Czechoslovak Socialist Republic

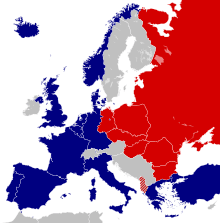

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (Czech and Slovak: Československá socialistická republika, ČSSR) was the name of Czechoslovakia from 1948 to 23 April 1990, when the country was under Communist rule. It has been regarded as a satellite state of the Soviet Union.[1]

Czechoslovak Republic (1948–1960) Československá republika Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (1960–1990) Československá socialistická republika | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948–1990 | |||||||||

Flag

| |||||||||

Motto: Pravda vítězí / Pravda víťazí "Truth prevails" Proletáři všech zemí, spojte se! Proletári všetkých krajín, spojte sa! "Workers of the world, unite!" | |||||||||

Anthem: Kde domov můj (Czech) "Where is my home" Nad Tatrou sa blýska (Slovak) (English: "Lightning Over the Tatras") | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Member of the Warsaw Pact (1955–1989) Satellite state of the Soviet Union | ||||||||

| Capital | Prague | ||||||||

| Common languages | Czech Slovak | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary people's republic (1948–60) Unitary Marxist-Leninist one-party socialist republic (1960–69) Federal Marxist-Leninist one-party socialist republic (1969–89) Federal parliamentary republic (1989–90) | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1948–1953 (first) | Klement Gottwald | ||||||||

• 1989–1990 (last) | Václav Havel | ||||||||

| General Secretary | |||||||||

• 1948–1953 (first) | Klement Gottwald | ||||||||

• 1989 (last) | Karel Urbánek | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1948–1953 (first) | Antonín Zápotocký | ||||||||

• 1989–1990 (last) | Marián Čalfa | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

| 25 February 1948 | |||||||||

| 9 May 1948 | |||||||||

| 11 July 1960 | |||||||||

| 21 August 1968 | |||||||||

| 24 November 1989 | |||||||||

• CSFR established | 23 April 1990 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1985 | 127,900 km2 (49,400 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1985 | 15,498,168 | ||||||||

| Currency | Czechoslovak koruna | ||||||||

| Calling code | 42 | ||||||||

| Internet TLD | .cs | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Formerly: Czechoslovak Republic Československá republika (1948–1960) | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Czechoslovakia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Following the coup d'état of February 1948, when the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia seized power with the support of the Soviet Union, the country was declared a people's republic after the Ninth-of-May Constitution became effective. The traditional name Československá republika (Czechoslovak Republic) was changed on 11 July 1960 following implementation of the 1960 Constitution of Czechoslovakia as a symbol of the "final victory of socialism" in the country, and remained so until the Velvet Revolution in November 1989. Several other state symbols were changed in 1960. Shortly after the Velvet Revolution, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was renamed to the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic.

Name

The official name of the country was the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. Conventional wisdom suggested that it would be known as simply the "Czechoslovak Republic"—its official name from 1920-1938 and from 1945-1960. However, Slovak politicians felt this diminished Slovakia's equal stature, and demanded that the country's name be spelled with a hyphen (i.e. "Czecho-Slovak Republic"), as it was spelled from Czechoslovak independence in 1918 until 1920, and again in 1938 and 1939. President Havel then changed his proposal to "Republic of Czecho-Slovakia"—a proposal that did not sit well with Czech politicians who saw reminders of the 1938 Munich Agreement, in which Nazi Germany annexed a part of that territory. The name also means "Land of the Czechs and Slovaks" while Latinised from the country's original name – "the Czechoslovak Nation"[2] – upon independence in 1918, from the Czech endonym Češi – via its Polish orthography[3]

The name "Czech" derives from the Czech endonym Češi via Polish,[3] from the archaic Czech Čechové, originally the name of the West Slavic tribe whose Přemyslid dynasty subdued its neighbors in Bohemia around AD 900. Its further etymology is disputed. The traditional etymology derives it from an eponymous leader Čech who led the tribe into Bohemia. Modern theories consider it an obscure derivative, e.g. from četa, a medieval military unit.[4] Meanwhile, the name "Slovak" was taken from the Slavic "Slavs" as the origin of the word Slav itself remains uncertain.

