Beaver

The beaver (genus Castor) is a large, primarily nocturnal, semiaquatic rodent. Castor includes two extant species, the North American beaver (Castor canadensis) (native to North America) and Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) (Eurasia).[1] Beavers are known for building dams, canals, and lodges (homes). They are the second-largest rodent in the world (after the capybara). Their colonies create one or more dams to provide still, deep water to protect against predators, and to float food and building material. The North American beaver population was once more than 60 million, but as of 1988 was 6–12 million. A similar trend occurred in Europe, with only around 1200 individuals remaining at the turn of the 20th Century. This population decline is the result of extensive hunting for fur, for glands used as medicine and perfume, and because the beavers' harvesting of trees and flooding of waterways may interfere with other land uses.[2]

| Beaver | |

|---|---|

| |

| North American beaver (Castor canadensis) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Castoridae |

| Subfamily: | Castorinae |

| Genus: | Castor Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Species | |

|

C. fiber – Eurasian beaver | |

General

Beavers, along with pocket gophers and kangaroo rats, are castorimorph rodents, a suborder of rodents mostly restricted to North America. Although just two closely related species exist today, beavers have a long fossil history in the Northern Hemisphere beginning in the Eocene, and many species of giant beaver existed until quite recently, such as Trogontherium in Europe, and Castoroides in North America.

Beavers are known for their natural trait of building dams on rivers and streams, and building their homes (known as "lodges") in the resulting pond. Beavers also build canals to float building materials that are difficult to haul over land.[3][4] They use powerful front teeth to cut trees and other plants that they use both for building and for food. In the absence of existing ponds, beavers must construct dams before building their lodges. First they place vertical poles, then fill between the poles with a crisscross of horizontally placed branches. They fill in the gaps between the branches with a combination of weeds and mud until the dam impounds sufficient water to surround the lodge.

They are known for their alarm signal: when startled or frightened, a swimming beaver will rapidly dive while forcefully slapping the water with its broad tail, audible over great distances above and below water. This serves as a warning to beavers in the area. Once a beaver has sounded the alarm, nearby beavers will dive and may not reemerge for some time. Beavers are slow on land, but are good swimmers, and can stay under water for as long as 15 minutes.

Beavers do not hibernate, but store sticks and logs in a pile in their ponds, eating the underbark. Some of the pile is generally above water and accumulates snow in the winter. This insulation of snow often keeps the water from freezing in and around the food pile, providing a location where beavers can breathe when outside their lodge.

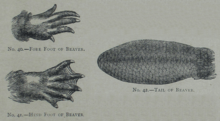

Beavers have webbed hind-feet, and a broad, scaly tail. They have poor eyesight, but keen senses of hearing, smell, and touch. A beaver's teeth grow continuously so they will not be worn down by chewing on wood.[5] Their four incisors are composed of hard orange enamel on the front and a softer dentin on the back. The chisel-like ends of incisors are maintained by their self-sharpening wear pattern. The enamel in a beaver's incisors contains iron and is more resistant to acid than enamel in the teeth of other mammals.[6]

Beavers continue to grow throughout their lives. Adult specimens weighing over 25 kg (55 lb) are not uncommon. Females are as large as or larger than males of the same age, which is uncommon among mammals. Beavers live up to 24 years of age in the wild.

Etymology

The English word "beaver" comes from the Old English word beofor or befer (recorded earlier as bebr), which in turn sprang from the Proto-Germanic root *bebruz. Cognates in other Germanic languages include the Old Saxon bibar, the Old Norse bjorr, the Middle Dutch and Dutch bever, the Low German bever, the Old High German bibar and the Modern German Biber. The Proto-Germanic word in turn came from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) word *bhebhrus, a reduplication of the PIE root *bher-, meaning "brown" or "bright", whose own descendants now include the Lithuanian bebras and the Czech bobr, as well as the Germanic forms.[7]

Species

The North American and Eurasian beavers are the only extant members of the family Castoridae, contained within the genus, Castor. Genetic research has shown the modern European and North American beaver populations to be distinct species and that hybridization is unlikely. Although superficially similar to each other, there are several important differences between the two species. Eurasian beavers tend to be slightly larger, with larger, less rounded heads, longer, narrower muzzles, thinner, shorter and lighter underfur, narrower, less oval-shaped tails and shorter shin bones, making them less capable of bipedal locomotion than the North American species. Eurasian beavers have longer nasal bones than their North American cousins, with the widest point being at the end of the snout for the former, and in the middle for the latter. The nasal opening for the Eurasian species is triangular, unlike that of the North American, which is square. The foramen magnum is rounded in the Eurasian beaver and triangular in the North American. The anal glands of the Eurasian beaver are larger and thin-walled with a large internal volume compared to that of the North American species. The guard hairs of the Eurasian beaver have a longer hollow medulla at their tips. Fur colour is also different. Overall, 66% of Eurasian beavers have pale brown or beige fur, 20% have reddish brown, nearly 8% are brown and only 4% have blackish coats. In North American beavers, 50% have pale brown fur, 25% are reddish brown, 20% are brown and 6% are blackish.[8]

