Arunachal Pradesh

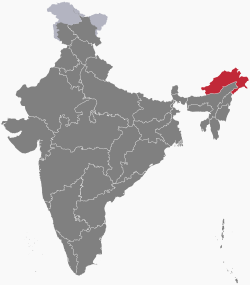

Arunachal Pradesh (/ˌɑːrəˌnɑːtʃəl prəˈdɛʃ/, literally "land of dawn-lit mountains")[11] is the northeasternmost state of India. It borders the states of Assam and Nagaland to the south. It shares international borders with Bhutan in the west, Myanmar in the east, and a disputed border with China in the north at the McMahon Line. Itanagar is the state capital of Arunachal Pradesh. Arunachal Pradesh is the largest of the Seven Sister States of Northeast India by area.

Arunachal Pradesh | |

|---|---|

.jpg) .jpg)   | |

| Etymology: Arunachal (meaning 'dawn-lit mountains') and Pradesh (meaning 'province or territory') | |

| |

| Coordinates (Itanagar): 27.06°N 93.37°E | |

| Country | India |

| Union territory | 21 January 1972 |

| State | 20 February 1987[1] |

| Capital | Itanagar |

| Largest city | Itanagar |

| Districts | 25 |

| Government | |

| • Body | Government of Arunachal Pradesh |

| • Governor | B. D. Mishra[2] |

| • Chief Minister | Pema Khandu[3](BJP)[4] |

| • Legislature | Unicameral (60 seats) |

| • Parliamentary constituency | Rajya Sabha 1 Lok Sabha 2 |

| • High Court | Guwahati High Court - Itanagar Bench |

| Area | |

| • Total | 83,743 km2 (32,333 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 14th |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 1,382,611 |

| • Rank | 27th |

| • Density | 17/km2 (43/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+05:30 (IST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IN-AR |

| HDI | |

| HDI rank | 18th (2005) |

| Literacy | 66.95% |

| Official languages |

|

| Website | arunachalpradesh |

| Symbols | |

| Mammal | Gayal[6][7][8] |

| Bird | Hornbill[6][7][8] |

| Flower | Foxtail orchid[6][7][8] |

| Tree | Hollong[9][10] |

As of the 2011 Census of India, Arunachal Pradesh has a population of 1,382,611 and an area of 83,743 square kilometres (32,333 sq mi). It is an ethnically diverse state, with predominantly Monpa people in the west, Tani people in the center, Tai people in the east, and Naga people in the south of the state.

A major part of the state is claimed by both the People's Republic of China and Republic of China (Taiwan) as part of the region of South Tibet. During the 1962 Sino-Indian War, most of Arunachal Pradesh was temporarily captured by the Chinese People's Liberation Army.

Toponymy

Arunachal Pradesh means Land of the Dawn-Lit Mountains, which is the sobriquet for the state in Sanskrit.[12] The state is also known as the Orchid State of India or the Paradise of the Botanists.

History

Early history

Over 1.5 million residents of Arunachal Pradesh belong to the five Tani tribes (Nyishi, Adi, Galo, Apatani, Tagin) supposedly descended from Abotani. The history of the Tani people is found in the ancient libraries of Tibet as the Tani people traded swords and other metals to Tibetans in exchange for meat and wool. Tibetans referred to the Tani people as the Lhobhas; lho means south and bha means people.[13] Apart from these groups, other Tibeto-Burman groups Mishmis, Chutias, Nocte, Tangsa and Wancho also occupied different regions of the state.

Medieval period

Northwestern parts of this area came under the control of the Monpa kingdom of Monyul, which flourished between 500 B.C. and 600 A.D. The Monpa and Sherdukpen keep historical records of the existence of local chiefdoms in the northwest as well. The remaining parts of the state, especially the foothills and the plains, were under the control of the Chutia Kings of Assam.

Recent excavations of ruins of Hindu temples, such as the 14th century Malinithan at the foot of the Siang hills in West Siang, indicate they were built during the Chutia reign. Another notable heritage site, Bhismaknagar (built-in the 8th century), has led to suggestions that the Chutia people had an advanced culture and administration. The third heritage site, the 400-year-old Tawang Monastery in the extreme north-west of the state, provides some historical evidence of the Buddhist tribal people. The sixth Dalai Lama Tsangyang Gyatso was born in Tawang.

