Community health

Community health is a branch of public health which focuses on people and their role as determinants of their own and other people's health in contrast to environmental health, which focuses on the physical environment and its impact on people's health.

Community health is a major field of study within the medical and clinical sciences which focuses on the maintenance, protection, and improvement of the health status of population groups and communities. It is a distinct field of study that may be taught within a separate school of public health or environmental health. The WHO defines community health as:

environmental, social, and economic resources to sustain emotional and physical well being among people in ways that advance their aspirations and satisfy their needs in their unique environment.[1]

Medical interventions that occur in communities can be classified as three categories: primary healthcare, secondary healthcare, and tertiary healthcare. Each category focuses on a different level and approach towards the community or population group. In the United States, community health is rooted within primary healthcare achievements.[2] Primary healthcare programs aim to reduce risk factors and increase health promotion and prevention. Secondary healthcare is related to "hospital care" where acute care is administered in a hospital department setting. Tertiary healthcare refers to highly specialized care usually involving disease or disability management.

The success of community health programmes relies upon the transfer of information from health professionals to the general public using one-to-one or one to many communication (mass communication). The latest shift is towards health marketing.

Measuring community health

Community health is generally measured by geographical information systems and demographic data. Geographic information systems can be used to define sub-communities when neighborhood location data is not enough.[3] Traditionally community health has been measured using sampling data which was then compared to well-known data sets, like the National Health Interview Survey or National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.[4] With technological development, information systems could store more data for small scale communities, cities, and towns; as opposed to census data that only generalizes information about small populations based on the overall population. Geographical information systems (GIS) can give more precise information of community resources, even at neighborhood levels.[5] The ease of use of geographic information systems (GIS), advances in multilevel statistics, and spatial analysis methods makes it easier for researchers to procure and generate data related to the built environment.[6]

Social media can also play a big role in health information analytics.[7] Studies have found social media being capable of influencing people to change their unhealthy behaviors and encourage interventions capable of improving health status.[7] Social media statistics combined with geographical information systems (GIS) may provide researchers with a more complete image of community standards for health and well being.[8][9]

Categories of community health

Primary healthcare and primary prevention

Community based health promotion emphasizes primary prevention and population based perspective (traditional prevention).[10] It is the goal of community health to have individuals in a certain community improve their lifestyle or seek medical attention. Primary healthcare is provided by health professionals, specifically the ones a patient sees first that may refer them to secondary or tertiary care.

Primary prevention refers to the early avoidance and identification of risk factors that may lead to certain diseases and disabilities. Community focused efforts including immunizations, classroom teaching, and awareness campaigns are all good examples of how primary prevention techniques are utilized by communities to change certain health behaviors. Prevention programs, if carefully designed and drafted, can effectively prevent problems that children and adolescents face as they grow up.[11] This finding also applies to all groups and classes of people. Prevention programs are one of the most effective tools health professionals can use to significantly impact individual, population, and community health.[11]

Secondary healthcare and secondary prevention

Community health can also be improved with improvements in individuals' environments. Community health status is determined by the environmental characteristics, behavioral characteristics, social cohesion in the environment of that community.[12] Appropriate modifications in the environment can help to prevent unhealthy behaviors and negative health outcomes.

Secondary prevention refers to improvements made in a patient's lifestyle or environment after the onset of disease or disability. This sort of prevention works to make life easier for the patient, since it's too late to prevent them from their current disease or disability. An example of secondary prevention is when those with occupational low back pain are provided with strategies to stop their health status from worsening; the prospects of secondary prevention may even hold more promise than primary prevention in this case.[13]

Chronic disease self management programs

Chronic diseases has been a growing phenomena within recent decades, affecting nearly 50% of adults within the US in 2012.[14] Such diseases include asthma, arthritis, diabetes, and hypertension. While they are not directly life-threatening, they place a significant burden on daily lives, affecting quality of life for the individual, their families, and the communities they live in, both socially and financially. Chronic diseases are responsible for an estimated 70% of healthcare expenditures within the US, spending nearly $650 billion per year.

