Operation Peter Pan

Operation Peter Pan (or Operación Pedro Pan) was a clandestine mass exodus of over 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban minors ages 6 to 18 to the United States over a two-year span from 1960 to 1962. They were sent by their parents who were alarmed by rumors circulating amongst Cuban families that the new government under Fidel Castro was planning to terminate parental rights, and place minors in communist indoctrination centers.

| Part of the Golden exile | |

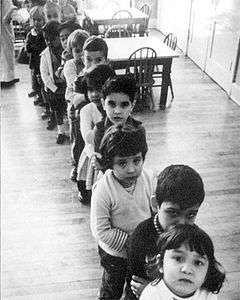

Cuban children waiting in line to emigrate. | |

| Date | 1960–1962 |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Cause | Education in Cuba

|

| Outcome | 14,000 unaccompanied minors arrive in the United States |

Father Bryan O. Walsh of the Catholic Welfare Bureau created the program to provide air transportation to the United States for Cuban children. The operation was the largest mass exodus of minor refugees in the Western Hemisphere at the time.[1] It operated covertly out of fear that it would be viewed as an anti-Castro political enterprise.

Origins

Fears of parents

By 1960 the Cuban government began reforming education strategies. School children were taught military drills, how to bear arms, and anti-American songs.[2] By the spring of 1960, the Cuban government announced the closing of secondary schools and the opening of youth camps where Cuban school children would learn agricultural work. The best students would be sent on scholarships to study in the Soviet Union, while other students in the sixth grade and up would have their school year canceled and go to work in the countryside. By 1961 the Cuban government would seize control of all private schools. Some Cuban parents began to fear the youth camps, closing of private schools, Cuban Literacy Campaign, and sending children to the Soviet Union.[3]

Along with new societal changes, rumors began to swirl around. The CIA-backed Radio Swan station was broadcasting to Cubans that the Cuban government was planning to remove children from their parents and send them to the Soviet Union. Cubans also were worried by the precedents of the Spanish Civil War during which children were evacuated to the Soviet Union.[4]

Program developed

Father Bryan O. Walsh, director of the Catholic Welfare Bureau, developed Operation Peter Pan in November 1960. He was inspired by Pedro Menéndez, a fifteen-year-old Cuban boy who had immigrated to Miami to live with relatives who proved unable to provide for him and sought assistance from the Catholic Welfare Bureau. Walsh understood that many similar youngsters would be immigrating to the United States as Fidel Castro established a Communist government.[5] Speculation that this new government was planning to send minors to the Soviet Union to serve in work camps was causing panic in Cuban families who could not afford to emigrate.[6]

Walsh contacted Tracy Voorhees, a veteran U.S. government official who was serving as the president's Personal Representative for Cuban Refugees, who suggested the Eisenhower Administration could provide funds to support Cuban immigrants once they reached Miami. James Baker, the headmaster of an American school in Havana, met with Walsh and detailed his efforts helping parents expatriate their children to Miami. Before meeting Walsh, Baker's original goal was to establish a boarding school in the United States for Cuban refugee children. However, both later agreed professional social welfare agencies would be better equipped to care for the children.[7] Operation Peter Pan was formed with the understanding that Baker would arrange the children's transportation, and Walsh would arrange for accommodations in Miami. Baker would facilitate the transportation via student visas issued by the American Embassy in Havana.[8] Underground organizations led by the involved parents spread information regarding Operation Peter Pan. Among those who helped alert parents about the program were Penny Powers, Pancho and Bertha Finlay, Drs. Sergio and Serafina Giquel, Sara del Toro de Odio, and Albertina O'Farril. To maintain confidentiality, the program's leaders in the U.S. minimized their communications with their contacts in Cuba.