The main archaeological sites of the state include:[14]

| Site | Dated to | Built by |

|---|---|---|

| Bhismaknagar Fort, Roing | 8th-15th century[15] | Chutia kings |

| Bolung Fort, Bolung | 13th century | Chutia kings |

| Dimachung-Betali, West Kameng | 13th century | Chutia kings |

| Gomsi Fort, East Siang | 13th century[16] | Chutia kings |

| Rukmini Fort, Roing | 14th-15th century[17] | Chutia kings |

| Tezu Fort, Roing | 14th-15th century[18] | Chutia kings |

| Naksha Parbat ruins, East Kameng | 14th-15th century[19] | Chutia kings |

| Ita Fort, Itanagar | 14th-15th century[20] | Chutia kings |

| Buroi Fort, Papum Pare | 13th century[21] | Chutia kings |

| Malinithan Temple, Likabali | 13th-14th century[22] | Chutia kings |

| Dirang Dzong, West Kameng | 17th century | Monpa |

| Tawang Monastery, Tawang | 17th century (1680-1681) | Merak Lama Lodre Gyatso |

British India

In 1912–13, the British Indian government made agreements with the indigenous peoples of the Himalayas of northeastern India to establish the North-East Frontier Agency from five tracts of frontier lands.[23]

The McMahon line

In 1913–1914, representatives of the de facto independent state of Tibet and Britain met in India to define the borders of Outer Tibet. British administrator Sir Henry McMahon drew the 550 miles (890 km) McMahon Line as the border between British India and Outer Tibet, placing Tawang and other areas within British India. The Tibetan and British representatives devised the Simla Accord including the McMahon Line,[24] but the Chinese representatives did not concur.[25] The Simla Accord denies other benefits to China while it declines to assent to the Accord.[26]

The Chinese position was that Tibet was not independent from China and could not sign treaties, so the Accord was invalid, like the Anglo-Chinese (1906) and Anglo-Russian (1907) conventions.[27] British records show that the condition for the Tibetan government to accept the new border was that China must accept the Simla Convention. As Britain was not able to get an acceptance from China, Tibetans considered the MacMahon line invalid.[25]

In the time that China did not exercise power in Tibet, the line had no serious challenges. In 1935, a Deputy Secretary in the Foreign Department, Olaf Caroe, "discovered" that the McMahon Line was not drawn on official maps. The Survey of India published a map showing the McMahon Line as the official boundary in 1937.[28] In 1938, two decades after the Simla Conference, the British finally published the Simla Accord as a bilateral accord and the Survey of India published a detailed map showing the McMahon Line as a border of India. In 1944, Britain established administrations in the area, from Dirang Dzong in the west to Walong in the east.

Sino-Indian War

India became independent in 1947 and the People's Republic of China (PRC) was established in 1949. The new Chinese government still considered the McMahon Line invalid.[25] In November 1950, the PRC was poised to take over Tibet by force, and India supported Tibet. Journalist Sudha Ramachandran argued that China claimed Tawang on behalf of Tibetans, though Tibetans did not claim Tawang is in Tibet.[29]

What is now Arunachal Pradesh was established as the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) in 1954 and Sino-Indian relations were cordial until 1960. Resurgence of the border disagreement was a factor leading to the Sino-Indian War in 1962, during which China captured most of Arunachal Pradesh. However, China soon declared victory, withdrew back to the McMahon Line and returned Indian prisoners of war in 1963.[30][31][32]

The war resulted in the termination of barter trade with Tibet, although since 2007 the Indian government has shown signs of wanting to resume barter trade.[33]

Renaming

The North-East Frontier Agency was renamed as Arunachal Pradesh by Sri Bibhabasu Das Shastri, the Director of Research and K.A.A. Raja, the Chief Commissioner of Arunachal Pradesh on 20 January 1972, and it became a union territory. Arunachal Pradesh became a state on 20 February 1987.

