Hurricane Jose (2017)

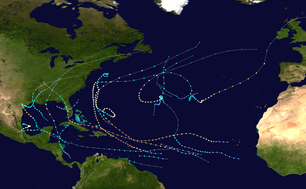

Hurricane Jose was a powerful and erratic tropical cyclone which was the longest-lived Atlantic hurricane since Hurricane Nadine in 2012. Jose was the tenth named storm, fifth hurricane, and third major hurricane of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season. Jose developed into a tropical storm on September 5 from a tropical wave that left the west coast of Africa nearly a week prior. A period of rapid intensification ensued on September 6, when Jose reached hurricane intensity. On September 8, it reached its peak intensity as a high-end Category 4 hurricane. However, due to wind shear, Jose weakened over the next few days as it completed an anti-cyclonic loop north of Hispaniola. Despite weakening to a tropical storm on September 14, Jose managed to regain hurricane intensity the next day as it began to curve northwards. Never strengthening above Category 1 status for the remainder of its lifespan, Jose degraded to a tropical storm once again on September 20. Two days later, Jose transitioned into a post-tropical cyclone as it drifted northeastwards off the coast of New England. By September 26, Jose's remnants dissipated off the East Coast of the United States.

| Category 4 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

Hurricane Jose at peak intensity nearing the Leeward Islands on September 8 | |

| Formed | September 5, 2017 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 25, 2017 |

| (Extratropical after September 22) | |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 155 mph (250 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 938 mbar (hPa); 27.7 inHg |

| Fatalities | 1 total |

| Damage | $2.84 million (2017 USD) |

| Areas affected | Leeward Islands, Bahamas, Bermuda, United States East Coast, Nova Scotia |

| Part of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Initially projected to impact the Antilles already affected by Hurricane Irma, Jose triggered evacuations in catastrophically damaged Barbuda, as well as in Saint Martin. Eventually, as Jose changed its path, its inner core and thus the strongest winds stayed offshore. Nonetheless, Jose still brought tropical storm-force winds to those islands. Later on, Jose brought heavy rain, swells, and rough surf to the East Coast of the United States, causing beach erosion and some flooding. A woman died after she was caught in a rip current in Asbury Park.

Meteorological history

A westward-moving tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa on August 31.[1][2] The wave passed south of Cape Verde on September 2, with a large area of disorganized thunderstorms. However, environmental conditions favored gradual development, which prompted the National Hurricane Center (NHC) to start tracking the system.[3] Early on September 4, a surface low formed within the wave while located around 615 mi (990 km) west-southwest of the Cape Verde islands. Continued organization occurred, and it is estimated a tropical depression formed by 06:00 UTC on September 5, with intensification to tropical storm status occurring six hours later; as such, it was named Jose.[1] Operationally, the NHC did not initiate advisories until 15:00 UTC that day as a tropical storm, nine hours after it had actually formed.[4]

Once Jose became a tropical storm, gradual intensification ensued within the favorable environment of warm sea surface temperatures, low wind shear, and abundant moisture.[5] The storm developed an eye-like feature and symmetric, radial convection as it tracked west-northwest under the influence of a subtropical ridge.[1] Early on September 6, a period of rapid intensification ensued, due to the favorable conditions, with Jose attaining hurricane intensity by 18:00 UTC that day.[1] Meanwhile, Jose, along with hurricanes Irma and Katia, marked the first time that three hurricanes were simultaneously present in the Atlantic since 2010.[6] Despite being close to the outflow from the much larger Hurricane Irma to its west, Jose continued to quickly intensify over the next two days, which eventually culminated with it attaining peak winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 938 mbar (27.7 inHg) at 18:00 UTC on September 8, while located to the east of the Leeward Islands.[1] Upon doing so, Jose, along with Irma nearing landfall in Cuba as a Category 5 hurricane, marked the first time two Atlantic hurricanes had maximum sustained winds of at least 150 mph (240 km/h) occurring simultaneously.[7]

