Glutethimide

Glutethimide is a hypnotic sedative that was introduced by Ciba[2] in 1954 as a safe alternative to barbiturates to treat insomnia. Before long, however, it had become clear that glutethimide was just as likely to cause addiction and caused similar withdrawal symptoms. Doriden was the brand-name version. Current production levels in the United States (the annual quota for manufacturing imposed by the DEA has been three grams, enough for six Doriden tablets, for a number of years) point to it being used only in small scale research. Manufacturing of the drug was discontinued in the US in 1993 and discontinued in several eastern European countries in 2006.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Doriden, Elrodorm, Noxyron, others |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Dependence liability | Medium-high |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Variable (Tmax = 1–6 hours)[1] |

| Protein binding | ~50% |

| Metabolism | Extensive hepatic |

| Elimination half-life | 8–12 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.921 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

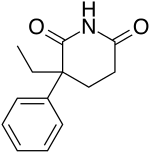

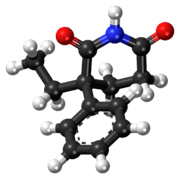

| Formula | C13H15NO2 |

| Molar mass | 217.268 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 84 °C (183 °F) |

| Solubility in water | 999 mg/L (30 °C/86 °F) mg/mL (20 °C) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Long term use

Long-term use rebound effects, which resembled those seen in withdrawal, have anecdotally been described in patients who were still taking a stable dose of the drug. The symptoms included delirium, hallucinosis, convulsions and fever.[3]

Recreational use

Glutethimide is a CYP2D6 enzyme inducer. When taken with codeine, (known on the streets as "hits", "cibas and codeine ", "Dors and 4s") it enables the body to convert higher amounts of the codeine to morphine. The general sedative effect of the glutethimide also adds to the effect of the combination.[4] It produces an intense, long lasting euphoria similar to IV heroin use. Quite a few deaths have occurred from abuse of this combination.[5] The effect was also used clinically, including some research in the 1970s in various countries of using it under carefully monitored circumstances as a form of oral opioid agonist substitution therapy, e.g. as a Substitutionmittel that may be a useful alternative to methadone.[6][7] The demand for this combination in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Newark, NYC, Boston, Baltimore, and surrounding areas of other states and perhaps elsewhere, has led to small-scale clandestine synthesis of glutethimide since 1984,[8]:203 a process that is, like methaqualone (Quaalude) synthesis, somewhat difficult and fraught with potential bad outcomes when amateur chemists manufacture the drugs with industrial-grade precursors without adequate quality control. The fact that the simpler clandestine synthesis of other extinct pharmaceutical depressants like ethchlorvynol, methyprylon, or the oldest barbiturates is not reported would seem to point to a high level of motivation surrounding a unique drug, again much like methaqualone. Production of glutethimide was discontinued in the US in 1993 and in several eastern European countries, most notably Hungary, in 2006. Analysis of confiscated glutethimide seems to invariably show the drug or the results of attempted synthesis, whereas purported methaqualone is in a significant majority of cases found to be inert, or contain diphenhydramine or benzodiazepines.[8]

Legal status

Glutethimide is a Schedule II drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[9] It was originally a Schedule III drug in the United States under the Controlled Substances Act, but in 1991 it was upgraded to Schedule II,[10] several years after it was discovered that misuse combined with codeine increased the effect of the codeine and deaths had resulted from the combination.[11][12] It has a DEA ACSCN of 2550 and a 2013 production quota of 3 g.

Chemistry

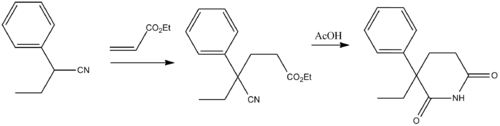

Glutethimide (3-ethyl-3-phenylgutarimide) is synthesized by addition of 2-phenylbutanenitrile to the methylacrylate (Michael reaction), and the subsequent alkaline hydrolysis of the nitrile group in the obtained compound into an amide group, and the subsequent acidic cyclization of the product into the desired glutethimide.[13][14][2][15][16] The (R) isomer has a faster onset and more potent anticonvulsant activity in animal models than the (S) isomer.[17]

References

- Barceloux DG (2012). Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 492–493. ISBN 978-0-471-72760-6.

- US patent 2673205, Hoffmann K, Tagmann E, "3-Disubstituted Dioxopiperidines and the Manufacture thereof", issued 23 March 1954, assigned to CIBA

- Cookson JC (September 1995). "Rebound exacerbation of anxiety during prolonged tranquilizer ingestion". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 88 (9): 544. PMC 1295346. PMID 7562864.

- Shamoian CA (1975). "Codeine and glutethimide. Euphoretic, addicting combination". New York State Journal of Medicine. 75 (1): 97–99. PMID 1053824.

- Havier RG, Lin R (April 1985). "Deaths as a result of a combination of codeine and glutethimide". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 30 (2): 563–6. doi:10.1520/JFS11840J. PMID 3998703. S2CID 45780806.

- Popa D, Loghin F, Imre S, Curea E (August 2003). "The study of codeine-gluthetimide pharmacokinetic interaction in rats". Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 32 (4–5): 867–77. doi:10.1016/s0731-7085(03)00189-4. PMID 12899973.

- Khajawall AM, Sramek JJ, Simpson GM (August 1982). "'Loads' alert". The Western Journal of Medicine. 137 (2): 166–8. PMC 1274052. PMID 7135952.

- Gahlinger P (2003). "Chapter 19. Methaqualone and Glutethimide". Illegal Drugs: A Complete Guide to Their History, Chemistry, Use, and Abuse.

- "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-08-31.

- "Section 1308.12 Schedules of Controlled Substances". Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations. Drug Enforcement Administration.

- Havier RG, Lin R (April 1985). "Deaths as a result of a combination of codeine and glutethimide". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 30 (2): 563–6. doi:10.1520/JFS11840J. PMID 3998703. S2CID 45780806.

- Feuer E, French J (February 1984). "Descriptive epidemiology of mortality in New Jersey due to combinations of codeine and glutethimide". American Journal of Epidemiology. 119 (2): 202–7. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113738. PMID 6695899.

- Tagmann E, Sury E, Hoffmann K (1952). "Über Alkylenimin-Derivate. 2. Mitteilung". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 35 (5): 1541–1548. doi:10.1002/hlca.19520350516.

- DE patent 950193, Hoffmann K Tagmann E, "Verfahren zur Herstellung neuer Dioxopiperidine", issued 4 October 1956, assigned to CIBA

- Salmon-Legagneur F, Neveu C (January 1952). "Sur Les Acides Alpha-Phenyl Alpha-Alcoyl (Ou Phenoalcoyl) Glutariques". Comptes Rendus Hebdomadaires des Seances de L Academie des Sciences. 234 (10): 1060–2.

- Salmon-Legagneur F, Neveu C (1953). "Sur Les Acides Alpha-Phenyl Alpha-Alcoyl (Ou Phenoalcoyl) Glutariques". Bull. Soc. Chim. France. 70.

- Houlihan WJ, Bennett GB (January 1977). "Anti-Anxiety Agents, Anticonvulsants and Sedative-Hypnotics". Annual Reports in Medicinal Chemistry. Academic Press. 12: 10–19. doi:10.1016/S0065-7743(08)61540-7.