The two species are not genetically compatible. North American beavers have 40 chromosomes, while Eurasian beavers have 48. More than 27 attempts were made in Russia to hybridize the two species, with one breeding between a male North American beaver and a female European resulting in a single stillborn kit. These factors make interspecific breeding unlikely in areas where the two species' ranges overlap.[8]

Eurasian beaver

The Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) was hunted nearly to extinction in Europe, both for fur and for castoreum, a secretion from its scent gland believed to have medicinal properties. However, the beaver is now being re-introduced throughout Europe. Several thousand live on the Elbe and the Rhône and in parts of Scandinavia. A thriving community lives in northeast Poland, and the Eurasian beaver also returned to the Morava River banks in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. They have been reintroduced in Scotland (Knapdale),[9] Bavaria, Austria, Netherlands, Serbia (Zasavica bog), Denmark (West Jutland) and Bulgaria and are spreading to new locations. The beaver became extinct in Great Britain in the sixteenth century: Giraldus Cambrensis reported in 1188 (Itinerarium ii.iii) that it was to be found only in the Teifi in Wales and in one river in Scotland, though his observations are clearly second hand. In 2001, Kent Wildlife Trust successfully introduced a family of beavers at Ham Fen, the last remaining ancient fenland in the county close to the town of Sandwich; these are now established and are breeding. In October 2005, six Eurasian beavers were reintroduced to Britain in Lower Mill Estate in Gloucestershire; in July 2007 a colony of four Eurasian beavers was established at Martin Mere in Lancashire,[10] and a small population of probably Eurasian beavers is being monitored in Devon.[11] A trial re-introduction occurred in Scotland in May 2009. Feasibility studies for a reintroduction to Wales are at an advanced stage and a preliminary study for a reintroduction of beavers to the wild in England has recently been published.[12][13]

North American beaver

The North American beaver (Castor canadensis), also called the Canadian beaver (which is also the name of a subspecies), American beaver, or simply beaver in North America, is native to Canada, much of the United States and the states of Sonora and Chihuahua in northern Mexico.[14][15][16] This species was introduced to the Argentine and Chilean Tierra del Fuego, as well as Finland, France, Poland and Russia.[17][18]

The North American beavers prefer the (inner) bark of aspen and poplar but will also take birch, maple, willow, alder, black cherry, red oak, beech, ash, hornbeam and occasionally pine and spruce.[19] They will also eat cattails, water lilies and other aquatic vegetation, especially in the early spring (and contrary to widespread belief,[20] they do not eat fish).

These animals are often trapped for their fur. During the early 19th century, trapping eliminated this animal from large portions of its original range. Beaver furs were used to make clothing and top-hats. Much of the early exploration of North America was driven by the quest for this animal's fur.[21][22] [23] Native peoples and early settlers also ate this animal's meat. The Federal Lacey Act was passed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1900 which forbade any take of wildlife or plants in violation of Indian, State or foreign law.[24] Through trap and transfer and habitat conservation, beavers made a nearly complete recovery by the 1940s.The current beaver population has been estimated to be 10 to 15 million; one estimate claims there may have been at one time as many as 90 million.[25]

Habitat

The primary habitat of the beaver is the riparian zone, inclusive of stream bed. The actions of beavers for hundreds of thousands of years [26] in the Northern Hemisphere have kept these watery systems healthy and in good repair. However, some beavers inhabit the intertidal zone in river estuaries, building dams to trap high tides in a beaver pond for similar purposes.[27][28]

The beaver works as a keystone species in an ecosystem by creating wetlands that are used by many other species. Next to humans, no other extant animal appears to do more to shape its landscape.[29] Beavers potentially even affect climate change.[30]

Beavers fell trees for several reasons. They fell large mature trees, usually in strategic locations, to form the basis of a dam, but European beavers tend to use small diameter (<10 cm) trees for this purpose. Beavers fell small trees, especially young second-growth trees, for food.

Broadleaved trees re-grow as a coppice, providing easy-to-reach stems and leaves for food in subsequent years. Ponds created by beavers can also kill some tree species by drowning, but this creates standing dead wood, which is very important for a wide range of animals and plants.[31]

Dams

Beaver dams are created as a protection against predators, such as coyotes, wolves and bears, and to provide easy access to food during winter. Beavers always work at night and are prolific builders, carrying mud and stones with their fore-paws and timber between their teeth. Because of this, destroying a beaver dam without removing the beavers is difficult, especially if the dam is downstream of an active lodge. Beavers can rebuild such primary dams overnight, though they may not defend secondary dams as vigorously. Beavers may create a series of dams along a river.