Recent assertions

In January 2007, the Dalai Lama said that both Britain and Tibet had recognised the McMahon Line in 1914.[35] In 2008, he said that "Arunchal Pradesh was a part of India under the agreement signed by Tibetan and British representatives".[36] According to the Dalai Lama, "In 1962 during the India-China war, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) occupied all these areas (Arunachal Pradesh) but they announced a unilateral ceasefire and withdrew, accepting the current international boundary".[37]

In recent years, China has occasionally asserted its claims on Tawang. India has rebutted these claims and informed the Chinese government that Tawang is an integral part of India. India reiterated this to China when the two prime ministers met in Thailand in October 2009. A report that the Chinese Army had briefly invaded Arunachal Pradesh in 2016 was denied by India's Minister of State for Home Affairs, Kiren Rijiju.[38] In April 2017, China strongly objected to a visit to Tawang by the Dalai Lama, as it had to an earlier visit by the US ambassador to India.[39] China had objected to the Dalai Lama's previous visits to the area.[40]

Insurgency

Arunachal Pradesh has faced threats from insurgent groups, notably the National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN), who are believed to have base camps in the districts of Changlang and Tirap.[41] These groups seek to decrease the influence of Indian government in the region and merge part of Arunachal Pradesh into Nagaland.

The Indian army is present along the Tibetan border to thwart any Chinese incursion. Under the Foreigners (Protected Areas) Order 1958 (India), Inner Line Permits (ILPs) are required to enter Arunachal Pradesh through any of its checkgates on the border with Assam. China renamed six places in Arunachal Pradesh in 2017 and these new names have started to appear on Chinese maps.

Politics

Arunachal Pradesh suffered political crisis between April 2016 and December 2016. The Indian National Congress Chief Minister Nabam Tuki replaced Jarbom Gamlin as the Chief Minister of Arunachal Pradesh on 1 November 2011 and continued until January 2016. After a political crisis in 2016, President's rule was imposed ending his tenure as the chief minister. In February 2016, Kalikho Pul became the Chief Minister when 14 disqualified MLAs were reinstated by the Supreme Court. On 13 July 2016, the Supreme Court quashed the Arunachal Pradesh Governor J.P. Rajkhowa's order to advance the Assembly session from 14 January 2016 to 16 December 2015, which resulted in President's rule in Arunachal Pradesh. As a result, Nabam Tuki was reinstated as the Chief Minister of Arunachal Pradesh on 13 July 2016. But hours before floor test, he resigned as the chief minister on 16 July 2016. He was succeeded by Pema Khandu as the INC Chief Minister who later joined PPA in September 2016 along with majority of MLAs. Pema Khandu further joined BJP in December 2016 along with majority of MLAs. Arunachal Pradesh becomes 2nd NE state to achieve ODF status[42]

Geography

Arunachal Pradesh is located between 26.28° N and 29.30° N latitude and 91.20° E and 97.30° E longitude and has an area of 83,743 km2 (32,333 sq mi).

The highest peak in the state is Kangto, at 7,060 metres (23,160 ft). Nyegi Kangsang, the main Gorichen peak, and the Eastern Gorichen peak are other tall Himalaya peaks. The state's mountain ranges, in the extreme East of India, are described as "the place where the sun rises" in historical Indian texts and named the Aruna Mountains, which inspired the name of the state. The villages of Dong (more accessible by car, and with a lookout favoured by tourists) and Vijaynagar (on the edge of Myanmar) receive the first sunlight in all of India.

Major rivers of Arunachal Pradesh include the Kameng, Subansiri, Siang (Brahmaputra), Dibang, Lohit and Noa Dihing rivers. Subsurface flows and summer snow melt contribute to the volume of water. Mountains until the Siang river are classified as the Eastern Himalayas. Those between the Siang and Noa Dihing are classified as the Mishmi Hills that may be part of the Hengduan Mountains. Mountains south of the Noa Dihing in Tirap and Longding districts are part of the Patkai Range.

Climate

The climate of Arunachal Pradesh varies with elevation. The low altitude (100 – 1500 m) areas have a Humid subtropical climate. High altitude and very high altitude areas (3500 – 5500 m) have a subtropical highland climate and alpine climate. Arunachal Pradesh receives 2,000 to 5,000 millimetres (79 to 197 in) of rainfall annually,[43] 70 - 80% obtained between May and October.

Biodiversity

Arunachal Pradesh has among the highest diversity of mammals and birds in India. There are around 750 species of birds[44] and more than 200 species of mammals[45] in the state.

