Ecology

Ecology (from Greek: οἶκος, "house", or "environment"; -λογία, "study of")[A] is a branch of biology[1] concerning interactions among organisms and their biophysical environment, which includes both biotic and abiotic components. Topics of interest include the biodiversity, distribution, biomass, and populations of organisms, as well as cooperation and competition within and between species. Ecosystems are dynamically interacting systems of organisms, the communities they make up, and the non-living components of their environment. Ecosystem processes, such as primary production, pedogenesis, nutrient cycling, and niche construction, regulate the flux of energy and matter through an environment. These processes are sustained by organisms with specific life history traits.

| |

| |

| |

| Ecology addresses the full scale of life, from tiny bacteria to processes that span the entire planet. Ecologists study many diverse and complex relations among species, such as predation and pollination. The diversity of life is organized into different habitats, from terrestrial (middle) to aquatic ecosystems. |

Ecology is not synonymous with environmentalism, natural history, or environmental science. It overlaps with the closely related sciences of evolutionary biology, genetics, and ethology. An important focus for ecologists is to improve the understanding of how biodiversity affects ecological function. Ecologists seek to explain:

- Life processes, interactions, and adaptations

- The movement of materials and energy through living communities

- The successional development of ecosystems

- The abundance and distribution of organisms and biodiversity in the context of the environment.

Ecology has practical applications in conservation biology, wetland management, natural resource management (agroecology, agriculture, forestry, agroforestry, fisheries), city planning (urban ecology), community health, economics, basic and applied science, and human social interaction (human ecology). It is not treated as separate from humans. Organisms (including humans) and resources compose ecosystems which, in turn, maintain biophysical feedback mechanisms that moderate processes acting on living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) components of the planet. Ecosystems sustain life-supporting functions and produce natural capital like biomass production (food, fuel, fiber, and medicine), the regulation of climate, global biogeochemical cycles, water filtration, soil formation, erosion control, flood protection, and many other natural features of scientific, historical, economic, or intrinsic value.

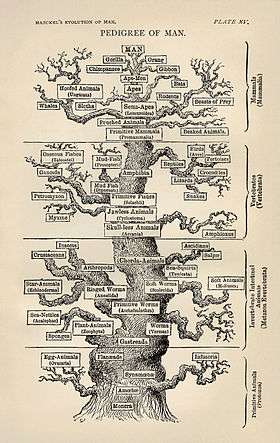

The word "ecology" ("Ökologie") was coined in 1866 by the German scientist Ernst Haeckel. Ecological thought is derivative of established currents in philosophy, particularly from ethics and politics.[2] Ancient Greek philosophers such as Hippocrates and Aristotle laid the foundations of ecology in their studies on natural history. Modern ecology became a much more rigorous science in the late 19th century. Evolutionary concepts relating to adaptation and natural selection became the cornerstones of modern ecological theory.

Levels, scope, and scale of organization

The scope of ecology contains a wide array of interacting levels of organization spanning micro-level (e.g., cells) to a planetary scale (e.g., biosphere) phenomena. Ecosystems, for example, contain abiotic resources and interacting life forms (i.e., individual organisms that aggregate into populations which aggregate into distinct ecological communities). Ecosystems are dynamic, they do not always follow a linear successional path, but they are always changing, sometimes rapidly and sometimes so slowly that it can take thousands of years for ecological processes to bring about certain successional stages of a forest. An ecosystem's area can vary greatly, from tiny to vast. A single tree is of little consequence to the classification of a forest ecosystem, but critically relevant to organisms living in and on it.[3] Several generations of an aphid population can exist over the lifespan of a single leaf. Each of those aphids, in turn, support diverse bacterial communities.[4] The nature of connections in ecological communities cannot be explained by knowing the details of each species in isolation, because the emergent pattern is neither revealed nor predicted until the ecosystem is studied as an integrated whole.[5] Some ecological principles, however, do exhibit collective properties where the sum of the components explain the properties of the whole, such as birth rates of a population being equal to the sum of individual births over a designated time frame.[6]

The main subdisciplines of ecology, population (or community) ecology and ecosystem ecology, exhibit a difference not only of scale, but also of two contrasting paradigms in the field. The former focus on organisms' distribution and abundance, while the later focus on materials and energy fluxes.[7]

Hierarchy

O'Neill et al. (1986)[8]:76

The scale of ecological dynamics can operate like a closed system, such as aphids migrating on a single tree, while at the same time remain open with regard to broader scale influences, such as atmosphere or climate. Hence, ecologists classify ecosystems hierarchically by analyzing data collected from finer scale units, such as vegetation associations, climate, and soil types, and integrate this information to identify emergent patterns of uniform organization and processes that operate on local to regional, landscape, and chronological scales.

To structure the study of ecology into a conceptually manageable framework, the biological world is organized into a nested hierarchy, ranging in scale from genes, to cells, to tissues, to organs, to organisms, to species, to populations, to communities, to ecosystems, to biomes, and up to the level of the biosphere.[9] This framework forms a panarchy[10] and exhibits non-linear behaviors; this means that "effect and cause are disproportionate, so that small changes to critical variables, such as the number of nitrogen fixers, can lead to disproportionate, perhaps irreversible, changes in the system properties."[11]:14

Biodiversity

Noss & Carpenter (1994)[12]:5

Biodiversity (an abbreviation of "biological diversity") describes the diversity of life from genes to ecosystems and spans every level of biological organization. The term has several interpretations, and there are many ways to index, measure, characterize, and represent its complex organization.[13][14][15] Biodiversity includes species diversity, ecosystem diversity, and genetic diversity and scientists are interested in the way that this diversity affects the complex ecological processes operating at and among these respective levels.[14][16][17] Biodiversity plays an important role in ecosystem services which by definition maintain and improve human quality of life.[15][18][19] Conservation priorities and management techniques require different approaches and considerations to address the full ecological scope of biodiversity. Natural capital that supports populations is critical for maintaining ecosystem services[20][21] and species migration (e.g., riverine fish runs and avian insect control) has been implicated as one mechanism by which those service losses are experienced.[22] An understanding of biodiversity has practical applications for species and ecosystem-level conservation planners as they make management recommendations to consulting firms, governments, and industry.[23]

Habitat

.jpg)

The habitat of a species describes the environment over which a species is known to occur and the type of community that is formed as a result.[25] More specifically, "habitats can be defined as regions in environmental space that are composed of multiple dimensions, each representing a biotic or abiotic environmental variable; that is, any component or characteristic of the environment related directly (e.g. forage biomass and quality) or indirectly (e.g. elevation) to the use of a location by the animal."[26]:745 For example, a habitat might be an aquatic or terrestrial environment that can be further categorized as a montane or alpine ecosystem. Habitat shifts provide important evidence of competition in nature where one population changes relative to the habitats that most other individuals of the species occupy. For example, one population of a species of tropical lizard (Tropidurus hispidus) has a flattened body relative to the main populations that live in open savanna. The population that lives in an isolated rock outcrop hides in crevasses where its flattened body offers a selective advantage. Habitat shifts also occur in the developmental life history of amphibians, and in insects that transition from aquatic to terrestrial habitats. Biotope and habitat are sometimes used interchangeably, but the former applies to a community's environment, whereas the latter applies to a species' environment.[25][27][28]

Niche

Definitions of the niche date back to 1917,[31] but G. Evelyn Hutchinson made conceptual advances in 1957[32][33] by introducing a widely adopted definition: "the set of biotic and abiotic conditions in which a species is able to persist and maintain stable population sizes."[31]:519 The ecological niche is a central concept in the ecology of organisms and is sub-divided into the fundamental and the realized niche. The fundamental niche is the set of environmental conditions under which a species is able to persist. The realized niche is the set of environmental plus ecological conditions under which a species persists.[31][33][34] The Hutchinsonian niche is defined more technically as a "Euclidean hyperspace whose dimensions are defined as environmental variables and whose size is a function of the number of values that the environmental values may assume for which an organism has positive fitness."[35]:71