Lodges

The ponds created by well-maintained dams help isolate the beavers' homes, which are called lodges. These are created from severed branches and mud. The beavers cover their lodges late each autumn with fresh mud, which freezes when frosts arrive. The mud becomes almost as hard as stone, thereby preventing wolves and wolverines from penetrating the lodge.

The lodge has underwater entrances, which makes entry nearly impossible for any other animal, although muskrats have been seen living inside beaver lodges with the beavers who made them.[32] Only a small amount of the lodge is actually used as a living area. Beavers dig out their dens with underwater entrances after they finish building the dams and lodge structures. There are typically two dens within the lodge, one for drying off after exiting the water and another, drier one in which the family lives.

Beaver lodges are constructed with the same materials as the dams, with little order or regularity of structure. They seldom house more than four adults and six to eight juveniles. Some larger lodges have one or more partitions, but these are only posts of the main building left by the builders to support the roof. Usually, the dens have no connection with each other except by water.

When the ice breaks up in spring, beavers usually leave their lodges and roam until just before autumn, when they return to their old lodges and gather their winter stock of wood. They seldom begin to repair the lodges until the frost sets in, and rarely finish the outer coating until the cold becomes severe. When they erect a new lodge, they fell the wood early in summer but seldom begin building until nearly the end of August.[33]

Water quality and beavers

Beaver ponds, and the wetlands that succeed them, remove sediments and pollutants from waterways, including total suspended solids, total nitrogen, phosphates, carbon and silicates.[34][35]

The term "beaver fever" is a misnomer coined by the American press in the 1970s, following findings that the parasite Giardia lamblia, which causes Giardiasis, is carried by beavers. However, further research has shown that many animals and birds carry this parasite, and the major source of water contamination is other humans.[36][37][38] Norway has many beavers but has not historically had giardia, and New Zealand has giardia but no beaver. Recent concerns point to domestic animals as a significant vector of giardia, with young calves in dairy herds testing as high as 100% positive for giardia.[39] In addition, fecal coliform and streptococci bacteria excreted into streams by grazing cattle have been shown to be reduced by beaver ponds, where the bacteria are trapped in bottom sediments.[40]

Urban beavers in North America

Beaver populations in Canadian cities have seen a resurgence in numbers in the decades since the decline of the fur trade.[42][43][44] In 2016, approximately 200 beavers live within the city limits of Calgary, while an estimated 100 beavers live in Winnipeg.[45] In the same year, it was estimated that several dozen beavers live within the city limits of Vancouver.[45] Toronto does not keep count of its local beaver population,[45] although an estimate from 2001 places its local beaver population at several hundred.[44]

Several cities in the United States have seen the reintroduction of beavers within their city limits. For example, beavers were trapped to near extirpation and had not been seen in New York City since the early 1800s.[46] It was after 200 years that a beaver returned to New York City, making its home along the Bronx River.[47]

In Chicago, several beavers have returned and made a home near the Lincoln Park's North Pond. The "Lincoln Park beaver" has not been as well received by the Chicago Park District and the Lincoln Park Conservancy, which was concerned over damage to trees in the area. In March 2009, they hired an exterminator to remove a beaver family using live traps, and accidentally killed the mother when it got caught in a snare and drowned.[48]

Outside San Francisco, in downtown Martinez, California, a male and female beaver arrived in Alhambra Creek in 2006.[49] The Martinez beavers built a dam 30 feet wide and at one time six feet high, and chewed through half the willows and other creekside landscaping the city planted as part of its $9.7 million 1999 flood-improvement project. When the city council wanted to remove the beavers because of fears of flooding, local residents organized to protect them, forming an organization called "Worth a Dam".[50]

As an introduced non-native species

In the 1940s, beavers were brought from northern Manitoba in Canada to the island of Tierra Del Fuego in southern Chile and Argentina, for commercial fur production. However, the project failed and the beavers, ten pairs, were released into the wild. Having no natural predators in their new environment, they quickly spread throughout the island, and to other islands in the region, reaching a number of 100,000 individuals within just 50 years. They are now considered a serious invasive species in the region, due to their massive destruction of forest trees, and efforts are being made for their eradication.[51] The drastically different ecosystem has led to substantial environmental damage, as the ponds created by the beavers have no ecological purpose (wetlands do not form there as they do in the beavers' native territory) and there are no native, large predators. They have also been found to cross salt water to islands northward; a possible encroachment on the mainland has naturalists highly concerned.