Operations

Emigration

Between 26 December 1960 and 23 October 1962, many Cuban youths were taken to Miami without their parents.[9][6] Until early 1962, the children were required to have a visa and twenty-five dollars for airfare into the United States.[5] Many family members already in the United States applied for visas and sent the necessary funds to relatives in Cuba. The U.S. Embassy in Havana issued the necessary student visas. When the U.S. Embassy in Havana closed in January 1961, visas were no longer able to be distributed locally. The federal government then granted Walsh permission to issue visa waivers to the Cuban child refugees. Visa waivers were able to be distributed to many children with the help of several Cuban dissidents.[10] On 3 January 1962, the U.S. Department of State announced that Cuban minors no longer needed visas to immigrate to the United States. When Many Cubans believed that Castro's time in power would be short-lived. They anticipated that minors in the United States would eventually rejoin their families in Cuba.[11] Nearly half of the minors who arrived were reunited with family members, while a majority were placed in shelters managed by the Catholic Welfare Bureau.[12]

Funding

By late 1960, Castro had expropriated several companies that made up the American Chamber of Commerce in Havana, including Esso Standard Oil Company and Freeport Sulfur Company. The leaders of these companies moved to Miami while they analyzed the actions of Cuba's new government. Under the impression that Castro's rule would be brief, they agreed to aid the Cuban children by providing funding for Operation Peter Pan. Through collaborations with Baker, these business leaders agreed to help secure donations from multiple US businesses and send them to Cuba. Because Castro was supervising all major monetary transactions, the businessmen were very careful in how the funds were transferred. Some donations were sent to the Catholic Welfare Bureau, and others were written out as checks to citizens living in Miami. These individuals then wrote checks out to the W. Henry Smith Travel Agency in Havana, which helped fund the children's flights to the United States. It was necessary to send the funds in American currency because Castro had ruled that plane tickets could not be purchased with Cuban pesos.[13]

Housing

As the need for shelters grew as the children arrived in increasing numbers, several prominent locations were converted to house them, including Camp Matecumbe, the Opa-locka Airport Marine barracks. Special homes, authorized by state officials and operated by Cuban refugees, were formed in several hundred cities across the nation including Albuquerque, New Mexico; Lincoln, Nebraska; Wilmington, Delaware; Fort Wayne, Indiana; Jacksonville and Orlando, Florida. Many children were placed in foster care in Florida and in other states throughout the United States; some children were placed in positive living environments while others endured emotional and physical neglect. Laws prevented any relocated children from being housed in reform schools or centers for juvenile delinquents. Although a large majority of the minors who arrived in Miami were between the ages of 12 and 18, and more than two-thirds were boys over the age of 12, there were also children as young as 9 years of age. They were predominantly Catholic, but Protestant, Jewish, and non-practicing backgrounds as well. Most were children of the middle or lower classes.[12] The minors were not made available for adoption.

End

Operation Peter Pan ended when all air traffic between the United States and Cuba ceased in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962. Cuban immigrants needed to travel via Spain or Mexico to reach the United States until December 1965 when the United States established a program of Freedom Flights to unite Cuban parents with their children. The Catholic Welfare Bureau reported that once the Freedom Flights began nearly 90% of the minors still in its care were reunited with their parents[12].

The program was unknown outside of Miami until the Cleveland Plain Dealer detailed its size and procedures.[5]

Legacy

Film

In 1962, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy approved funding for a documentary film designed to serve the U.S. government’s campaign against communism. Called The Lost Apple, it recounted the stories of the children who came to Miami.[6]

Pedro Pan children

Many Pedro Pans had trouble assimilating into American society. Many were sent to the United States on the instruction of their parents and felt alienated both from their homeland and the their new home. Some found the United States an unwelcoming place gripped by racial segregation. Those who felt uncomfortable in American society often participated in the growing Civil rights movement and anti-war movement, adopted the traits of the growing youth counterculture, or even rejected the ideology of their parents. Many would desire to outright return to Cuba.[14]

Some Pedro Pan children would involve themselves in the Abdala organization, which was an organization of Cuban-American students dedicated to protesting the Cuban government, and promoting Cuban-American pride. Abdala also maintained an independent position in regards to other in the opposition to the Cuban government.[14]

Some Pedro Pan children would adopt leftist sympathies after becoming involved in social movements in the United States. In 1977 some Pedro Pan emigrants joined the Antonio Maceo Brigade that sympathized with the Cuban government and supported Cuban exiles' travel to Cuba. The brigade would make the first trip of Cuban exiles to Cuba.[14][15]

Controversy over CIA involvement

An ongoing political controversy developed around charges that Operation Peter Pan was not an effort of volunteers and charitable organization, but had been secretly funded by the U.S. government as a covert operation of the Central Intelligence Agency. Author Maria de los Angeles Torres filed a Freedom of Information Act suit to obtain government files on the program. In 1999, a ruling by the U.S. District Court for Northern Illinois determined that this "evacuation of Cuban children turned out not to be a CIA operation at all".[16] The ruling was based in part on the court's review of 733 pages of documentation provided by the CIA for use in an earlier lawsuit.[17]

