Biomechanics

Biomechanics is the study of the structure, function and motion of the mechanical aspects of biological systems, at any level from whole organisms to organs, cells and cell organelles,[1] using the methods of mechanics.[2] Biomechanics is a branch of biophysics.

.jpg)

Etymology

The word "biomechanics" (1899) and the related "biomechanical" (1856) come from the Ancient Greek βίος bios "life" and μηχανική, mēchanikē "mechanics", to refer to the study of the mechanical principles of living organisms, particularly their movement and structure.[3]

Subfields

Biofluid mechanics

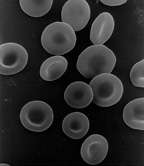

Biological fluid mechanics, or biofluid mechanics, is the study of both gas and liquid fluid flows in or around biological organisms. An often studied liquid biofluid problem is that of blood flow in the human cardiovascular system. Under certain mathematical circumstances, blood flow can be modeled by the Navier–Stokes equations. In vivo whole blood is assumed to be an incompressible Newtonian fluid. However, this assumption fails when considering forward flow within arterioles. At the microscopic scale, the effects of individual red blood cells become significant, and whole blood can no longer be modeled as a continuum. When the diameter of the blood vessel is just slightly larger than the diameter of the red blood cell the Fahraeus–Lindquist effect occurs and there is a decrease in wall shear stress. However, as the diameter of the blood vessel decreases further, the red blood cells have to squeeze through the vessel and often can only pass in a single file. In this case, the inverse Fahraeus–Lindquist effect occurs and the wall shear stress increases.

An example of a gaseous biofluids problem is that of human respiration. Recently, respiratory systems in insects have been studied for bioinspiration for designing improved microfluidic devices.[4]

Biotribology

Biotribology is the study of friction, wear and lubrication of biological systems especially human joints such as hips and knees.[5] In general, these processes are studied in the context of Contact mechanics and tribology.

When two surfaces rub against each other, the effect of that rubbing on either surface will depend on friction, wear and lubrication at the point of contact. For example, the femoral and tibial components of knee implants routinely rub against each other during daily activity such as walking or stair climbing. If the performance of the tibial component needs to be analyzed, the principles of contact mechanics and tribology are used to determine the wear performance of the implant and the lubrication effects of synovial fluid.

Additional aspects of biotribology include analysis of subsurface damage resulting from two surfaces coming in contact during motion, i.e. rubbing against each other, such as in the evaluation of tissue-engineered cartilage.[6]

Comparative biomechanics

Comparative biomechanics is the application of biomechanics to non-human organisms, whether used to gain greater insights into humans (as in physical anthropology) or into the functions, ecology and adaptations of the organisms themselves. Common areas of investigation are Animal locomotion and feeding, as these have strong connections to the organism's fitness and impose high mechanical demands. Animal locomotion, has many manifestations, including running, jumping and flying. Locomotion requires energy to overcome friction, drag, inertia, and gravity, though which factor predominates varies with environment.

Comparative biomechanics overlaps strongly with many other fields, including ecology, neurobiology, developmental biology, ethology, and paleontology, to the extent of commonly publishing papers in the journals of these other fields. Comparative biomechanics is often applied in medicine (with regards to common model organisms such as mice and rats) as well as in biomimetics, which looks to nature for solutions to engineering problems.

Computational biomechanics

Computational biomechanics is the application of engineering computational tools, such as the Finite element method to study the mechanics of biological systems. Computational models and simulations are used to predict the relationship between parameters that are otherwise challenging to test experimentally, or used to design more relevant experiments reducing the time and costs of experiments. Mechanical modeling using finite element analysis has been used to interpret the experimental observation of plant cell growth to understand how they differentiate, for instance.[7] In medicine, over the past decade, the Finite element method has become an established alternative to in vivo surgical assessment. One of the main advantages of computational biomechanics lies in its ability to determine the endo-anatomical response of an anatomy, without being subject to ethical restrictions.[8] This has led FE modeling to the point of becoming ubiquitous in several fields of Biomechanics while several projects have even adopted an open source philosophy (e.g. BioSpine).