In contrast, areas with introduced beaver were associated with increased populations of native puye fish (Galaxias maculatus), whereas the exotic brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) had negative effects on native stream fishes in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, Chile.[52]

Beavers are classed as a "prohibited new organism" under New Zealand's Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 1996, preventing them from legally being imported into the country.[53]

Social behavior

Family life

The basic units of beaver social organization are families consisting of an adult male and adult female in a monogamous pair and their kits and yearlings.[54] Beaver families can have as many as ten members in addition to the monogamous pair. Groups this size or close to this size build more lodges to live in while smaller families usually need only one.[54] However, large families in the Northern Hemisphere have been recorded living in one lodge. Beaver pairs mate for life; however, if a beaver's mate dies, it will partner with another one. Extra-pair copulations also occur.[54] In addition to being monogamous, both the male and female take part in raising offspring. They also both mark and defend the territory and build and repair the dam and lodge.[54] When young are born, they spend their first month in the lodge and their mother is the primary caretaker while their father maintains the territory. In the time after they leave the lodge for the first time, yearlings will help their parents build food caches in the fall and repair dams and lodges. Still, adults do the majority of the work and young beavers help their parents for reasons based on natural selection rather than kin selection. They are dependent on them for food and for learning life skills.[54] Young beavers spend most of their time playing but also copy their parents' behavior. However, while copying behavior helps imprint life skills in young beavers, it is not necessarily immediately beneficial for parents as the young beaver do not perform the tasks as well as the parents.[54]

Older offspring, which are around two years old, may also live in families and help their parents. In addition to helping build food caches and repairing the dam, two-year-olds will also help in feeding, grooming and guarding younger offspring.[54] Beavers also practice alloparental care, in which an older sibling may take over the parenting duties if the original parents die or are otherwise separated from them. This behavior is common and is seen in many other animal species, such as the elephant and fathead minnow.[55] While these helping two-year-olds help increase the chance of survival for younger offspring, they are not essential for the family, and two-year-olds stay and help their families only if there is a shortage of resources in times of food shortage, high population density, or drought.[54] When beavers leave their natal territories, they usually do not settle far.[56] Beavers can recognize their kin by detecting differences in anal gland secretion composition using their keen sense of smell.[57] Related beavers share more features in their anal gland secretion profile than unrelated beavers.[57] Being able to recognize kin is important for beaver social behavior, and it causes more tolerant behavior among neighboring beavers.[56]

Territories and spacing

Beavers maintain and defend territories, which are areas for feeding, nesting and mating.[54] They invest much energy in their territories, building their dams and becoming familiar with the area.[58] Beavers mark their territories by constructing scent mounts made of mud, debris and castoreum,[59] a urine based substance excreted through the beavers castor sacs between the pelvis and base of the tail.[58] These scent mounts are established on the border of the territory.[59] Once a beaver detects another scent in its territory, finding the intruder takes priority, even over food.[59] Because they invest so much energy in their territories, beavers are intolerant of intruders and the holder of the territory is more likely to escalate an aggressive encounter.[58] These encounters are often violent. To avoid such situations, a beaver marks its territory with as many scent mounds as possible, signaling to intruders that the territory holder has enough energy to maintain its territory and is thus able to put up a good defense. As such, territories with more scent mounts are avoided more often than ones with fewer mounts.[58] Scent marking increases in August during the dispersal of yearlings, in an attempt to prevent them from intruding on territories.[58] Beavers also exhibit a behavior known as the "dear enemy effect". A territory-holding beaver will investigate and become familiar with the scents of its neighbors.[56] As such they respond less aggressively to intrusions by their territorial neighbours than those made by non-territorial floaters or "strangers".[56]

Occurrences of beaver aggression towards humans have been reported. In April 2013, an angler, near Minkovichi in the Brest region of Belarus, died after being bitten twice on the leg by a wild Eurasian beaver.[60]

Environmental Hazards

Beavers use their teeth to gnaw at trees and once they fell the trees and shrubs they use the wood to build dams. These structures flood valleys and form lakes which then cause permafrost to thaw and release methane in Arctic areas.[61] As this gas is released to the atmosphere, climate change ensues. The beavers' recent migration and habitation in the Alaskan tundra is escalating this danger.[62]

Commercial uses

Both beaver testicles and castoreum, a bitter-tasting secretion with a slightly fetid odor contained in the castor sacs of male or female beaver, have been articles of trade for use in traditional medicine. Yupik medicine used dried beaver testicles like willow bark to relieve pain. Dried beaver testicles were also used as contraception.[63] Beaver testicles were used as medicine in Iraq and Iran during the tenth to nineteenth century.[64] Aesop's Fables describes beavers chewing off their testicles to preserve themselves from hunters, which is not possible because the beaver's testicles are inside its body. This belief, also recorded by Pliny the Elder, persisted in medieval bestiaries.[65]

European beavers (Castor fiber) were eventually hunted nearly to extinction in part for the production of castoreum, which was used as an analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic. Castoreum was described in the 1911 British Pharmaceutical Codex for use in dysmenorrhea and hysterical conditions (i.e. pertaining to the womb), for raising blood pressure and increasing cardiac output. The activity of castoreum has been credited to the accumulation of salicin from willow trees in the beaver's diet, which is transformed to salicylic acid and has an action very similar to aspirin.[66] Castoreum continues to be used in perfume production.[67]