Participants in Operation Peter Pan

Unaccompanied Cuban minors, known at the time as "Pedro Pans" or "Peter Pans", who participated in the operation include:

- Eduardo Aguirre, United States Ambassador to Spain (2005–2009)[18]

- Frank Angones, first Cuban-born head of the Florida Bar

- Carlos Mayans, former mayor of Wichita, Kansas

- Willy Chirino, Cuban-American musician and salsa singer

- Carlos Eire, author, professor of the history of religion at Yale University

- Felipe de Jesus Estevez, bishop Roman Catholic diocese of St. Augustine (2011–)

- Mario Kenneth Garcia MD, Cosmetic General Dentistry

- Mario Garcia, newspaper designer and media consultant[19]

- Hugo Llorens, United States Ambassador to Honduras (2008 - 2011) and United States Ambassador to Afghanistan (2016-17)[18]

- Raul Andres Martinez Tome, Senior Executive Service, Director of Administration, US Department of Defense (1980-2001)

- Ana Mendieta, artist

- Agustin De Rojas de la Portilla (1944-2011), inventor of the extended-wear contact lens[20]

- Guillermo "Bill" Vidal, former Mayor of Denver (2011) and author of Boxing for Cuba

- Miguel Bezos, Jeff Bezos' (Amazon.com's founder) stepfather, who raised him since he was 4 years old

- U.S. Senator Mel Martinez, former Florida Senator and first Latino chairman of the Republican party

- Lissette Alvarez, singer-songwriter

- Eduardo J. Padrón, current President of Miami Dade College

- Armando Codina, real estate developer[21]

- Alfredo Lanier, journalist for the Chicago Tribune[22]

- Margarita Exquiroz, Miami-Dade County circuit judge and Florida's first female Hispanic judge[23]

- Maria de los Angeles Torres, author of studies of Cuban history[24]

- Carlos Saladrigas, business executive[25][26]

- Nelson Marin, business executive

- Roberto Pérez y Lopez, business executive

- Remberto Perez, business executive Director Cuban American National Foundation

- Martha M. Russ, author Beans and Rice - Growing Up Cuban.

- Luis I Morales, Former Sr. Vice President of Engineering for Glassalum International. Peter Pan arrived in 1961 Miami, Florida Elder with the Presbyterian Church in America.

- Demetrio Perez Jr,educator, politician, radio commentator, entrepreneur and publisher of LIBRE, a bilingual weekly newspaper, and founded the Lincoln-Marti educational group.

- Teresita Fajardo, accountant.

- Avelino Fajardo, postal worker.

- Jorge Enrique Guzman, Engineer.

Ambrose Soler, M.D. pediatric physician, arrived in Miami 1961, lived in Camp Matecumbe, Miami and then an orphanage in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, great grandson of Ambrosio Grillo y Portuondo- hospital in Cuba named after him- physician, mayor, yellow fever vaccine team.

- Mercedes O. Dash, educator, business executive, community activist. Arrived January 25, 1962 placed in foster care in Florida.

- Dave Lombardo, drummer of the heavy metal band Slayer.

- Fr. Enrique J. Sera, Psy.D, pastor Roman Catholic diocese of Orange (CA), Former president of ANSH EE.UU., (National Association of Hispanic Priests)

In culture

Operation Peter Pan is recounted in:

- Waiting for Snow in Havana, in which Carlos Eire describes his experiences during Operation Peter Pan

- Learning to Die in Miami, another memoir by Carlos Eire about his emigration to the United States from Havana

- Operation Pedro Pan: The Untold Exodus of 14,048 Cuban Children, based on the research and interviews of Yvonne M. Conde

- The Red Umbrella, a young-adult historical fiction novel by Christina Diaz Gonzalez, based on her mother's exile from Cuba as a teenager[27]

- Cuba on My Mind: Journeys to a Severed Nation, an exploration of Havana, Miami, and the "one-and-half-generation" by Román de la Campa[28]

- Boxing For Cuba, a 2007 memoir by Bill Vidal, civil servant and mayor of Denver[29]

- Operation Peter Pan, a song written by Tori Amos originally on the B-side to the limited edition release of her single A Sorta Fairytale

- The operation is the main influence behind the Manic Street Preachers song "Baby Elián", the penultimate track from the band's sixth studio album, Know Your Enemy.