Biogeographical patterns and range distributions are explained or predicted through knowledge of a species' traits and niche requirements.[36] Species have functional traits that are uniquely adapted to the ecological niche. A trait is a measurable property, phenotype, or characteristic of an organism that may influence its survival. Genes play an important role in the interplay of development and environmental expression of traits.[37] Resident species evolve traits that are fitted to the selection pressures of their local environment. This tends to afford them a competitive advantage and discourages similarly adapted species from having an overlapping geographic range. The competitive exclusion principle states that two species cannot coexist indefinitely by living off the same limiting resource; one will always out-compete the other. When similarly adapted species overlap geographically, closer inspection reveals subtle ecological differences in their habitat or dietary requirements.[38] Some models and empirical studies, however, suggest that disturbances can stabilize the co-evolution and shared niche occupancy of similar species inhabiting species-rich communities.[39] The habitat plus the niche is called the ecotope, which is defined as the full range of environmental and biological variables affecting an entire species.[25]

Niche construction

Organisms are subject to environmental pressures, but they also modify their habitats. The regulatory feedback between organisms and their environment can affect conditions from local (e.g., a beaver pond) to global scales, over time and even after death, such as decaying logs or silica skeleton deposits from marine organisms.[40] The process and concept of ecosystem engineering is related to niche construction, but the former relates only to the physical modifications of the habitat whereas the latter also considers the evolutionary implications of physical changes to the environment and the feedback this causes on the process of natural selection. Ecosystem engineers are defined as: "organisms that directly or indirectly modulate the availability of resources to other species, by causing physical state changes in biotic or abiotic materials. In so doing they modify, maintain and create habitats."[41]:373

The ecosystem engineering concept has stimulated a new appreciation for the influence that organisms have on the ecosystem and evolutionary process. The term "niche construction" is more often used in reference to the under-appreciated feedback mechanisms of natural selection imparting forces on the abiotic niche.[29][42] An example of natural selection through ecosystem engineering occurs in the nests of social insects, including ants, bees, wasps, and termites. There is an emergent homeostasis or homeorhesis in the structure of the nest that regulates, maintains and defends the physiology of the entire colony. Termite mounds, for example, maintain a constant internal temperature through the design of air-conditioning chimneys. The structure of the nests themselves are subject to the forces of natural selection. Moreover, a nest can survive over successive generations, so that progeny inherit both genetic material and a legacy niche that was constructed before their time.[6][29][30]

Biome

Biomes are larger units of organization that categorize regions of the Earth's ecosystems, mainly according to the structure and composition of vegetation.[43] There are different methods to define the continental boundaries of biomes dominated by different functional types of vegetative communities that are limited in distribution by climate, precipitation, weather and other environmental variables. Biomes include tropical rainforest, temperate broadleaf and mixed forest, temperate deciduous forest, taiga, tundra, hot desert, and polar desert.[44] Other researchers have recently categorized other biomes, such as the human and oceanic microbiomes. To a microbe, the human body is a habitat and a landscape.[45] Microbiomes were discovered largely through advances in molecular genetics, which have revealed a hidden richness of microbial diversity on the planet. The oceanic microbiome plays a significant role in the ecological biogeochemistry of the planet's oceans.[46]

Biosphere

The largest scale of ecological organization is the biosphere: the total sum of ecosystems on the planet. Ecological relationships regulate the flux of energy, nutrients, and climate all the way up to the planetary scale. For example, the dynamic history of the planetary atmosphere's CO2 and O2 composition has been affected by the biogenic flux of gases coming from respiration and photosynthesis, with levels fluctuating over time in relation to the ecology and evolution of plants and animals.[47] Ecological theory has also been used to explain self-emergent regulatory phenomena at the planetary scale: for example, the Gaia hypothesis is an example of holism applied in ecological theory.[48] The Gaia hypothesis states that there is an emergent feedback loop generated by the metabolism of living organisms that maintains the core temperature of the Earth and atmospheric conditions within a narrow self-regulating range of tolerance.[49]

Population ecology

Population ecology studies the dynamics of species populations and how these populations interact with the wider environment.[6] A population consists of individuals of the same species that live, interact, and migrate through the same niche and habitat.[50]

A primary law of population ecology is the Malthusian growth model[51] which states, "a population will grow (or decline) exponentially as long as the environment experienced by all individuals in the population remains constant."[51]:18 Simplified population models usually start with four variables: death, birth, immigration, and emigration.

An example of an introductory population model describes a closed population, such as on an island, where immigration and emigration does not take place. Hypotheses are evaluated with reference to a null hypothesis which states that random processes create the observed data. In these island models, the rate of population change is described by:

where N is the total number of individuals in the population, b and d are the per capita rates of birth and death respectively, and r is the per capita rate of population change.[51][52]

Using these modelling techniques, Malthus' population principle of growth was later transformed into a model known as the logistic equation:

where N is the number of individuals measured as biomass density, a is the maximum per-capita rate of change, and K is the carrying capacity of the population. The formula states that the rate of change in population size (dN/dT) is equal to growth (aN) that is limited by carrying capacity (1 – N/K).

Population ecology builds upon these introductory models to further understand demographic processes in real study populations. Commonly used types of data include life history, fecundity, and survivorship, and these are analysed using mathematical techniques such as matrix algebra. The information is used for managing wildlife stocks and setting harvest quotas.[52][53] In cases where basic models are insufficient, ecologists may adopt different kinds of statistical methods, such as the Akaike information criterion,[54] or use models that can become mathematically complex as "several competing hypotheses are simultaneously confronted with the data."[55]

Metapopulations and migration

The concept of metapopulations was defined in 1969[56] as "a population of populations which go extinct locally and recolonize".[57]:105 Metapopulation ecology is another statistical approach that is often used in conservation research.[58] Metapopulation models simplify the landscape into patches of varying levels of quality,[59] and metapopulations are linked by the migratory behaviours of organisms. Animal migration is set apart from other kinds of movement; because, it involves the seasonal departure and return of individuals from a habitat.[60] Migration is also a population-level phenomenon, as with the migration routes followed by plants as they occupied northern post-glacial environments. Plant ecologists use pollen records that accumulate and stratify in wetlands to reconstruct the timing of plant migration and dispersal relative to historic and contemporary climates. These migration routes involved an expansion of the range as plant populations expanded from one area to another. There is a larger taxonomy of movement, such as commuting, foraging, territorial behaviour, stasis, and ranging. Dispersal is usually distinguished from migration; because, it involves the one way permanent movement of individuals from their birth population into another population.[61][62]

In metapopulation terminology, migrating individuals are classed as emigrants (when they leave a region) or immigrants (when they enter a region), and sites are classed either as sources or sinks. A site is a generic term that refers to places where ecologists sample populations, such as ponds or defined sampling areas in a forest. Source patches are productive sites that generate a seasonal supply of juveniles that migrate to other patch locations. Sink patches are unproductive sites that only receive migrants; the population at the site will disappear unless rescued by an adjacent source patch or environmental conditions become more favourable. Metapopulation models examine patch dynamics over time to answer potential questions about spatial and demographic ecology. The ecology of metapopulations is a dynamic process of extinction and colonization. Small patches of lower quality (i.e., sinks) are maintained or rescued by a seasonal influx of new immigrants. A dynamic metapopulation structure evolves from year to year, where some patches are sinks in dry years and are sources when conditions are more favourable. Ecologists use a mixture of computer models and field studies to explain metapopulation structure.[63][64]

Community ecology

Johnson & Stinchcomb (2007)[65]:250

Community ecology is the study of the interactions among a collections of species that inhabit the same geographic area. Community ecologists study the determinants of patterns and processes for two or more interacting species. Research in community ecology might measure species diversity in grasslands in relation to soil fertility. It might also include the analysis of predator-prey dynamics, competition among similar plant species, or mutualistic interactions between crabs and corals.