Castoreum can be used as an enhancer of vanilla, strawberry and raspberry flavorings. It is sometimes added to frozen dairy, gelatins, candy, and fruit beverages. Due to the difficulty and expense in obtaining castoreum, it is very rarely used in common food products.[67][68]

Much of the early European exploration and trade of Canada was based on the quest for beaver.[69] The most valuable part of a beaver is its inner fur whose many minute barbs make it excellent for felting, especially for hats. In Canada a "made beaver" or castor gras that a native had worn or slept on was more valuable than a fresh skin since this tended to wear off the outer guard hairs.[70]

Trapping

.jpg)

Beavers have been trapped for millennia, and this continues to this day.[71] Beaver pelts were used for barter by Native Americans in the 17th century to gain European goods. They were then shipped back to Great Britain and France where they were made into clothing items. Widespread hunting and trapping of beavers led to their endangerment. Eventually, the fur trade declined due to decreasing demand in Europe and the takeover of trapping grounds to support the growing agriculture sector. A small resurgence in beaver trapping has occurred in some areas where there is an over-population of beaver; trapping is done when the fur is of value, and the remainder of the animal may be used as feed. In the 1976/1977 season, 500,000 beaver pelts were harvested in North America.[72]

In culture

In wider culture, the beaver is famed for its industriousness and its building skills. The English verb "to beaver" means to work hard and constantly.

Beverly or Beverley, a placename found at various locations in the English-speaking world and also commonly used as a first name, derives from Old English, combining the words befer ("beaver") and leah ("clearing").

The show Happy Tree Friends features Toothy and Handy who are beavers.

The animated Nickelodeon show The Angry Beavers features Daggett and Norbert.

The anthropomorphic Mr. and Mrs. Beaver have an important role in the plot of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, first part of C.S.Lewis' The Chronicles of Narnia.

The first Redwall book features an unnamed beaver who helps Constance the badger build a bow, the only one ever seen before the books shifted to focus on animals commonly native to the British Isles.

The 2014 American horror comedy film Zombeavers, directed by Jordan Rubin, follows a group of college students on a camping trip that are attacked by a swarm of zombie beavers.

As an emblem

National

The importance of the beaver in the development of Canada through the fur trade led to its official designation as the national animal in 1975. The animal has long been associated with Canada, appearing on the coat of arms of the Hudson's Bay Company in 1678.[73] It is depicted on the Canadian five-cent piece and was on the first pictorial postage stamp issued in the Canadian colonies in 1849 (the so-called "Three-Penny Beaver"). As a national symbol, the beaver was chosen to be the mascot of the 1976 Summer Olympics held in Montreal with the name "Amik" ("beaver" in Ojibwe). The beaver is also the symbol of many units and organizations within the Canadian Forces, such as on the cap badges of the Royal 22e Régiment, the Calgary Highlanders, the Royal Westminster Regiment and the Canadian Military Engineers. Toronto Police Services, London Police Service, Canadian Pacific Railway Police Service and Canadian Pacific Railway bear the beaver on their crest or coat of arms.

Others

The beaver is used as a mascot of several colleges and universities, often universities with heritages in engineering and forestry. Others who have used the beaver in their company or organizational symbol or as their mascot include:

- The Beaver (magazine)

- Beaver Buzz energy drink

- Beaver Lumber

- Bemidji State University

- Beverley, East Riding of Yorkshire, UK

- Buc-ee's, a chain of convenience stores in Texas

- Buena Vista University

- California Institute of Technology

- Canadian Pacific Railway

- City College of New York

- F.C. Paços de Ferreira

- Harper Creek High School (Battle Creek, Michigan)

- Huron University College

- The London School of Economics[74]

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology[75]

- McMaster University Society of Off-Campus Students

- Parks Canada

- New York City

- Oregon State University

- Roots Canada retail company

- St Anne's College, Oxford

- The State of New York

- The State of Oregon

- The University of Alberta Faculty of Engineering

- The University of Toronto

- Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission

- Wilfrid Laurier University

In dietary law

In the 17th century, based on a question raised by the Bishop of Quebec, the Roman Catholic Church ruled that beavers are fish (beaver flesh was a part of the Yuko[76] indigenous peoples' diet, prior to the Europeans' arrival[77]) for purposes of dietary law. Therefore, the general prohibition on the consumption of meat on Fridays did not apply to beaver meat.[78][79][80] The legal basis for the decision probably rests with the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas, which bases animal classification as much on habit as anatomy.[81] This is similar to the Church's classification of other semi-aquatic rodents, such as the capybara and muskrat.[82][83]

References

- Helgen, K.M. (2005). "Genus Castor". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 842–843. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Nowak, Ronald M. 1991. pp. 364–367. Walker's Mammals of the World Fifth Edition, vol. I. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- Salvesen, Sigvald (May 1928). "The Beaver in Norway". Journal of Mammalogy. 9 (2): 99–104. doi:10.2307/1373424. JSTOR 1373424.