With steadily growing numbers, many community healthcare providers have developed self-management programs to assist patients in properly managing their own behavior as well as making adequate decisions about their lifestyle.[15] Separate from clinical patient care, these programs are facilitated to further educate patients about their health conditions as a means to adopt health-promoting behaviors into their own lifestyle.[16] Characteristics of these programs include:

- grouping patients with similar chronic diseases to discuss disease-related tasks and behaviors to improve overall health

- improving patient responsibility through daily disease-monitoring

- inexpensive and widely known Chronic Disease self-management programs are structured to help improve overall patient health and quality of life as well as utilize less healthcare resources, such as physician visits and emergency care.[17][18]

Furthermore, better self-monitoring skills can help patients effectively and efficiently make better use of healthcare professionals' time, which can result in better care.[19] Many self-management programs either are conducted through a health professional or a peer diagnosed with a certain chronic disease trained by health professionals to conduct the program. No significant differences have been reported comparing the effectiveness of both peer-led versus professional led self-management programs.[18]

There has been a lot of debate regarding the effectiveness of these programs and how well they influence patient behavior and understanding their own health conditions. Some studies argue that self-management programs are effective in improving patient quality of life and decreasing healthcare expenditures and hospital visits. A 2001 study assessed health statuses through healthcare resource utilizations and self-management outcomes after 1 and 2 years to determine the effectiveness of chronic disease self-management programs. After analyzing 800 patients diagnosed with various types of chronic conditions, including heart disease, stroke, and arthritis, the study found that after the 2 years, there was a significant improvement in health status and fewer emergency department and physician visits (also significant after 1 year). They concluded that these low-cost self-management programs allowed for less healthcare utilization as well as an improvement in overall patient health.[20] Another study in 2003 by the National Institute for Health Research analyzed a 7-week chronic disease self-management program in its cost-effectiveness and health efficacy within a population over 18 years of age experiencing one or more chronic diseases. They observed similar patterns, such as an improvement in health status, reduced number of visits to the emergency department and to physicians, shorter hospital visits. They also noticed that after measuring unit costs for both hospital stays ($1000) and emergency department visits ($100), the study found the overall savings after the self-management program resulted in nearly $489 per person.[21] Lastly, a meta-analysis study in 2005 analyzed multiple chronic disease self-management programs focusing specifically on hypertension, osteoarthritis, and diabetes mellitus, comparing and contrasting different intervention groups. They concluded that self-management programs for both diabetes and hypertension produced clinically significant benefits to overall health.[15]

On the other hand, there are a few studies measuring little significance of the effectiveness of chronic disease self-management programs. In the previous 2005 study in Australia, there was no clinical significance in the health benefits of osteoarthritis self-management programs and cost-effectiveness of all of these programs.[15] Furthermore, in a 2004 literature review analyzing the variability of chronic disease self-management education programs by disease and their overlapping similarities, researchers found "small to moderate effects for selected chronic diseases," recommending further research being conducted.[16]

Some programs are looking to integrate self-management programs into the traditional healthcare system, specifically primary care, as a way to incorporate behavioral improvements and decrease the increased patient visits with chronic diseases.[22] However, they have argued that severe limitations hinder these programs from acting its full potential. Possible limitations of chronic disease self-management education programs include the following:[19]

- underrepresentation of minority cultures within programs

- lack of medical/health professional (particularly primary care) involvement in self-management programs

- low profile of programs within community

- lack of adequate funding from federal/state government

- low participation of patients with chronic diseases in program

- uncertainty of effectiveness/reliability of programs

Tertiary healthcare

In tertiary healthcare, community health can only be affected with professional medical care involving the entire population. Patients need to be referred to specialists and undergo advanced medical treatment. In some countries, there are more sub-specialties of medical professions than there are primary care specialists.[12] Health inequalities are directly related to social advantage and social resources.[12]

| Conventional ambulatory medical care in clinics or outpatient departments | Disease control programmes | People-centred primary care |

|---|---|---|

| Focus on illness and cure | Focus on priority diseases | Focus on health needs |

| Relationship limited to the moment of consultation | Relationship limited to programme implementation | Enduring personal relationship |

| Episodic curative care | Programme-defined disease control interventions | Comprehensive, continuous and personcentred care |

| Responsibility limited to effective and safe advice to the patient at the moment of consultation | Responsibility for disease-control targets among the target population | Responsibility for the health of all in the community along the life cycle; responsibility for tackling determinants of ill-health |

| Users are consumers of the care they purchase | Population groups are targets of disease-control interventions | People are partners in managing their own health and that of their community |

Challenges and difficulties with community health

The complexity of community health and its various problems can make it difficult for researchers to assess and identify solutions. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a unique alternative that combines community participation, inquiry, and action.[25] Community-based participatory research (CBPR) helps researchers address community issues with a broader lens and also works with the people in the community to find culturally sensitive, valid, and reliable methods and approaches.[25]

Other issues involve access and cost of medical care. A great majority of the world does not have adequate health insurance.[26] In low-income countries, less than 40% of total health expenditures are paid for by the public/government.[26] Community health, even population health, is not encouraged as health sectors in developing countries are not able to link the national authorities with the local government and community action.[26]

In the United States, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) changed the way community health centers operate and the policies that were in place, greatly influencing community health.[27] The ACA directly affected community health centers by increasing funding, expanding insurance coverage for Medicaid, reforming the Medicaid payment system, appropriating $1.5 billion to increase the workforce and promote training.[27] The impact, importance, and success of the Affordable Care Act is still being studied and will have a large impact on how ensuring health can affect community standards on health and also individual health.