In the year 2000 Arunachal Pradesh was covered with 63,093 km2 (24,360 sq mi) of tree cover[46] (77% of its land area). Arunachal's forests account for one-third of habitat area within the Himalayan biodiversity hot-spot.[47] In 2013, 31,273 km2 (12,075 sq mi) of Arunachal's forests were identified as part of a vast area of continuous forests (65,730 km2 or 25,380 sq mi, including forests in Myanmar, China and Bhutan) known as Intact forest landscapes.[48] It harbours over 5000 plants, about 85 terrestrial mammals, over 500 birds and many butterflies, insects and reptiles.[49] At the lowest elevations, essentially at Arunachal Pradesh's border with Assam, are Brahmaputra Valley semi-evergreen forests. Much of the state, including the Himalayan foothills and the Patkai hills, are home to Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests. Toward the northern border with Tibet, with increasing elevation, come a mixture of Eastern and Northeastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests followed by Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows and ultimately rock and ice on the highest peaks. It supports many medicinal plants and within Ziro valley of Lower Subansiri district 158 medicinal plants are being used by its inhabitants.[50] The mountain slopes and hills are covered with alpine, temperate, and subtropical forests of dwarf rhododendron, oak, pine, maple and fir.[51] The state has Mouling and Namdapha national parks.

A new subspecies of hoolock gibbon has been described from the state which has been named as Mishmi Hills hoolock H. h. mishmiensis.[52] Three new giant flying squirrels were also described from the state during the last one and half-decade. These were, Mechuka giant flying squirrel,[53] Mishmi Hills giant flying squirrel,[54] and Mebo giant flying squirrel.[55]

Districts

Arunachal Pradesh comprises two divisions i.e. East and West, each headed by a divisional commissioner and twenty-five districts, each administered by a deputy commissioner.

| Divisions | Districts[56] |

|---|---|

| East (HQ:Namsai) | Lohit District, Anjaw District, Changlang District, Tirap District, Lower Dibang Valley District, East Siang District, Upper Siang District, Namsai District, Siang District, Longding District, Dibang Valley District |

| West (HQ:Lower Subansiri) | Tawang District, West Kameng District, East Kameng District, Papum Pare District, Kurung Kumey District, Kra Daadi District, West Siang District, Lower Siang district, Upper Subansiri District, Papum Pare district, Kamle district, Lower Subansiri District, Pakke-Kessang district, Lepa-Rada district, Shi-Yomi district |

Major towns

Below are the major towns in Arunachal Pradesh.

Municipal councils

- Itanagar Municipal Council

- Pasighat Municipal Council

Economy

The chart below displays the trend of the gross state domestic product of Arunachal Pradesh at market prices by the Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation with figures in billions of Indian Rupees.

| Year | Gross Domestic Product (Billion ₹) |

|---|---|

| 1980 | 1.070 |

| 1985 | 2.690 |

| 1990 | 5.080 |

| 1995 | 11.840 |

| 2000 | 17.830 |

| 2005 | 31.880 |

| 2010 | 65.210 |

| 2014 | 155.880 |

Arunachal Pradesh's gross state domestic product was estimated at US$706 million at current prices in 2004 and US$1.75 billion at current prices in 2012. Agriculture primarily drives the economy. Jhum, the local term used for shifting cultivation is being widely practised among the tribal groups, though owing to the gradual growth of other sources of income in the recent years, it is not being practised as prominently as it was earlier. Arunachal Pradesh has close to 61,000 square kilometres of forests, and forest products are the next most significant sector of the economy. Among the crops grown here are rice, maize, millet, wheat, pulses, sugarcane, ginger, and oilseeds. Arunachal is also ideal for horticulture and fruit orchards. Its major industries are rice mills, fruit preservation and processing units, and handloom handicrafts. Sawmills and plywood trades are prohibited under law.[57] There are many saw mills in AP.[58]

Arunachal Pradesh accounts for a large percentage share of India's untapped hydroelectric potential. In 2008, the government of Arunachal Pradesh signed numerous memorandum of understanding with various companies planning some 42 hydroelectric schemes that will produce electricity in excess of 27,000 MW.[59] Construction of the Upper Siang Hydroelectric Project, which is expected to generate between 10,000 and 12,000 MW, began in April 2009.[60]