Ecosystem ecology

Tansley (1935)[66]:299

Ecosystems may be habitats within biomes that form an integrated whole and a dynamically responsive system having both physical and biological complexes. Ecosystem ecology is the science of determining the fluxes of materials (e.g. carbon, phosphorus) between different pools (e.g., tree biomass, soil organic material). Ecosystem ecologist attempt to determine the underlying causes of these fluxes. Research in ecosystem ecology might measure primary production (g C/m^2) in a wetland in relation to decomposition and consumption rates (g C/m^2/y). This requires an understanding of the community connections between plants (i.e., primary producers) and the decomposers (e.g., fungi and bacteria),[67]

The underlying concept of ecosystem can be traced back to 1864 in the published work of George Perkins Marsh ("Man and Nature").[68][69] Within an ecosystem, organisms are linked to the physical and biological components of their environment to which they are adapted.[66] Ecosystems are complex adaptive systems where the interaction of life processes form self-organizing patterns across different scales of time and space.[70] Ecosystems are broadly categorized as terrestrial, freshwater, atmospheric, or marine. Differences stem from the nature of the unique physical environments that shapes the biodiversity within each. A more recent addition to ecosystem ecology are technoecosystems, which are affected by or primarily the result of human activity.[6]

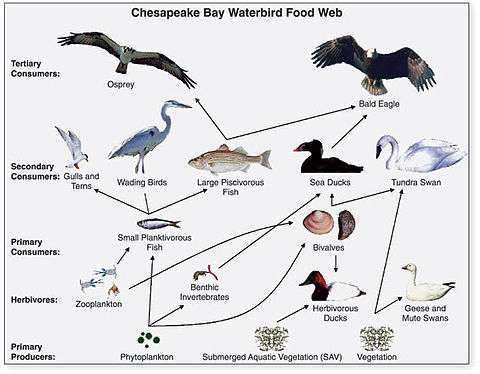

Food webs

A food web is the archetypal ecological network. Plants capture solar energy and use it to synthesize simple sugars during photosynthesis. As plants grow, they accumulate nutrients and are eaten by grazing herbivores, and the energy is transferred through a chain of organisms by consumption. The simplified linear feeding pathways that move from a basal trophic species to a top consumer is called the food chain. The larger interlocking pattern of food chains in an ecological community creates a complex food web. Food webs are a type of concept map or a heuristic device that is used to illustrate and study pathways of energy and material flows.[8][71][72]

Food webs are often limited relative to the real world. Complete empirical measurements are generally restricted to a specific habitat, such as a cave or a pond, and principles gleaned from food web microcosm studies are extrapolated to larger systems.[73] Feeding relations require extensive investigations into the gut contents of organisms, which can be difficult to decipher, or stable isotopes can be used to trace the flow of nutrient diets and energy through a food web.[74] Despite these limitations, food webs remain a valuable tool in understanding community ecosystems.[75]

Food webs exhibit principles of ecological emergence through the nature of trophic relationships: some species have many weak feeding links (e.g., omnivores) while some are more specialized with fewer stronger feeding links (e.g., primary predators). Theoretical and empirical studies identify non-random emergent patterns of few strong and many weak linkages that explain how ecological communities remain stable over time.[76] Food webs are composed of subgroups where members in a community are linked by strong interactions, and the weak interactions occur between these subgroups. This increases food web stability.[77] Step by step lines or relations are drawn until a web of life is illustrated.[72][78][79][80]

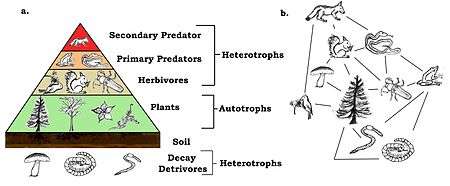

Trophic levels

A trophic level (from Greek troph, τροφή, trophē, meaning "food" or "feeding") is "a group of organisms acquiring a considerable majority of its energy from the lower adjacent level (according to ecological pyramids) nearer the abiotic source."[81]:383 Links in food webs primarily connect feeding relations or trophism among species. Biodiversity within ecosystems can be organized into trophic pyramids, in which the vertical dimension represents feeding relations that become further removed from the base of the food chain up toward top predators, and the horizontal dimension represents the abundance or biomass at each level.[82] When the relative abundance or biomass of each species is sorted into its respective trophic level, they naturally sort into a 'pyramid of numbers'.[83]

Species are broadly categorized as autotrophs (or primary producers), heterotrophs (or consumers), and Detritivores (or decomposers). Autotrophs are organisms that produce their own food (production is greater than respiration) by photosynthesis or chemosynthesis. Heterotrophs are organisms that must feed on others for nourishment and energy (respiration exceeds production).[6] Heterotrophs can be further sub-divided into different functional groups, including primary consumers (strict herbivores), secondary consumers (carnivorous predators that feed exclusively on herbivores), and tertiary consumers (predators that feed on a mix of herbivores and predators).[84] Omnivores do not fit neatly into a functional category because they eat both plant and animal tissues. It has been suggested that omnivores have a greater functional influence as predators, because compared to herbivores, they are relatively inefficient at grazing.[85]

Trophic levels are part of the holistic or complex systems view of ecosystems.[86][87] Each trophic level contains unrelated species that are grouped together because they share common ecological functions, giving a macroscopic view of the system.[88] While the notion of trophic levels provides insight into energy flow and top-down control within food webs, it is troubled by the prevalence of omnivory in real ecosystems. This has led some ecologists to "reiterate that the notion that species clearly aggregate into discrete, homogeneous trophic levels is fiction."[89]:815 Nonetheless, recent studies have shown that real trophic levels do exist, but "above the herbivore trophic level, food webs are better characterized as a tangled web of omnivores."[90]:612

Keystone species

A keystone species is a species that is connected to a disproportionately large number of other species in the food-web. Keystone species have lower levels of biomass in the trophic pyramid relative to the importance of their role. The many connections that a keystone species holds means that it maintains the organization and structure of entire communities. The loss of a keystone species results in a range of dramatic cascading effects that alters trophic dynamics, other food web connections, and can cause the extinction of other species.[91][92]

Sea otters (Enhydra lutris) are commonly cited as an example of a keystone species; because, they limit the density of sea urchins that feed on kelp. If sea otters are removed from the system, the urchins graze until the kelp beds disappear, and this has a dramatic effect on community structure.[93] Hunting of sea otters, for example, is thought to have led indirectly to the extinction of the Steller's sea cow (Hydrodamalis gigas).[94] While the keystone species concept has been used extensively as a conservation tool, it has been criticized for being poorly defined from an operational stance. It is difficult to experimentally determine what species may hold a keystone role in each ecosystem. Furthermore, food web theory suggests that keystone species may not be common, so it is unclear how generally the keystone species model can be applied.[93][95]

Complexity

Complexity is understood as a large computational effort needed to piece together numerous interacting parts exceeding the iterative memory capacity of the human mind. Global patterns of biological diversity are complex. This biocomplexity stems from the interplay among ecological processes that operate and influence patterns at different scales that grade into each other, such as transitional areas or ecotones spanning landscapes. Complexity stems from the interplay among levels of biological organization as energy, and matter is integrated into larger units that superimpose onto the smaller parts. "What were wholes on one level become parts on a higher one."[96]:209 Small scale patterns do not necessarily explain large scale phenomena, otherwise captured in the expression (coined by Aristotle) 'the sum is greater than the parts'.[97][98][E]

"Complexity in ecology is of at least six distinct types: spatial, temporal, structural, process, behavioral, and geometric."[99]:3 From these principles, ecologists have identified emergent and self-organizing phenomena that operate at different environmental scales of influence, ranging from molecular to planetary, and these require different explanations at each integrative level.[49][100] Ecological complexity relates to the dynamic resilience of ecosystems that transition to multiple shifting steady-states directed by random fluctuations of history.[10][101] Long-term ecological studies provide important track records to better understand the complexity and resilience of ecosystems over longer temporal and broader spatial scales. These studies are managed by the International Long Term Ecological Network (LTER).[102] The longest experiment in existence is the Park Grass Experiment, which was initiated in 1856.[103] Another example is the Hubbard Brook study, which has been in operation since 1960.[104]

Holism

Holism remains a critical part of the theoretical foundation in contemporary ecological studies. Holism addresses the biological organization of life that self-organizes into layers of emergent whole systems that function according to non-reducible properties. This means that higher order patterns of a whole functional system, such as an ecosystem, cannot be predicted or understood by a simple summation of the parts.[105] "New properties emerge because the components interact, not because the basic nature of the components is changed."[6]:8

Ecological studies are necessarily holistic as opposed to reductionistic.[37][100][106] Holism has three scientific meanings or uses that identify with ecology: 1) the mechanistic complexity of ecosystems, 2) the practical description of patterns in quantitative reductionist terms where correlations may be identified but nothing is understood about the causal relations without reference to the whole system, which leads to 3) a metaphysical hierarchy whereby the causal relations of larger systems are understood without reference to the smaller parts. Scientific holism differs from mysticism that has appropriated the same term. An example of metaphysical holism is identified in the trend of increased exterior thickness in shells of different species. The reason for a thickness increase can be understood through reference to principles of natural selection via predation without need to reference or understand the biomolecular properties of the exterior shells.[107]

Relation to evolution

Ecology and evolutionary biology are considered sister disciplines of the life sciences. Natural selection, life history, development, adaptation, populations, and inheritance are examples of concepts that thread equally into ecological and evolutionary theory. Morphological, behavioural, and genetic traits, for example, can be mapped onto evolutionary trees to study the historical development of a species in relation to their functions and roles in different ecological circumstances. In this framework, the analytical tools of ecologists and evolutionists overlap as they organize, classify, and investigate life through common systematic principles, such as phylogenetics or the Linnaean system of taxonomy.[108] The two disciplines often appear together, such as in the title of the journal Trends in Ecology and Evolution.[109] There is no sharp boundary separating ecology from evolution, and they differ more in their areas of applied focus. Both disciplines discover and explain emergent and unique properties and processes operating across different spatial or temporal scales of organization.[37][49] While the boundary between ecology and evolution is not always clear, ecologists study the abiotic and biotic factors that influence evolutionary processes,[110][111] and evolution can be rapid, occurring on ecological timescales as short as one generation.[112]

Behavioural ecology

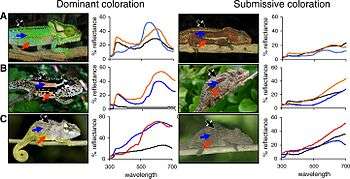

All organisms can exhibit behaviours. Even plants express complex behaviour, including memory and communication.[114] Behavioural ecology is the study of an organism's behaviour in its environment and its ecological and evolutionary implications. Ethology is the study of observable movement or behaviour in animals. This could include investigations of motile sperm of plants, mobile phytoplankton, zooplankton swimming toward the female egg, the cultivation of fungi by weevils, the mating dance of a salamander, or social gatherings of amoeba.[115][116][117][118][119]

Adaptation is the central unifying concept in behavioural ecology.[120] Behaviours can be recorded as traits and inherited in much the same way that eye and hair colour can. Behaviours can evolve by means of natural selection as adaptive traits conferring functional utilities that increases reproductive fitness.[121][122]

Predator-prey interactions are an introductory concept into food-web studies as well as behavioural ecology.[124] Prey species can exhibit different kinds of behavioural adaptations to predators, such as avoid, flee, or defend. Many prey species are faced with multiple predators that differ in the degree of danger posed. To be adapted to their environment and face predatory threats, organisms must balance their energy budgets as they invest in different aspects of their life history, such as growth, feeding, mating, socializing, or modifying their habitat. Hypotheses posited in behavioural ecology are generally based on adaptive principles of conservation, optimization, or efficiency.[34][110][125] For example, "[t]he threat-sensitive predator avoidance hypothesis predicts that prey should assess the degree of threat posed by different predators and match their behaviour according to current levels of risk"[126] or "[t]he optimal flight initiation distance occurs where expected postencounter fitness is maximized, which depends on the prey's initial fitness, benefits obtainable by not fleeing, energetic escape costs, and expected fitness loss due to predation risk."[127]

Elaborate sexual displays and posturing are encountered in the behavioural ecology of animals. The birds-of-paradise, for example, sing and display elaborate ornaments during courtship. These displays serve a dual purpose of signalling healthy or well-adapted individuals and desirable genes. The displays are driven by sexual selection as an advertisement of quality of traits among suitors.[128]

Cognitive ecology

Cognitive ecology integrates theory and observations from evolutionary ecology and neurobiology, primarily cognitive science, in order to understand the effect that animal interaction with their habitat has on their cognitive systems and how those systems restrict behavior within an ecological and evolutionary framework.[129] "Until recently, however, cognitive scientists have not paid sufficient attention to the fundamental fact that cognitive traits evolved under particular natural settings. With consideration of the selection pressure on cognition, cognitive ecology can contribute intellectual coherence to the multidisciplinary study of cognition."[130][131] As a study involving the 'coupling' or interactions between organism and environment, cognitive ecology is closely related to enactivism,[129] a field based upon the view that "...we must see the organism and environment as bound together in reciprocal specification and selection...".[132]

Social ecology

Social ecological behaviours are notable in the social insects, slime moulds, social spiders, human society, and naked mole-rats where eusocialism has evolved. Social behaviours include reciprocally beneficial behaviours among kin and nest mates[117][122][133] and evolve from kin and group selection. Kin selection explains altruism through genetic relationships, whereby an altruistic behaviour leading to death is rewarded by the survival of genetic copies distributed among surviving relatives. The social insects, including ants, bees, and wasps are most famously studied for this type of relationship because the male drones are clones that share the same genetic make-up as every other male in the colony.[122] In contrast, group selectionists find examples of altruism among non-genetic relatives and explain this through selection acting on the group; whereby, it becomes selectively advantageous for groups if their members express altruistic behaviours to one another. Groups with predominantly altruistic members survive better than groups with predominantly selfish members.[122][134]

Coevolution

Ecological interactions can be classified broadly into a host and an associate relationship. A host is any entity that harbours another that is called the associate.[135] Relationships within a species that are mutually or reciprocally beneficial are called mutualisms. Examples of mutualism include fungus-growing ants employing agricultural symbiosis, bacteria living in the guts of insects and other organisms, the fig wasp and yucca moth pollination complex, lichens with fungi and photosynthetic algae, and corals with photosynthetic algae.[136][137] If there is a physical connection between host and associate, the relationship is called symbiosis. Approximately 60% of all plants, for example, have a symbiotic relationship with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi living in their roots forming an exchange network of carbohydrates for mineral nutrients.[138]

Indirect mutualisms occur where the organisms live apart. For example, trees living in the equatorial regions of the planet supply oxygen into the atmosphere that sustains species living in distant polar regions of the planet. This relationship is called commensalism; because, many others receive the benefits of clean air at no cost or harm to trees supplying the oxygen.[6][139] If the associate benefits while the host suffers, the relationship is called parasitism. Although parasites impose a cost to their host (e.g., via damage to their reproductive organs or propagules, denying the services of a beneficial partner), their net effect on host fitness is not necessarily negative and, thus, becomes difficult to forecast.[140][141] Co-evolution is also driven by competition among species or among members of the same species under the banner of reciprocal antagonism, such as grasses competing for growth space. The Red Queen Hypothesis, for example, posits that parasites track down and specialize on the locally common genetic defense systems of its host that drives the evolution of sexual reproduction to diversify the genetic constituency of populations responding to the antagonistic pressure.[142][143]