- "Beaver Dams and Canals". animaltrail. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- "Beaver Biology". Beaver Solutions. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- Megan Fellman (February 12, 2015). "Making Teeth Tough: Beavers Show Way To Improve Our Enamel (Discovery could lead to better understanding of tooth decay process, early detection)". www.northwestern.edu. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- Kitchener, Andrew (2001). Beavers. Stowmarket: Whittet. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-873580-55-4.

- Carrell, Severin (May 26, 2008). "Beavers returning to UK after 400 years". The Guardian. London. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- "Beavers are back after 500 years". BBC News. July 11, 2007.

- Marshall, Claire (January 28, 2015). "'Mystery' beavers permitted to stay". BBC News. Retrieved January 18, 2017 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "MSN UK - Outlook.com formerly Hotmail, Skype, Bing and Latest News". Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- "Beavers could be released in 2009". BBC. December 24, 2007. Archived from the original on February 6, 2008.

- Juan Pablo Gallo-Reynoso, Gabriela Suarez-Gracida, Horacia Cabrera-Santiago, Elsa Coria-Galindo, Janitzio Egido-Villarreal, and Leo C. Ortiz (2002). "Status of beaver (Castor canadensis frondator) in Río Bavispe, Sonora, Mexico". Southwestern Naturalist. 47 (3): 501–504. doi:10.2307/3672516. JSTOR 3672516.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Karla Pelz Serrano, Eduardo Ponce Guevara, and Carlos A. López González. "Habitat and Conservation Status of the Beaver in the Sierra San Luis Sonora, México" (PDF). USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-36. Retrieved December 5, 2017.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- El Heraldo de Chihuahua (December 5, 2017). "Nice surprise: camera discovers that there are otters in Chihuahua". El Sol de Mexico.

- Christopher B. Anderson, María Vanessa Lencinas, Petra K. Wallem, Alejandro E. J. Valenzuela, Michael P. Simanonok and Guillermo Martinez Pastur (2013). "Engineering by an invasive species alters landscape-level ecosystem function, but does not affect biodiversity in freshwater systems". Diversity and Distributions. 20 (2): 1–9. doi:10.1111/ddi.12147.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Jean-Francois Ducroz, Michael Stubbe, Alexander P Saveljev, Dietrich Heideke, Rivcan Samjaa, Alius Ulevicius, Annegret Stubbe, and Walter Durka (2005). "Genetic Variation and Population Structure of the Eurasian Beaver Castor Fiber in Eastern Europe and Asia". Journal of Mammalogy. 86 (6): 1059–1067. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2005)86[1059:gvapso]2.0.co;2. JSTOR 4094529.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Müller-Schwarze, Dietland & Sun, Lixing (2003). The Beaver: Natural History of a Wetlands Engineer. Cornell University Press. pp. 67–75. ISBN 978-0-8014-4098-4.

- Young, Mary Taylor (August 13, 2007)."Colorado Division of Wildlife: Do Beavers Eat Fish?". Archived from the original on September 10, 2010. Retrieved 2015-05-18.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) wildlife.state.co.us

- Manifest Destiny: The Oregon Country and Westward Expansion Archived May 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Innis, Harold A. (1999). The Fur Trade in Canada: An Introduction to Canadian Economic History. Revised and reprinted. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8196-4.

- Idaho Museum of Natural History

- "Lacey Act". www.fws.gov. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- Seton-Thompson, cited in Sun, Lixing; Dietland Müller-Schwarze (2003). The Beaver: Natural History of a Wetlands Engineer. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4098-4. pp. 97–98; but note that to arrive at this figure he assumed a population density throughout the range equivalent to that in Algonquin Park

- NatureWorldNews (May 29, 2015). "New Beaver Species Discovered in Oregon". Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- Goldfarb, Ben (January 29, 2019). "The Gnawing Question of Saltwater Beavers". Hakai magazine. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- Hood, W. Gregory (February 16, 2012). "Beaver in Tidal Marshes: Dam Effects on Low-Tide Channel Pools and Fish Use of Estuarine Habitat" (PDF). Wetlands. 32 (3): 401–410. doi:10.1007/s13157-012-0294-8. Retrieved February 1, 2019.

- "Beaver (beavers 'second only to humans in their ability to manipulate and change their environment')". National Geographic. September 10, 2010. Retrieved October 6, 2019.

