Socialism in Tunisia

Socialism in Tunisia or Tunisian socialism is a political philosophy that is shared by various political parties of the country. It has played a role in the country's history from the time of the Tunisian independence movement against France up through the Tunisian Revolution to the present day.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Tunisia |

|

|

|

Judiciary |

|

Administrative divisions |

|

|

|

|

Tunisian Communist Party

Neo Destour

Movement of Socialist Democrats

In 1978, the Movement of Socialist Democrats (MDS) was founded by defectors from the then ruling Socialist Destourian Party (PSD) and liberal-minded expatriates. The founders of the MDS had already been involved in the establishment of the Tunisian Human Rights League (LTDH) in 1976/77.[1] Its first secretary general was Ahmed Mestiri who had been a member of the PSD and interior minister in the government of Habib Bourguiba, but was dropped from the government in 1971 and expelled from the party after he had called for democratic reforms and pluralism. The MDS to officially register in 1983. It was one of three legal oppositional parties during the 1980s. The MDS welcomed Zine El Abidine Ben Ali taking over the presidency from the logterm head of state Bourguiba in 1987. Many MDS members believed that Ben Ali really pursued reforms and liberalisation and defected to his Constitutional Democratic Rally (RCD), weakening the MDS. Ahmed Mestiri led the party until 1990. In the early 1990s, the party was torn between cooperation with the government and opposition.[2] Those who strove for a strictly oppositional course left the party or were edged out.[3] In 1994, a group of MDS dissidents around Mustapha Ben Jaafar founded the Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties (FDTL), which was only legalised in 2002.

Unionist Democratic Union

Popular Unity Party

Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties

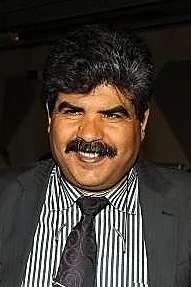

In 9 April 1994, the Democratic Forum for Labour and Liberties (Ettakatol or FDTL) was founded and officially recognized on 25 October 2002. Is a social democratic and secularist political party in Tunisia.[4][5] Its founder and Secretary-General is the radiologist Mustapha Ben Jafar.[6]

Ettajdid Movement

Active from 1993 to 2012, the Ettajdid Movement (Movement for Renewal) was a centre-left secularist, democratic socialist and social liberal political party in Tunisia.[7][8][8][9][10][11] It was led by Ahmed Ibrahim.[12] For the Constituent assembly election, Ettajdid formed a strongly secularist alliance called Democratic Modernist Pole (PDM), of which it was the mainstay.[13][14]

Ahmed Brahim was the First Secretary of the movement and also the leader of the Democratic Modernist Pole until April 2012, when his party merged into the Social Democratic Path of which he became the president. He was the Ettajdid Movement's candidate for President of Tunisia in the 2009 presidential election.[15][16] Brahim was in favor of the emergence of a "democratic modern and secular [laicist] state" not connected with Islamists. According to Brahim, this would require "radical" reform of the electoral system, which would improve the political climate in guaranteeing freedom of assembly and a large scale independent press, as well as repealing a law that regulated public discourse of electoral candidates.[17]

Congress for the Republic

Socialist Party

Tunisian Revolution

.jpg)

The Tunisian Revolution[18] was an intensive campaign of civil resistance, including a series of street demonstrations taking place in Tunisia, and led to the ousting of longtime president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in January 2011. It eventually led to a thorough democratization of the country and to free and democratic elections with the Tunisian Constitution of 2014,[19] which is seen as progressive, increases human rights, gender equality, government duties toward people, lays the ground for a new parliamentary system and makes Tunisia a decentralized and open government.[19][20] And with the held of the country first parliamentary elections since the 2011 Arab Spring[21] and its presidentials on 23 November 2014,[22] which finished its transition to a democratic state. These elections were characterized by the fall in popularity of Ennahdha, for the secular Nidaa Tounes party, which became the first party of the country.[23]

The demonstrations were caused by high unemployment, food inflation, corruption,[24][25] a lack of political freedoms like freedom of speech[26] and poor living conditions. The protests constituted the most dramatic wave of social and political unrest in Tunisia in three decades[27][28] and resulted in scores of deaths and injuries, most of which were the result of action by police and security forces against demonstrators. The protests were sparked by the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi on 17 December 2010[29][30][31] and led to the ousting of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali 28 days later on 14 January 2011, when he officially resigned after fleeing to Saudi Arabia, ending 23 years in power.[32][33] Labour unions were said to be an integral part of the protests.[34] The Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet was awarded the 2015 Nobel Peace Prize for "its decisive contribution to the building of a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia in the wake of the Tunisian Revolution of 2011".[35] The protests inspired similar actions throughout the Arab world.

People's Movement

Founded in 2011, the People's Movement is a secularist and Arab nationalist political party in Tunisia.[36] It has a social democratic platform and is aligned with workers groups.[37] The party belongs to the Popular Front coalition of left-leaning parties led by Hamma Hammami, leader of the Tunisian Workers Party.[38] The coalition includes ten nationalist left-wing groups, including the People's Movement.[39]

Democratic Modernist Pole

Democratic Current

Social Democratic Path

Popular Front

The Popular Front for the Realization of the Objectives of the Revolution, short Popular Front (ej-Jabha), is a leftist political and electoral alliance in Tunisia, made up of nine political parties and numerous independents. The coalition was formed in October 2012, bringing together 12 mainly left-wing Tunisian parties including the Democratic Patriots' Unified Party, the Workers' Party, Green Tunisia, the Movement of Socialist Democrats (which has left), the Tunisian Ba'ath Movement and Arab Democratic Vanguard Party, two different parties of the Iraqi branch of Ba'ath Party, and other progressive parties.[40] The number of parties involved in the coalition has since decreased to nine.[41] Approximately 15,000 people attended the coalition's first meeting in Tunis.[42]