Jose slowly weakened as the eye became cloud-filled and wind shear began affecting the storm,[8] dropping below Category 4 intensity by 18:00 UTC on September 10.[1] The storm weakened below major hurricane status 06:00 UTC the following day, and below Category 2 status by 18:00 UTC September 11 as higher wind shear began to erode the core.[1][9] As the storm was entering an anti-cyclonic loop, Jose was downgraded to a tropical storm at 00:00 UTC on September 15 based on Dvorak estimates which put its wind speed below hurricane strength.[1] At this time the NHC noted that northerly wind shear had kept all significant banding to the southeastern quadrant and the center was to the northwest of most convection.[10] However, as the storm was completing the anti-cyclonic loop later on that day, a reconnaissance plane recorded surface winds above hurricane threshold. Accordingly, the NHC re-upgraded Jose to a hurricane.[11] Rounding the western periphery of the subtropical ridge, Jose moved northward, beginning on September 16.[12] Despite an asymmetric appearance on satellite imagery, the hurricane intensified slightly, reaching a secondary peak intensity of 90 mph (150 km/h) at 12:00 UTC on September 17.[1]

The wind field expanded as Jose continued northward, and a large convective band developed along the northern periphery as the central area of thunderstorms diminished.[13][14] An area of convection and an eye feature reformed on September 19 while the storm was east of North Carolina.[15] A Hurricane Hunters flight on September 20 indicated that Jose weakened to tropical storm status, by which time the storm turned to the northeast.[16] Thereafter, the central convection diminished as the storm passed north of the Gulf Stream over cooler water temperatures.[17] Early on September 22, the NHC redesignated Jose as a post-tropical cyclone, after convection had diminished for over 12 hours, and since the storm had acquired a frontal system.[1] The northern convective band moved over New England while the center drifted southeast of Cape Cod.[18] The remnants of Jose meandered around for another three days, before dissipating on September 25.[1]

Preparations and impact

Leeward Islands and Bahamas

Hurricane Jose threatened the Lesser Antilles within days of catastrophic damage by Hurricane Irma, especially in Barbuda, which was 95% destroyed by Irma.[19] The government of Antigua and Barbuda began efforts on September 8 to evacuate the entire island prior to Jose's anticipated arrival.[20] Nine shelters housing 17,000 persons were opened on Barbuda.[21] Women and children of Saint Martin attempted to flee the island, although men stayed.[22] However, the inner core remained far offshore of the Lesser Antilles,[23] sparing Antigua and Barbuda.[24] Moist southerly flow across the United States Virgin Islands resulted in thunderstorm activity; some flooding occurred on Saint Croix, inflicting $500,000 in damage.[25]

The government of the Bahamas shut down the Nassau International Airport and ordered evacuation from vulnerable Bahamian islands.[26] On September 18 and 19, while passing far to the northwest of Bermuda as a Category 1 hurricane, Jose's outer bands produced wind gusts as high as 46 mph (74 km/h) and nearly 2.5 in (64 mm) of rain on the islands.[27][28]

United States

In advance of the storm, U.S. Geological Survey specialists across three states installed 17 storm-tide sensors – seven in Connecticut, seven in Massachusetts and three in Rhode Island – along shorelines likely to receive some large waves and storm surge from the storm to collect information about the storm's effects.[29] The NHC issued a tropical storm warning for portions of the Atlantic coastline, including the Outer Banks in North Carolina, through Delmarva and the Jersey Shore. Tropical storm warnings were also issued for Long Island, and the coastline of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. Storm surge warnings were also posted for Nantucket, Massachusetts and parts of the Outer Banks.[16]

On September 19, rough surf and swells from Jose flooded portions of the Outer Banks of North Carolina, causing road closures along sections of North Carolina Highway 12.[30] Jose produced a storm surge along the Atlantic coast, with the highest rise recorded at 3.14 ft (0.96 m) in Wachapreague, Virginia.[1] The storm brought heavy winds and rain to Ocean City, Maryland on September 19, with large waves and strong currents flooding a parking lot at the Ocean City Inlet.[31] Sand erosion at Assateague Island National Seashore forced the closure of two parking lots, but had otherwise negligible effects.[32] On September 19, waves from Jose breached a dune and flooded a portion of Delaware Route 1 in Sussex County, Delaware, forcing the road to be closed and traffic detoured.[33] Large waves from Jose caused beach erosion along the Jersey Shore. In North Wildwood, waves from the storm went over a seawall and high tide caused street flooding along the bay.[34] Damage in North Wildwood reached an estimated $2 million.[35] Flooding from Jose shut down Ocean Drive between Avalon and Sea Isle City.[34] One person was found unconscious after being caught in a rip current in Asbury Park; she died in the hospital the following day.[36]