- Wohl, Ellen (2013). "Landscape-scale carbon storage associated with Beaver Dams". Geophysical Research Letters. 40 (14): 3631–3636. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.3631W. doi:10.1002/grl.50710.

- "Dead Wood for Wildlife (Wildlife Outreach Center)". Wildlife Outreach Center (Penn State Extension). Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- The Life of Mammals Episode 4, "Chisellers".

-

- David L. Correll; Thomas E. Jordan; Donald E. Weller (June 2000). "Beaver pond biogeochemical effects in the Maryland Coastal Plain". Biogeochemistry. 49 (3): 217–239. doi:10.1023/a:1006330501887. JSTOR 1469618.

- Sarah Muskopf (October 2007). The Effect of Beaver (Castor canadensis) Dam Removal on Total Phosphorus Concentration in Taylor Creek and Wetland, South Lake Tahoe, California (Thesis). Humboldt State University, Natural Resources. hdl:2148/264.

- Martin Gaywood; Dave Batty; Colin Galbraith (2008). "Reintroducing the European Beaver in Britain". British Wildlife. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- Erlandsen, S. L. & W. J. Bemrick (1988). Waterborne giardiasis: sources of Giardia cysts and evidence pertaining to their implication in human infection in P. M. Wallis and B. R. Hammond (ed.), Advances in Giardia research. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press. pp. 227–236.

- Erlandsen SL, Sherlock LA, Bemrick WJ, Ghobrial H, Jakubowski W (January 1990). "Prevalence of Giardia spp. in Beaver and Muskrat Populations in Northeastern States and Minnesota: Detection of Intestinal Trophozoites at Necropsy Provides Greater Sensitivity than Detection of Cysts in Fecal Samples". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 56 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1128/AEM.56.1.31-36.1990. PMC 183246. PMID 2178552. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- R. C. A. Thompson (November 2000). "Giardiasis as a re-emerging infectious disease and its zoonotic potential". International Journal for Parasitology. 30 (12–13): 1259–1267. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(00)00127-2. PMID 11113253.

- Quentin D. Skinner; John E. Speck; Michael Smith; John C. Adams (March 1984). "Stream Water Quality as Influenced by Beaver within Grazing Systems in Wyoming". Journal of Range Management. 37 (2): 142–146. doi:10.2307/3898902. JSTOR 3898902.

- "Trees in parks & ravines - beavers". 311 Toronto. City of Toronto. 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- Campbell, Meagan (July 5, 2017). "Canada's beaver problem". Maclean's. Rogers Digital Media. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- Smith, Kim (June 7, 2016). "'He's quite shy': Beaver sightings on the rise in Calgary". Global News. Corus Entertainment Inc. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- Mittelstaedt, Martin (March 5, 2001). "Leave it to beavers, they're loving the big-city life". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- McCutcheon, Andrew (February 2, 2016). "Vancouver's urban-beaver plan focuses on enhancing habitats". The Globe and Mail. The Woodbridge Company. Retrieved July 29, 2019.

- Peter Miller (September 2009). "Manhattan Before New York: When Henry Hudson first looked on Manhattan in 1609, what did he see?". National Geographic.

- "New York City Beaver Returns". Science Daily. December 20, 2008.

- Boehm, Kiersten (November 14, 2008). "Lincoln Park Beaver Relocated". Inside at Your News Chicago, Illinois Edition. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- Carolyn Jones (April 16, 2008). "Moment of truth for Martinez beavers". San Francisco Chronicle.

- "Worth a Dam website".

- "Argentina eager to rid island of beavers". CNN. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- Michelle C. Moorman; David B. Eggleston; Christopher B. Anderson; Andres Mansilla; Paul Szejner (2009). "Implications of Beaver Castor canadensis and Trout Introductions on Native Fish in the Cape Horn Biosphere Reserve, Chile". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 138 (2): 306–313. doi:10.1577/T08-081.1.

- "Hazardous Substances and New Organisms Act 2003 – Schedule 2 Prohibited new organisms". New Zealand Government. Retrieved January 26, 2012.

- Dietland Müller-Schwarze, Lixing Sun (2003). The Beaver: Natural History of a Wetlands Engineer. Cornell University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-8014-4098-4. Retrieved June 25, 2011.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Riedman, Marianne L. (1982). "The Evolution of Alloparental Care in Mammals and Birds". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 57 (4): 405–435. doi:10.1086/412936.

- Bjorkoyli, Tore; Rosell, Frank (2002). "A Test of the Dear Enemy Phenomenon in the Eurasian Beaver". Animal Behaviour. 63 (6): 1073–78. doi:10.1006/anbe.2002.3010. hdl:11250/2437993.

- Sun, Lixing; Muller-Schwarze, Dietland (1998). "Anal Gland Secretion Codes for Relatedness in the Beaver, Castor Canadensis". Ethology. 104 (11): 917–27. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1998.tb00041.x.