Continuum biomechanics

The mechanical analysis of biomaterials and biofluids is usually carried forth with the concepts of continuum mechanics. This assumption breaks down when the length scales of interest approach the order of the micro structural details of the material. One of the most remarkable characteristic of biomaterials is their hierarchical structure. In other words, the mechanical characteristics of these materials rely on physical phenomena occurring in multiple levels, from the molecular all the way up to the tissue and organ levels.

Biomaterials are classified in two groups, hard and soft tissues. Mechanical deformation of hard tissues (like wood, shell and bone) may be analysed with the theory of linear elasticity. On the other hand, soft tissues (like skin, tendon, muscle and cartilage) usually undergo large deformations and thus their analysis rely on the finite strain theory and computer simulations. The interest in continuum biomechanics is spurred by the need for realism in the development of medical simulation.[9]:568

Plant biomechanics

The application of biomechanical principles to plants, plant organs and cells has developed into the subfield of plant biomechanics.[10] Application of biomechanics for plants ranges from studying the resilience of crops to environmental stress[11] to development and morphogenesis at cell and tissue scale, overlapping with mechanobiology.[7]

Sports biomechanics

In sports biomechanics, the laws of mechanics are applied to human movement in order to gain a greater understanding of athletic performance and to reduce sport injuries as well. It focuses on the application of the scientific principles of mechanical physics to understand movements of action of human bodies and sports implements such as cricket bat, hockey stick and javelin etc. Elements of mechanical engineering (e.g., strain gauges), electrical engineering (e.g., digital filtering), computer science (e.g., numerical methods), gait analysis (e.g., force platforms), and clinical neurophysiology (e.g., surface EMG) are common methods used in sports biomechanics.[12]

Biomechanics in sports can be stated as the muscular, joint and skeletal actions of the body during the execution of a given task, skill and/or technique. Proper understanding of biomechanics relating to sports skill has the greatest implications on: sport's performance, rehabilitation and injury prevention, along with sport mastery. As noted by Doctor Michael Yessis, one could say that best athlete is the one that executes his or her skill the best.[13]

Other applied subfields of biomechanics include

- Allometry

- Animal locomotion & Gait analysis

- Biotribology

- Biofluid mechanics

- Cardiovascular biomechanics

- Comparative biomechanics

- Computational biomechanics

- Ergonomy

- Forensic Biomechanics

- Human factors engineering & occupational biomechanics

- Injury biomechanics

- Implant (medicine), Orthotics & Prosthesis

- Kinesiology (kinetics + physiology)

- Musculoskeletal & orthopedic biomechanics

- Rehabilitation

- Soft body dynamics

- Sports biomechanics

History

Antiquity

Aristotle, a student of Plato can be considered the first bio-mechanic, because of his work with animal anatomy. Aristotle wrote the first book on the motion of animals, De Motu Animalium, or On the Movement of Animals.[14] He not only saw animals' bodies as mechanical systems, but pursued questions such as the physiological difference between imagining performing an action and actually doing it.[15] In another work, On the Parts of Animals, he provided an accurate description of how the ureter uses peristalsis to carry urine from the kidneys to the bladder.[9]:2

With the rise of the Roman Empire, technology became more popular than philosophy and the next bio-mechanic arose. Galen (129 AD-210 AD), physician to Marcus Aurelius, wrote his famous work, On the Function of the Parts (about the human body). This would be the world's standard medical book for the next 1,400 years.[16]

Renaissance

The next major biomechanic would not be around until 1452, with the birth of Leonardo da Vinci. Da Vinci was an artist and mechanic and engineer. He contributed to mechanics and military and civil engineering projects. He had a great understanding of science and mechanics and studied anatomy in a mechanics context. He analyzed muscle forces and movements and studied joint functions. These studies could be considered studies in the realm of biomechanics. Leonardo da Vinci studied anatomy in the context of mechanics. He analyzed muscle forces as acting along lines connecting origins and insertions, and studied joint function. Da Vinci tended to mimic some animal features in his machines. For example, he studied the flight of birds to find means by which humans could fly; and because horses were the principal source of mechanical power in that time, he studied their muscular systems to design machines that would better benefit from the forces applied by this animal.[17]

