Caribbean Spanish

Caribbean Spanish (Spanish: español caribeño) is the general name of the Spanish dialects spoken in the Caribbean region. It resembles the Spanish spoken in the Canary Islands and more distantly the one spoken in western Andalusia.

| Spanish language |

|---|

Spanish around the 13th century |

| Overview |

| History |

|

| Grammar |

| Dialects |

| Dialectology |

| Interlanguages |

| Teaching |

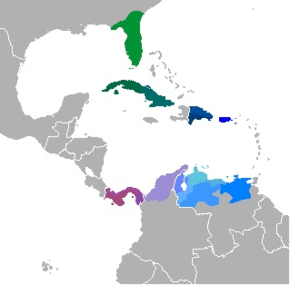

More precisely, the term refers to the Spanish language as spoken in the Caribbean islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic as well as in Panama, Venezuela, and the Caribbean coast of Colombia.

Varieties of Caribbean Spanish, including Florida, The Greater Antilles, Panama and the Atlantic coast of Colombia and Venezuela.

Phonology

- Seseo, where /θ/ and /s/ merge to /s/, as in the rest of the Americas, in the Canary Islands and in southern Spain.

- Yeísmo, where /ʎ/ and /ʝ/ merge to /ʝ/, as in many other Spanish dialects.

- /s/ is debuccalized to [h] at the end of syllables, as is common in the southern half of Spain, the Canaries and much of Spanish America: los amigos [lo(h‿)aˈmiɣo(h)] ('the friends'), dos [ˈdo(h)] ('two').[1]

- Syllable-initial /s/ is also sporadically debuccalized, although this process is documented only in certain areas, such as parts of Puerto Rico: cinco centavos [ˈsiŋkohenˈtaβo], la semana pasada [laheˈmanapaˈsaða].

- /x/ pronounced [h], as is common in Andalusia, the Canary islands and various parts of South America.

- lenition of /tʃ/ to [ʃ] mucho [ˈmut͡ʃo]→[ˈmuʃo], as in part of Andalusia or in Chile.

- Word-final /n/ is realized as a velar nasal [ŋ] (velarization). It can be elided, with backwards nasalization of the preceding vowel: [pan]→[pã]; as in part of Andalusia.

- Deletion of intervocalic /ð/ and word final /d/, as in many Spanish dialects: cansado [kãnˈsao] ('tired'), nada [ˈnaða]→[ˈna] ('nothing'), and perdido [perˈði.o] ('lost'), mitad [miˈtad]→[miˈta]

- Syllable final 'r' has a variety of realisations:

- lambdacism /ɾ/→/l/ porque [poɾke]→ [polke]

- deletion of /ɾ/ hablar [aˈβlaɾ]→[aˈβla]

- assimilation to following consonant, causing gemination. carne [ˈkaɾne]→[ˈkanːe], [ˈveɾðe]→[ˈvedːe]. Most notable of Spanish spoken in and around Havana.

- /ɹ/ is a common realization in middle and upper classes in Puerto Rico under the influence of English.

- vocalization of /ɾ/ to /j/ hacer [aˈseɾ]→[aˈsej] in the Cibao region of the Dominican Republic.

- aspiration /ɾ/→/h/ carne [ˈkaɾne]→[ˈkahne]

- /r/ is devoiced to /r̥/ in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico: cotorra [koˈtora]→[koˈtor̥a] and realised as a uvular fricative /ʀ/, /χ/ (uvularization) in rural Puerto Rican dialects

- Several neutralizations also occur in the syllable coda. The liquids /l/ and /ɾ/ may neutralize to [j] (Cibaeño Dominican celda/cerda [ˈsejða] 'cell'/'bristle'), [l] (alma/arma [ˈalma] 'soul'/'weapon', comer [koˈme(l)] 'to eat'), or as complete regressive assimilation (pulga/purga [ˈpuɡːa] 'flea'/'purge').[2] The deletions and neutralizations (/ɾ/→/l/→/j/→∅) show variability in their occurrence, even with the same speaker in the same utterance, which implies that nondeleted forms exist in the underlying structure.[3] That is not to say that these dialects are on the path to eliminating coda consonants since such processes have existed for more than four centuries in these dialects.[4] Guitart (1997) argues that it is the result of speakers acquiring multiple phonological systems with uneven control, like that of second language learners.

- In Spanish there are geminated consonants in Caribbean Spanish when /l/ and /ɾ/ in syllabic coda are assimilated to the following consonant.[5] Examples of Cuban Spanish:

| /l/ or /r/ + /f/ | > | /d/ + /f/: | [ff] | a[ff]iler, hue[ff]ano | (Sp. ‘alfiler’, ‘huérfano’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /s/ | > | /d/ + /s/: | [ds] | fa[ds]a), du[ds]e | (Sp. ‘falsa or farsa’, ‘dulce’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /h/ | > | /d/ + /h/: | [ɦh] | ana[ɦh]ésico, vi[ɦh]en | (Sp. ‘analgésico’, ‘virgen’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /b/ | > | /d/ + /b/: | [b˺b] | si[b˺b]a, cu[b˺b]a | (Sp. ‘silba or sirva’, ‘curva’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /d/ | > | /d/ + /d/: | [d˺d] | ce[d˺d]a, acue[d˺d]o | (Sp. ‘celda or cerda’, ‘acuerdo’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /g/ | > | /d/ + /g/: | [g˺g] | pu[g˺g]a, la[g˺g]a | (Sp. ‘pulga or purga’, ‘larga’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /p/ | > | /d/ + /p/: | [b˺p] | cu[b˺p]a, cue[b˺p]o | (Sp. ‘culpa’, ‘cuerpo’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /t/ | > | /d/ + /t/: | [d˺t] | sue[d˺t]e, co[d˺t]a | (Sp. ‘suelte o suerte’, ‘corta’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /ʧ/ | > | /d/ + /ʧ/: | [d˺ʧ] | co[d˺ʧ]a, ma[d˺ʧ]arse | (Sp. ‘colcha o corcha’, ‘marcharse’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /k/ | > | /d/ + /k/: | [g˺k] | vo[g˺k]ar, ba[g˺k]o | (Sp. ‘volcar’, ‘barco’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /m/ | > | /d/ + /m/: | [mm] | ca[mm]a, a[mm]a | (Sp. ‘calma’, ‘alma o arma’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /n/ | > | /d/ + /n/: | [nn] | pie[nn]a, ba[nn]eario | (Sp. ‘pierna’, ‘balneario’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /l/ | > | /d/ + /l/: | [ll] | bu[ll]a, cha[ll]a | (Sp. ‘burla’, ‘charla’) |

| /l/ or /r/ + /r/ | > | /d/ + /r/: | [r] | a[r]ededor | (Sp. ‘alrededor’) |

| _____________ | _____ | __________ | _________ | ______________________ | ___________________________ |

Morphology

- As in all American variants of Spanish the third person plural pronoun ustedes has supplanted the pronoun vosotros/vosotras.

- Voseo is now completely absent from insular Caribbean Spanish. Contemporary commentators such as the Cuban Esteban Pichardo speak of its survival as late as the 1830s (see López Morales 1970:136‑142) but by the 1870s it appears to have become confined to a small number of speakers from the lowest social strata. In the north west of Venezuela, in the states of Falcon and Zulia, in the north of the Cesar department, in the south of La Guajira department on Colombia's Atlantic coast and the Azurero Peninsula in Panama voseo is still used.

- The diminutive (ito, ita) takes the form (ico, ica) after /t/: pato→patico, pregunta→preguntica. BUT perro→perrito.

- Possibly as a result of the routine elision of word-final [s], some speakers may use [se] as a plural marker, but generally this tendency is limited to words with singular forms that end in a stressed vowel: [kaˈfe] café ‘coffee’ → [kaˈfese] ‘coffees’, [soˈfa] sofá ‘sofa’ → [soˈfase] ‘sofas’.

Syntax

Vocabulary

- The second-person subject pronouns, tú (or vos in Central America) and usted, are used more frequently than in other varieties of Spanish, contrary to the general Spanish tendency to omit them when meaning is clear from the context (see Pro-drop language). Thus, tú estás hablando instead of estás hablando. The tendency is strongest in the island countries and, on the mainland, in Nicaragua, where voseo (rather than the use of tú for the second person singular familiar) is predominant.

- So-called "wh-questions", which in standard Spanish are marked by subject/verb inversion, often appear without the inversion in Caribbean Spanish: "¿Qué tú quieres?" for standard "¿Qué quieres (tú)?" ("What do you want?").[6][7]

gollark: Don't think so, I mostly use FOSS tools anyway.

gollark: Fine, I'll reschedule that to Wednesday.

gollark: Although maybe stuff has occurred with that, who knows.

gollark: I doubt they'd be judged substantially on ridiculous twitter drama.

gollark: I doubt the tweet would do anything though.

See also

References

- Guitart (1997:515, 517)

- Guitart (1997:515)

- Guitart (1997:515, 517–518)

- Guitart (1997:518, 527), citing Boyd-Bowman (1975) and Labov (1994:595)

- Arias, Álvaro (2019). "Fonética y fonología de las consonantes geminadas en el español de Cuba". Moenia. 25, 465-497

- Lipski (1994:61)

- Gutiérrez-Bravo (2008:225)

Bibliography

- Arias, Álvaro (2019). "Fonética y fonología de las consonantes geminadas en el español de Cuba". Moenia. 25, 465-497.

- Boyd-Bowman, Peter (1975), "A sample of Sixteenth Century 'Caribbean' Spanish Phonology.", in Milán, William G.; Staczek, John J.; Zamora, Juan C. (eds.), 1974 Colloquium on Spanish and Portuguese Linguistics, Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, pp. 1–11

- Guitart, Jorge M. (1997), "Variability, multilectalism, and the organization of phonology in Caribbean Spanish dialects", in Martínez-Gil, Fernando; Morales-Front, Alfonso (eds.), Issues in the Phonology and Morphology of the Major Iberian Languages, Georgetown University Press, pp. 515–536

- Gutiérrez-Bravo, Rodrigo (2008), "Topicalization and Preverbal Subjects in Spanish wh-interrogatives", in Bruhn de Garavito, Joyce; Valenzuela, Elena (eds.), Selected Proceedings of the 10th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium, Somerville, MA: Cascadilla, pp. 225–236

- Labov, William (1994), Principles of Linguistic Change: Volume I: Internal Factors, Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers

- Lipski, John (1977), "Preposed Subjects in Questions: Some Considerations", Hispania, 60: 61–67, doi:10.2307/340393, JSTOR 340393

- On the Non-Creole Basis for Afro-Caribbean Spanish John M. Lipski

Further reading

- Cedergren, Henrietta (1973), The Interplay of Social and. Linguistic Factors in Panama, Cornell University

- Poplack, Shana (1979), Function and process in a variable phonology, University of Pennsylvania

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.