The coordinator of the Popular Front coalition, Chokri Belaid, was killed by an unknown gunman on 6 February 2013. An estimated 1,400,000 people took part in his funeral,[43] while protesters clashed with police and Ennahda supporters,[44]

On 25 July 2013, Mohamed Brahmi, founder a former leader of the Popular Front, assassinated on [45] was assassinated. Numerous protests erupted in the streets following his assassination. Following his death, hundreds of his supporters, including relatives and party members of the People's Movement, demonstrated in front of the Interior Ministry's building on Avenue Habib Bourguiba and blamed the incumbent Ennahda Party and their followers for the assassination.[46][47] Hundreds of supporters also protested in Brahmi's hometown of Sidi Bouzid.[46]

References

- Alexander, Christopher (2010), Tunisia: Stability and Reform in the Modern Maghreb, Routledge, p. 46

- Waltz, Susan E. (1995), Human Rights and Reform: Changing the Face of North African Politics, University of California Press, p. 70

- Waltz (1995), Human Rights and Reform, p. 185

- "Factbox – How Tunisia's election will work", Reuters, 22 October 2011, retrieved 22 October 2011

- "Tunisia - Opposition Parties". Global Security. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- "Photo of Mustapha Ben Jaafar, 22 Jan 2011". Getty Images. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- Marks, Monica (26 October 2011), "Can Islamism and Feminism Mix?", New York Times, retrieved 28 October 2011

- Fisher, Max (27 October 2011), "Tunisian Election Results Guide: The Fate of a Revolution", The Atlantic, retrieved 28 October 2011

- Ryan, Yasmine (14 January 2011). "Tunisia president not to run again". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- Chebbi, Najib (18 January 2011). "Tunisia: who are the opposition leaders?". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- "Tunisia seeks to form unity cabinet after Ben Ali fall". BBC News. 16 January 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- "Tunisia forms national unity government amid unrest". BBC. 17 January 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- Chrisafis, Angelique (19 October 2011), "Tunisian elections: the key parties", The Guardian, retrieved 24 October 2011

- Bollier, Sam (9 Oct 2011), "Who are Tunisia's political parties?", Al Jazeera, retrieved 21 October 2011

- Walid Khéfifi. "Ettajdid : Ahmed Brahim succède à Harmel". Le Quotidien.

- Nadia Bentamansourt. "Ahmed Brahim n'est plus - African Manager". African Manager.

- "Ahmed Brahim troisième candidat de l'opposition à la présidence". Jeune Afrique. 24 March 2009.

- Ryan, Yasmine (26 January 2011). "How Tunisia's revolution began – Features". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 13 February 2011.

- "New Tunisian Constitution Adopted". Tunisia Live. 26 January 2014. Archived from the original on 27 January 2014. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- Tarek Amara (27 January 2014). "Arab Spring beacon Tunisia signs new constitution". Reuters. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "Tunisie : les législatives fixées au 26 octobre et la présidentielle au 23 novembre". Jeune Afrique. 25 June 2014.

- "Tunisia holds first post-revolution presidential poll". BBC News. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- النتائج النهائية للانتخابات التشريعية [Final results of parliamentary elections] (PDF) (in Arabic). 20 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- "A Snapshot of Corruption in Tunisia". Business Anti-Corruption Portal. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- Spencer, Richard (13 January 2011). "Tunisia riots: Reform or be overthrown, US tells Arab states amid fresh riots". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- Ryan, Yasmine. "Tunisia's bitter cyberwar". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- "Tunisia's Protest Wave: Where It Comes From and What It Means for Ben Ali | The Middle East Channel". Mideast.foreignpolicy.com. 3 January 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- Borger, Julian (29 December 2010). "Tunisian president vows to punish rioters after worst unrest in a decade". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- Tunisia suicide protester Mohammed Bouazizi dies, BBC, 5 January 2011.

- Fahim, Kareem (21 January 2011). "Slap to a Man's Pride Set Off Tumult in Tunisia". The New York Times. p. 2. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- Worth, Robert F. (21 January 2011). "How a Single Match Can Ignite a Revolution". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Davies, Wyre (15 December 2010). "Tunisia: President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali forced out". BBC News. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- "Uprising in Tunisia: People Power topples Ben Ali regime". Indybay. 16 January 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- "Trade unions: the revolutionary social network at play in Egypt and Tunisia". Defenddemocracy.org. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "The Nobel Peace Prize 2015 - Press Release". Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- Jihen Laghmari (25 July 2013). "Tunisia Party Leader Brahmi Shot Dead Outside His Home". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- Margaret Coker (26 July 2013). "Assassination Threatens New Tunisia Unrest". The Wall Street Journal: A8. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- Kumaran Ira (27 July 2013). "Tunisian opposition seizes on Brahmi's murder to push for Egypt-style coup". World Socialist Web Site. International Committee of the Fourth International. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- "Tunisie : obsèques sous tension du député Mohamed Brahmi". Le Monde. 27 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-07-28.

- "A new stage in left regroupment". Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Jano Charbel (13 October 2014). "The left of the Arab world". Mada Masr. Archived from the original on 17 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Popular Front is Born". Demotix. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Tunisie: Plus d'un million de Tunisiens aux obsèques de Chokri Belaïd". 20minutes.fr. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Tunisia pledges new govt after opposition leader's killing". Daily Star. 7 February 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- "Thousands attend funeral of Tunisian MP". Al Jazeera. 27 July 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- Daragahi, Borzou. Salafist identified as suspect in Tunisia assassination. Financial Times. 26 July 2013.

- Gall, Carlotta (26 July 2013). "Second Opposition Leader Assassinated in Tunisia". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 July 2013.