Manmohan Singh

Manmohan Singh (Punjabi: [mənˈmoːɦən ˈsɪ́ŋɡ] (![]()

Manmohan Singh | |

|---|---|

| |

| 13th Prime Minister of India | |

| In office 22 May 2004 – 26 May 2014 | |

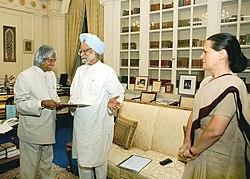

| President | A. P. J. Abdul Kalam Pratibha Patil Pranab Mukherjee |

| Preceded by | Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

| Succeeded by | Narendra Modi |

| 16th Minister of Personnel, Public Grievances and Pensions | |

| In office 23 May 2004 – 26 May 2014 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | Lal Krishna Advani |

| Succeeded by | Narendra Modi |

| Leader of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha | |

| In office 21 March 1998 – 21 May 2004 | |

| Prime Minister | Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

| Preceded by | Sikander Bakht |

| Succeeded by | Jaswant Singh |

| 22nd Minister of Finance | |

| In office 21 June 1991 – 16 May 1996 | |

| Prime Minister | P. V. Narasimha Rao |

| Preceded by | Yashwant Sinha |

| Succeeded by | Jaswant Singh |

| 14th Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission | |

| In office 15 January 1985 – 31 August 1987 | |

| Prime Minister | Rajiv Gandhi |

| Preceded by | P. V. Narasimha Rao |

| Succeeded by | P. Shiv Shankar |

| 15th Governor of the Reserve Bank of India | |

| In office 15 September 1982 – 15 January 1985 | |

| Preceded by | I. G. Patel |

| Succeeded by | Amitav Ghosh |

| Member of Parliament , Rajya Sabha | |

| Assumed office 19 August 2019 | |

| Preceded by | Madan Lal Saini |

| Constituency | Rajasthan |

| In office 1 October 1991[1] – 14 June 2019 | |

| Succeeded by | Kamakhya Prasad Tasa |

| Constituency | Assam |

| 5th Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India | |

| In office 1972–1976 | |

| Preceded by | Ashok Mitra |

| Succeeded by | R. M. Honavar |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 September 1932 Gah, Punjab, British India (present-day Punjab, Pakistan) |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Upinder, Daman, Amrit |

| Residence | 3 Motilal Nehru Marg, New Delhi[2][3] |

| Alma mater | Panjab University (BA, MA) University of Cambridge (BA) University of Oxford (DPhil) |

| Profession |

|

| Awards | Padma Vibushan Adam Smith Prize |

| Signature |  |

Born in Gah (now in Punjab, Pakistan), Singh's family migrated to India during its partition in 1947. After obtaining his doctorate in economics from Oxford, Singh worked for the United Nations during 1966–69. He subsequently began his bureaucratic career when Lalit Narayan Mishra hired him as an advisor in the Ministry of Commerce and Industry. During the 1970s and 1980s, Singh held several key posts in the Government of India, such as Chief Economic Advisor (1972–76), governor of the Reserve Bank (1982–85) and head of the Planning Commission (1985–87).

In 1991, as India faced a severe economic crisis, newly elected Prime Minister P. V. Narasimha Rao surprisingly inducted the apolitical Singh into his cabinet as Finance Minister. Over the next few years, despite strong opposition, he as a Finance Minister carried out several structural reforms that liberalised India's economy. Although these measures proved successful in averting the crisis, and enhanced Singh's reputation globally as a leading reform-minded economist, the incumbent Congress party fared poorly in the 1996 general election. Subsequently, Singh served as Leader of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha (the upper house of the Parliament of India) during the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government of 1998–2004.

In 2004, when the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) came to power, its chairperson Sonia Gandhi unexpectedly relinquished the premiership to Manmohan Singh. Singh's first ministry executed several key legislations and projects, including the Rural Health Mission, Unique Identification Authority, Rural Employment Guarantee scheme and Right to Information Act. In 2008, opposition to a historic civil nuclear agreement with the United States nearly caused Singh's government to fall after Left Front parties withdrew their support. Although India's economy grew rapidly under UPA I, its security was threatened by several terrorist incidents (including the 2008 Mumbai attacks) and the continuing Maoist insurgency.

The 2009 general election saw the UPA return with an increased mandate, with Singh retaining the office of Prime Minister. Over the next few years, Singh's second ministry government faced a number of corruption charges—over the organisation of the 2010 Commonwealth Games, the 2G spectrum allocation case and the allocation of coal blocks. After his term ended in 2014 he opted out from the race for the office of the Prime Minister of India during the 2014 Indian general election.[4] Singh was never a member of the Lok Sabha but served as a member of the Parliament of India, representing the state of Assam in the Rajya Sabha for five terms from 1991 to 2019.[5] In August 2019, Singh filed his nomination as a Congress candidate to the Rajya Sabha from Rajasthan after the death of sitting MP Madan Lal Saini.[6][7]

Early life and education

Singh was born to Gurmukh Singh and Amrit Kaur on 26 September 1932, in Gah, Punjab, British India, into a Sikh family.[8] He lost his mother when he was very young and was raised by his paternal grandmother, to whom he was very close.

After the Partition of India, his family migrated to Amritsar, India, where he studied at Hindu College. He attended Panjab University, then in Hoshiarpur,[9][10][11] Punjab, studying Economics and got his bachelor's and master's degrees in 1952 and 1954, respectively, standing first throughout his academic career. He completed his Economics Tripos at University of Cambridge as he was a member of St John's College in 1957.[12]

In a 2005 interview with the British journalist Mark Tully, Singh said about his Cambridge days:

I first became conscious of the creative role of politics in shaping human affairs, and I owe that mostly to my teachers Joan Robinson and Nicholas Kaldor. Joan Robinson was a brilliant teacher, but she also sought to awaken the inner conscience of her students in a manner that very few others were able to achieve. She questioned me a great deal and made me think the unthinkable. She propounded the left wing interpretation of Keynes, maintaining that the state has to play more of a role if you really want to combine development with social equity. Kaldor influenced me even more; I found him pragmatic, scintillating, stimulating. Joan Robinson was a great admirer of what was going on in China, but Kaldor used the Keynesian analysis to demonstrate that capitalism could be made to work.[13]

After Cambridge, Singh returned to India to his teaching position at Punjab University.[14]

In 1960, he went to the University of Oxford for the DPhil, where he was a member of Nuffield College. His 1962 doctoral thesis under the supervision of I.M.D. Little was titled "India's export performance, 1951–1960, export prospects and policy implications", and was later the basis for his book "India's Export Trends and Prospects for Self-Sustained Growth".[15]

Early career

After completing his D.Phil., Singh returned to India. He was a senior lecturer of economics at Panjab University from 1957 to 1959. During 1959 and 1963, he served as a reader in economics at Panjab University, and from 1963 to 1965, he was an economics professor there.[16] Then he went to work for the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) from 1966–1969.[12] Later, he was appointed as an advisor to the Ministry of Foreign Trade by Lalit Narayan Mishra, in recognition of Singh's talent as an economist.[17]

From 1969 to 1971, Singh was a professor of international trade at the Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi.[12][18]

In 1972, Singh was chief economic adviser in the Ministry of Finance, and in 1976 he was secretary in the Finance Ministry.[12] In 1980–1982 he was at the Planning Commission, and in 1982, he was appointed governor of the Reserve Bank of India under then finance minister Pranab Mukherjee and held the post until 1985.[12] He went on to become the deputy chairman of the Planning Commission (India) from 1985 to 1987.[8] Following his tenure at the Planning Commission, he was secretary general of the South Commission, an independent economic policy think tank headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland from 1987 to November 1990.[19]

Singh returned to India from Geneva in November 1990 and held the post as the advisor to Prime Minister of India on economic affairs during the tenure of V. P. Singh.[12] In March 1991, he became chairman of the University Grants Commission.[12]

Political career

In June 1991, India's prime minister at the time, P. V. Narasimha Rao, chose Singh to be his finance minister. Singh told Mark Tully the British journalist in 2005 "On the day (Rao) was formulating his cabinet, he sent his Principal Secretary to me saying, 'The PM would like you to become the Minister of Finance'. I didn't take it seriously. He eventually tracked me down the next morning, rather angry, and demanded that I get dressed up and come to Rashtrapati Bhavan for the swearing in. So that's how I started in politics".[14]

Minister of Finance

In 1991, India's fiscal deficit was close to 8.5 per cent of the gross domestic product, the balance of payments deficit was huge and the current account deficit was close to 3.5 percent of India's GDP.[20] India's foreign reserves barely amounted to US$1 billion, enough to pay for 2 weeks of imports,[21] in comparison to US$283 billion today.[22]

Evidently, India was facing an economic crisis. At this point, the government of India sought funds from the supranational International Monetary Fund, which, while assisting India financially, imposed several conditions regarding India's economic policy. In effect, IMF-dictated policy meant that the ubiquitous Licence Raj had to be dismantled, and India's attempt at a state-controlled economy had to end.

Manmohan explained to the PM and the party that India is facing an unprecedented crisis.[21] However the rank and file of the party resisted deregulation.[21] So Chidambaram and Manmohan explained to the party that the economy would collapse if it was not deregulated.[21] To the dismay of the party, Rao allowed Manmohan to deregulate the Indian economy.[21]

Subsequently, Singh, who had thus far been one of the most influential architects of India's socialist economy, eliminated the permit raj,[21] reduced state control of the economy, and reduced import taxes[20][23]

Rao and Singh thus implemented policies to open up the economy and change India's socialist economy to a more capitalistic one, in the process dismantling the Licence Raj, a system that inhibited the prosperity of private businesses. They removed many obstacles standing in the way of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and initiated the process of the privatisation of public sector companies. However, in spite of these reforms, Rao's government was voted out in 1996 due to non-performance of government in other areas. In praise of Singh's work that pushed India towards a market economy, long-time Cabinet minister P. Chidambaram has compared Singh's role in India's reforms to Deng Xiaoping's in China.[24]

In 1993, Singh offered his resignation from the post of Finance Minister after a parliamentary investigation report criticised his ministry for not being able to anticipate a US$1.8 billion securities scandal. Prime Minister Rao refused Singh's resignation, instead promising to punish the individuals directly accused in the report.[25]

Leader of Opposition in Rajya Sabha

Singh was first elected to the upper house of Parliament, the Rajya Sabha, in 1991[26] by the legislature of the state of Assam, and was re-elected in 1995, 2001, 2007[8] and 2013.[27] From 1998 to 2004, while the Bharatiya Janata Party was in power, Singh was the Leader of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha. In 1999, he contested for the Lok Sabha from South Delhi but was unable to win the seat.[28]

Prime Minister of India

| Wikinews has related news: |

14th Lok Sabha

After the 2004 general elections, the Indian National Congress ended the incumbent National Democratic Alliance (NDA) tenure by becoming the political party with the single largest number of seats in the Lok Sabha. It formed United Progressive Alliance (UPA) with allies and staked claim to form government. In a surprise move, Chairperson Sonia Gandhi declared Manmohan Singh, a technocrat, as the UPA candidate for the Prime Ministership. Despite the fact that Singh had never won a Lok Sabha seat, according to the BBC, he "has enjoyed massive popular support, not least because he was seen by many as a clean politician untouched by the taint of corruption that has run through many Indian administrations."[29] He took the oath as the Prime Minister of India on 22 May 2004.[30][31]

Economic policy

In 1991, Singh as Finance Minister, freed India from the Licence Raj, source of slow economic growth and corruption in the Indian economy for decades. He liberalised the Indian economy, allowing it to speed up development dramatically. During his term as Prime Minister, Singh continued to encourage growth in the Indian market, enjoying widespread success in these matters. Singh, along with the former Finance Minister, P. Chidambaram, has presided over a period where the Indian economy has grown with an 8–9% economic growth rate. In 2007, India achieved its highest GDP growth rate of 9% and became the second fastest growing major economy in the world.[32][33] Singh's ministry enact a National Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in 2005.

Singh's government has continued the Golden Quadrilateral and the highway modernisation program that was initiated by Vajpayee's government.[34] Singh has also been working on reforming the banking and financial sectors, as well as public sector companies.[35] The Finance ministry has been working towards relieving farmers of their debt and has been working towards pro-industry policies.[36] In 2005, Singh's government introduced the value added tax, replacing sales tax. In 2007 and early 2008, the global problem of inflation impacted India.[37]

Healthcare and education

In 2005, Prime Minister Singh and his government's health ministry started the National Rural Health Mission (NHRM), which has mobilised half a million community health workers. This rural health initiative was praised by the American economist Jeffrey Sachs.[38] In 2006, his Government implemented the proposal to reserve 27% of seats in All India Institute of Medical Studies (AIIMS), Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) and other central institutions of higher education for Other Backward Classes which led to 2006 Indian anti-reservation protests.

On 2 July 2009, Singh ministry introduced The Right to Education Act (RTE) act. Eight IIT's were opened in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Orissa, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Himachal Pradesh.[39] The Singh government also continued the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan programme. The programme includes the introduction and improvement of mid-day meals and the opening of schools all over India, especially in rural areas, to fight illiteracy.[40]

Security and Home Affairs

Singh's government has been instrumental in strengthening anti-terror laws with amendments to Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). National Investigation Agency (NIA) was also created soon after the Nov 2008 Mumbai terror attacks, as need for a central agency to combat terrorism was realised. Also, Unique Identification Authority of India was established in February 2009, an agency responsible for implementing the envisioned Multipurpose National Identity Card with the objective of increasing national security and facilitating e-governance.

Singh's administration initiated a massive reconstruction effort in Kashmir to stabilise the region but after some period of success, insurgent infiltration and terrorism in Kashmir has increased since 2009.[41] However, the Singh administration has been successful in reducing terrorism in Northeast India.[41]

Legislations

The important National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) and the Right to Information Act were passed by the Parliament in 2005 during his tenure. While the effectiveness of the NREGA has been successful at various degrees, in various regions, the RTI act has proved crucial in India's fight against corruption.[42] New cash benefits[43] were also introduced for widows, pregnant women, and landless persons.[44]

The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 was passed on 29 August 2013 in the Lok Sabha (lower house of the Indian parliament) and on 4 September 2013 in Rajya Sabha (upper house of the Indian parliament). The bill received the assent of the President of India, Pranab Mukherjee on 27 September 2013.[45] The Act came into force from 1 January 2014.[46][47][48]

Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act was enacted on 4 August 2009, which describes the modalities of the importance of free and compulsory education for children between 6 and 14 in India under Article 21A of the Indian Constitution.[49] India became one of 135 countries to make education a fundamental right of every child when the act came into force on 1 April 2010.[50][51][52]

Foreign policy

.jpg)

Manmohan Singh has continued the pragmatic foreign policy that was started by P.V. Narasimha Rao and continued by Bharatiya Janata Party's Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Singh has continued the peace process with Pakistan initiated by his predecessor, Atal Bihari Vajpayee. Exchange of high-level visits by top leaders from both countries have highlighted his tenure. Efforts have been made during Singh's tenure to end the border dispute with People's Republic of China. In November 2006, Chinese President Hu Jintao visited India which was followed by Singh's visit to Beijing in January 2008. A major development in Sino-Indian relations was the reopening of the Nathula Pass in 2006 after being closed for more than four decades.[53] Premier of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China, Li Keqiang paid a state visit to India (Delhi-Mumbai) from 19–21 May 2013.[53] Singh paid an official visit to China from 22–24 October 2013.[53] Signed were three agreements establishing sister-city partnership between Delhi-Beijing, Kolkata-Kunming and Bangalore-Chengdu. As of 2010, the People's Republic of China is the second biggest trade partner of India.[54]

Relations with Afghanistan have improved considerably, with India now becoming the largest regional donor to Afghanistan.[55] During Afghan President Hamid Karzai's visit to New Delhi in August 2008, Manmohan Singh increased the aid package to Afghanistan for the development of more schools, health clinics, infrastructure, and defence.[56] Under the leadership of Singh, India has emerged as one of the single largest aid donors to Afghanistan.[56]

Singh's government has worked towards stronger ties with the United States. He visited the United States in July 2005 initiating negotiations over the Indo-US civilian nuclear agreement. This was followed by George W. Bush's successful visit to India in March 2006, during which the declaration over the nuclear agreement was made, giving India access to American nuclear fuel and technology while India will have to allow IAEA inspection of its civil nuclear reactors. After more than two years for more negotiations, followed by approval from the IAEA, Nuclear Suppliers Group and the US Congress, India and the US signed the agreement on 10 October 2008 with Pranab Mukherjee representing India.[57] Singh had the first official state visit to the White House during the administration of US President Barack Obama. The visit took place in November 2009, and several discussions took place, including on trade and nuclear power.[58]

Relations have improved with Japan and European Union countries, like the United Kingdom, France, and Germany. Relations with Iran have continued and negotiations over the Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline have taken place. New Delhi hosted an India–Africa Summit in April 2006 which was attended by the leaders of 15 African states.[59] Relations have improved with other developing countries, particularly Brazil and South Africa. Singh carried forward the momentum which was established after the "Brasilia Declaration" in 2003 and the IBSA Dialogue Forum was formed.[60]

Singh's government has also been especially keen on expanding ties with Israel. Since 2003, the two countries have made significant investments in each other[61] and Israel now rivals Russia to become India's defence partner.[62] Though there have been a few diplomatic glitches between India and Russia, especially over the delay and price hike of several Russian weapons to be delivered to India,[63] relations between the two remain strong with India and Russia signing various agreements to increase defence, nuclear energy and space co-operation.[64]

15th Lok Sabha

India held general elections to the 15th Lok Sabha in five phases between 16 April 2009 and 13 May 2009. The results of the election were announced on 16 May 2009.[65] Strong showing in Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh helped the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) form the new government under the incumbent Singh, who became the first prime minister since Jawaharlal Nehru in 1962 to win re-election after completing a full five-year term.[66] The Congress and its allies were able to put together a comfortable majority with support from 322 members out of 543 members of the House. These included those of the UPA and the external support from the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), Samajwadi Party (SP), Janata Dal (Secular) (JD(S)), Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and other minor parties.[67]

On 22 May 2009, Manmohan Singh was sworn in as the Prime Minister during a ceremony held at Rashtrapati Bhavan.[68][69] The 2009 Indian general election was the largest democratic election in the world held to date, with an eligible electorate of 714 million.

The 2012 report filed by the CAG in Parliament of India states that due to the allocation of coal blocks to certain private companies without bidding process the nation suffered an estimated loss of Rs 1.85 trillion (short scale) between 2005 and 2009 in which Manmohan Singh was the coal minister of India.[70][71]

Manmohan Singh declined to appear before a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) in April 2013 when called upon by one of the members of JPC Yashwant Sinha for his alleged involvement in the 2G case.[72]

16th Lok Sabha

Singh did not contest the 2014 general election for the 16th Lok Sabha and resigned his post as prime minister at the end of his term on 17 May 2014. He served as the acting prime minister till 25 May 2014, when Narendra Modi was sworn in as the new prime minister.[73][74][75]

Post-premiership

In 2016 it was announced that Singh was to take up a position at Panjab University as the Jawaharlal Nehru Chair.[76]

Public image

The Independent described Singh as "one of the world's most revered leaders" and "a man of uncommon decency and grace," noting that he drives a Maruti 800, one of the humblest cars in the Indian market. Khushwant Singh lauded Singh as the best prime minister India has had, even rating him higher than Jawaharlal Nehru. He mentions an incident in his book Absolute Khushwant: The Low-Down on Life, Death and Most things In-between where after losing the 1999 Lok Sabha elections, Singh immediately returned the ₹2 lakh (US$2,800) he had borrowed from the writer for hiring taxis. Terming him as the best example of integrity, Khushwant Singh stated, "When people talk of integrity, I say the best example is the man who occupies the country's highest office."[77]

In 2010, Newsweek magazine recognised him as a world leader who is respected by other heads of state, describing him as "the leader other leaders love." The article quoted Mohamed ElBaradei, who remarked that Singh is "the model of what a political leader should be."[78] Singh also received the World Statesman Award in 2010. Henry Kissinger described Singh as "a statesman with vision, persistence and integrity", and praised him for his "leadership, which has been instrumental in the economic transformation underway in India."[79]

Manmohan Singh was ranked 18 on the 2010 Forbes list of the world's most powerful people.[80] Forbes magazine described Singh as being "universally praised as India's best prime minister since Nehru".[81] Australian journalist Greg Sheridan praised Singh "as one of the greatest statesmen in Asian history."[82] Singh was later ranked 19 and 28 in 2012 and 2013 in Forbes list.[83][84][85]

Time magazine's Asia edition for 10–17 July 2012 week, on its cover remarked that Singh was an "underachiever".[86] It stated that Singh appears "unwilling to stick his neck out" on reforms that will put the country back on growth path. Congress spokesperson, Manish Tiwari rebutted the charges. UPA ally Lalu Prasad Yadav took issue with the magazine's statements. Praising the government, Prasad said UPA projects [were] doing well and asked, "What will America say as their own economy is shattered?".[87]

Political opponents including L. K. Advani have claimed that Singh is a "weak" Prime Minister. Advani declared "He is weak. What do I call a person who can't take his decisions until 10 Janpath gives instruction."[88][89][90] The Independent also claimed that Singh did not have genuine political power.[91]

Singh's public image had been tarnished with his coalition government having been accused of various corruption scandals since the start of its second term in 2009.[92] Opposition demanded his resignation for his alleged inaction and indecisiveness in 2G spectrum case[93] and Indian coal allocation scam.[94] Senior MP of the Communist Party of India Gurudas Dasgupta accused Manmohan Singh of "Dereliction of duty", alleging that he (the PM) was fully aware of irregularities in dispensing of 2G telecom licences.[95]

His party, the Indian National Congress, was criticised by the Supreme Court for appointing P.J. Thomas as the CVC chief, while there was an ongoing corruption enquiry against the same individual in the Palmolein Oil Import Scam. Manmohan Singh has come in for severe criticism for remaining silent on the matter.[96] Singh was also criticised for allowing allocation of S-band spectrum without any bidding to ISRO by an agreement. The agreement was between Devas multimedia, a private firm and Antrix Corporation, a commercial wing of ISRO.[97]

He has been largely viewed as accepting the role as "seat warmer" for Rahul Gandhi; this was felt to have undercut the institution of the prime minister.[98]

Family and personal life

Singh married Gursharan Kaur in 1958. They have three daughters, Upinder Singh, Daman Singh and Amrit Singh.[99] Upinder Singh is a professor of history at Delhi University. She has written six books, including Ancient Delhi (1999) and A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India (2008). Daman Singh is a graduate of St. Stephen's College, Delhi and Institute of Rural Management, Anand, Gujarat, and author of The Last Frontier: People and Forests in Mizoram and a novel Nine by Nine,[100] Amrit Singh is a staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union.[101] Ashok Pattnaik, 1983 batch Indian Police Service officer, son-in-law of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, was appointed CEO of National Intelligence Grid (NATGRID) in 2016.[102]

Singh has undergone multiple cardiac bypass surgeries, the most recent of which took place in January 2009.[103]

Degrees and posts held

- B.A (Honours) in Economics 1952; M.A (First Class) in Economics, 1954 Panjab University, Chandigarh (then in Hoshiarpur, Punjab), India

- Honours degree in Economics, University of Cambridge – St John's College (1957)

- Senior Lecturer, Economics (1957–1959)

- Reader (1959–1963)

- Professor (1963–1965)

- Professor of International Trade (1969–1971)

- DPhil in Economics, University of Oxford – Nuffield College (1962)

- Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi

- Honorary Professor (1966)

- Chief, Financing for Trade Section, UNCTAD, United Nations Secretariat, New York

- 1966 : Economic Affairs Officer 1966

- Economic Adviser, Ministry of Foreign Trade, India (1971–1972)

- Chief Economic Adviser, Ministry of Finance, India, (1972–1976)

- Honorary Professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi (1976)

- Director, Reserve Bank of India (1976–1980)

- Director, Industrial Development Bank of India (1976–1980)

- Board of Governors, Asian Development Bank, Manila

- Secretary, Ministry of Finance (Department of Economic Affairs), Government of India, (1977–1980)

- Governor, Reserve Bank of India (1982–1985)

- Deputy chairman, Planning Commission of India, (1985–1987)

- Secretary General, South Commission, Geneva (1987–1990)

- Advisor to Prime Minister of India on Economic Affairs (1990–1991)

- Chairman, University Grants Commission (15 March 1991 – 20 June 1991)[8]

- Finance Minister of India, (21 June 1991 – 15 May 1996)

- Leader of the Opposition (India) in the Rajya Sabha (1998–2004)

- Prime Minister of India (22 May 2004 – 26 May 2014)

Honours, awards and international recognition

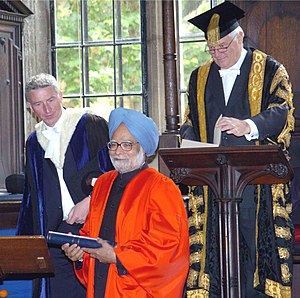

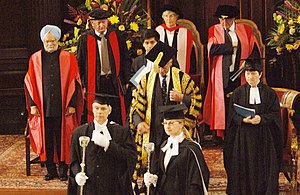

In March 1983, Panjab University awarded him Doctor of Letters and in 2009 created a Dr. Manmohan Singh chair in their economics department.[104] In 1997, the University of Alberta awarded him an honorary Doctor of Law degree.[105] The University of Oxford awarded him an honorary Doctor of Civil Law degree in July 2005,[106] and in October 2006, the University of Cambridge followed with the same honour.[107] St. John's College further honoured him by naming a PhD Scholarship after him, the Dr. Manmohan Singh Scholarship.[108] In 2008, he was awarded honorary Doctor of Letters degree by Benaras Hindu University[109] and later that year he was awarded an honorary doctorate degree by University of Madras.[110] In 2010, he was awarded honorary doctorate degree by King Saud University[111] and in 2013, he was awarded honorary doctorate degree by Moscow State Institute of International Relations.[112] In 2017 awarded Indira Gandhi Prize for Peace, Disarmament and Development.

He has also received honorary doctorates from University of Bologna, University of Jammu and Indian Institute of Technology Roorkee.[113]

| Year | Name of award or honour | Awarding organisation |

|---|---|---|

| 1952 | University Medal for standing first in B.A. (Honors Economics)[12] | Panjab University, Chandigarh |

| 1954 | Uttar Chand Kapur Medal, for standing first in M.A. (Economics)[12] | Panjab University, Chandigarh {Was then in Hoshiarpur, Punjab} |

| 1955 | Wright Prize for Distinguished Performance[12] | St. John's College, Cambridge, UK |

| 1956 | Adam Smith Prize[12] | University of Cambridge, UK |

| 1957 | Elected Wrenbury Scholar[12] | University of Cambridge, UK |

| 1976 | Honorary Professorship[12] | Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi |

| 1982 | Elected Honorary Fellow, Indian Institute of Bankers[12] | Indian Institute of Bankers |

| 1982 | Elected Honorary Fellow, St. John's College[12] | St John's College, Cambridge |

| 1985 | Elected President of the Indian Economic Association[12] | Indian Economic Association |

| 1986 | Elected National Fellow, National Institute of Education[12] | National Institute of Education |

| 1987 | Padma Vibhushan[12] | President of India |

| 1993 | Finance Minister of the Year[12] | Asiamoney |

| 1993 | Finance Minister of the Year[12] | Euromoney |

| 1994 | Elected Honorary Fellow of the All India Management Association[12] | All India Management Association |

| 1994 | Elected Distinguished Fellow of the London School of Economics[12] | London School of Economics, Centre for Asia Economy, Politics and Society |

| 1994 | Elected Honorary Fellow, Nuffield College[12] | Nuffield College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK |

| 1994 | Elected Distinguished Fellow of the London School of Economics[12] | London School of Economics, Centre for Asia Economy, Politics and Society |

| 1994 | Jawaharlal Nehru Birth Centenary Award (1994–95)[12] | Indian Science Congress Association. |

| 1994 | Finance Minister of the Year[12] | Asiamoney |

| 1995 | Jawaharlal Nehru Birth Centenary Award (1994–95)[12] | Indian Science Congress Association |

| 1996 | Honorary Professorship[12] | Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, Delhi |

| 1997 | Nikkei Asia prize for Regional Growth[12] | Nihon Keizai Shimbun Inc. |

| 1997 | Justice K.S. Hegde Foundation Award[12] | Justice K.S. Hegde Foundation |

| 1997 | Lokmanya Tilak Award[12] | Tilak Smarak Trust, Pune |

| 1999 | Fellow of the National Academy of Agricultural Sciences, New Delhi[12] | National Academy of Agricultural Sciences |

| 1999 | H.H. Kanchi Sri Paramacharya Award for Excellence[12] | Shri R. Venkataraman, The Centenarian Trust |

| 2000 | Annasaheb Chirmule Award[12] | Annasaheb Chirmule Trust |

| 2002 | Outstanding Parliamentarian Award[114] | Indian Parliamentary Group |

| 2005 | Honorary Fellowship[115] | All India Institute of Medical Sciences |

| 2005 | Top 100 Influential People in the World[116] | Time |

| 2010 | World Statesman Award[79] | Appeal of Conscience Foundation |

| 2014 | Grand Cordon of the Order of the Paulownia Flowers[117] | Government of Japan |

See also

- Dr Manmohan Singh Scholarship at the University of Cambridge

- Economic reforms under Manmohan Singh

- First Manmohan Singh ministry

- United Progressive Alliance

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Atal Bihari Vajpayee |

Prime Minister of India 22 May 2004 – 26 May 2014 |

Succeeded by Narendra Modi |

References

- "Prime Minister Manmohan Singh files Rajya Sabha nomination papers amid protests". NDTV. 15 May 2013. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- "Former PM Manmohan Singh moves to 3, Motilal Nehru Marg".

- http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/manmohan-singh-moves-into-new-house-on-3-motilal-nehru-marg/article

- "India's Manmohan Singh to step down as PM". The Guardian. 3 January 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- "Manmohan Singh takes oath as Rajya Sabha member". The Times of India. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- Iqbal, Mohammed (13 August 2019). "Manmohan Singh files Rajya Sabha nomination from Rajasthan". The Hindu. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "RS bypoll: Manmohan's nomination found valid". The Tribune. 17 August 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- "Detailed Profile: Dr. Manmohan Singh". Archived from the original on 7 December 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- "Government College, Hoshiarpur | Colleges in Hoshiarpur Punjab". Punjabcolleges.com. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Three sardars and their Hoshiarpur connection". Portal.bsnl.in. 23 March 1932. Archived from the original on 28 November 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Hoshiarpur". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012.

- "Curriculum Vitae of Prime Minister of India". CSIR. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- "Manmohan Singh - PIB". Press Information Bureau. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Mark Tully. "Architect of the New India". Cambridge Alumni Magazine. Michaelmas 2005. Retrieved on 28 February 2013. Archived 1 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Curriculum Vitae" (PDF). Prime Minister's Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- Bhushan, K.; Katyal, G. (2004). Manmohan Singh: Visionary to Certainty. APH Publishing Corporation. p. 2. ISBN 978-8176486941. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- "Manmohan Singh". India Today. Living Media India Limited. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Detailed Profile: Dr. Manmohan Singh". india.gov.in. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- "India – Head of Government". Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- rediff Business Desk (26 September 2005). "Manmohan Singh: Father of Indian Reform". Rediff.com. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- "Commanding Heights : Episode 2 | on PBS". Pbs.org. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- Mahalakshmi Hariharan (2 January 2010). "Forex reserves swell 11% in 2009". Yahoo Finance India. Archived from the original on 3 January 2010. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- Friedman, Thomas L. (2008). The World is Flat – A brief history of the twenty-first century. Picador. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-374-29288-1.

- "Manmohan is Deng Xiaoping of India: P Chidambaram – Oneindia News". News.oneindia.in. 2 May 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "Indian Leader Bars Key Aide From Quitting in Stock Scam". The New York Times. 1 January 1994. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- "Profile: Prime Minister India". Indian gov. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2009.

- "PM Manmohan Singh elected to Rajya Sabha". Zee News Limited. 30 May 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Candidate Statistics Manmohan Singh". IBN Live. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2009.

- "Profile: Manmohan Singh". BBC News. 30 March 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- "Manmohan to Advani: Change your astrologers, stop abuse against me". Thaindian News. 22 July 2008. Retrieved 23 July 2008.

- "Manmohan takes on Advani: Babri destruction his only contribution". Southasia Times. 25 March 2009.

- "CIA – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "The India Report" (PDF). Astaire Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 January 2009.

- "Economic benefits of golden Quadilateral". Business today. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Banking on reform". Indian Express. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Farmer Waiver Scheme- PM statement". PIB. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Kevin Plumberg; Steven C. Johnson (2 November 2008). "Global inflation climbs to historic levels". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- Sachs, Jeffrey D. (6 March 2005). "The End of Poverty". Time.

- "LS passes bill to provide IIT for eight states". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Direct SSA funds for school panels". Deccan Herald. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- Infiltration has not reduced in Kashmir, insurgency down in North East: Chidambaram Archived 7 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "RTI Act: A strong tool to cleanse corruption in India". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---gender/documents/publication/wcms_233599.pdf

- Ltd, Career Launcher India (1 November 2009). India Business Yearbook 2009. Vikas Publishing House Pvt Limited. ISBN 9788125930860. Retrieved 16 November 2016 – via Google Books.

- "President Pranab Mukherjee gives nod to Land Acquisition Bill". NDTV. 27 September 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Gazette Notification of coming into force of the Act" (PDF). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- "The New Land Acquisition Act to come into effect from 2014". Economic Times. 16 October 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- "Land Acquisition bill to be notified early next year: Jairam Ramesh". Economic Times. 15 September 2013. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Provisions of the Constitution of India having a bearing on Education". Department of Higher Education. Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- Aarti Dhar (1 April 2010). "Education is a fundamental right now". The Hindu.

- "India launches children's right to education". BBC News. 1 April 2010.

- "India joins list of 135 countries in making education a right". The Hindu. The Hindu News. 2 April 2010.

- "Visits of Heads of States/Heads of Governments" (PDF). Ministry of External Affairs (India). Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "China becomes India's 2nd largest trade partner - People's Daily Online". Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Bajoria, Jayshree (23 October 2008). "India-Afghanistan Relations". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 29 November 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- "BBC NEWS - South Asia - India announces more Afghan aid". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "U.S., India ink historic civilian nuclear deal". People's Daily. 11 October 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- "Manmohan Singh's U.S. Visit". Centre for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Several African leaders to attend Africa-India summit, AU says". African Press International. 28 March 2008. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- Beri, Ruchita (10 December 2008). "IBSA Dialogue Forum: A Strategic Partnership". The African Executive. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- Halarnkar, Samar (23 October 2007). "India and Israel: The great seduction". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- Waldman, Amy (7 September 2003). "The Bond Between India and Israel Grows". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- Dikshit, Sandeep (17 April 2008). "Centre admits to problems in naval deals". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- Roychowdhury, Amitabh (6 December 2006). "India, Russia sign agreements to further strengthen ties". Outlook. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- "India's ruling party wins resounding victory". Associated Press. 16 May 2009. Archived from the original on 6 December 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- "Second UPA win, a crowning glory for Sonia's ascendancy". Business Standard. 16 May 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- "Smooth sailing for UPA, parties scramble to support". CNN-IBN. 19 May 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- "Team Manmohan set to form govt today". Times Now. 22 May 2009. Archived from the original on 27 May 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- "India PM Singh takes oath for second term". Reuters. 22 May 2009. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- Nairita (18 August 2012). "Coalgate scam: PM Manmohan Singh asked to resign". Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- "Prime Minister Manmohan Singh directly responsible for coal scam: Arun Jaitley". The Economic Times. PTI. 19 August 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- "2G scam: Disappointed over Manmohan Singh's refusal to appear before JPC, says Yashwant Sinha". DNA India. ANI. 9 April 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- "Prime Minister Manmohan Singh Resigns After 10 Years in Office". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "Manmohan Singh to continue as PM till Modi assumes office". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "Manmohan Singh resigns bringing to an end his 10-year tenure - Times of India". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "Former PM Manmohan Singh returns to teaching". Asian Voice. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- "PM Manmohan Singh: PM Manmohan Singh is the best example of integrity: Khushwant Singh | India News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- Christopher Dickey (16 August 2010). "Go to the Head of the Class". Newsweek. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- PTI (23 September 2010). "Manmohan Singh honoured with 2010 World Statesman Award". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- "The World's Most Powerful People: Manmohan Singh". Forbes. 3 November 2010.

- "The World's Most Powerful People: Sonia Gandhi". Forbes. 3 November 2010.

- "Strengthen Team India". The Australian. 21 May 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- "Manmohan Singh". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Tharakan, By Tony (31 October 2013). "Sonia Gandhi, Manmohan Singh slip in Forbes' most powerful list". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "These are the world's most powerful people, Photo Gallery". Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "Time magazine dubs Manmohan Singh as 'underachiever'". The Times of India. 8 July 2012.

- "Cong counters Time magazine's 'underachiever' remark against PM". 8 July 2012.

- "Manmohan Singh is a weak PM, reiterates Advani : East News – India Today". Retrieved 17 May 2012.. Indiatoday.intoday.in (21 October 2011). Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Manmohan Singh weak PM, unbecoming of the coveted post: BJP – India – DNA". Retrieved 17 May 2012.. Dnaindia.com (21 January 2012). Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Dangerous to have a weak PM: Anna". Retrieved 17 May 2012.. Zeenews.india.com (9 December 2011). Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- "Saviour or Sonia's poodle, asks UK paper about PM Manmohan Singh". The Times of India. 17 July 2012.

- "India's corruption scandals". BBC. 18 April 2012.

- The silence of the lamb | Ashish Khetan Archived 7 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Tehelka.com. Retrieved on 16 July 2013.

- Is Prime Minister Manmohan Singh actually a very astute politician? | Shoma Chaudhury Archived 31 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Tehelka.com. Retrieved on 16 July 2013.

- Gurudas Dasgupta rubbishes JPC report on 2G scam. The Hindu (21 April 2013). Retrieved on 16 July 2013.

- "Congress silent on CVC row". The Hindu. 23 November 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "An ignorant prime minister is a serious matter: BJP". 14 February 2011.

- "Victor in India Promises to Make Country Strong". The New York Times. 18 May 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- "Dr. Manmohan Singh: Personal Profile". Prime Minister's Office, Government of India. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- "Meet Dr. Singh's daughter". Rediff.com. 28 January 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- Rajghatta, Chidanand (21 December 2007). "PM's daughter puts White House in the dock". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- "An NDA boost for NATGRID, Home Minister reviews progress". India Today. New Delhi, India. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "One graft successfully performed on Manmohan Singh". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 24 January 2009. Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- "What happened to PM's honorary degree?". The New Indian Express. India. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- "India's former finance minister among honorary degree recipients". sites.ualberta.ca. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- "Oxford University confers doctorate degree on Manmohan Singh". Archived from the original on 28 November 2011.

- Roy, Amit (15 October 2006). "Cambridge University confers doctorate degree on Manmohan Singh". The Telegraph.

- to apply for a Manmohan Singh Undergraduate Scholarship., Applicants to the University from India may be eligible (11 October 2018). "Manmohan Singh Scholarships for applicants from India". study.cam.ac.uk.

- "Manmohan Singh awarded honorary doctorate degree by BHU". The Times of India. 15 March 2008.

- "Manmohan Singh conferred honorary doctorate degree by Madras University". 5 September 2008.

- "Manmohan conferred honorary doctorate by King Saud University". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 1 March 2010.

- "Prime Minister Manmohan Singh conferred Honorary Doctorate by Russian institute". The Economic Times. 21 October 2013.

- "Manmohan Singh is 'doctor' once again". Hindustan Times. India. 14 July 2007. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- "Indian Parliamentary Group". p. 1. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- "Explore ways to improve the health status of the country: PM". Press Information Bureau. 18 April 2005. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- Sen, Amartya (18 April 2005). "Manmohan Singh: The 2005 TIME 100". Time. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- PTI (3 November 2014). "Manmohan Singh chosen for Japan national award". The Hindu. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manmohan Singh. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Manmohan Singh |

- Prime Minister Manmohan Singh Prime Ministers Office, Archived

- Profile and CV of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh Prime Ministers Office, Archived

- Cabinet of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh Prime Ministers Office, Archived

- Appearances on C-SPAN