the Adour and the Joyeuse, the right trending back until it reached Urcuray on the Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port road.[8]

Exclusive of the garrison of Bayonne and other places, the available field force of Soult numbered about 41,000, while that of the Allies, deducting Hope's force observing Bayonne, was of much the same strength. It had now become Wellington's object to draw Soult away from Bayonne so that the allied army, with fewer losses, might cross the Adour and lay siege to the place on both banks of the river.[8]

At its mouth the Adour was about 500 yards (460 m) wide, and its entrance from the sea by small vessels, except in the finest weather, was a perilous undertaking, owing to the shifting sands and a dangerous bar. On the other hand, the deep sandy soil near its banks made the transport of bridging matériel by land laborious, and almost certain of discovery. Wellington, convinced that no effort to bridge below Bayonne would be expected, decided to attempt it there, and collected at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port and Passages a large number of country vessels (termed chasse-marées) Then, leaving Hope with 30,000 men to watch Bayonne, he began an enveloping movement round Soult's left. Hill on 14 and 15 February, after a battle of Garris, drove the French posts beyond the Joyeuse; and Wellington then pressed these troops back over the Bidouze and Gave de Mauleon to the Gave d'Oloron.[lower-alpha 8] Wellington's object in this was at once attained, for Soult, leaving only 10,000 men in Bayonne, came out and concentrated at Orthez on the Pau. Then Wellington (19 February) proceeded to Saint-Jean-de-Luz to superintend the despatch of boats to the Adour. Unfavourable weather, however, compelled him to leave this to Sir John Hope and Admiral Penrose, so returning to the Gave d'Oloron he crossed it, and faced Soult on the Pau (25 February).[8][lower-alpha 9]

Passage of the Adour, February 1814

Hope in the meantime, after feints higher up the Adour, succeeded (22 and 23 February) in passing 600 men across the river in boats. The nature of the ground, and there being no suspicion of an attempt at this point, led to the French coming out very tardily to oppose them; and when they did, some Congreve Rockets (then a novelty) threw them into confusion, so that the right bank was held until, on the morning of 24 February, the flotilla of chasse-marées appeared from Saint-Jean-de-Luz, preceded by men-of-war boats. Several men and vessels were lost in crossing the bar, but by noon on 26 February the bridge of 26 vessels had been thrown and secured, batteries and a boom placed to protect it, 8,000 troops passed over, and the enemy's gunboats driven up the river. Bayonne was then invested on both banks as a preliminary to the siege.[16]

Battle of Orthez, February 1814

On 27 February, Wellington, having with little loss effected the passage of the Pau below Orthez, attacked Soult. At the Battle of Orthez the Allies and French were of about equal strength (37,000): the former having 48 guns, the latter 40. Soult held a strong position behind Orthez on heights commanding the roads to Dax and Saint-Sever. Beresford was directed to turn his right, if possible cutting him off from Dax, and Hill his left towards the Saint-Sever road. Beresford's attack, after hard fighting over difficult ground, was repulsed, when Wellington, perceiving that the pursuing French had left a central part of the heights unoccupied, thrust up the Light Division into it, between Soult's right and centre. At the same time Hill, having found a ford above Orthez, was turning the French left, when Soult retreated just in time to save being cut off, withdrawing towards Saint-Sever, which he reached on 28 February. The allied loss was about 2,000; the French 4,000 and 6 guns.[17]

Action at Tarbes, March 1814

From Saint-Sever Soult turned eastwards to Aire-sur-l'Adour, where he covered the roads to Bordeaux and Toulouse. Beresford, with 12,000 men, was now sent to Bordeaux, which opened its gates as promised to the Allies. Driven by Hill from Aire-sur-l'Adour on 2 March 1814, Soult retired by Vic-en-Bigorre, where there was a combat (19 March), and Tarbes, where there was a severe action (20 March), to Toulouse behind the Garonne. He endeavoured also to rouse the French peasantry against the Allies, but in vain, for Wellington's justice and moderation afforded them no grievances.[17][18]

Wellington wished to pass the Garonne above Toulouse in order to attack the city from the south—its weakest side—and interpose between Soult and Suchet. But finding it impracticable to operate in that direction, he left Hill on the west side and crossed at Grenade below Toulouse (3 April).[17]

Battle of Toulouse, April 1814

When Beresford, who had now rejoined Wellington, had passed over, the bridge was swept away, which left him isolated on the right bank. But Soult did not attack, and the bridge as restored on 8 April, Wellington crossed the Garonne and the Hers-Mort,[lower-alpha 10] and attacked Soult on 10 April. In the battle of Toulouse the French numbered about 40,000 (exclusive of the local National Guards) with 80 guns; the Allies under 52,000 with 64 guns. Soult's position to the north and east of the city was exceedingly strong, consisting of the Canal du Midi, some fortified suburbs, and (to the extreme east) the commanding ridge of Mont Rave (Heights of Calvinet), which crowned the redoubts and earthworks. Wellington's columns, under Beresford, were now called upon to make a flank march of some two miles, under artillery, and occasionally musketry, fire, being threatened also by cavalry, and then, while the Spanish troops assaulted the north of the ridge, to wheel up, mount the eastern slope, and carry the works. The Spaniards were repulsed, but Beresford's forces took Mont Rave and Soult fell back behind the canal.[17]