Biogeography

Biogeography (an amalgamation of biology and geography) is the comparative study of the geographic distribution of organisms and the corresponding evolution of their traits in space and time.[144] The Journal of Biogeography was established in 1974.[145] Biogeography and ecology share many of their disciplinary roots. For example, the theory of island biogeography, published by the Robert MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson in 1967[146] is considered one of the fundamentals of ecological theory.[147]

Biogeography has a long history in the natural sciences concerning the spatial distribution of plants and animals. Ecology and evolution provide the explanatory context for biogeographical studies.[144] Biogeographical patterns result from ecological processes that influence range distributions, such as migration and dispersal.[147] and from historical processes that split populations or species into different areas. The biogeographic processes that result in the natural splitting of species explains much of the modern distribution of the Earth's biota. The splitting of lineages in a species is called vicariance biogeography and it is a sub-discipline of biogeography.[148] There are also practical applications in the field of biogeography concerning ecological systems and processes. For example, the range and distribution of biodiversity and invasive species responding to climate change is a serious concern and active area of research in the context of global warming.[149][150]

r/K selection theory

A population ecology concept is r/K selection theory,[D] one of the first predictive models in ecology used to explain life-history evolution. The premise behind the r/K selection model is that natural selection pressures change according to population density. For example, when an island is first colonized, density of individuals is low. The initial increase in population size is not limited by competition, leaving an abundance of available resources for rapid population growth. These early phases of population growth experience density-independent forces of natural selection, which is called r-selection. As the population becomes more crowded, it approaches the island's carrying capacity, thus forcing individuals to compete more heavily for fewer available resources. Under crowded conditions, the population experiences density-dependent forces of natural selection, called K-selection.[151]

In the r/K-selection model, the first variable r is the intrinsic rate of natural increase in population size and the second variable K is the carrying capacity of a population.[34] Different species evolve different life-history strategies spanning a continuum between these two selective forces. An r-selected species is one that has high birth rates, low levels of parental investment, and high rates of mortality before individuals reach maturity. Evolution favours high rates of fecundity in r-selected species. Many kinds of insects and invasive species exhibit r-selected characteristics. In contrast, a K-selected species has low rates of fecundity, high levels of parental investment in the young, and low rates of mortality as individuals mature. Humans and elephants are examples of species exhibiting K-selected characteristics, including longevity and efficiency in the conversion of more resources into fewer offspring.[146][152]

Molecular ecology

The important relationship between ecology and genetic inheritance predates modern techniques for molecular analysis. Molecular ecological research became more feasible with the development of rapid and accessible genetic technologies, such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The rise of molecular technologies and influx of research questions into this new ecological field resulted in the publication Molecular Ecology in 1992.[153] Molecular ecology uses various analytical techniques to study genes in an evolutionary and ecological context. In 1994, John Avise also played a leading role in this area of science with the publication of his book, Molecular Markers, Natural History and Evolution.[154] Newer technologies opened a wave of genetic analysis into organisms once difficult to study from an ecological or evolutionary standpoint, such as bacteria, fungi, and nematodes. Molecular ecology engendered a new research paradigm for investigating ecological questions considered otherwise intractable. Molecular investigations revealed previously obscured details in the tiny intricacies of nature and improved resolution into probing questions about behavioural and biogeographical ecology.[154] For example, molecular ecology revealed promiscuous sexual behaviour and multiple male partners in tree swallows previously thought to be socially monogamous.[155] In a biogeographical context, the marriage between genetics, ecology, and evolution resulted in a new sub-discipline called phylogeography.[156]

Human ecology

Rachel Carson, "Silent Spring"[157]

Ecology is as much a biological science as it is a human science.[6] Human ecology is an interdisciplinary investigation into the ecology of our species. "Human ecology may be defined: (1) from a bioecological standpoint as the study of man as the ecological dominant in plant and animal communities and systems; (2) from a bioecological standpoint as simply another animal affecting and being affected by his physical environment; and (3) as a human being, somehow different from animal life in general, interacting with physical and modified environments in a distinctive and creative way. A truly interdisciplinary human ecology will most likely address itself to all three."[158]:3 The term was formally introduced in 1921, but many sociologists, geographers, psychologists, and other disciplines were interested in human relations to natural systems centuries prior, especially in the late 19th century.[158][159]

The ecological complexities human beings are facing through the technological transformation of the planetary biome has brought on the Anthropocene. The unique set of circumstances has generated the need for a new unifying science called coupled human and natural systems that builds upon, but moves beyond the field of human ecology.[105] Ecosystems tie into human societies through the critical and all encompassing life-supporting functions they sustain. In recognition of these functions and the incapability of traditional economic valuation methods to see the value in ecosystems, there has been a surge of interest in social-natural capital, which provides the means to put a value on the stock and use of information and materials stemming from ecosystem goods and services. Ecosystems produce, regulate, maintain, and supply services of critical necessity and beneficial to human health (cognitive and physiological), economies, and they even provide an information or reference function as a living library giving opportunities for science and cognitive development in children engaged in the complexity of the natural world. Ecosystems relate importantly to human ecology as they are the ultimate base foundation of global economics as every commodity, and the capacity for exchange ultimately stems from the ecosystems on Earth.[105][160][161][162]

Restoration and management

Grumbine (1994)[163]:27

Ecology is an employed science of restoration, repairing disturbed sites through human intervention, in natural resource management, and in environmental impact assessments. Edward O. Wilson predicted in 1992 that the 21st century "will be the era of restoration in ecology".[164] Ecological science has boomed in the industrial investment of restoring ecosystems and their processes in abandoned sites after disturbance. Natural resource managers, in forestry, for example, employ ecologists to develop, adapt, and implement ecosystem based methods into the planning, operation, and restoration phases of land-use. Ecological science is used in the methods of sustainable harvesting, disease, and fire outbreak management, in fisheries stock management, for integrating land-use with protected areas and communities, and conservation in complex geo-political landscapes.[23][163][165][166]

Relation to the environment

The environment of ecosystems includes both physical parameters and biotic attributes. It is dynamically interlinked, and contains resources for organisms at any time throughout their life cycle.[6][167] Like ecology, the term environment has different conceptual meanings and overlaps with the concept of nature. Environment "includes the physical world, the social world of human relations and the built world of human creation."[168]:62 The physical environment is external to the level of biological organization under investigation, including abiotic factors such as temperature, radiation, light, chemistry, climate and geology. The biotic environment includes genes, cells, organisms, members of the same species (conspecifics) and other species that share a habitat.[169]

The distinction between external and internal environments, however, is an abstraction parsing life and environment into units or facts that are inseparable in reality. There is an interpenetration of cause and effect between the environment and life. The laws of thermodynamics, for example, apply to ecology by means of its physical state. With an understanding of metabolic and thermodynamic principles, a complete accounting of energy and material flow can be traced through an ecosystem. In this way, the environmental and ecological relations are studied through reference to conceptually manageable and isolated material parts. After the effective environmental components are understood through reference to their causes; however, they conceptually link back together as an integrated whole, or holocoenotic system as it was once called. This is known as the dialectical approach to ecology. The dialectical approach examines the parts, but integrates the organism and the environment into a dynamic whole (or umwelt). Change in one ecological or environmental factor can concurrently affect the dynamic state of an entire ecosystem.[37][170]

Disturbance and resilience

Ecosystems are regularly confronted with natural environmental variations and disturbances over time and geographic space. A disturbance is any process that removes biomass from a community, such as a fire, flood, drought, or predation.[171] Disturbances occur over vastly different ranges in terms of magnitudes as well as distances and time periods,[172] and are both the cause and product of natural fluctuations in death rates, species assemblages, and biomass densities within an ecological community. These disturbances create places of renewal where new directions emerge from the patchwork of natural experimentation and opportunity.[171][173][174] Ecological resilience is a cornerstone theory in ecosystem management. Biodiversity fuels the resilience of ecosystems acting as a kind of regenerative insurance.[174]