- Rosell, Frank; Nolet, Bart A. (1997). "Factors Affecting Scent-Marking Behavior in Eurasian Beaver (Castor Fiber)" (PDF). Journal of Chemical Ecology. 23 (3): 673–89. doi:10.1023/B:JOEC.0000006403.74674.8a. hdl:11250/2438031.

- Rosell, Frank; Czech, Andrezej (2000). "Response of Foraging Eurasian Beavers Castor Fiber to Predator Odours" (PDF). Wildlife Biology. 6 (1): 13–21. doi:10.2981/wlb.2000.033. hdl:11250/2438045.

- Tom Parfitt (April 11, 2013). "Beaver 'bites man to death'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- Hunt, Katie. "Beavers are gnawing away at the Arctic permafrost, and that's bad for the planet". CNN. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- Rosen, Yereth (May 1, 2020). "Beavers are booming in some parts of the Arctic — and speeding up changes to the tundra". ArcticToday. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- Stewart, William Brenton (1974). Medicine in New Brunswick : a history of the practice of medicine ... from prior to the arrival of the white man in America to the early part of the twentieth century. Moncton: The New Brunswick Medical Society. p. 1.

- Lev E (March 2003). "Traditional healing with animals (zootherapy): medieval to present-day Levantine practice". J Ethnopharmacol. 85 (1): 107–18. doi:10.1016/S0378-8741(02)00377-X. PMID 12576209.

- Badke, David. The Medieval Bestiary: Beaver

- Stephen Pincock (March 28, 2005). "The quest for pain relief: how much have we improved on the past?". Retrieved June 17, 2007.

- Mikkelson, David. "Castoreum Is Produced from Beaver Secretions?". Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- Fenaroli's Handbook Of Flavor Ingredients puts total annual national consumption of castoreum, castoreum extract, and castoreum liquid at about 292 pounds, i.e. per capita consumption of castoreum extract is only .000081 mg/kg/day.

- See Canadian canoe routes (early) and related articles.

- Brown, Jennifer S.H. "Beaver Pelts". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "Park District Kills Beaver in Lincoln Park". MyFoxChicago.com. April 2009. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- Nowak, Ronald M. 1991. pp. 638. Walker's Mammals of the World Fifth Edition, vol. I. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore.

- White, Shelley. "The Beaver As National Symbol: Why Is A Furry Mammal Still An Emblem of Canada?". Huffington Post. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- "AAC template". Beginnings.ioe.ac.uk. Archived from the original on September 26, 2009. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- {{Cite web | url=https://timbeaver100.mit.edu/history-tim |title = History of Tim | Happy 100th Birthday, Tim!} |accessdate=2020-03-10 }

- Kuhnlein, Harriet. "Beaver". Traditional Animal Foods of Indigenous Peoples of Northern North America. McGill University. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- Lydekker 1911.

- Archived September 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Lenten Reader Roundup". Jimmy Akin.Org. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- (in French)Lacoursière, Jacques. Une histoire du Québec ISBN 2-89448-050-4 Explains that Bishop François de Laval in the 17th century posed the question to the theologians of the Sorbonne, who ruled in favour of this decision.

- The Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas II. 147:8 provides legal foundation on which theologians argued in favour of beaver being like fish.

- "In Days Before Easter, Venezuelans Tuck Into Rodent-Related Delicacy". The New York Sun. March 24, 2005. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- Muskrat Love: A Lenten Friday night for some Michiganders

Further reading

- Busher, Peter E (1999). Beaver protection, management, and utilization in Europe and North America. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publ. ISBN 978-0-306-46121-7.

- Coles, Bryony (July–August 2007). "Damming Evidence". Current Archaeology. 18, No.6 (210): 17–25. Article on the history of beavers in Britain.

- Lee Rue, Leonard (2001). Beavers. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-89658-548-5.

North american Beaver.

- Morgan, Lewis Henry (1868). "The American beaver and His Works". J.B. Lippincott & Co.

The American beaver and His Works.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Müller-Schwarze, Dietland; Lixing Sun (2003). The beaver: natural history of a wetlands engineer. Comstock Pub. Associates. ISBN 978-0-8014-4098-4.

- National Parks, January–February (2003). "The Benefits of Beavers". National Parks magazine: 30–35. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The Tent Dwellers – Beavers' habits, habitat and conservation status (as of 1908) are recurring themes by Albert Bigelow Paine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to Castor |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Beaver Facts & Pictures

- Beaver Tracks: How to identify beaver tracks in the wild

- The Romance of the Beaver: Being the History of the Beaver in the Western Hemisphere by A. Radclyffe Dugmore

- Aigas Field Centre Beaver Project – history of a pair of European beavers released into a large enclosure in the Highlands of Scotland.

- The Canadian Encyclopedia, The Beaver

- Video of a beaver building a canal