Demographics

| Population Growth | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | %± | |

| 1961 | 337,000 | — | |

| 1971 | 468,000 | 38.9% | |

| 1981 | 632,000 | 35.0% | |

| 1991 | 865,000 | 36.9% | |

| 2001 | 1,098,000 | 26.9% | |

| 2011 | 1,382,611 | 25.9% | |

| Source:Census of India[61] First census was carried out in 1961. | |||

Arunachal Pradesh can be roughly divided into a set of semi-distinct cultural spheres, on the basis of tribal identity, language, religion and material culture: the Tibetic-speaking Monpa area bordering Bhutan in the west, the Tani area in the centre of the state, the Mishmi area to the east of the Tani area, the Tai/Singpho/Tangsa area bordering Myanmar, and the Naga area to the south, which also borders Myanmar. In between there are transition zones, such as the Aka/Hruso/Miji/Sherdukpen area, between the Tibetan Buddhist tribes and the animist Tani hill tribes. In addition, there are isolated peoples scattered throughout the state, such as the Sulung.

Within each of these cultural spheres, one finds populations of related tribes speaking related languages and sharing similar traditions. In the Tibetic area, one finds large numbers of Monpa tribespeople, with several subtribes speaking closely related but mutually incomprehensible languages, and also large numbers of Tibetan refugees. Within the Tani area, major tribes include the Nyishi. Apatani also live among the Nyishi, but are distinct. In the centre, one finds predominantly Galo people, with the major sub-groups of Karka, Lodu, Bogum, Lare and Pugo among others, extending to the Ramo and Pailibo areas (which are close in many ways to Galo). In the east, one finds the Adi with many subtribes including Padam, Pasi, Minyong and Bokar, among others. Milang, while also falling within the general Adi sphere, are in many ways quite distinct. Moving east, the Idu, Miju and Digaru make up the Mishmi cultural-linguistic area.

Moving southeast, the Tai Khamti are linguistically distinct from their neighbours and culturally distinct from the majority of other Arunachalese tribes. They follow the Theravada sect of Buddhism. They also exhibit considerable convergence with the Singpho and Tangsa Naga tribes of the same area, all of which are also found in Burma. The Khamptis and Singphos have a huge demographic presence even in the neighbouring state of Assam, in places viz. Naharkatiya, Narayanpur of Lakhimpur districts of Assam. They one of the most recent people group migrated to Arunachal region from Burma and Assam. The Nocte Naga and Wancho Naga are another two major ethnic tribes. Both the tribes exhibit very much cultural similarities. Finally the Deori tribe is also a major community in the state, with their own distinctive identity. They are the descendants of the priestly class of Chutia people who were allowed to continue their livelihood after the defeat of the Chutias. Deoris are one of the only Arunachal tribe in the historical records-which shows they are among the first ethnic groups to inhabit the Himalayas of the districts of Dibang Valley and Lohit, before the arrival of other many tribes in the region between 1600 and 1900.

Literacy has risen in official figures to 66.95% in 2011 from 54.74% in 2001. The literate population is said to number 789,943. The number of literate males is 454,532 (73.69%) and the number of literate females is 335,411 (59.57%).[62]

Religion

Religion in Arunachal Pradesh (2011)[63]

The religious landscape of Arunachal Pradesh is diverse with no single religious group representing the majority of the population. A relatively large percentage of Arunachal's population are nature worshippers (indigenous religions), and follow their own distinct traditional institutions like the Nyedar Namlo by the Nyishi, the Rangfrah by the Tangsa & Nocte, Medar Nelo by the Apatani, the Kargu Gamgi by the Galo and Donyi-Polo Dere by the Adi under the umbrella of the indigenous religion the Donyi-Polo. A small number of Arunachali people have traditionally identified as Hindus,[64] although the number may grow as animist traditions are absorbed into Hinduism. Tibetan Buddhism predominates in the districts of Tawang, West Kameng, and isolated regions adjacent to Tibet. Theravada Buddhism is practised by groups living near the Myanmar border. Around 30% of the population are Christians.[65]

According to the 2011 Indian Census, the religions of Arunachal Pradesh break down as follows:[66]

- Christian: 418,732 (30.26%)

- Hindu: 401,876 (29.04%)

- Others (mostly Donyi-Polo): 362,553 (26.2%)

- Buddhist: 162,815 (11.76%)

- Muslim: 27,045 (1.9%)

- Sikh: 1,865 (0.1%)

- Jain: 216 (<0.1%)

Languages

The speakers of major languages of the state according to the 2011 census are Nyishi (28.60%, includes Nyishi, Tagin and Apatani), Adi (17.35%, includes Adi, Galo), Bengali (7.27%, includes Bengali, Chakma and Hajong ), Hindi (7.09%), Nepali (6.89%), Bhotia (4.51%), Assamese (3.9%), Mishmi (3.04%), Nocte (2.9%), Tangsa (2.64%), Wancho (2.19%) and Others (13.62%).