During the state's existence, it was simply referred to "Czechoslovakia" or sometimes the "CSSR" and "CSR" in short.

History

Background

| Eastern Bloc | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

|

Allied states

|

|||||||

|

Related organizations |

|||||||

|

Dissent and opposition

|

|||||||

Before the Soviet liberation of Czechoslovakia in 1945, Edvard Beneš, the Czechoslovak leader, agreed to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin's demands for unconditional agreement with Soviet foreign policy and the Beneš decrees.[5] While Beneš was not a Moscow cadre and several domestic reforms of other Eastern Bloc countries were not part of Beneš' plan, Stalin did not object because the plan included property expropriation and he was satisfied with the relative strength of communists in Czechoslovakia compared to other Eastern Bloc countries.[5]

In April 1945, the Third Republic was formed, led by a National Front of six parties. Because of the Communist Party's strength and Beneš's loyalty, unlike in other Central and Eastern European countries, the Kremlin did not require Eastern Bloc politics or "reliable" cadres in Czechoslovak power positions, and the executive and legislative branches retained their traditional structures.[6] The Communists were the big winners in the 1946 elections, taking a total of 114 seats (they ran a separate list in Slovakia). Not only was this the only time a Communist Party won a free election anywhere in Europe during the Cold War era, but it was one of only two free elections ever held in the Soviet bloc, the other one having been held in Hungary a year earlier. Klement Gottwald, leader of the KSČ, became Prime Minister of Czechoslovakia.

However, thereafter, the Soviet Union was disappointed that the government failed to eliminate "bourgeois" influence in the army, expropriate industrialists and large landowners and eliminate parties outside of the "National Front".[7] Hope in Moscow was waning for a Communist victory in the 1948 elections following a May 1947 Kremlin report concluding that "reactionary elements" praising Western democracy had strengthened.[8]

Following Czechoslovakia's brief consideration of taking Marshall Plan funds,[9] and the subsequent scolding of Communist parties by the Cominform at Szklarska Poręba in September 1947, Rudolf Slánský returned to Prague with a plan for the final seizure of power, including the StB's elimination of party enemies and purging of dissidents.[10] Thereafter, Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin arranged a communist coup d'état, followed by the occupation of non-Communist ministers' ministries, while the army was confined to barracks.[11]

On 25 February 1948, Beneš, fearful of civil war and Soviet intervention, capitulated and appointed a Communist-dominated government who was sworn in two days later. Although members of the other National Front parties still nominally figured, this was, for all intents and purposes, the start of out-and-out Communist rule in the country.[12][13][14] Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk, the only prominent Minister still left who wasn't either a Communist or fellow traveler, was found dead two weeks later.[15] On 30 May, a single list of candidates from the National Front—now an organization dominated by the Communist Party—was elected to the National Assembly.

After passage of the Ninth-of-May Constitution on 9 June 1948, the country became a People's Republic until 1960. Although it was not a completely Communist document, it was close enough to the Soviet model that Beneš refused to sign it. He'd resigned a week before it was finally ratified, and died in September. The Ninth-of-May Constitution confirmed that the KSČ possessed absolute power, as other Communist parties had in the Eastern Bloc. On 11 July 1960, the 1960 Constitution of Czechoslovakia was promulgated, changing the name of the country from the "Czechoslovak Republic" to the "Czechoslovak Socialist Republic".

1960-1990

With the exception of the Prague Spring in the late-1960s, Czechoslovakia was characterized by the absence of democracy and competitiveness of its Western European counterparts as part of the Cold War. In 1969, the country became a federative republic comprising the Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic.

Under the federation, social and economic inequities between the Czech and Slovak halves of the country were largely eliminated. A number of ministries, such as Education, were formally transferred to the two republics. However, the centralized political control by the Communist Party severely limited the effects of federalization.