In 1543, Galen's work, On the Function of the Parts was challenged by Andreas Vesalius at the age of 29. Vesalius published his own work called, On the Structure of the Human Body. In this work, Vesalius corrected many errors made by Galen, which would not be globally accepted for many centuries. With the death of Copernicus came a new desire to understand and learn about the world around people and how it works. On his deathbed, he published his work, On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres. This work not only revolutionized science and physics, but also the development of mechanics and later bio-mechanics.[16]

Galileo Galilei, the father of mechanics and part time biomechanic was born 21 years after the death of Copernicus. Galileo spent many years in medical school and often questioned everything his professors taught. He found that the professors could not prove what they taught so he moved onto mathematics where everything had to be proven. Then, at the age of 25, he went to Pisa and taught mathematics. He was a very good lecturer and students would leave their other instructors to hear him speak, so he was forced to resign. He then became a professor at an even more prestigious school in Padua. His spirit and teachings would lead the world once again in the direction of science. Over his years of science, Galileo made a lot of biomechanical aspects known. For example, he discovered that "animals' masses increase disproportionately to their size, and their bones must consequently also disproportionately increase in girth, adapting to loadbearing rather than mere size. The bending strength of a tubular structure such as a bone is increased relative to its weight by making it hollow and increasing its diameter. Marine animals can be larger than terrestrial animals because the water's buoyancy relieves their tissues of weight."[16]

Galileo Galilei was interested in the strength of bones and suggested that bones are hollow because this affords maximum strength with minimum weight. He noted that animals' bone masses increased disproportionately to their size. Consequently, bones must also increase disproportionately in girth rather than mere size. This is because the bending strength of a tubular structure (such as a bone) is much more efficient relative to its weight. Mason suggests that this insight was one of the first grasps of the principles of biological optimization.[17]

In the 17th century, Descartes suggested a philosophic system whereby all living systems, including the human body (but not the soul), are simply machines ruled by the same mechanical laws, an idea that did much to promote and sustain biomechanical study.

Industrial era

The next major bio-mechanic, Giovanni Alfonso Borelli, embraced Descartes' mechanical philosophy and studied walking, running, jumping, the flight of birds, the swimming of fish, and even the piston action of the heart within a mechanical framework. He could determine the position of the human center of gravity, calculate and measure inspired and expired air volumes, and he showed that inspiration is muscle-driven and expiration is due to tissue elasticity.

Borelli was the first to understand that "the levers of the musculature system magnify motion rather than force, so that muscles must produce much larger forces than those resisting the motion".[16] Influenced by the work of Galileo, whom he personally knew, he had an intuitive understanding of static equilibrium in various joints of the human body well before Newton published the laws of motion.[18] His work is often considered the most important in the history of bio-mechanics because he made so many new discoveries that opened the way for the future generations to continue his work and studies.

It was many years after Borelli before the field of bio-mechanics made any major leaps. After that time, more and more scientists took to learning about the human body and its functions. There are not many notable scientists from the 19th or 20th century in bio-mechanics because the field is far too vast now to attribute one thing to one person. However, the field is continuing to grow every year and continues to make advances in discovering more about the human body. Because the field became so popular, many institutions and labs have opened over the last century and people continue doing research. With the Creation of the American Society of Bio-mechanics in 1977, the field continues to grow and make many new discoveries.[16]

In the 19th century Étienne-Jules Marey used cinematography to scientifically investigate locomotion. He opened the field of modern 'motion analysis' by being the first to correlate ground reaction forces with movement. In Germany, the brothers Ernst Heinrich Weber and Wilhelm Eduard Weber hypothesized a great deal about human gait, but it was Christian Wilhelm Braune who significantly advanced the science using recent advances in engineering mechanics. During the same period, the engineering mechanics of materials began to flourish in France and Germany under the demands of the industrial revolution. This led to the rebirth of bone biomechanics when the railroad engineer Karl Culmann and the anatomist Hermann von Meyer compared the stress patterns in a human femur with those in a similarly shaped crane. Inspired by this finding Julius Wolff proposed the famous Wolff's law of bone remodeling.[19]