While the storm meandered offshore, tropical storm conditions affected parts of coastal Massachusetts. On Nantucket, wind gusted to 62 mph (100 km/h),[37] and rainfall at the airport reached 6.48 in (165 mm).[38] Rough seas prompted suspensions of ferry service to and from the island.[39] Similar winds affected southern Martha's Vineyard. These conditions downed trees and power lines, disrupting travel and leaving more than 43,000 people without electricity.[37][39] One tree fell on a car in Plymouth,[37] and another struck a home and nearby shed in Norton.[40] Overall damage was relatively light, amounting to $337,000.[41]

See also

References

- Berg, Robbie (February 20, 2018). "Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Jose" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- Eric Blake (August 31, 2017). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- John Cangialosi (September 2, 2017). Tropical Weather Outlook (TXT) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- Chris Landsea (September 4, 2017). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 1 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- Chris Landsea (September 5, 2017). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 2 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- Grinberg, Emanuella (September 7, 2017). "Three hurricanes now in the Atlantic basin". CNN. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- Levenson, Eric (September 9, 2017). "Hurricane Jose strengthens to 'extremely dangerous' Category 4". CNN. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Joan R. Ballard (September 10, 2017). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 22 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Thomas Birchard, David Roth and Chris Sisko (September 12, 2017). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 27 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Eric Blake (September 14, 2017). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 37 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 16, 2017.

- Eric Blake (September 15, 2017). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 42 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- Robbie Berg (September 16, 2017). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 46 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Daniel P. Brown (September 17, 2017). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 51 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Dave Roberts (September 17, 2017). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 52 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Stacy Stewart (September 19, 2017). Hurricane Jose Discussion Number 57 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Lixion Avila (September 20, 2017). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 59 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Lixion Avila (September 20, 2017). Tropical Storm Jose Discussion Number 60 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- David Zelinsky (September 22, 2017). Post-Tropical Cyclone Jose Discussion Number 67 (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Fowler, Tara (September 9, 2017). "Hurricane Jose to Give Irma-Battered Islands Another Lashing". ABC News. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- "Barbuda is trying to totally evacuate today ahead of Hurricane Jose after Hurricane Irma 'demolished' 90% of the island". Business Insider. September 8, 2017.

- Jacguard, Nicholas (September 10, 2017). "Ouragan José : à Saint-Martin, l'angoisse puis le soulagement". Le Parisien. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- Fonsegrieves, Romain (September 9, 2017). "Women and children first in scramble to flee St. Martin". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- Gray, Melissa (September 9, 2017). "Hurricane Jose veers away from Barbuda, sparing island hit by Irma". CNN. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- "L'ouragan José épargne Saint-Martin et Saint-Barthélemy, dévastées par Irma". Les Vix Du Monde. September 9, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- [Virgin Islands Event Report: Flash Flood] (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Vultaggio, Maria (September 8, 2017). "Will Hurricane Jose Hit The Bahamas After Irma?". International Business Times. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- "Jose brings strong winds and risk of thunder". The Royal Gazette. September 18, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- "Weather Summary for September 2017". September 30, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- "More than a dozen USGS Storm-Tide Sensors Deployed for Hurricane Jose". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- Molina, Camila (September 19, 2017). "Rip currents from Hurricane Jose flood areas of OBX; parts of NC 12 closed". The News & Observer. Raleigh, NC. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- Bavaro, Angelo (September 19, 2017). "Ocean City Pounded by Heavy Winds and Rain". Salisbury, MD: WBOC-TV. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- Jeremy Cox (September 26, 2017). "Hurricane Jose's waves shut 2 of 4 Assateague beach parking lots in Va". Delmarva Now. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- Overturf, Madeleine (September 19, 2017). "Waves from Hurricane Jose Breach Dune, Flood Route One". Salisbury, MD: WBOC-TV. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- Pradelli, Chad (September 19, 2017). "Hurricane Jose sends waves crashing over sea wall". Philadelphia, PA: WPVI-TV. Retrieved September 20, 2017.

- Chad Pradelli (September 20, 2017). "Works begins to repair beach erosion at New Jersey shore". WPVI-TV. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- "Woman Dies After Getting Caught in Jose-Spawned Rip Current". U.S. News. Associated Press. September 23, 2017. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- [Massachusetts Event Report: Tropical Storm] (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- David M. Roth (December 5, 2017). "Tropical Storm Jose" (GIF). Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- "Cape, Islands Hit by Power Outages, Storm Damage From Jose". New England Cable News. September 21, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- [Massachusetts Event Report: Tropical Storm] (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- [Hurricane Jose 2017 Massachusetts Event Reports] (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. 2018. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

External links

- The National Hurricane Center's advisory archive on Hurricane Jose

- Track and wind speed history

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Jose (2017). |