The 1970s saw the rise of the dissident movement in Czechoslovakia, represented (among others) by Václav Havel. The movement sought greater political participation and expression in the face of official disapproval, making itself felt by limits on work activities (up to a ban on any professional employment and refusal of higher education to the dissident's children), police harassment and even prison time.

In late 1989, the country became a democracy again through the Velvet Revolution. In 1992, the Federal Assembly decided it would break up the country into the Czech Republic and Slovakia on 1 January 1993.

Geography

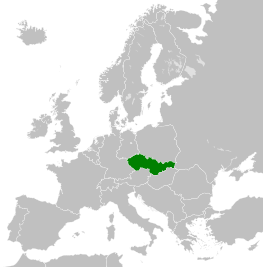

The Czechoslovak Socialist Republic was bounded on the West by West Germany and East Germany, on the North by Poland, on the East by the Soviet Union (via the Ukrainian SSR) and on the South by Hungary and Austria.

Politics

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ) led initially by First Secretary Klement Gottwald, held a monopoly on politics. Following the 1948 Tito-Stalin split and the Berlin Blockade, increased party purges occurred throughout the Eastern Bloc, including a purge of 550,000 party members of the KSČ, 30% of its members.[16][17] Approximately 130,000 people were sent to prisons, labor camps and mines.[17]

The evolution of the resulting harshness of purges in Czechoslovakia, like much of its history after 1948, was a function of the late takeover by the communists, with many of the purges focusing on the sizable numbers of party members with prior memberships in other parties.[18] The purges accompanied various show trials, including those of Rudolf Slánský, Vladimír Clementis, Ladislav Novomeský and Gustáv Husák (Clementis was later executed).[16] Slánský and eleven others were convicted together of being "Trotskyist-zionist-titoist-bourgeois-nationalist traitors" in one series of show trials, after which they were executed and their ashes were mixed with material being used to fill roads on the outskirts of Prague.[16]

Antonín Novotny served as First Secretary of the KSČ from 1953 to 1968. Gustáv Husák was elected first secretary of KSČ in 1969 (changed to General Secretary in 1971) and president of Czechoslovakia in 1975. Other parties and organizations existed but functioned in subordinate roles to KSČ. All political parties, as well as numerous mass organizations, were grouped under the umbrella of National Front of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic. Human rights activists and religious activists were severely repressed.

In terms of political positions, the KSČ maintained the cadre and the nomenklatura lists, with the latter containing every post in each country that was important to the smooth application of party policy, including military posts, administrative positions, directors of local enterprises, social organization administrators, newspapers, etc.[19] The KSČ's nomenklatura lists were thought to contain 100,000 post listings.[19] The names of those that the party considered to be trustworthy enough to secure a nomenklatura post were compiled on the cadre list.[19]

Heads of state and government

- List of presidents of Czechoslovakia

- List of Prime Ministers of Czechoslovakia

Foreign relations

Communist-controlled Czechoslovakia was an active participant in the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon), Warsaw Pact, the UN and its specialized agencies, and Non-Aligned Movement; it was a signatory of conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe.

Administrative divisions

| Part of a series on the |

| Czechoslovak Socialist Republic |

|---|

|

|

History |

- 1960–1992: 10 regions (kraje), Prague, and (since 1970) Bratislava; divided in 109–114 districts (okresy); the kraje were abolished temporarily in Slovakia in 1969–1970 and for many functions since 1991 in Czechoslovakia; in addition, the two internal republics, the Czech Socialist Republic and Slovak Socialist Republic, were established in 1969.

Economy

The Czechoslovak economy was a centrally planned command economy with links controlled by the communist party, similar to the Soviet Union. It had a large metallurgical industry, but was dependent on imports for iron and nonferrous ores. Like the rest of the Eastern Bloc, producer goods were favored over consumer goods, causing consumer goods to be lacking in quantity and quality. This resulted in a shortage economy.[20][21] Economic growth rates lagged well behind Czechoslovakia's western European counterparts.[22] Investments made in industry did not yield the results expected, and consumption of energy and raw materials was excessive. Czechoslovak leaders themselves decried the economy's failure to modernize with sufficient speed.