Ethnic disparities in health statuses among different communities is also a cause of concern. Community coalition-driven interventions may bring benefits to this segment of society.[28]

Community health in the Global South

Access to community health in the Global South is influenced by geographic accessibility (physical distance from the service delivery point to the user), availability (proper type of care, service provider, and materials), financial accessibility (willingness and ability of users to purchase services), and acceptability (responsiveness of providers to social and cultural norms of users and their communities).[29] While the epidemiological transition is shifting disease burden from communicable to non communicable conditions in developing countries, this transition is still in an early stage in parts of the Global South such as South Asia, the Middle East, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[30] Two phenomena in developing countries have created a "medical poverty trap" for underserved communities in the Global South — the introduction of user fees for public healthcare services and the growth of out-of-pocket expenses for private services.[31] The private healthcare sector is being increasingly utilized by low and middle income communities in the Global South for conditions such as malaria, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted infections.[32] Private care is characterized by more flexible access, shorter waiting times, and greater choice. Private providers that serve low-income communities are often unqualified and untrained. Some policymakers recommend that governments in developing countries harness private providers to remove state responsibility from service provision.[32]

Community development is frequently used as a public health intervention to empower communities to obtain self-reliance and control over the factors that affect their health.[33] Community health workers are able to draw on their firsthand experience, or local knowledge, to complement the information that scientists and policy makers use when designing health interventions.[34] Interventions with community health workers have been shown to improve access to primary healthcare and quality of care in developing countries through reduced malnutrition rates, improved maternal and child health and prevention and management of HIV/AIDS.[35] Community health workers have also been shown to promote chronic disease management by improving the clinical outcomes of patients with diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular diseases.[35]

Slum-dwellers in the Global South face threats of infectious disease, non-communicable conditions, and injuries due to violence and road traffic accidents.[36] Participatory, multi-objective slum upgrading in the urban sphere significantly improves social determinants that shape health outcomes such as safe housing, food access, political and gender rights, education, and employment status. Efforts have been made to involve the urban poor in project and policy design and implementation. Through slum upgrading, states recognize and acknowledge the rights of the urban poor and the need to deliver basic services. Upgrading can vary from small-scale sector-specific projects (i.e. water taps, paved roads) to comprehensive housing and infrastructure projects (i.e. piped water, sewers). Other projects combine environmental interactions with social programs and political empowerment. Recently, slum upgrading projects have been incremental to prevent the displacement of residents during improvements and attentive to emerging concerns regarding climate change adaptation. By legitimizing slum-dwellers and their right to remain, slum upgrading is an alternative to slum removal and a process that in itself may address the structural determinants of population health.[36]

Academic resources

- Journal of Urban Health, Springer. ISSN 1468-2869 (electronic) ISSN 1099-3460 (paper).

- International Quarterly of Community Health Education, Sage Publications. ISSN 1541-3519 (electronic), ISSN 0272-684X (paper).

- Global Public Health, Informa Healthcare. ISSN 1744-1692 (paper).

- Journal of Community Health, Springer. ISSN 1573-3610.

- Family and Community Health, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISSN 0160-6379 (electronic).

- Health Promotion Practice, Sage Publications. ISSN 1552-6372 (electronic) ISSN 1524-8399 (paper).

- Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, Sage Publications. ISSN 1758-1060 (electronic) ISSN 1355-8196 (paper).

- BMC Health Sciences Research, Biomed Central. ISSN 1472-6963 (electronic).

- Health Services Research, Wiley-Blackwell. ISSN 1475-6773 (electronic).

- Health Communication and Literacy: An Annotated Bibliography, Centre for Literacy of Quebec. ISBN 0968103456.

See also

References

- "A discussion document on the concept and principles of health promotion". Health Promotion. 1 (1): 73–6. May 1986. doi:10.1093/heapro/1.1.73. PMID 10286854.