Applications

The study of biomechanics ranges from the inner workings of a cell to the movement and development of limbs, to the mechanical properties of soft tissue,[6] and bones. Some simple examples of biomechanics research include the investigation of the forces that act on limbs, the aerodynamics of bird and insect flight, the hydrodynamics of swimming in fish, and locomotion in general across all forms of life, from individual cells to whole organisms. With growing understanding of the physiological behavior of living tissues, researchers are able to advance the field of tissue engineering, as well as develop improved treatments for a wide array of pathologies including cancer.[20]

Biomechanics is also applied to studying human musculoskeletal systems. Such research utilizes force platforms to study human ground reaction forces and infrared videography to capture the trajectories of markers attached to the human body to study human 3D motion. Research also applies electromyography to study muscle activation, investigating muscle responses to external forces and perturbations.[21]

Biomechanics is widely used in orthopedic industry to design orthopedic implants for human joints, dental parts, external fixations and other medical purposes. Biotribology is a very important part of it. It is a study of the performance and function of biomaterials used for orthopedic implants. It plays a vital role to improve the design and produce successful biomaterials for medical and clinical purposes. One such example is in tissue engineered cartilage.[6] The dynamic loading of joints considered as impact is dicusssed in detail in.[22]

It is also tied to the field of engineering, because it often uses traditional engineering sciences to analyze biological systems. Some simple applications of Newtonian mechanics and/or materials sciences can supply correct approximations to the mechanics of many biological systems. Applied mechanics, most notably mechanical engineering disciplines such as continuum mechanics, mechanism analysis, structural analysis, kinematics and dynamics play prominent roles in the study of biomechanics.[23]

Usually biological systems are much more complex than man-built systems. Numerical methods are hence applied in almost every biomechanical study. Research is done in an iterative process of hypothesis and verification, including several steps of modeling, computer simulation and experimental measurements.

See also

References

- R. McNeill Alexander (2005) Mechanics of animal movement, Current Biology Volume 15, Issue 16, 23 August 2005, Pages R616-R619. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.08.016

- Hatze, Herbert (1974). "The meaning of the term biomechanics". Journal of Biomechanics. 7 (12): 189–190. doi:10.1016/0021-9290(74)90060-8. PMID 4837555.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, November 2010, s.vv.

- Aboelkassem, Yasser (2013). "Selective pumping in a network: insect-style microscale flow transport". Bioinspiration & Biomimetics. 8 (2): 026004. Bibcode:2013BiBi....8b6004A. doi:10.1088/1748-3182/8/2/026004. PMID 23538838.

- Davim, J. Paulo (2013). Biotribology. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-61705-2.

- Whitney, G. A.; Jayaraman, K.; Dennis, J. E.; Mansour, J. M. (2014). "Scaffold-free cartilage subjected to frictional shear stress demonstrates damage by cracking and surface peeling". J Tissue Eng Regen Med. doi:10.1002/term.1925. PMC 4641823.

- Bidhendi, Amir J; Geitmann, Anja (January 2018). "Finite element modeling of shape changes in plant cells" (PDF). Plant Physiology. 176 (1): 41–56. doi:10.1104/pp.17.01684. PMC 5761827. PMID 29229695.

- Tsouknidas, A., Savvakis, S., Asaniotis, Y., Anagnostidis, K., Lontos, A., Michailidis, N. (2013) The effect of kyphoplasty parameters on the dynamic load transfer within the lumbar spine considering the response of a bio-realistic spine segment. Clinical Biomechanics 28 (9–10), pp. 949–955.

- Fung 1993

- Niklas, Karl J. (1992). Plant Biomechanics: An Engineering Approach to Plant Form and Function (1 ed.). New York, NY: University of Chicago Press. p. 622. ISBN 978-0-226-58631-1.