- Industry: Extractive and manufacturing industries dominated sector. Major branches included machinery, chemicals, food processing, metallurgy, and textiles. Industry was wasteful of energy, materials, and labor and slow to upgrade technology, but was a source of high-quality machinery and arms for other communist countries.

- Agriculture: Minor sector but supplied bulk of food needs. Dependent on large imports of grains (mainly for livestock feed) in years of adverse weather. Meat production constrained by shortage of feed, but high per capita consumption of meat.

- Foreign Trade: Exports estimated at US$17.8 billion in 1985, of which 55% was machinery, 14% fuels and materials, and 16% manufactured consumer goods. Imports at estimated US$17.9 billion in 1985, of which 41% was fuels and materials, 33% machinery, and 12% agricultural and forestry products. In 1986, about 80% of foreign trade was with communist countries.

- Exchange Rate: Official, or commercial, rate Kcs 5.4 per US$1 in 1987; tourist, or noncommercial, rate Kcs 10.5 per US$1. Neither rate reflected purchasing power. The exchange rate on the black market was around Kcs 30 per US$1, and this rate became the official one once the currency became convertible in the early 1990s.

- Fiscal Year: Calendar year.

- Fiscal Policy: State almost exclusive owner of means of production. Revenues from state enterprises primary source of revenues followed by turnover tax. Large budget expenditures on social programs, subsidies, and investments. Budget usually balanced or small surplus.

Resource base

After World War II, the country was short on energy, relying on imported crude oil and natural gas from the Soviet Union, domestic brown coal, and nuclear and hydroelectric energy. Energy constraints were a major factor in 1980s.

Demographics

Society and social groups

Homosexuality was decriminalized in 1962.[23]

Emigration

Historically, emigration has always been an option for Czechs and Slovaks dissatisfied with the situation at home. Each wave of emigration had its own impetus. In the 19th century, the reasons were primarily economic. In the 20th century, emigration was largely prompted by political turmoil, though economic factors still played a role. The first major wave of emigration in the 20th century came after the communists came to power, and the next wave began after the Prague Spring was suppressed.

In the 1980s, the most popular way to emigrate to the West was to travel to Yugoslavia by automobile and, once there, take a detour to Greece, Austria, or Italy (Yugoslav border restrictions were not as strict as those of the Warsaw Pact nations). Only a small percentage of those who applied to emigrate legally could do so. The exact details of the process have never been published, but a reasonably clear picture can be gleaned from those who succeeded. It was a lengthy and costly process. Those applicants allowed to even consider emigration were required to repay the state for their education, depending on their level of education and salary, at a rate ranging from 4,000 Kčs to 10,000 Kčs. (The average yearly wage was about Kčs33,600 in 1984.) The applicant was likely to lose his job and be socially ostracized.

Technically, at least, such emigres would be allowed to return for visits. Those who had been politically active, such as Charter 77 signatories, found it somewhat easier to emigrate, but they were not allowed to return and reportedly had to pay the state exorbitant fees—Kčs23,000 to as much as Kčs80,000—if they had graduated from a university. Old-age pensioners had no problem visiting or emigrating to the West. The reasons for this were purely economic; if they decided to stay in the West, the state no longer had to pay their pension.

There is (and always was) a huge discrepancy between "official statistics" (i.e. numbers issued by the communist regime) on how many people emigrated from Czechoslovakia and "illegal refugee" statistics published by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). This discrepancy was not specific to Czechoslovakia only; a similar situation applied for all Eastern Bloc countries, as their authoritarian regimes preferred to downplay and suppress real numbers.

Official statistics for the early 1980s show that, on the average, 3,500 people emigrated legally each year. From 1965 to 1983, a total of 33,000 people emigrated legally. This figure undoubtedly included a large number of ethnic Germans resettled in East Germany. The largest émigré communities are located in Austria, West Germany, the United States, Canada, and Australia.