- Goodman RA, Bunnell R, Posner SF (October 2014). "What is "community health"? Examining the meaning of an evolving field in public health". Preventive Medicine. 67 Suppl 1: S58–61. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.07.028. PMC 5771402. PMID 25069043.

- Elias Mpofu, PhD (2014-12-08). Community-oriented health services : practices across disciplines. Mpofu, Elias. New York, NY. ISBN 9780826198181. OCLC 897378689.

- "Chapter 36. Introduction to Evaluation | Community Tool Box". ctb.ku.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- Pearce J, Witten K, Bartie P (May 2006). "Neighbourhoods and health: a GIS approach to measuring community resource accessibility". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 60 (5): 389–95. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.043281. PMC 2563982. PMID 16614327.

- Thornton LE, Pearce JR, Kavanagh AM (July 2011). "Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to assess the role of the built environment in influencing obesity: a glossary". The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 8: 71. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-71. PMC 3141619. PMID 21722367.

- Korda H, Itani Z (January 2013). "Harnessing social media for health promotion and behavior change". Health Promotion Practice. 14 (1): 15–23. doi:10.1177/1524839911405850. PMID 21558472. S2CID 510123.

- Stefanidis A, Crooks A, Radzikowski J (2013-04-01). "Harvesting ambient geospatial information from social media feeds". GeoJournal. 78 (2): 319–338. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.452.3726. doi:10.1007/s10708-011-9438-2. ISSN 0343-2521.

- Ghosh DD, Guha R (2013). "What are we 'tweeting' about obesity? Mapping tweets with Topic Modeling and Geographic Information System". Cartography and Geographic Information Science. 40 (2): 90–102. doi:10.1080/15230406.2013.776210. PMC 4128420. PMID 25126022.

- Merzel C, D'Afflitti J (April 2003). "Reconsidering community-based health promotion: promise, performance, and potential". American Journal of Public Health. 93 (4): 557–74. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.4.557. PMC 1447790. PMID 12660197.

- Nation M, Crusto C, Wandersman A, Kumpfer KL, Seybolt D, Morrissey-Kane E, Davino K (2003). "What works in prevention. Principles of effective prevention programs". The American Psychologist. 58 (6–7): 449–56. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.468.7226. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.58.6-7.449. PMID 12971191.

- Barbara S (1998). Primary care : balancing health needs, services, and technology (Rev. ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195125436. OCLC 38216563.

- Frank JW, Brooker AS, DeMaio SE, Kerr MS, Maetzel A, Shannon HS, Sullivan TJ, Norman RW, Wells RP (December 1996). "Disability resulting from occupational low back pain. Part II: What do we know about secondary prevention? A review of the scientific evidence on prevention after disability begins". Spine. 21 (24): 2918–29. doi:10.1097/00007632-199612150-00025. PMID 9112717.

- "Chronic Disease Overview | Publications | Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2017-10-02. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- Chodosh J, Morton SC, Mojica W, Maglione M, Suttorp MJ, Hilton L, Rhodes S, Shekelle P (September 2005). "Meta-analysis: chronic disease self-management programs for older adults". Annals of Internal Medicine. 143 (6): 427–38. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-6-200509200-00007. PMID 16172441.

- Warsi A, Wang PS, LaValley MP, Avorn J, Solomon DH (2004-08-09). "Self-management education programs in chronic disease: a systematic review and methodological critique of the literature". Archives of Internal Medicine. 164 (15): 1641–9. doi:10.1001/archinte.164.15.1641. PMID 15302634.

- Bene BA, O'Connor S, Mastellos N, Majeed A, Fadahunsi KP, O'Donoghue J (June 2019). "Impact of mobile health applications on self-management in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: protocol of a systematic review". BMJ Open. 9 (6): e025714. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025714. PMC 6597642. PMID 31243029.

- Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, Brown BW, Bandura A, Ritter P, et al. (January 1999). "Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial". Medical Care. 37 (1): 5–14. doi:10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. JSTOR 3767202. PMID 10413387. S2CID 6011270.

- Jordan, Joanne (November 15, 2006). "Chronic disease self-management education programs: challenges ahead" (PDF). Medical Journal of Australia. 186 (2): 84–87. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb00807.x.

- Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, Sobel DS, Brown BW, Bandura A, et al. (November 2001). "Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes". Medical Care. 39 (11): 1217–23. doi:10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. JSTOR 3767514. PMID 11606875. S2CID 36581025.

- Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter PL, Laurent D, Hobbs M (November 2001). "Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease". Effective Clinical Practice. 4 (6): 256–62. PMID 11769298.

- Leppin AL, Schaepe K, Egginton J, Dick S, Branda M, Christiansen L, Burow NM, Gaw C, Montori VM (January 2018). "Integrating community-based health promotion programs and primary care: a mixed methods analysis of feasibility". BMC Health Services Research. 18 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2866-7. PMC 5793407. PMID 29386034.

- "Chapter 3: Primary care: putting people first". www.who.int. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

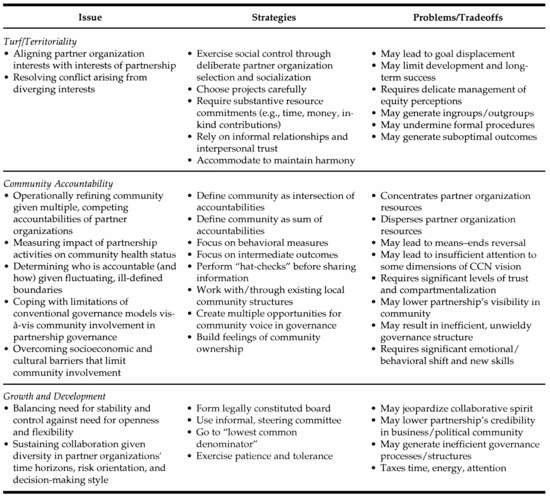

- Weiner BJ, Alexander JA (1998). "The challenges of governing public-private community health partnerships". Health Care Management Review. 23 (2): 39–55. doi:10.1097/00004010-199804000-00005. PMID 9595309.

- Minkler M (June 2005). "Community-based research partnerships: challenges and opportunities". Journal of Urban Health. 82 (2 Suppl 2): ii3-12. doi:10.1093/jurban/jti034. PMC 3456439. PMID 15888635.

- Organization, World Health (2016-06-08). World health statistics. 2016, Monitoring health for the SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland. ISBN 978-9241565264. OCLC 968482612.

- Rosenbaum SJ, Shin P, Jones E, Tolbert J (2010). "Community Health Centers: Opportunities and Challenges of Health Reform". Health Sciences Research Commons.

- Anderson LM, Adeney KL, Shinn C, Safranek S, Buckner-Brown J, Krause LK (15 June 2015). "Community coalition-driven interventions to reduce health disparities among racial and ethnic minority populations". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (6): CD009905. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009905.pub2. PMID 26075988.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Peters DH, Garg A, Bloom G, Walker DG, Brieger WR, Rahman MH (2008-07-25). "Poverty and access to health care in developing countries". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1136 (1): 161–71. Bibcode:2008NYASA1136..161P. doi:10.1196/annals.1425.011. PMID 17954679.

- Orach, Christopher (October 2009). "Health equity: challenges in low income countries". African Health Sciences. 9: 549–551. PMC 2877288. PMID 20589106.

- Whitehead M, Dahlgren G, Evans T (September 2001). "Equity and health sector reforms: can low-income countries escape the medical poverty trap?". Lancet. 358 (9284): 833–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05975-X. PMID 11564510.

- Zwi AB, Brugha R, Smith E (September 2001). "Private health care in developing countries". BMJ. 323 (7311): 463–4. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7311.463. PMC 1121065. PMID 11532823.

- Hossain SM, Bhuiya A, Khan AR, Uhaa I (April 2004). "Community development and its impact on health: South Asian experience". BMJ. 328 (7443): 830–3. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7443.830. PMC 383386. PMID 15070644.

- Corburn, Jason. (2005). Street science : community knowledge and environmental health justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262270809. OCLC 62896609.

- Javanparast S, Windle A, Freeman T, Baum F (July 2018). "Community Health Worker Programs to Improve Healthcare Access and Equity: Are They Only Relevant to Low- and Middle-Income Countries?". International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 7 (10): 943–954. doi:10.15171/ijhpm.2018.53. PMC 6186464. PMID 30316247.

- Corburn J, Sverdlik A (March 2017). "Slum Upgrading and Health Equity". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 14 (4): 342. doi:10.3390/ijerph14040342. PMC 5409543. PMID 28338613.

Further reading

- Agafonow, Alejandro (2018). "Setting the bar of social enterprise research high. Learning from medical science". Social Science & Medicine. 214: 49–56. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.020. PMID 30149199.

- John Sanbourne Bockoven (1963). Moral Treatment in American Psychiatry, New York: Springer Publishing Co.