- On the 2017 Netflix Original Series One Day at a Time, Lydia Riera, played by Rita Moreno, the grandmother on the show, came to the US via Pedro Pan.[30]

See also

- Cuban migration to Miami

- Cuban American

- Cuban exile

- Mariel boatlift

- Opposition to Fidel Castro

- Operation Baby Lift (South Vietnam, 1975)

- Polita Grau

References

- "Children's Harrowing Journey Depicted in Operation Pedro Pan Exhibit". cubajournal.co. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- "Cuba's 'Peter Pans' Remember Childhood Exodus". National Geographic. 15 August 2015. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "Pedro Pan was born of fear, human instinct to protect children". Miami Herald. 14 May 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- "OPERATION PEDRO PAN'S CODE OF SILENCE". Chicago Tribune. 15 January 1998. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Neyra, Edward (2010). Cuba, Lost and Found. Cincinnati, OH: Clerisy Press. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-1578603909.

- "Pedro Pan". NPR. 3 May 2000. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "Operation Pedro Pan Collections Guide | University of Miami Libraries". sp.library.miami.edu. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Ojito, Mirta (12 January 1998). "Cubans Face Past as Stranded Youths in U.S." The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Krull, Catherine (2014). Cuba in a Global Context. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-8130-4910-6.

- "Operation Pedro Pan Collections Guide | University of Miami Libraries". sp.library.miami.edu. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Kuper, Simon (19 November 2010). "My friend, the Cuban Peter Pan". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "History: The Cuban Children's Exodus". www.pedropan.org. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "Agustin Blazquez". www.cubankids1960.com. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Yvonne M. Conde (2002). Operation Pedro Pan The Untold Exodus of 14,048 Cuban Children. Routledge.

- Vicki L. Ruiz; Virginia Sánchez Korrol. Latinas in the United States, set: A Historical Encyclopedia. Indiana University Press.

- "Torres v. C.I.A.". 12 March 1999. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Torres v. C.I.A.". 15 December 1998. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Moraid, Fernando (2015). The Last Soldiers of the Cold War: The Story of the Cuban Five. Verso. ISBN 978-1781688762. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Muellner, Alexis (29 November 2013). "'Pedro-Pan kid' Mario Garcia had to show resiliency, passion for storytelling early". Tampa Bay Business Journal. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- "Contact lens inventor arrived with Pedro Pan". Miami Herald. 17 February 2011.

- "Effort Begins to List Pedro Pan Children". TheLedger.com. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "CNN - Cuban-Americans struggle with memories of childhood airlifts - January 12, 1998". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- "Fallece Margarita Esquiroz, una de las primeras juezas hispanas de Miami-Dade". El Nuevo Herald (in Spanish). 17 April 2012. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- "Maria de los Angeles Torres | UIC News Center". news.uic.edu. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- Kuper, Simon (19 November 2010). "My friend, the Cuban Peter Pan". Financial Times. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "Interview: Carlos Saladrigas". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Quattlebaum, Mary (4 August 2010). "Christina Diaz Gonzalez's 'The Red Umbrella' and Adam Rex's 'Fat Vampire'". Washington Post. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Flores, Juan. "Latinos, Cubanos and the New Americanism." Foreword to Cuba on My Mind

- "Denver Official Tells Childhood Story of Rescue, Survival". Around the Nation. NPR. 15 July 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "The inspiration behind Netflix's timely 'One Day at a Time' reboot". CNN. 6 January 2016.

Bibliography

- Rita M. Cauce (2012). "Pedro Pan". Tequesta. Historical Association of Southern Florida. 72. ISSN 0363-3705.

External links

- Operation Pedro Pan Group, official site

- "Children of Cuba Remember their Flight to America", NPR

- "Cuban Refugee Children" by Monsignor Bryan O. Walsh

- Pedro Pan Network, hosted by the Miami Herald

- "Cuban Kids in Exile: Pawns of Cold War Politics", Chicago Sun-Times, 24 August 2003, review of Maria de los Angeles Torres' The Lost Apple