Unofficial figures are much larger. It is estimated that between 1948 and 1989 close to 1 million people left communist-ruled Czechoslovakia. The largest exoduses occurred following the communist takeover in February 1948 and following the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, with around 200,000 people leaving in each wave. A very similar 200,000-strong refugee wave left Hungary in 1956 after their failed anti-communist revolution. In the 1950s, when the regime was at its harshest and the "Iron Curtain" was close to impenetrable, emigration was very low. It increased between 1969 and 1989, when close to 40,000 people were leaving the country each year. All of them were sentenced to imprisonment in absentia by the communist regime for leaving the country illegally.

Religion

Religion was oppressed and attacked in communist-era Czechoslovakia.[24] In 1991, 46.4% were Roman Catholics, Atheists made up 29.5%, 5.3% were Evangelical Lutherans, and 16.7% were n/a, but there were huge differences between the 2 constituent republics – see Czech Republic and Slovakia.

Culture and society

Health, social welfare and housing

After World War II, free health care was available to all citizens. National health planning emphasized preventive medicine; factory and local health-care centers supplemented hospitals and other inpatient institutions. Substantial improvement in rural health care in 1960s and 1970s.

Mass media

The mass media in Czechoslovakia was controlled by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). Private ownership of any publication or agency of the mass media was generally forbidden, although churches and other organizations published small periodicals and newspapers. Even with this informational monopoly in the hands of organizations under KSČ control, all publications were reviewed by the government's Office for Press and Information.

Military

See also

Notes

- Rao, B. V. (2006), History of Modern Europe Ad 1789–2002: A.D. 1789–2002, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Masaryk, Tomáš. Czechoslovak Declaration of Independence. 1918.

- Czech. CollinsDictionary.com. Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Online Etymology Dictionary. "Czech". Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Wettig 2008, p. 45

- Wettig 2008, p. 86

- Wettig 2008, p. 152

- Wettig 2008, p. 110

- Wettig 2008, p. 138

- Grogin 2001, p. 134

- Grenville 2005, p. 371

- Grenville 2005, pp. 370–371

- Grogin 2001, pp. 134–135

- Saxonberg 2001, p. 15

- Grogin 2001, p. 135

- Crampton 1997, p. 262

- Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 477

- Crampton 1997, p. 270

- Crampton 1997, p. 249

- Dale 2005, p. 85

- Bideleux & Jeffries 2007, p. 474

- Hardt & Kaufman 1995, p. 17

- http://www.radio.cz/fr/rubrique/histoire/vers-la-decriminalisation-de-lhomosexualite-sous-le-communisme

- Catholics in Communist Czechoslovakia: A Story of Persecution and Perseverance

References

- Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian (2007), A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-36626-7

- Black, Cyril E.; English, Robert D.; Helmreich, Jonathan E.; McAdams, James A. (2000), Rebirth: A Political History of Europe since World War II, Westview Press, ISBN 0-8133-3664-3

- Crampton, R. J. (1997), Eastern Europe in the twentieth century and after, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-16422-2

- Dale, Gareth (2005), Popular Protest in East Germany, 1945–1989: Judgements on the Street, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7146-5408-9

- Frucht, Richard C. (2003), Encyclopedia of Eastern Europe: From the Congress of Vienna to the Fall of Communism, Taylor & Francis Group, ISBN 0-203-80109-1

- Grenville, John Ashley Soames (2005), A History of the World from the 20th to the 21st Century, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-28954-8

- Grenville, John Ashley Soames; Wasserstein, Bernard (2001), The Major International Treaties of the Twentieth Century: A History and Guide with Texts, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-23798-X

- Grogin, Robert C. (2001), Natural Enemies: The United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War, 1917–1991, Lexington Books, ISBN 0-7391-0160-9

- Hardt, John Pearce; Kaufman, Richard F. (1995), East-Central European Economies in Transition, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-612-0

- Saxonberg, Steven (2001), The Fall: A Comparative Study of the End of Communism in Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary and Poland, Routledge, ISBN 90-5823-097-X

- Wettig, Gerhard (2008), Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-5542-9

External links

- RFE/RL Czechoslovak Unit, Open Society Archives, Budapest.