Metabolism and the early atmosphere

Ernest et al.[175]:991

The Earth was formed approximately 4.5 billion years ago.[176] As it cooled and a crust and oceans formed, its atmosphere transformed from being dominated by hydrogen to one composed mostly of methane and ammonia. Over the next billion years, the metabolic activity of life transformed the atmosphere into a mixture of carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and water vapor. These gases changed the way that light from the sun hit the Earth's surface and greenhouse effects trapped heat. There were untapped sources of free energy within the mixture of reducing and oxidizing gasses that set the stage for primitive ecosystems to evolve and, in turn, the atmosphere also evolved.[177]

Throughout history, the Earth's atmosphere and biogeochemical cycles have been in a dynamic equilibrium with planetary ecosystems. The history is characterized by periods of significant transformation followed by millions of years of stability.[178] The evolution of the earliest organisms, likely anaerobic methanogen microbes, started the process by converting atmospheric hydrogen into methane (4H2 + CO2 → CH4 + 2H2O). Anoxygenic photosynthesis reduced hydrogen concentrations and increased atmospheric methane, by converting hydrogen sulfide into water or other sulfur compounds (for example, 2H2S + CO2 + hv → CH2O + H2O + 2S). Early forms of fermentation also increased levels of atmospheric methane. The transition to an oxygen-dominant atmosphere (the Great Oxidation) did not begin until approximately 2.4–2.3 billion years ago, but photosynthetic processes started 0.3 to 1 billion years prior.[178][179]

Radiation: heat, temperature and light

The biology of life operates within a certain range of temperatures. Heat is a form of energy that regulates temperature. Heat affects growth rates, activity, behaviour, and primary production. Temperature is largely dependent on the incidence of solar radiation. The latitudinal and longitudinal spatial variation of temperature greatly affects climates and consequently the distribution of biodiversity and levels of primary production in different ecosystems or biomes across the planet. Heat and temperature relate importantly to metabolic activity. Poikilotherms, for example, have a body temperature that is largely regulated and dependent on the temperature of the external environment. In contrast, homeotherms regulate their internal body temperature by expending metabolic energy.[110][111][170]

There is a relationship between light, primary production, and ecological energy budgets. Sunlight is the primary input of energy into the planet's ecosystems. Light is composed of electromagnetic energy of different wavelengths. Radiant energy from the sun generates heat, provides photons of light measured as active energy in the chemical reactions of life, and also acts as a catalyst for genetic mutation.[110][111][170] Plants, algae, and some bacteria absorb light and assimilate the energy through photosynthesis. Organisms capable of assimilating energy by photosynthesis or through inorganic fixation of H2S are autotrophs. Autotrophs—responsible for primary production—assimilate light energy which becomes metabolically stored as potential energy in the form of biochemical enthalpic bonds.[110][111][170]

Physical environments

Water

Cronk & Fennessy (2001)[180]:29

Diffusion of carbon dioxide and oxygen is approximately 10,000 times slower in water than in air. When soils are flooded, they quickly lose oxygen, becoming hypoxic (an environment with O2 concentration below 2 mg/liter) and eventually completely anoxic where anaerobic bacteria thrive among the roots. Water also influences the intensity and spectral composition of light as it reflects off the water surface and submerged particles.[180] Aquatic plants exhibit a wide variety of morphological and physiological adaptations that allow them to survive, compete, and diversify in these environments. For example, their roots and stems contain large air spaces (aerenchyma) that regulate the efficient transportation of gases (for example, CO2 and O2) used in respiration and photosynthesis. Salt water plants (halophytes) have additional specialized adaptations, such as the development of special organs for shedding salt and osmoregulating their internal salt (NaCl) concentrations, to live in estuarine, brackish, or oceanic environments. Anaerobic soil microorganisms in aquatic environments use nitrate, manganese ions, ferric ions, sulfate, carbon dioxide, and some organic compounds; other microorganisms are facultative anaerobes and use oxygen during respiration when the soil becomes drier. The activity of soil microorganisms and the chemistry of the water reduces the oxidation-reduction potentials of the water. Carbon dioxide, for example, is reduced to methane (CH4) by methanogenic bacteria.[180] The physiology of fish is also specially adapted to compensate for environmental salt levels through osmoregulation. Their gills form electrochemical gradients that mediate salt excretion in salt water and uptake in fresh water.[181]

Gravity

The shape and energy of the land is significantly affected by gravitational forces. On a large scale, the distribution of gravitational forces on the earth is uneven and influences the shape and movement of tectonic plates as well as influencing geomorphic processes such as orogeny and erosion. These forces govern many of the geophysical properties and distributions of ecological biomes across the Earth. On the organismal scale, gravitational forces provide directional cues for plant and fungal growth (gravitropism), orientation cues for animal migrations, and influence the biomechanics and size of animals.[110] Ecological traits, such as allocation of biomass in trees during growth are subject to mechanical failure as gravitational forces influence the position and structure of branches and leaves.[182] The cardiovascular systems of animals are functionally adapted to overcome pressure and gravitational forces that change according to the features of organisms (e.g., height, size, shape), their behaviour (e.g., diving, running, flying), and the habitat occupied (e.g., water, hot deserts, cold tundra).[183]

Pressure

Climatic and osmotic pressure places physiological constraints on organisms, especially those that fly and respire at high altitudes, or dive to deep ocean depths.[184] These constraints influence vertical limits of ecosystems in the biosphere, as organisms are physiologically sensitive and adapted to atmospheric and osmotic water pressure differences.[110] For example, oxygen levels decrease with decreasing pressure and are a limiting factor for life at higher altitudes.[185] Water transportation by plants is another important ecophysiological process affected by osmotic pressure gradients.[186][187][188] Water pressure in the depths of oceans requires that organisms adapt to these conditions. For example, diving animals such as whales, dolphins, and seals are specially adapted to deal with changes in sound due to water pressure differences.[189] Differences between hagfish species provide another example of adaptation to deep-sea pressure through specialized protein adaptations.[190]

Wind and turbulence

Turbulent forces in air and water affect the environment and ecosystem distribution, form and dynamics. On a planetary scale, ecosystems are affected by circulation patterns in the global trade winds. Wind power and the turbulent forces it creates can influence heat, nutrient, and biochemical profiles of ecosystems.[110] For example, wind running over the surface of a lake creates turbulence, mixing the water column and influencing the environmental profile to create thermally layered zones, affecting how fish, algae, and other parts of the aquatic ecosystem are structured.[193][194] Wind speed and turbulence also influence evapotranspiration rates and energy budgets in plants and animals.[180][195] Wind speed, temperature and moisture content can vary as winds travel across different land features and elevations. For example, the westerlies come into contact with the coastal and interior mountains of western North America to produce a rain shadow on the leeward side of the mountain. The air expands and moisture condenses as the winds increase in elevation; this is called orographic lift and can cause precipitation. This environmental process produces spatial divisions in biodiversity, as species adapted to wetter conditions are range-restricted to the coastal mountain valleys and unable to migrate across the xeric ecosystems (e.g., of the Columbia Basin in western North America) to intermix with sister lineages that are segregated to the interior mountain systems.[196][197]

Fire

Plants convert carbon dioxide into biomass and emit oxygen into the atmosphere. By approximately 350 million years ago (the end of the Devonian period), photosynthesis had brought the concentration of atmospheric oxygen above 17%, which allowed combustion to occur.[198] Fire releases CO2 and converts fuel into ash and tar. Fire is a significant ecological parameter that raises many issues pertaining to its control and suppression.[199] While the issue of fire in relation to ecology and plants has been recognized for a long time,[200] Charles Cooper brought attention to the issue of forest fires in relation to the ecology of forest fire suppression and management in the 1960s.[201][202]

Native North Americans were among the first to influence fire regimes by controlling their spread near their homes or by lighting fires to stimulate the production of herbaceous foods and basketry materials.[203] Fire creates a heterogeneous ecosystem age and canopy structure, and the altered soil nutrient supply and cleared canopy structure opens new ecological niches for seedling establishment.[204][205] Most ecosystems are adapted to natural fire cycles. Plants, for example, are equipped with a variety of adaptations to deal with forest fires. Some species (e.g., Pinus halepensis) cannot germinate until after their seeds have lived through a fire or been exposed to certain compounds from smoke. Environmentally triggered germination of seeds is called serotiny.[206][207] Fire plays a major role in the persistence and resilience of ecosystems.[173]

Soils

Soil is the living top layer of mineral and organic dirt that covers the surface of the planet. It is the chief organizing centre of most ecosystem functions, and it is of critical importance in agricultural science and ecology. The decomposition of dead organic matter (for example, leaves on the forest floor), results in soils containing minerals and nutrients that feed into plant production. The whole of the planet's soil ecosystems is called the pedosphere where a large biomass of the Earth's biodiversity organizes into trophic levels. Invertebrates that feed and shred larger leaves, for example, create smaller bits for smaller organisms in the feeding chain. Collectively, these organisms are the detritivores that regulate soil formation.[208][209] Tree roots, fungi, bacteria, worms, ants, beetles, centipedes, spiders, mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and other less familiar creatures all work to create the trophic web of life in soil ecosystems. Soils form composite phenotypes where inorganic matter is enveloped into the physiology of a whole community. As organisms feed and migrate through soils they physically displace materials, an ecological process called bioturbation. This aerates soils and stimulates heterotrophic growth and production. Soil microorganisms are influenced by and feed back into the trophic dynamics of the ecosystem. No single axis of causality can be discerned to segregate the biological from geomorphological systems in soils.[210][211] Paleoecological studies of soils places the origin for bioturbation to a time before the Cambrian period. Other events, such as the evolution of trees and the colonization of land in the Devonian period played a significant role in the early development of ecological trophism in soils.[209][212][213]

Biogeochemistry and climate

Ecologists study and measure nutrient budgets to understand how these materials are regulated, flow, and recycled through the environment.[110][111][170] This research has led to an understanding that there is global feedback between ecosystems and the physical parameters of this planet, including minerals, soil, pH, ions, water, and atmospheric gases. Six major elements (hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sulfur, and phosphorus; H, C, N, O, S, and P) form the constitution of all biological macromolecules and feed into the Earth's geochemical processes. From the smallest scale of biology, the combined effect of billions upon billions of ecological processes amplify and ultimately regulate the biogeochemical cycles of the Earth. Understanding the relations and cycles mediated between these elements and their ecological pathways has significant bearing toward understanding global biogeochemistry.[214]

The ecology of global carbon budgets gives one example of the linkage between biodiversity and biogeochemistry. It is estimated that the Earth's oceans hold 40,000 gigatonnes (Gt) of carbon, that vegetation and soil hold 2070 Gt, and that fossil fuel emissions are 6.3 Gt carbon per year.[215] There have been major restructurings in these global carbon budgets during the Earth's history, regulated to a large extent by the ecology of the land. For example, through the early-mid Eocene volcanic outgassing, the oxidation of methane stored in wetlands, and seafloor gases increased atmospheric CO2 (carbon dioxide) concentrations to levels as high as 3500 ppm.[216]

In the Oligocene, from twenty-five to thirty-two million years ago, there was another significant restructuring of the global carbon cycle as grasses evolved a new mechanism of photosynthesis, C4 photosynthesis, and expanded their ranges. This new pathway evolved in response to the drop in atmospheric CO2 concentrations below 550 ppm.[217] The relative abundance and distribution of biodiversity alters the dynamics between organisms and their environment such that ecosystems can be both cause and effect in relation to climate change. Human-driven modifications to the planet's ecosystems (e.g., disturbance, biodiversity loss, agriculture) contributes to rising atmospheric greenhouse gas levels. Transformation of the global carbon cycle in the next century is projected to raise planetary temperatures, lead to more extreme fluctuations in weather, alter species distributions, and increase extinction rates. The effect of global warming is already being registered in melting glaciers, melting mountain ice caps, and rising sea levels. Consequently, species distributions are changing along waterfronts and in continental areas where migration patterns and breeding grounds are tracking the prevailing shifts in climate. Large sections of permafrost are also melting to create a new mosaic of flooded areas having increased rates of soil decomposition activity that raises methane (CH4) emissions. There is concern over increases in atmospheric methane in the context of the global carbon cycle, because methane is a greenhouse gas that is 23 times more effective at absorbing long-wave radiation than CO2 on a 100-year time scale.[218] Hence, there is a relationship between global warming, decomposition and respiration in soils and wetlands producing significant climate feedbacks and globally altered biogeochemical cycles.[105][219][220][221][222][223]

History

Early beginnings

Ecology has a complex origin, due in large part to its interdisciplinary nature.[225] Ancient Greek philosophers such as Hippocrates and Aristotle were among the first to record observations on natural history. However, they viewed life in terms of essentialism, where species were conceptualized as static unchanging things while varieties were seen as aberrations of an idealized type. This contrasts against the modern understanding of ecological theory where varieties are viewed as the real phenomena of interest and having a role in the origins of adaptations by means of natural selection.[6][226][227] Early conceptions of ecology, such as a balance and regulation in nature can be traced to Herodotus (died c. 425 BC), who described one of the earliest accounts of mutualism in his observation of "natural dentistry". Basking Nile crocodiles, he noted, would open their mouths to give sandpipers safe access to pluck leeches out, giving nutrition to the sandpiper and oral hygiene for the crocodile.[225] Aristotle was an early influence on the philosophical development of ecology. He and his student Theophrastus made extensive observations on plant and animal migrations, biogeography, physiology, and on their behaviour, giving an early analogue to the modern concept of an ecological niche.[228][229]

Stephen Forbes (1887)[230]

Ecological concepts such as food chains, population regulation, and productivity were first developed in the 1700s, through the published works of microscopist Antoni van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) and botanist Richard Bradley (1688?–1732).[6] Biogeographer Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) was an early pioneer in ecological thinking and was among the first to recognize ecological gradients, where species are replaced or altered in form along environmental gradients, such as a cline forming along a rise in elevation. Humboldt drew inspiration from Isaac Newton as he developed a form of "terrestrial physics". In Newtonian fashion, he brought a scientific exactitude for measurement into natural history and even alluded to concepts that are the foundation of a modern ecological law on species-to-area relationships.[231][232][233] Natural historians, such as Humboldt, James Hutton, and Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (among others) laid the foundations of the modern ecological sciences.[234] The term "ecology" (German: Oekologie, Ökologie) was coined by Ernst Haeckel in his book Generelle Morphologie der Organismen (1866).[235] Haeckel was a zoologist, artist, writer, and later in life a professor of comparative anatomy.[224][236]

Opinions differ on who was the founder of modern ecological theory. Some mark Haeckel's definition as the beginning;[237] others say it was Eugenius Warming with the writing of Oecology of Plants: An Introduction to the Study of Plant Communities (1895),[238] or Carl Linnaeus' principles on the economy of nature that matured in the early 18th century.[239][240] Linnaeus founded an early branch of ecology that he called the economy of nature.[239] His works influenced Charles Darwin, who adopted Linnaeus' phrase on the economy or polity of nature in The Origin of Species.[224] Linnaeus was the first to frame the balance of nature as a testable hypothesis. Haeckel, who admired Darwin's work, defined ecology in reference to the economy of nature, which has led some to question whether ecology and the economy of nature are synonymous.[240]

From Aristotle until Darwin, the natural world was predominantly considered static and unchanging. Prior to The Origin of Species, there was little appreciation or understanding of the dynamic and reciprocal relations between organisms, their adaptations, and the environment.[226] An exception is the 1789 publication Natural History of Selborne by Gilbert White (1720–1793), considered by some to be one of the earliest texts on ecology.[243] While Charles Darwin is mainly noted for his treatise on evolution,[244] he was one of the founders of soil ecology,[245] and he made note of the first ecological experiment in The Origin of Species.[241] Evolutionary theory changed the way that researchers approached the ecological sciences.[246]

Since 1900

Modern ecology is a young science that first attracted substantial scientific attention toward the end of the 19th century (around the same time that evolutionary studies were gaining scientific interest). The scientist Ellen Swallow Richards may have first introduced the term "oekology" (which eventually morphed into home economics) in the U.S. as early 1892.[247]

In the early 20th century, ecology transitioned from a more descriptive form of natural history to a more analytical form of scientific natural history.[231][234] Frederic Clements published the first American ecology book in 1905,[248] presenting the idea of plant communities as a superorganism. This publication launched a debate between ecological holism and individualism that lasted until the 1970s. Clements' superorganism concept proposed that ecosystems progress through regular and determined stages of seral development that are analogous to the developmental stages of an organism. The Clementsian paradigm was challenged by Henry Gleason,[249] who stated that ecological communities develop from the unique and coincidental association of individual organisms. This perceptual shift placed the focus back onto the life histories of individual organisms and how this relates to the development of community associations.[250]

The Clementsian superorganism theory was an overextended application of an idealistic form of holism.[37][107] The term "holism" was coined in 1926 by Jan Christiaan Smuts, a South African general and polarizing historical figure who was inspired by Clements' superorganism concept.[251][C] Around the same time, Charles Elton pioneered the concept of food chains in his classical book Animal Ecology.[83] Elton[83] defined ecological relations using concepts of food chains, food cycles, and food size, and described numerical relations among different functional groups and their relative abundance. Elton's 'food cycle' was replaced by 'food web' in a subsequent ecological text.[252] Alfred J. Lotka brought in many theoretical concepts applying thermodynamic principles to ecology.

In 1942, Raymond Lindeman wrote a landmark paper on the trophic dynamics of ecology, which was published posthumously after initially being rejected for its theoretical emphasis. Trophic dynamics became the foundation for much of the work to follow on energy and material flow through ecosystems. Robert MacArthur advanced mathematical theory, predictions, and tests in ecology in the 1950s, which inspired a resurgent school of theoretical mathematical ecologists.[234][253][254] Ecology also has developed through contributions from other nations, including Russia's Vladimir Vernadsky and his founding of the biosphere concept in the 1920s[255] and Japan's Kinji Imanishi and his concepts of harmony in nature and habitat segregation in the 1950s.[256] Scientific recognition of contributions to ecology from non-English-speaking cultures is hampered by language and translation barriers.[255]

Rachel Carson (1962)[257]:48

Ecology surged in popular and scientific interest during the 1960–1970s environmental movement. There are strong historical and scientific ties between ecology, environmental management, and protection.[234] The historical emphasis and poetic naturalistic writings advocating the protection of wild places by notable ecologists in the history of conservation biology, such as Aldo Leopold and Arthur Tansley, have been seen as far removed from urban centres where, it is claimed, the concentration of pollution and environmental degradation is located.[234][258] Palamar (2008)[258] notes an overshadowing by mainstream environmentalism of pioneering women in the early 1900s who fought for urban health ecology (then called euthenics)[247] and brought about changes in environmental legislation. Women such as Ellen Swallow Richards and Julia Lathrop, among others, were precursors to the more popularized environmental movements after the 1950s.

In 1962, marine biologist and ecologist Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring helped to mobilize the environmental movement by alerting the public to toxic pesticides, such as DDT, bioaccumulating in the environment. Carson used ecological science to link the release of environmental toxins to human and ecosystem health. Since then, ecologists have worked to bridge their understanding of the degradation of the planet's ecosystems with environmental politics, law, restoration, and natural resources management.[23][234][258][259]

See also

- Chemical ecology

- Circles of Sustainability

- Cultural ecology

- Dialectical naturalism

- Ecological death

- Ecological psychology

- Ecology movement

- Ecosophy

- Ecopsychology

- Industrial ecology

- Information ecology

- Landscape ecology

- Natural resource

- Normative science

- Political ecology

- Sensory ecology

- Spiritual ecology

- Sustainable development

- Lists

- Glossary of ecology

- Index of biology articles

- List of ecologists

- Outline of biology

- Terminology of ecology

Notes

- ^ In Ernst Haeckel's (1866) footnote where the term ecology originates, he also gives attribute to Ancient Greek: χώρας, romanized: khōrā, lit. 'χωρα', meaning "dwelling place, distributional area" —quoted from Stauffer (1957).

- ^ This is a copy of Haeckel's original definition (Original: Haeckel, E. (1866) Generelle Morphologie der Organismen. Allgemeine Grundzige der organischen Formen- Wissenschaft, mechanisch begriindet durch die von Charles Darwin reformirte Descendenz-Theorie. 2 vols. Reimer, Berlin.) translated and quoted from Stauffer (1957).

- ^ Foster & Clark (2008) note how Smut's holism contrasts starkly against his racial political views as the father of apartheid.

- ^ First introduced in MacArthur & Wilson's (1967) book of notable mention in the history and theoretical science of ecology, The Theory of Island Biogeography.

- ^ Aristotle wrote about this concept in Metaphysics (Quoted from The Internet Classics Archive translation by W. D. Ross. Book VIII, Part 6): "To return to the difficulty which has been stated with respect both to definitions and to numbers, what is the cause of their unity? In the case of all things which have several parts and in which the totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is something beside the parts, there is a cause; for even in bodies contact is the cause of unity in some cases, and in others viscosity or some other such quality."

References

- "the definition of ecology". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- Eric Laferrière; Peter J. Stoett (2 September 2003). International Relations Theory and Ecological Thought: Towards a Synthesis. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-134-71068-3.

- Stadler, B.; Michalzik, B.; Müller, T. (1998). "Linking aphid ecology with nutrient fluxes in a coniferous forest". Ecology. 79 (5): 1514–1525. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[1514:LAEWNF]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0012-9658.

- Humphreys, N. J.; Douglas, A. E. (1997). "Partitioning of symbiotic bacteria between generations of an insect: a quantitative study of a Buchnera sp. in the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum) reared at different temperatures". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 63 (8): 3294–3296. doi:10.1128/AEM.63.8.3294-3296.1997. PMC 1389233. PMID 16535678.

- Liere, Heidi; Jackson, Doug; Vandermeer, John; Wilby, Andrew (20 September 2012). "Ecological Complexity in a Coffee Agroecosystem: Spatial Heterogeneity, Population Persistence and Biological Control". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e45508. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...745508L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0045508. PMC 3447771. PMID 23029061.

- Odum, E. P.; Barrett, G. W. (2005). Fundamentals of Ecology. Brooks Cole. p. 598. ISBN 978-0-534-42066-6.

- Steward T.A. Pickett; Jurek Kolasa; Clive G. Jones (1994). Ecological Understanding: The Nature of Theory and the Theory of Nature. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-554720-8.

- O'Neill, D. L.; Deangelis, D. L.; Waide, J. B.; Allen, T. F. H. (1986). A Hierarchical Concept of Ecosystems. Princeton University Press. p. 253. ISBN 0-691-08436-X.

- Nachtomy, Ohad; Shavit, Ayelet; Smith, Justin (2002). "Leibnizian organisms, nested individuals, and units of selection". Theory in Biosciences. 121 (2): 205–230. doi:10.1007/s12064-002-0020-9.

- Holling, C. S. (2004). "Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems". Ecosystems. 4 (5): 390–405. doi:10.1007/s10021-001-0101-5.

- Levin, S. A. (1999). Fragile Dominion: Complexity and the Commons. Reading, MA: Perseus Books. ISBN 978-0-7382-0319-5.