On 12 April Wellington advanced to invade Toulouse from the south, but Soult on the night of 11 April had retreated towards Villefranque, and Wellington then entered the city. The allied loss was about 5,000, the French 3,000. Thus, in the last great battle of the war, the courage and resolution of the soldiers of the Peninsular army were conspicuously illustrated.[17]

On 13 April 1814 officers arrived with the announcement to both armies of the capture of Paris, the abdication of Napoleon, and the practical conclusion of peace; and on 18 April a convention, which included Suchet's force, was entered into between Wellington and Soult.[17]

Unfortunately, after Toulouse had fallen, the Allies and French, in a sortie from Bayonne on 14 April, each lost about 1,000 men, so that some 10,000 men fell after peace had virtually been made.[17] The Peace of Paris was formally signed on 30 May 1814.[17]

Aftermath

At the end of the campaign, British troops were partly sent to England, and partly embarked at Bordeaux for America for service in the final months of the American War of 1812. The Portuguese and Spanish recrossed the Pyrenees and the French army dispersed throughout France. Louis XVIII was restored to the French throne; and Napoleon was permitted to reside on the island of Elba, the sovereignty of which had been conceded to him by the allied powers.

Notes

- The fighting on the south-western front continued for several days after signing of the Treaty of Fontainebleau (11 April 1814) an armistice on the north-eastern front, and a precursor to general peace (Treaty of Paris signed on 30 May 1814)

- The Anglo-Italian battalions, the Calabrians and the Sicilian "Estero" regiment were sent to Sicily (Oman 1930, p. 429).

- The bridge crosses the Urdains brook (a tributary of the Nive) just north of the Château d'Urdain.

- George Bell, then a junior British officer in the 34th Foot recounted in his biography that the period of inaction in this area of an "Irish sentry who was found with a French and an English musket on his two shoulders, guarding a bridge over a brook on behalf of both armies. For he explained to the officer going the rounds that his French neighbour had gone off on his behalf, with his last precious half-dollar, to buy brandy for both, and had left his musket in pledge till his return. The French officer going his rounds on the other side of the brook then turned up, and explained that he had caught his sentry, without arms and carrying two bottles, a long way to the rear. If either of them reported what had happened to their colonels, both sentries would be court-martialled and shot. Wherefore both subalterns agreed to hush up the matter".[14]

- On 11 December, Napoleon, beleaguered and desperate, agreed to a separate peace with Spain under the Treaty of Valençay, under which he would release and recognize Ferdinand in exchange for a complete cessation of hostilities. But the Spanish had no intention of trusting Napoleon and the fighting continued.

- "Vieux Mouguerre" is spelt "Vieux Moguerre" in some sources.[8]

- On the evening of 10 December, some 1,400 troops from three German battalions deserted in response to a secret message from the Duke of Nassau—one of the many German rulers who had surrendered following the Battle of Leipzig—ordering them to surrender to the Allies. In addition, Soult and Suchet lost the rest of their German units—another 3,000 men—as it was felt that they became unreliable. This left the Adour's defenders much depleted and incapable of further offensive action.[15]

- "Gave" in the Pyrenees means a mountain stream or torrent.[8]

- in some sources Orthez is spelt Orthes.[8]

- Contemporary British military sources and some secondary sources call this river the "Ers" (Robinson 1911, p. 97).

- Esdaile 2003, p. 462.

- Robinson 1911, p. 95.

- COS staff (November 2014), Battle Name:Yanzi, clash-of-steel.com.

- Napier 1879, pp. 321–325.

- Pakenham, Edward Michael; Pakenham Longford, Thomas (2009). Pakenham Letters: 1800–1815. Ken Trotman Publishing. p. 221.

- Esdaile 2003, p. 455.

- Robinson 1911, pp. 95–96.

- Robinson 1911, p. 96.

- Oman 1930, pp. 535, 536.

- Napier 1879, p. 367.

- Oman 1930, pp. 308-311, 402, 406, 411-415, 431-432, 459, 500.

- Oman 1930, p. 431.

- Oman 1930, pp. 431-432.

- (Oman 1930, p. 295) cites Memoirs of Sir George Bell', i. p 133

- Esdaile 2003, p. 481.

- Robinson 1911, pp. 96–97.

- Robinson 1911, p. 97.

- Simmons & Verner 2012, p. 340.

References

- Esdaile, Charles (2003) [2002]. The Peninsular War. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-6231-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oman, Sir Charles William Chadwick (1930). A History of the Peninsular War: August 1813 – April 14, 1814. VII. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Napier, Sir William Francis Patrick (1879). English battles and sieges in the Peninsula. London: J. Murray. pp. 321–325.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simmons, George; Verner, William Willoughby Cole (2012). A British Rifle Man: The Journals and Correspondence of Major George Simmons, Rifle Brigade, During the Peninsular War and the Campaign of Waterloo. Cambridge University Press. p. 340. ISBN 978-1-108-05409-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Attribution: