Chittagong

Chittagong (/tʃɪtəɡɒŋ/), officially Chattogram (Bengali: চট্টগ্রাম)[5] and known as the Port City of Bangladesh, is a major coastal city and financial centre in southeastern Bangladesh. The city has a population of more than 2.5 million[3] while the metropolitan area had a population of 4,009,423 in 2011,[3] making it the second-largest city in the country. It is the capital of an eponymous District and Division. The city is located on the banks of the Karnaphuli River between the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the Bay of Bengal. Modern Chittagong is Bangladesh's second most significant urban center after Dhaka.

Chittagong চট্টগ্রাম Chattogram | |

|---|---|

.jpg) From top: Chittagong Skyline, Chittagong War Cemetery, Shah Amanat Bridge, Foy's Lake, Ethnological Museum of Chittagong, Port of Chittagong & Karnaphuli River | |

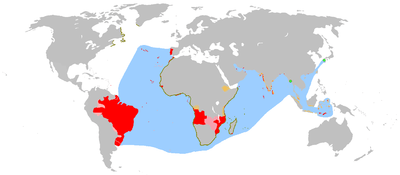

Chittagong Location of Chittagong in Bangladesh  Chittagong Chittagong (Bangladesh)  Chittagong Chittagong (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 22°20′06″N 91°49′57″E | |

| Country | |

| Division | Chittagong Division |

| District | Chittagong District |

| Establishment | 1340 |

| Granted city status | 1863[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Body | Chattogram City Corporation |

| • City Mayor | A J M Nasir Uddin |

| Area | |

| • Metropolis | 5,282.92 km2 (2,039.75 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,054.90 km2 (793.40 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,510 km2 (980.2 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 29 m (95 ft) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Metropolis | 3,116,000[3] |

| • Density | 19,800/km2 (51,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 6,025,985 |

| • Urban density | 19,800/km2 (51,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 9,453,496 |

| • Metro density | 3,187/km2 (8,250/sq mi) |

| • Demonym | Chittagonian; also (colloquial): Chottogrami, Chatigaiya, Sitainga, Chittagainga |

| • Population growth rate | 2.8% |

| Demonym(s) | Chatgaiya/sãṭgãiya (চাঁটগাঁইয়া) |

| Time zone | UTC+6 (BST) |

| Postal code | 4000, 4100, 42xx |

| Calling code | +880 31 |

| Police | Chittagong Metropolitan Police |

| Metro GDP/PPP (2018) | |

| International airport | Shah Amanat International |

| Voter (2018) | 5,632,322 |

| Website | Chittagong City Corporation |

Chittagong plays a vital role in the Bangladeshi economy. The Port of Chittagong, one of the world's oldest ports,[6] whose coast appeared on Ptolemy's world map, is the principal maritime gateway to the country. The port is the busiest international seaport on the Bay of Bengal and the third busiest in South Asia.[7] The Chittagong Stock Exchange is one of the country's two stock markets. Several Chittagong-based companies are among the largest industrial conglomerates and enterprises in Bangladesh. The port city is the largest base of the Bangladesh Navy and Bangladesh Coast Guard; while the Bangladesh Army and Bangladesh Air Force also maintains bases and contributes to the city's economy. Chittagong is the headquarters of the Eastern Zone of the Bangladesh Railway, having historically been the headquarters of British India's Assam Bengal Railway and East Pakistan's Pakistan Eastern Railway. A controversial ship breaking industry on the outskirts of the city, which supplies local steel but causes pollution, has come under international scrutiny.

Chittagong is an ancient seaport due to its natural harbor. It was noted as one of the largest Eastern ports by the Roman geographer Ptolemy in the 1st century. The harbor has been a gateway through southeastern Bengal in the Indian subcontinent for centuries. Arab sailors and traders, who once explored the Bay of Bengal, set up a mercantile station in the harbor during the 9th century.[8] During the 14th century, the port became a "mint town" of the Sultanate of Bengal, with the status of an administrative center.

During the 16th century, Portuguese historian João de Barros described Chittagong as "the most famous and wealthy city of the Kingdom of Bengal".[9] Portuguese Chittagong was the first European colonial settlement in Bengal. A naval battle in 1666 between the Mughal Empire and Arakan resulted in the expulsion of Portuguese pirates. British colonization began in 1760 when the Nawab of Bengal ceded Chittagong to the East India Company. During World War II, Chittagong was a base for Allied Forces engaged in the Burma Campaign. The port city began to expand and industrialize during the 1940s, particularly after the Partition of British India. During the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, Chittagong was site of the country's declaration of independence.

Chittagong has a high degree of religious and ethnic diversity among Bangladeshi cities, despite having an overwhelming Bengali Muslim majority. Minorities include Bengali Hindus, Bengali Christians, Bengali Buddhists, the Chakmas, the Marmas and the Bohmong.

Etymology

The etymology of Chittagong is uncertain.[10] One explanation credits the first Arab traders for shatt ghangh (Arabic: شط غنغ) where shatt means "delta" and ghangh stood for the Ganges.[10][11][12] The Arakanese chronicle that a king named Tsu-la-taing Tsandaya, after conquering Bengal, set up a stone pillar as a trophy/memorial at the place since called Tst-ta-gaung as the limit of conquest. This Arakanese king ascended the throne in Arakan year 311 corresponding to 952 A.D. He conquered this place two years later. This stone pillar with the inscription Tset-ta-gaung meaning 'to make war is improper' cannot be a myth.[13] Another legend dates the name to the spread of Islam, when a Muslim lit a chati (lamp) at the top of a hill in the city and called out (adhan) for people to come to prayer.[14] However, the local name of the city (in Bengali or Chittagonian) Chatga (Bengali: চাটগা), which is a corruption of Chatgao (Bengali: চাটগাঁও) or Chatigao (Bengali: চাটিগাঁও), and officially Chottogram (Bengali: চট্টগ্রাম) bears the meaning of "village or town of Chatta (possibly a caste or tribe)." Therefore, Bengali name Chattagrama, the Chinese Tsa-ti-kiang, Cheh-ti.gan and the European Chittagong are but the deformed versions of the Arakanese name Tset-ta-gaung.[13]

The port city has been known by various names in history, including Chatigaon, Chatigam, Chattagrama, Islamabad, Chattala, Chaityabhumi and Porto Grande De Bengala. In April 2018, the Bangladesh government decided that the English spelling would change from Chittagong to Chattogram to make the name sound similar to the Bangla spelling.[15]

Name

In 2018, Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina decided to change the city's name to a version of its Bengali spelling without public consultation, drawing protests and concern.[16][17] After that, the name was changed to Chattogram based on its Bengali pronunciation.

History

Stone Age fossils and tools unearthed in the region indicate that Chittagong has been inhabited since Neolithic times.[18] It is an ancient port city, with a recorded history dating back to the 4th century BC.[19] Its harbour was mentioned in Ptolemy's world map in the 2nd century as one of the most impressive ports in the East.[20] The region was part of the ancient Bengali Samatata and Harikela kingdoms. The Candra dynasty once dominated the area, and was followed by the Varman dynasty and Deva dynasty.

Chinese traveler Xuanzang described the area as "a sleeping beauty rising from mist and water" in the 7th century.[21]

Arab Muslim traders frequented Chittagong from the 9th century. In 1154, Al-Idrisi wrote of a busy shipping route between Basra and Chittagong, connecting it with the Abbasid capital of Baghdad.[11]

Many Sufi missionaries settled in Chittagong and played an instrumental role in the spread of Islam.[22]

Sultan Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah of Sonargaon conquered Chittagong in 1340,[23] making it a part of Sultanate of Bengal. It was the principal maritime gateway to the kingdom, which was reputed as one of the wealthiest states in the Indian subcontinent. Medieval Chittagong was a hub for maritime trade with China, Sumatra, the Maldives, Sri Lanka, the Middle East and East Africa. It was notable for its medieval trades in pearls,[24] silk, muslin, rice, bullion, horses and gunpowder. The port was also a major shipbuilding hub.

Ibn Battuta visited the port city in 1345.[25] Niccolò de' Conti, from Venice, also visited around the same time as Battuta.[26] Chinese admiral Zheng He's treasure fleet anchored in Chittagong during imperial missions to the Sultanate of Bengal.[27][28]

Chittagong featured prominently in the military history of the Bengal Sultanate, including during the Reconquest of Arakan and the Bengal Sultanate–Kingdom of Mrauk U War of 1512–1516.

During the 13th and 16th centuries, Arabs and Persians heavily colonized the port city of Chittagong, initially arriving for trade and to preach the word of Islam. Most Arab settlers arrived from the trade route between Iraq and Chittagong, and were perhaps the prime reason for the spread of Islam to Bangladesh.[29] The first Persian settlers have also hinted to arrive for trade and religious purposes, with clues of Persianization tasks as well. Persians and other Iranic peoples have deeply affected the history of the Bengal Sultanate, with Persian being one of the main languages of the Muslim state, as well as also influencing the Chittagonian language and writing scripts.[30][31] It has been affirmed that much of the Muslim population in Chittagong are descendants of the Arab and Persian settlers.[32]

Two decades after Vasco Da Gama's landing in Calicut, the Bengal Sultanate gave permission for the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong to be established in 1528. It became the first European colonial enclave in Bengal. The Bengal Sultanate lost control of Chittagong in 1531 after Arakan declared independence and the established Kingdom of Mrauk U. This altered geopolitical landscape allowed the Portuguese unhindered control of Chittagong for over a century.[33][34]

Portuguese ships from Goa and Malacca began frequenting the port city in the 16th century. The cartaz system was introduced and required all ships in the area to purchase naval trading licenses from the Portuguese settlement.[35] Slave trade and piracy flourished. The nearby island of Sandwip was conquered in 1602. In 1615, the Portuguese Navy defeated a joint Dutch East India Company and Arakanese fleet near the coast of Chittagong.

In 1666, the Mughal government of Bengal led by viceroy Shaista Khan moved to retake Chittagong from Portuguese and Arakanese control. They launched the Mughal conquest of Chittagong. The Mughals attacked the Arakanese from the jungle with a 6,500-strong army, which was further supported by 288 Mughal naval ships blockading the Chittagong harbour.[22] After three days of battle, the Arakanese surrendered. The Mughals expelled the Portuguese from Chittagong. Mughal rule ushered a new era in the history of Chittagong territory to the southern bank of Kashyapnadi (Kaladan river). The port city was renamed as Islamabad. The Grand Trunk Road connected it with North India and Central Asia. Economic growth increased due to an efficient system of land grants for clearing hinterlands for cultivation. The Mughals also contributed to the architecture of the area, including the building of Fort Ander and many mosques. Chittagong was integrated into the prosperous greater Bengali economy, which also included Orissa and Bihar. Shipbuilding swelled under Mughal rule and the Sultan of Turkey had many Ottoman warships built in Chittagong during this period.[28][36]

In 1685, the British East India Company sent out an expedition under Admiral Nicholson with the instructions to seize and fortify Chittagong on behalf of the English; however, the expedition proved abortive. Two years later, the company's Court of Directors decided to make Chittagong the headquarters of their Bengal trade and sent out a fleet of ten or eleven ships to seize it under Captain Heath. However, after reaching Chittagong in early 1689, the fleet found the city too strongly held and abandoned their attempt at capturing it. The city remained under the possession of the Nawab of Bengal until 1793 when East India Company took complete control of the former Mughal province of Bengal.[37][38]

The First Anglo-Burmese War in 1823 threatened the British hold on Chittagong. There were a number of rebellions against British rule, notably during the Indian rebellion of 1857, when the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th companies of the 34th Bengal Infantry Regiment revolted and released all prisoners from the city's jail. In a backlash, the rebels were suppressed by the Sylhet Light Infantry.[11]

Railways were introduced in 1865, beginning with the Eastern Bengal Railway connecting Chittagong to Dacca and Calcutta. The Assam Bengal Railway connected the port city to its interior economic hinterland, which included the world's largest tea and jute producing regions, as well as one of the world's earliest petroleum industries. Chittagong was a major center of trade with British Burma. It hosted many prominent companies of the British Empire, including James Finlay, Duncan Brothers, Burmah Oil, the Indo-Burma Petroleum Company, Lloyd's, Mckenzie and Mckenzie, the Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China, Turner Morrison, James Warren, the Raleigh Brothers, Lever Brothers and the Shell Oil Company.

The Chittagong armoury raid by Bengali revolutionaries in 1930 was a major event in British India's anti-colonial history.

During World War II, Chittagong became a frontline city in the Southeast Asian Theater. It was a critical air, naval and military base for Allied Forces during the Burma Campaign against Japan. The Imperial Japanese Air Force carried out air raids on Chittagong in April and May 1942, in the run up to the aborted Japanese invasion of Bengal.[39][40] British forces were forced to temporarily withdraw to Comilla and the city was evacuated. After the Battle of Imphal, the tide turned in favor of the Allied Forces. Units of the United States Army Air Forces Tenth Air Force were stationed in Chittagong Airfield between 1944 and 1945.[41] American squadrons included the 80th Fighter Group, which flew P-38 Lightning fighters over Burma; the 8th Reconnaissance Group; and the 4th Combat Cargo Group. Commonwealth forces included troops from Britain, India, Australia and New Zealand. The war had major negative impacts on the city, including the growth of refugees and the Great Famine of 1943.[11]

Many wealthy Chittagonians profited from wartime commerce. The Partition of British India in 1947 made Chittagong the chief port of East Pakistan. In the 1950s, Chittagong witnessed increased industrial development. Among pioneering industrial establishments included those of Chittagong Jute Mills, the Burmah Eastern Refinery, the Karnaphuli Paper Mills and Pakistan National Oil. However, East Pakistanis complained of a lack of investment in Chittagong in comparison to Karachi in West Pakistan, even though East Pakistan generated more exports and had a larger population. The Awami League demanded that the country's naval headquarters be shifted from Karachi to Chittagong.[42]

During the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971, Chittagong witnessed heavy fighting between rebel Bengali military regiments and the Pakistan Army. It covered Sector 1 in the Mukti Bahini chain of command. The Bangladeshi Declaration of Independence was broadcast from Kalurghat Radio Station and transmitted internationally through foreign ships in Chittagong Port.[43] Ziaur Rahman and M A Hannan were responsible for announcing the independence declaration from Chittagong on behalf of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The Pakistani military, and supporting Razakar militias, carried out widespread atrocities against civilians in the city. Mukti Bahini naval commandos drowned several Pakistani warships during Operation Jackpot in August 1971.[44] In December 1971, the Bangladesh Air Force and the Indian Air Force carried out heavy bombing of facilities occupied by the Pakistani military. A naval blockade was also enforced.[45]

After the war, the Soviet Navy was tasked with clearing mines in Chittagong Port and restoring its operational capability. 22 vessels of the Soviet Pacific Fleet sailed from Vladivostok to Chittagong in May 1972.[46] The process of clearing mines in the dense water harbour took nearly a year, and claimed the life of one Soviet marine.[47] Chittagong soon regained its status as a major port, with cargo tonnage surpassing pre-war levels in 1973. In free market reforms launched by President Ziaur Rahman in the late 1970s, the city became home to the first export processing zones in Bangladesh. Zia was assassinated during an attempted military coup in Chittagong in 1981. The 1991 Bangladesh cyclone inflicted heavy damage on the city. The Japanese government financed the construction of several heavy industries and an international airport in the 1980s and 90s. Bangladeshi private sector investments increased since 1991, especially with the formation of the Chittagong Stock Exchange in 1995. The port city has been the pivot of Bangladesh's emerging economy in recent years, with the country's rising GDP growth rate.

- The medieval Kadam Mubarak Mosque

Dutch VOC ships in Chittagong, 1702

Dutch VOC ships in Chittagong, 1702 One of the few surviving structures of the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong

One of the few surviving structures of the Portuguese settlement in Chittagong The Chittagong College was established in 1869. A branch of Pubali Bank is also seen in the picture.

The Chittagong College was established in 1869. A branch of Pubali Bank is also seen in the picture. The first steam engine of Bangladesh at the Central Railway Building. Chittagong was the terminus of the Eastern Bengal Railway and the Assam Bengal Railway

The first steam engine of Bangladesh at the Central Railway Building. Chittagong was the terminus of the Eastern Bengal Railway and the Assam Bengal Railway The Chittagong War Cemetery is the burial place of many Allied personnel who died during the Burma Campaign of World War II

The Chittagong War Cemetery is the burial place of many Allied personnel who died during the Burma Campaign of World War II Port of Chittagong in 1960

Port of Chittagong in 1960 Royal Air Force Thunderbolt Mark Is of No. 135 Squadron RAF, lined up at Chittagong in 1944

Royal Air Force Thunderbolt Mark Is of No. 135 Squadron RAF, lined up at Chittagong in 1944

Geography

Topography

.jpg)

Chittagong lies at 22°20′06″N 91°49′57″E. It straddles the coastal foothills of the Chittagong Hill Tracts in southeastern Bangladesh. The Karnaphuli River runs along the southern banks of the city, including its central business district. The river enters the Bay of Bengal in an estuary located 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) west of downtown Chittagong. Mount Sitakunda is the highest peak in Chittagong District, with an elevation of 351 metres (1,152 ft).[48] Within the city itself, the highest peak is Batali Hill at 85.3 metres (280 ft). Chittagong has many lakes that were created under Mughal rule. In 1924, an engineering team of the Assam Bengal Railway established the Foy's Lake.[48]

Ecological hinterland

The Chittagong Division is known for its rich biodiversity. Over 2000 of Bangladesh's 6000 flowering plants grow in the region.[49] Its hills and jungles are laden with waterfalls, fast flowing river streams and elephant reserves. St. Martin's Island, within the Chittagong Division, is the only coral island in the country. The fishing port of Cox's Bazar is home to one of the world's longest natural beaches. In the east, there are the three hill districts of Bandarban, Rangamati, and Khagrachari, home to the highest mountains in Bangladesh. The region has numerous protected areas, including the Teknaf Game Reserve and the Sitakunda Botanical Garden and Eco Park.[50]

Patenga beach in the main seafront of Chittagong, located 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) west of the city.

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Chittagong has a tropical monsoon climate (Am).[51]

Chittagong is vulnerable to North Indian Ocean tropical cyclones. The deadliest tropical cyclone to strike Chittagong was the 1991 Bangladesh cyclone, which killed 138,000 people and left as many as 10 million homeless.[52]

| Climate data for Chittagong (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.7 (89.1) |

33.9 (93.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

36.7 (98.1) |

36.7 (98.1) |

34.4 (93.9) |

33.9 (93.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

34.4 (93.9) |

34.9 (94.8) |

31.1 (88.0) |

38.9 (102.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 26.0 (78.8) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.8 (87.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.8 (89.2) |

31.7 (89.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

27.2 (81.0) |

30.4 (86.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

25.7 (78.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.1 (82.6) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.7 (81.9) |

24.9 (76.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

25.9 (78.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 14.0 (57.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

21.7 (71.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.2 (50.4) |

13.6 (56.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

19.4 (66.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

17.2 (63.0) |

12.7 (54.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.5 (45.5) |

5.2 (41.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 7.3 (0.29) |

25.0 (0.98) |

55.5 (2.19) |

136.4 (5.37) |

314.0 (12.36) |

591.3 (23.28) |

735.6 (28.96) |

513.9 (20.23) |

239.3 (9.42) |

197.8 (7.79) |

59.5 (2.34) |

14.1 (0.56) |

2,889.7 (113.77) |

| Average precipitation days | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 13 | 16 | 19 | 17 | 13 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 104 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73 | 70 | 74 | 77 | 79 | 83 | 85 | 85 | 83 | 81 | 78 | 75 | 79 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 264.1 | 244.3 | 276.4 | 242.7 | 227.2 | 116.7 | 105.1 | 124.4 | 166.7 | 218.2 | 241.3 | 245.5 | 2,472.6 |

| Source 1: Bangladesh Meteorological Department[53][54][55] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Sistema de Clasificación Bioclimática Mundial (extremes),[56] Deutscher Wetterdienst (sun, 1961–1990)[57][lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

Government

The Chittagong City Corporation (CCC) is responsible for governing municipal areas in the Chittagong Metropolitan Area. It is headed by the Mayor of Chittagong. The mayor and ward councillors are elected every five years. The mayor is Awami League leader A. J. M. Nasiuruddin, as of May 2015.[58] The city corporation's mandate is limited to basic civic services, however, the CCC is credited for keeping Chittagong one of the cleaner and most eco-friendly cities in Bangladesh.[59][60] Its principal sources of revenue are municipal taxes and conservancy charges.[11] The Chittagong Development Authority is responsible for implementing the city's urban planning.

The Deputy Commissioner and District Magistrate are the chiefs of local administration as part of the Government of Bangladesh. Law enforcement is provided by the Chittagong Metropolitan Police and the Rapid Action Battalion-7. The District and Sessions Judge is the head of the local judiciary on behalf of the Supreme Court of Bangladesh.[11] The Divisional Special Judge's Court is located in the colonial-era Chittagong Court Building.

Military

Chittagong is a strategically important military port on the Bay of Bengal. The Chittagong Naval Area is the principal base of the Bangladesh Navy and the home port of most Bangladeshi warships.[61] The Bangladesh Naval Academy and the navy's elite special force- Special Warfare Diving and Salvage (SWADS) are also based in the city.[62] The Bangladesh Army's 24th Infantry Division is based in Chittagong Cantonment, and the Bangladesh Air Force maintains the BAF Zahurul Haq Air Base in Chittagong.[63] The city is also home to the Bangladesh Military Academy, the premier training institute for the country's armed forces.

Diplomatic representation

In the 1860s, the American Consulate-General in the Bengal Presidency included a consular agency in Chittagong.[64] Today, Chittagong hosts an assistant high commission of India and a consulate general of Russia. The city also has honorary consulates of Turkey, Japan, Germany, South Korea, Malaysia, Italy, and the Philippines.[65][66][67][68][69][70][71]

Economy

| Top publicly traded companies in Chittagong, in 2014[72] | |||||

| Jamuna Oil Company | |||||

| BSRM | |||||

| Padma Oil Company | |||||

| PHP | |||||

| Meghna Petroleum | |||||

| GPH Ispat | |||||

| Aramit Cement | |||||

| Western Marine Shipyard | |||||

| RSRM | |||||

| Hakkani Pulp & Paper | |||||

| Source: Chittagong Stock Exchange | |||||

.jpg)

A substantial share of Bangladesh's national GDP is attributed to Chittagong. The City generated approximately $25.5 billion in nominal (2014)[73] and US$67.26 billion in PPP terms converted from nominal GDP of $25.5 Billion dollars with a nominal vs. PPP factor of 2.638.[74] contributing around 12%[73] of the nation's economy. Chittagong generates for 40% of Bangladesh's industrial output, 80% of its international trade and 50% of its governmental revenue.[75][76] The Chittagong Stock Exchange has more than 700 listed companies, with a market capitalisation of US$32 billion in June 2015.[72] The city is home to many of the country's oldest and largest corporations. The Port of Chittagong handled US$60 billion in annual trade in 2011, ranking 3rd in South Asia after the Port of Mumbai and the Port of Colombo.[7][76]

The Agrabad area is the main central business district of the city. Major Bangladeshi conglomerates headquartered in Chittagong include M. M. Ispahani Limited, BSRM, A K Khan & Company, PHP Group, James Finlay Bangladesh, the Habib Group, the S. Alam Group of Industries, KDS Group and the T. K. Group of Industries. Major state-owned firms headquartered there include Pragati Industries, the Jamuna Oil Company, the Bangladesh Shipping Corporation and the Padma Oil Company. The Chittagong Export Processing Zone was ranked by the UK-based magazine, Foreign Direct Investment, as one of the leading special economic zones in the world, in 2010.[77] Other SEZs include the Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone and Korean EPZ. The city's key industrial sectors include petroleum, steel, shipbuilding, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, textiles, jute, leather goods, vegetable oil refineries, glass manufacturing, electronics and motor vehicles. The Chittagong Tea Auction sets the price of Bangladesh Tea. The Eastern Refinery is Bangladesh's largest oil refinery. GlaxoSmithKline has had operations in Chittagong since 1967.[78] Western Marine Shipyard is a leading Bangladeshi shipbuilder and exporter of medium-sized ocean going vessels. In 2011–12, Chittagong exported approximately US$4.5 billion in ready-made garments.[79] The Karnaphuli Paper Mills were established in 1953.

International banks operating in Chittagong include HSBC, Standard Chartered and Citibank NA. Chittagong is often called Bangladesh's commercial capital due to its diversified industrial base and seaport. The port city has ambitions to develop as a global financial centre and regional transshipment hub, given its proximity to North East India, Burma, Nepal, Bhutan and Southwest China.[80][81]

Culture

.jpg)

An inhabitant of Chittagong is called Chittagonian in English.[82] For centuries, the port city has been a melting pot for people from all over the world. Its historic trade networks have left a lasting impact on its language, culture and cuisine. The Chittagonian language has many Arabic, Persian, English and Portuguese loanwords.[11] The immensely popular traditional feast of Mezban features the serving of hot beef dish with white rice.[82] The cultivation of pink pearls is a historic activity in Chittagong. Its Mughal-era name, Islamabad (City of Islam), continues to be used in the old city. The name was given due to the port city's history as a gateway for early Islamic missionaries in Bengal. Notable Islamic architecture in Chittagong can be seen in the historic Bengal Sultanate-era Hammadyar Mosque and the Mughal fort of Anderkilla. Chittagong is known as the Land of the Twelve Saints[83] due to the prevalence of major Sufi Muslim shrines in the district. Historically, Sufism played an important role in the spread of Islam in the region. Prominent dargahs include the mausoleum of Shah Amanat and the shrine of Bayazid Bastami. The Bastami shrine hosts a pond of black softshell turtles.

During the medieval period, many poets thrived in the region when it was part of the Bengal Sultanate and the Kingdom of Mrauk U. Under the patronage of Sultan Alauddin Husain Shah's governor in Chittagong, Kabindra Parameshvar wrote his Pandabbijay, a Bengali adaptation of the Mahabharata.[84] Daulat Qazi lived in the region during the 17th century reign of the Kingdom of Mrauk U. Chittagong is home to several important Hindu temples, including the Chandranath Temple on the outskirts of the city, which is dedicated to the Hindu goddess Sita.[85] The city also hosts the country's largest Buddhist monastery and council of monks. The Roman Catholic Diocese of Chittagong is the oldest catholic mission in Bengal.[86]

Major cultural organisations in the city include the Theatre Institute Chittagong and the Chittagong Performing Arts Academy. The city has a vibrant contemporary art scene.

Being home to the pioneering rock bands in the country like Souls[87] and LRB,[88] Chittagong is regarded as the "birthplace of Bangladeshi rock music".[89][90][91]

Demographics

Chittagong has a population of more than 2.5 million,[3] and its Metropolitan Area has a population of 4,009,423.[92] By gender, the population was 54.36% male and 45.64% female, and the literacy rate in the city was 60 percent, in 2002.[93] Muslims at 86% form the overwhelming majority of the population and rest being 12% Hindus and 2% other religions.[11]

Chittagong was a melting pot of ethnicities during the Bengal Sultanate and Mughal Bengal periods. Muslim immigration started as early as seventh century, and significant Muslim settlements occurred during medieval period. Muslim traders, rulers and preachers from Persia and Arabs were the early Muslim settlers, and descendants of them are the majority of current Muslim population of the city. The city has a relatively wealthy and economically influential Shia Muslim community, including Ismailis and Twelver Shias. The city also has many ethnic minorities, especially members of indigenous groups from the frontier hills of Chittagong Division, including Chakmas, Rakhines and Tripuris; as well as Rohingya refugees. The Bengali-speaking Theravada Buddhists of the area, known as Baruas, are one of the oldest communities in Chittagong and one of the last remnants of Buddhism in Bangladesh.[94][95][96][97] Descendants of Portuguese settlers, often known as Firingis, also live in Chittagong, as well as Catholics, who largely live in the old Portuguese enclave of Paterghatta.[11] There is also a small Urdu-speaking Bihari community living in the ethnic enclave known as Bihari Colony.[98][99]

Like other major urban centres in South Asia, Chittagong has experienced a steady growth in its slum settlements as a result of the increasing economic activities in the city and emigration from rural areas. According to a poverty reduction publication of the International Monetary Fund, there were 1,814 slums within the city corporation area, inhabited by about 1.8 million slum dwellers, the second highest in the country after the capital, Dhaka.[100] The slum dwellers often face eviction by the local authorities, charging them with illegal abode on government lands.[101][102]

Media and communications

There are various newspapers, including daily newspapers, opposition newspapers and business newspapers, based in Chittagong. Daily newspapers include Dainik Azadi,[104] Peoples View,[105] The Daily Suprobhat Bangladesh, Purbokon, Life, Karnafuli, Jyoti, Rashtrobarta and Azan. Furthermore, there are a number of weekly and monthly newspapers. These include weeklies such as Chattala, Jyoti, Sultan, Chattagram Darpan and the monthlies such as Sanshodhani, Purobi, Mukulika and Simanto. The only press council in Chittagong is the Chittagong Press Club. Government owned Bangladesh Television and Bangladesh Betar have transmission centres in Chittagong. A local online news & media Channel based on the local dialect language "Chatgaya" was launched in 2016 called CplusTv,[106] gained vast popularity. The channel is YouTube- and social network-based, and it reached the 1 million followers milestone on Facebook.

Chittagong has been featured in all aspects of Bangladeshi popular culture, including television, movies, journals, music and books. Nearly all televisions and radios in Bangladesh have coverage in Chittagong. Renowned Bollywood film director Ashutosh Gowariker directed a movie based on the 1930s Chittagong Uprising, Movie's name is Khelein Hum Jee Jaan Sey[107] in which Abhishek Bachchan played the lead role.[108][109]

Utilities

The southern zone of the Bangladesh Power Development Board is responsible for supplying electricity to city dwellers.[110][111] The fire services are provided by the Bangladesh Fire Service & Civil Defence department, under the Ministry of Home Affairs.[112]

The water supply and sewage systems are managed by the Chittagong Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (Chittagong WASA).[113][114] Water is primarily drawn from Karnaphuli River and then purified in the Mohra Purification Plant.[115]

Chittagong has extensive GSM and CDMA coverage, served by all the major mobile operators of the country, including Grameenphone, Banglalink, Citycell, Robi, TeleTalk and Airtel Bangladesh. However, landline telephone services are provided through the state-owned Bangladesh Telegraph and Telephone Board (BTTB), as well as some private operators. BTTB also provides broadband Internet services, along with some private ISPs, including the 4G service providers Banglalion[116] and Qubee.[117]

Education

The education system of Chittagong is similar to that of rest of Bangladesh, with four main forms of schooling. The general education system, conveyed in both Bangla and English versions, follows the curriculum prepared by the National Curriculum and Textbook Board, part of the Ministry of Education.[118] Students are required to take four major board examinations: the Primary School Certificate (PSC), the Junior School Certificate (JSC), the Secondary School Certificate (SSC) and the Higher Secondary School Certificate (HSC) before moving onto higher education. The Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Chittagong is responsible for administering SSC and HSC examinations within the city.[119][120] The Madrasah education system is primarily based on Islamic studies, though other subjects are also taught. Students are prepared according to the Dakhil and Alim examinations, which are controlled by the Bangladesh Madrasah Education Board and are equivalent to SSC and HSC examinations of the general education system respectively.[121] There are also several private schools in the city, usually referred to as English medium schools,[118] which follow the General Certificate of Education.

The British Council supervises the O Levels and A levels examinations, conducted twice a year, through the Cambridge International and Edexcel examination boards.[122][123] The Technical and Vocational education system is governed by the Directorate of Technical Education (DTE) and follow the curriculum prepared by Bangladesh Technical Education Board (BTEB).[124][125] Chittagong College, established in 1869, is the earliest modern institution for higher education in the city.[126] Chittagong Veterinary and Animal Sciences University is the only public university located in Chittagong city. Chittagong Medical College is the only government medical college in Chittagong.

University of Chittagong is located 22 kilometres (14 miles) north and Chittagong University of Engineering and Technology is located 25 kilometres (16 miles) north of the Chittagong city. University of Chittagong, which was established in 1966 is one of the largest universities in Bangladesh. Chittagong University of Engineering and Technology, established in 1968, is one of the five public engineering universities in Bangladesh and the only such university in the Chittagong Division.

The city also hosts several other private universities and medical colleges. The BGC Trust University Bangladesh, Chittagong Independent University (CIU), Asian University for Women, Port City International University, East Delta University, International Islamic University, Premier University, Southern University, University of Information Technology and Sciences and the University of Science & Technology Chittagong are among them. Chittagong has public, denominational and independent schools. Public schools, including pre-schools, primary and secondary schools and special schools are administered by the Ministry of Education and Chittagong Education Board. Chittagong has governmental and non-governmental primary schools, international schools and English medium schools.

Health

The Chittagong Medical College Hospital is the largest state-owned hospital in Chittagong. The Chittagong General Hospital, established in 1901, is the oldest hospital in the city.[127] The Bangladesh Institute of Tropical and Infectious Diseases (BITID) is based the city. Other government-run medical centres in the city include the Family Welfare Centre, TB Hospital, Infectious Disease Hospital, Diabetic Hospital, Mother and Children Hospital and the Police Hospital. Among the city's private hospitals are the Chittagong Metropolitan Hospital, Surgiscope Hospital, CSCR, Centre Point Hospital, National Hospital and Mount Hospital Ltd.[128][129][130]

Transport

Transport in Chittagong is similar to that of the capital, Dhaka. Large avenues and roads are present throughout the metropolis. There are various bus systems and taxi services, as well as smaller 'baby' or 'CNG' taxis, which are tricycle-structured motor vehicles. Foreign and local ridesharing companies like Uber and Pathao are operating in the city.[131] There are also traditional manual rickshaws, which are very common.

Road

As the population of the city has begun to grow extensively, the Chittagong Development Authority (CDA) has undertaken some transportation initiatives aimed at easing the traffic congestion in Chittagong. Under this plan, the CDA, along with the Chittagong City Corporation, have constructed some flyovers and expanded the existing roads within the city. There are also some other major expressways and flyovers under-construction, most notably the Chittagong City Outer Ring Road, which runs along the coast of Chittagong city. This ring road includes a marine drive along with five feeder roads, and is also meant to strengthen the embankment of the coast.[132][133][134][135][136] The government has also began the construction of a 9.3 kilometres (5.8 mi) underwater expressway tunnel through the Karnaphuli river to ensure better connectivity between the northern and southern parts of Chittagong. This tunnel will be the first of its kind in South Asia.[137][138][139]

The N1 (Dhaka-Chittagong Highway), a major arterial national highway, is the only way to access the city by motor vehicle from most other part of the country. It is considered a very busy and dangerous highway. This highway is also part of AH41 route of the Asian Highway Network. It has been upgraded to 4 lanes.[140] The N106 (Chittagong-Rangamati Highway) is another important national highway that connects the Chittagong Hill Tracts with the city.

Rail

Chittagong can also be accessed by rail. It has a station on the metre gauge, eastern section of the Bangladesh Railway, whose headquarters are also located within the city. There are two main railway stations, on Station Road and in the Pahartali Thana. Trains to Dhaka, Sylhet, Comilla, and Bhairab are available from Chittagong. The Chittagong Circular Railway was introduced in 2013 to ease traffic congestion and to ensure better public transport service to the commuters within the city. The railway includes high-speed DEMU trains each with a carrying capacity of 300 passengers. These DEMU trains also travel on the Chittagong-Laksham route which connects the city with Comilla.[141][142]

Air

The Shah Amanat International Airport (IATA: CGP, ICAO: VGEG), located at South Patenga, serves as Chittagong's only airport. It is the second busiest airport in Bangladesh. The airport is capable of annually handling 1.5 million passengers and 6,000 tonnes of cargo.[143] Known as Chittagong Airfield during World War II, the airport was used as a combat airfield, as well as a supply point and photographic reconnaissance base by the United States Army Air Forces Tenth Air Force during the Burma Campaign 1944–45.[41] It officially became a Bangladeshi airport in 1972 after Bangladesh's liberation war.[144] International services fly to major cities of the Arabian Peninsula as well as to Indian cities of Kolkata and Chennai.[145] At present, Middle Eastern low-cost carriers like Air Arabia, Flydubai and SalamAir operate flights from the city to these destinations along with airlines of Bangladesh.[145] All Bangladeshi airlines operate regular domestic flights to Dhaka. The airport was formerly known as MA Hannan International Airport, but was renamed on 2 April 2005 by the Government of Bangladesh.

Sports

Chittagong has produced numerous cricketers, footballers and athletes, who have performed at the national level. Tamim Iqbal, Akram Khan, Minhajul Abedin, Aftab Ahmed, Nafees Iqbal, Nazimuddin, Faisal Hossain, Tareq Aziz, Mominul Haque, Irfan Sukkur, Yasir Ali Chowdhury, Nayeem Hasan, Minhajul Abedin Afridi are some of the most prominent figures among them. Cricket is the most popular sport in Chittagong, while football, tennis and kabaddi are also popular. A number of stadiums are located in Chittagong with the main one being the multipurpose MA Aziz Stadium, which has a seating capacity of 20,000 and hosts football matches in addition to cricket.[146] MA Aziz Stadium was the stadium where Bangladesh achieved its first ever Test cricket victory, against Zimbabwe in 2005.[147] The stadium now focuses only on football, and is currently the main football venue of the city. Zohur Ahmed Chowdhury Stadium, is currently the main cricket venue of the city, which was awarded Test status in 2006, hosting both domestic and international cricket matches. The city hosted two group matches of the 2011 ICC Cricket World Cup, both taking place in Zohur Ahmed Chowdhury Stadium.[148] It also co-hosted 2014 ICC World Twenty20 along with Dhaka and Sylhet, Zohur Ahmed Chowdhury Stadium hosted 15 group stage matches. Other stadiums in Chittagong include the Women's Complex Ground. Major sporting clubs such as, Mohammedan Sporting Club and Abahani Chittagong are also located in the city. Chittagong is also home to the Bangladesh Premier League franchise, the Chittagong Vikings.

Twin towns and sister cities

Chittagong is twinned with:

See also

Notes

Explanatory notes

- Station ID for Chittagong (Patenga) is 41978 Use this station ID to locate the sunshine duration

Citations

- "History of Chittagong City Corporation". Chittagong City Corporation. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- "Area, Population and Literacy Rate by Paurashava –2001" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- "Population & Housing Census-2011: Union Statistics" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. p. 39. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- "Economics Landscape of Chittagong". chittagongchamber.com. Chittagong Chamber. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Mahadi Al Hasnat (2 April 2018). "Mixed reactions as govt changes English spellings of 5 district names". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places - Google Books". Books.google.com.bd. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- "Pangaon container terminal to get a boost". The Daily Star. 3 January 2016.

- "Arabs, the - Banglapedia".

- "Chittagong | Bangladesh".

- O'Malley, L.S.S. (1908). Chittagong. Eastern Bengal District Gazetteers. 11A. Calcutta: The Bengal Secretariat Book Depot. p. 1. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Osmany, Shireen Hasan (2012). "Chittagong City". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Bernoulli, Jean; Rennell, James; Anquetil-Duperron, M.; Tieffenthaller, Joseph (1786). Description historique et géographique de l'Inde (in French). 2. Berlin: C. S. Spener. p. 408. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Quanungo, Suniti Bhushan (1988). A History of Chittagong. 1. Chittagong: Dipanka Quanungol Billan Printers. p. 17.

- "The Asian University for Women". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 9 February 2005. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- "Bangladesh changes English spellings of five districts".

- "Mixed reactions as govt changes English spellings of 5 district names". 2 April 2018.

- "Experts warn of trade hits from renaming Chittagong".

- "Bangladesh towards 21st century". google.co.uk. 1994.

- "Custom House Chittagong". Archived from the original on 9 November 2015.

- Mannan, Abdul (1 April 2012). "Chittagong – looking for a better future". New Age. Dhaka. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013.

- "Past of Ctg holds hope for economy". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- Trudy, Ring; M. Salkin, Robert; La Boda, Sharon; Edited by Trudy Ring (1996). International dictionary of historic places. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1-884964-04-4. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- "District LGED". lged.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Donkin, R. A. (1998). Beyond Price. google.com. ISBN 9780871692245.

- Dunn, Ross E. (1986). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05771-5.

- Ray, Aniruddha (2012). "Conti, Nicolo de". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Sen, Dineshchandra (1988). The Ballads of Bengal. Mittal Publications. pp. xxxiii.

- Eaton, Richard Maxwell (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. pp. 234, 235. ISBN 0-520-20507-3.

- "Arabs, The - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org.

- "The Role of the Persian Language in Bengali and the World Civilization: An Analytical Study" (PDF). www.uits.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- Eaton, Richard M. (1994). The rise of Islam and the Bengal frontier, 1204-1760. Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195635867.

- "Bangladesh - Ethnic groups". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Navarro-Tejero, Antonia; Gupta, Taniya (2014). "Chapter Two". India in Canada : Canada in India. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-5571-6.

- Dasgupta, Biplab (2005). European trade and colonial conquest. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 1-84331-029-5.

- Pearson, M.N. (2006). The Portuguese in India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-02850-7.

- Chittagong, Asia and Oceania:International Dictionary of Historic Places

- Osmany, Shireen Hasan; Mazid, Muhammad Abdul (2012). "Chittagong Port". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Hunter, William Wilson (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 308, 309.

- "Nippon Bombers Raid Chittagong". The Miami News. Associated Press. 9 May 1942.

- "Japanese Raid Chittagong: Stung By Allied Bombing". The Sydney Morning Herald. 14 December 1942. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Maurer, Maurer. Air Force Combat Units of World War II. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Office of Air Force History, 1983. ISBN 0-89201-092-4

- Mannan, Abdul (25 June 2011). "Rediscovering Chittagong - the gateway to Bangladesh". Daily Sun (Editorial). Dhaka. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014.

- "Operation Jackpot - Banglapedia".

- Administrator. "Muktijuddho (Bangladesh Liberation War 1971) part 37 - Bangladesh Biman Bahini (Bangladesh Air Force or BAF) - History of Bangladesh". Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- Rao, K. V. Krishna (1991). Prepare Or Perish: A Study of National Security. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 9788172120016 – via Google Books.

- "In the Spirit of Brotherly Love". The Daily Star. 29 May 2014.

- "Rescue Operation on Demining and Clearing of Water Area of Bangladesh Seaports 1972-74". Consulate General of the Russian Federation in Chittagong. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "About Chittagong". muhammadyunus.org. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 6 June 2015.

- "Flora and Fauna - Bangladesh high commission in India". bdhcdelhi.org. Archived from the original on 20 August 2013.

- "Protected Areas". bforest.gov.bd. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013.

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson, B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606.

- "NOAA's Top Global Weather, Water and Climate Events of the 20th Century" (PDF). NOAA Backgrounder. 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

- "Climate of Bangladesh" (PDF). Bangladesh Meteorological Department. pp. 19–23. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Normal Monthly Rainy Day" (PDF). Bangladesh Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Normal Monthly Humidity" (PDF). Bangladesh Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 24 December 2018.

- "Bangladesh - Chittagong" (in Spanish). Centro de Investigaciones Fitosociológicas. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- "Station 41978 Chittagong (Patenga)". Global station data 1961–1990—Sunshine Duration. Deutscher Wetterdienst. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- "CCC mayor Nasir vows to fulfil pre-election pledges". The Daily Sun. Dhaka. 10 May 2015.

- Karim, A.K.M. Rezaul (2006). "Best Practice: A Perspective of 'Clean and Green' Chittagong" (PDF). The First 2006 Workshop Population and Environmental Protection in Urban Planning. Kobe, Japan: Asian Urban Information Centre of Kobe.

- Roberts, Brian; Kanaley, Trevor, eds. (2006). Urbanization and Sustainability in Asia: Case Studies of Good Practice. Asian Development Bank. p. 58. ISBN 978-971-561-607-2.

- Raihan Islam. "CCNA :: Chittagong Naval Area". ccna.mil.bd. Archived from the original on 6 June 2015.

- "Special Warfare Diving and Salvage (SWADS)". ShadowSpear. 22 August 2010.

- "PM awards National Standard to BAF Base Zahurul Haque". newagebd.net.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110701063403/http://span.state.gov/wwwfspjulyaug072.pdf

- http://dhaka.emb.mfa.gov.tr/Mission/About

- https://www.jica.go.jp/bangladesh/english/office/topics/speech181107.html

- https://dhaka.diplo.de/bd-en/botschaft/honorarkonsuln/-/1900526

- http://overseas.mofa.go.kr/bd-en/brd/m_2128/view.do?seq=740737&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&multi_itm_seq=0&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&company_cd=&company_nm=&page=2

- https://www.kln.gov.my/web/bgd_dhaka/honorary_consul

- https://ambdhaka.esteri.it/ambasciata_dhaka/en/ambasciata/la_rete_consolare/la-rete-consolare.html

- https://www.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/trade/philippines-opens-visa-centre-in-ctg-1549876615

- "Chittagong Stock Exchange". Chittagong Stock Exchange Limited.

- "Economics Landscape of Chittagong". chittagongchamber.com. Chittagong Chamber. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- "GDP (nominal) vs GDP (PPP)". statisticstimes.com. 4 August 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "Lack of requisite infrastructure". The Daily Star. 9 April 2012.

- Ethirajan, Anbarasan (4 September 2012). "Bangladesh pins hope on Chittagong port". BBC News.

- "Ctg EPZ 4th in global ranking". The Daily Star.

- "GSK looks to fortify its Bangladesh presence". The Daily Star.

- "Ctg's share in garment exports on the decline". The Daily Star.

- "The region is Ctg's oyster". The Daily Star.

- Shariful. "Growing Up With Two Giants". muhammadyunus.org.

- "MAJESTIC MEZBAN". 10 October 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Harder, Hans (2011). Sufism and Saint Veneration in Contemporary Bangladesh: The Maijbhandaris of Chittagong. Routledge. ISBN 9781136831898.

- Sen, Sukumar (1991, reprint 2007). Bangala Sahityer Itihas, Vol.I, (in Bengali), Kolkata: Ananda Publishers, ISBN 81-7066-966-9, pp. 208–11

- "Of Shiva Chaturdashi and Sitakunda". The Daily Star. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "Chronicle/Snippets | ctgdiocese.com". www.ctgdiocese.com. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- "Bangladesh band SOULS: The idea of co-existence is central to our music". Times of India. 11 December 2012. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- Imran, Nadee Naboneeta (11 October 2012). "Ayub Bachchu The rock guru". New Age. Archived from the original on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- "Concert: 'Rise of Chittagong Kaos'". The Independent. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- "Warfaze and Nemesis perform Friday in Ctg". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- "Rocking concert: Rise of Chittagong Kaos". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- "Bangladesh: Districts and Cities". citypopulation.de.

- "Economics Landscape of Chittagong". The Chittagong Chamber of Commerce & Industry. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- Ahmed, Ar. Sayed (2013). "An imagination of Bikrampur Buddhist Vihara from the foot-print of Atish Dipankar's travel" (PDF). American Journal of Engineering Research. 2 (12).

- Chakma, Niru Kumar (2012). "Buddhism". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Singh, N. K. (2008). Contemporary Indian Buddhism: Tradition and Transformation. p. 16. ISBN 9788182202474.

- Hattaway, Paul (2004). Peoples of the Buddhist World:A Christian Prayer Diary. p. 9. ISBN 9780878083619.

- "Motif artisans in Ctg race against time as Eid nears". The Daily Star. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Bihari colony buzzes with Eid activities". Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- International Monetary Fund. Asia and Pacific Dept (2013). Bangladesh: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper. IMF. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-4755-4352-0.

- "Slum-dwellers living in fear of eviction". Daily Sun. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- "Illegal structures close in on Ctg railway". New Age. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- Population and Housing Census 2011 - Volume 3: Urban Area Report (PDF), Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, August 2014

- DainikAzadi.net, Daily Azadi official website

- Peoples-View.org, Peoples-View official website

- Cplustv, Cplustv Wikipedia Site

- "Gowariker's next based on Chittagong Uprising". AbhishekBachchan.org. Archived from the original on 4 July 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- "Gowarikar launches new film venture". BBC Shropshire. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- "My movies are about books that influence me: Ashutosh Gowariker". Mid Day. Mumbai. Indo-Asian News Service (IANS). 9 October 2009. Retrieved 22 December 2009.

- "PDB Ctg". Bangladesh Power Development Board. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Electricity". National Web Portal of Bangladesh. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ফায়ার সার্ভিস ও সিভিল ডিফেন্স অধিদপ্তর [Fire Service and Civil Defence Department]. Bangladesh Fire Service & Civil Defence (in Bengali). Archived from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "$170m World Bank support to improve Ctg water supply". The News Today. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- "Second Karnaphuli water supply project launched". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- Rahman, Md Moksedur (2012). "WASA Chittagong". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Coverage Map". Banglalion. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- "Coverage". Qubee. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- Mokhduma, Tabassum. "Profile of Some Schools in Chittagong". The Daily Star. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- "Activities". Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, Chittagong. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- "Primary completion exams duration increased". New Age. Dhaka. 5 August 2013. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013.

- "Activities of Board". Bangladesh Madrasah Education Board. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- "O-Level Exams". British Council. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- "A-level exams". British Council. Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- "Functions of DTE". Directorate of Technical Education. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- "Activities". Bangladesh Technical Education Board. Archived from the original on 4 August 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Ullah Khan, Sadat (2012). "Chittagong College". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Chittagong General Hospital needs care". thedailystar.net. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015.

- "Quality healthcare needed to make Chittagong global city". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- "Ctg General Hospital turns into 250-bed institution". Daily Sun. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- "JICA to support CCC dev projects". The Financial Express. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- "Transforming ride-sharing into sustainable business". The Daily Star. Dhaka. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- "CDA's mega project of outer ring road". The Financial Express. Dhaka. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "Chittagong City Outer Ring Road project". Chittagong Development Authority. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "Plethora of CDA projects, port city to see dev not found in last 50 yrs". The Financial Express. Dhaka. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "Primary alignment design of Tk 100b Ctg Marine Drive prepare d". The Financial Express. Dhaka. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "Construction of flyover, marine drive this year". The Daily Star. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "First ever river tunnel under Karnaphuli planned". The Financial Express. Dhaka. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- "Work on Karnaphuli tunnel to begin this FY: Minister". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "Karnaphuli tunnel construction to start this fiscal". The Daily Star. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- "Part of 4-lane highway to be ready by June". The Daily Star.

- "DEMU trains begin debut run in Ctg". Bdnews24.com. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- "Commuter trains hit tracks in Ctg". The Daily Star. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- "SAIA needs proper facilities to harness it's [sic] potential & to get out of trouble". Bangladesh Monitor. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- "Chittagong Airport Development Project". Civil Aviation Authority of Bangladesh. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- "Chittagong Shah Amanat International Airport Departures". Flightradar24. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "MA Aziz Stadium". Cricinfo.com. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- "MA Aziz Stadium Chittagong". Warofcricket.com. Archived from the original on 13 February 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- "Zohur Ahmed Chowdhury Stadium, Chittagong". Warofcricket.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 2009-12-20.

- "Sister Cities of Chittagong". Sistercities.info. 4 July 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chittagong. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Chittagong. |

- Official Web Portal of Chittagong

- Chittagong City Corporation

- Chittagong Development Authority

- Chittagong Metropolitan Police

.jpg)

.jpg)