Soil ecology

Soil ecology is the study of the interactions among soil biology, and between biotic and abiotic aspects of the soil environment.[1] It is particularly concerned with the cycling of nutrients, formation and stabilization of the pore structure, the spread and vitality of pathogens, and the biodiversity of this rich biological community.

Overview

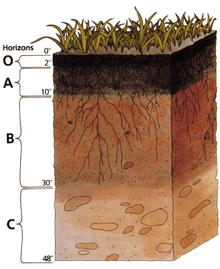

Soil is made up of a multitude of physical, chemical, and biological entities, with many interactions occurring among them. Soil is a variable mixture of broken and weathered minerals and decaying organic matter. Together with the proper amounts of air and water, it supplies, in part, sustenance for plants as well as mechanical support.

The diversity and abundance of soil life exceeds that of any other ecosystem. Plant establishment, competitiveness, and growth is governed largely by the ecology below-ground, so understanding this system is an essential component of plant sciences and terrestrial ecology.

Features of the ecosystem

- Moisture is a major limiting factor on land. Terrestrial organisms are constantly confronted with the problem of dehydration. Transpiration or evaporation of water from plant surfaces is an energy dissipating process unique to the terrestrial environment.

- Temperature variations and extremes are more pronounced in the air than in the water medium.

- On the other hand, the rapid circulation of air throughout the globe results in a ready mixing and remarkably constant content of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

- Although soil offers solid support, air does not. Storing skeletons have been evolved in both land plants and animals and also special means of locomotion have been evolved in the latter.

- Land, unlike the ocean, is not continuous; there are important geographical barriers to free movement.

- The nature of the substrate, although important in water is especially vital in terrestrial environment. Soil, not air, is the source of highly variable nutrients; it is a highly developed ecological subsystem.

Soil food web

An incredible diversity of organisms make up the soil food web. They range in size from the tiniest one-celled bacteria, algae, fungi, and protozoa, to the more complex nematodes and micro-arthropods, to the visible earthworms, insects, small vertebrates, and plants. As these organisms eat, grow, and move through the soil, they make it possible to have clean water, clean air, healthy plants, and moderated water flow.

There are many ways that the soil food web is an integral part of landscape processes. Soil organisms decompose organic compounds, including manure, plant residues, and pesticides, preventing them from entering water and becoming pollutants. They sequester nitrogen and other nutrients that might otherwise enter groundwater, and they fix nitrogen from the atmosphere, making it available to plants. Many organisms enhance soil aggregation and porosity, thus increasing infiltration and reducing surface runoff. Soil organisms prey on crop pests and are food for above-ground animals.

Research

Research interests span many aspects of soil ecology and microbiology, Fundamentally, researchers are interested in understanding the interplay among microorganisms, fauna, and plants, the biogeochemical processes they carry out, and the physical environment in which their activities take place, and applying this knowledge to address environmental problems.

Example research projects are to examine the biogeochemistry and microbial ecology of septic drain field soils used to treat domestic wastewater, the role of anecic earthworms in controlling the movement of water and nitrogen cycle in agricultural soils, and the assessment of soil quality in turf production.[2]

Of particular interest as of 2006 is to understand the roles and functions of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in natural ecosystems. The effect of anthropic soil conditions on arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, and the production of glomalin by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are both of particular interest due to their roles in sequestering atmospheric carbon dioxide.

References

- Access Science: Soil Ecology Archived 2007-03-12 at the Wayback Machine. Url last accessed 2006-04-06

- Laboratory of Soil Ecology and Microbiology. Url last accessed 2006-04-18

Bibliography

- Adl, M.S. (2003). The Ecology of Soil Decomposition. CABI, UK. doi:10.1079/9780851996615.0000. ISBN 978-0851996615.

- Coleman, D.C. & D.A. Crorsley, Jr. (2004). Fundamentals of Soil Ecology (2nd ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0121797263.

- Killham, 1994, Soil Ecology, Cambridge University Press

- Metting, 1993,Soil Microbial Ecology, Marcel Dekker

External links

- "Soil Ecology Society". rutgers.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- Floor, J. Anthoni (2000). "Soil Ecology". Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- "Soil Ecology Section". Ecological Society of America. Retrieved 2016-05-02.

- Yahoo! Soil Ecology Directory. Url last accessed 2006-04-18