- Forell, G. V.; Robertson, D.; Lee, S. Y.; Cook, D. D. (2015). "Preventing lodging in bioenergy crops: a biomechanical analysis of maize stalks suggests a new approach". J Exp Bot. 66: 4367–4371. doi:10.1093/jxb/erv108.

- Bartlett, Roger (1997). Introduction to sports biomechanics (1 ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-419-20840-2.

- Michael Yessis (2008). Secrets of Russian Sports Fitness & Training. ISBN 978-0-9817180-2-6.

- Abernethy, Bruce; Vaughan Kippers; Stephanie J. Hanrahan; Marcus G. Pandy; Alison M. McManus; Laurel MacKinnon (2013). Biophysical foundations of human movement (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-4504-3165-1.

- Martin, R. Bruce (23 October 1999). "A genealogy of biomechanics". Presidential Lecture presented at the 23rd Annual Conference of the American Society of Biomechanics University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh PA. Archived from the original on 8 August 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- "American Society of Biomechanics » The Original Biomechanists". www.asbweb.org. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- Mason, Stephen (1962). A History of the Sciences. New York, NY: Collier Books. p. 550.

- Humphrey, Jay D. (2003). The Royal Society (ed.). "Continuum biomechanics of soft biological tissues". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A. 459 (2029): 3–46. Bibcode:2003RSPSA.459....3H. doi:10.1098/rspa.2002.1060.

- R. Bruce Martin (23 October 1999). "A Genealogy of Biomechanics". 23rd Annual Conference of the American Society of Biomechanics. Archived from the original on 17 September 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- Nia, H.T.; et al. (2017). "Solid stress and elastic energy as measures of tumour mechanopathology". Nature Biomedical Engineering. 004: 0004. doi:10.1038/s41551-016-0004. PMC 5621647. PMID 28966873.

- Basmajian, J.V, & DeLuca, C.J. (1985) Muscles Alive: Their Functions Revealed, Fifth edition. Williams & Wilkins.

- Willert, Emanuel (2020). Stoßprobleme in Physik, Technik und Medizin: Grundlagen und Anwendungen (in German). Springer Vieweg.

- Holzapfel, Gerhard A.; Ogden, Ray W. (2009). Biomechanical Modelling at the Molecular, Cellular and Tissue Levels. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 75. ISBN 978-3-211-95875-9.

Further reading

- Cowin, Stephen C., ed. (2008). Bone mechanics handbook (2nd ed.). New York: Informa Healthcare. ISBN 978-0-8493-9117-0.

- Fischer-Cripps, Anthony C. (2007). Introduction to contact mechanics (2nd ed.). New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-68187-0.

- Fung, Y.-C. (1993). Biomechanics: Mechanical Properties of Living Tissues. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-97947-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gurtin, Morton E. (1995). An introduction to continuum mechanics (6 ed.). San Diego: Acad. Press. ISBN 978-0-12-309750-7.

- Humphrey, Jay D. (2002). Cardiovascular solid mechanics : cells, tissues, and organs. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-95168-3.

- Mazumdar, Jagan N. (1993). Biofluids mechanics (Reprint 1998. ed.). Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-02-0927-8.

- Mow, Van C.; Huiskes, Rik, eds. (2005). Basic orthopaedic biomechanics & mechano-biology (3 ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7817-3933-7.

- Peterson, Donald R.; Bronzino, Joseph D., eds. (2008). Biomechanics : principles and applications (2. rev. ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-8534-6.

- Temenoff, J.S.; Mikos, A.G. (2008). Biomaterials : the Intersection of biology and materials science (Internat. ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-009710-1.

- Totten, George E.; Liang, Hong, eds. (2004). Mechanical tribology : materials, characterization, and applications. New York: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 978-0-8247-4873-9.

- Waite, Lee; Fine, Jerry (2007). Applied biofluid mechanics. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-147217-3.

- Young, Donald F.; Bruce R. Munson; Theodore H. Okiishi (2004). A brief introduction to fluid mechanics (3rd ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-45757-2.

External links

| Library resources about Biomechanics |