Modern-day Arunachal Pradesh is one of the linguistically richest and most diverse regions in all of Asia, being home to at least 30 and possibly as many as 50 distinct languages in addition to innumerable dialects and subdialects thereof. Boundaries between languages very often correlate with tribal divisions—for example, the Apatani and Nyishi are tribally and linguistically distinct—but shifts in tribal identity and alignment over time have also ensured that a certain amount of complication enters into the picture—for example, the Galo language is and has seemingly always been linguistically distinct from Adi, whereas the earlier tribal alignment of Galo with Adi (i.e., "Adi Gallong") has only recently been essentially dissolved.

The vast majority of languages indigenous to modern-day Arunachal Pradesh belong to the Tibeto-Burman family. The majority of these in turn belong to a single branch of Tibeto-Burman, namely Abo-Tani language. Almost all Tani languages are indigenous to central Arunachal Pradesh, including (moving from west to east) the Nyishi, the Apatani, the Tagin, the Galo, the Bokar, the Adi, the Padam, the Pasi, and the Minyong. The Tani languages are noticeably characterised by an overall relative uniformity, suggesting relatively recent origin and dispersal within their present-day area of concentration. Most of the Tani languages are mutually intelligible with at least one other Tani language, meaning that the area constitutes a dialect chain, as was once found in much of Europe; only Apatani and Milang stand out as relatively unusual in the Tani context. Tani languages are among the better-studied languages of the region.

To the east of the Tani area lie three virtually undescribed and highly endangered languages of the "Mishmi" group of Tibeto-Burman: Idu, Digaru and Miju. A number of speakers of these languages are also found in Tibet. The relationships of these languages, both amongst one another and to other area languages, are as yet uncertain. Further south, one finds the Singpho (Kachin) language, which is primarily spoken by large populations in Myanmar's Kachin State, and the Nocte and Wancho languages, which show affiliations to certain Naga languages spoken to the south in modern-day Nagaland.

To the west and north of the Tani area are found at least one and possibly as many as four Bodic languages, including Dakpa and Tshangla language; within modern-day India, these languages go by the cognate but, in usage, distinct designations Monpa and Memba. Most speakers of these languages or closely related Bodic languages are found in neighbouring Bhutan and Tibet, and Monpa and Memba populations remain closely adjacent to these border regions.

Between the Bodic and Tani areas lie many almost completely undescribed and unclassified languages, which, speculatively considered Tibeto-Burman, exhibit many unique structural and lexical properties that probably reflect both a long history in the region and a complex history of language contact with neighbouring populations. Among them are Sherdukpen, Bugun, Aka/Hruso, Koro, Miji, Bangru and Puroik/Sulung. The high linguistic significance these languages is belied by the extreme paucity of documentation and description of them, even in view of their highly endangered status. Puroik, in particular, is perhaps one of the most culturally and linguistically unique and significant populations in all of Asia from proto-historical and anthropological-linguistic perspectives, and yet virtually no information of any real reliability regarding their culture or language can be found in print.

Finally, other than the Bodic and Tani groups, there are also certain migratory languages which are largely spoken by migratory and central government employees serving in the state in different departments and institutions in modern-day Arunachal Pradesh. They are classified as Non-Tribal as per the provisions of the Constitution of India.

Outside of Tibeto-Burman, one finds in Arunachal Pradesh a single representative of the Tai family, spoken by Tai Khamti tribe, which is closely affiliated to the Shan language of Myanmar's Shan State. Seemingly, Khampti is a recent arrival in Arunachal Pradesh whose presence dates to 18th and/or early 19th-century migrations from northern Myanmar.

In addition to these non-Indo-European languages, the Indo-European languages Assamese, Bengali, English, Nepali and especially Hindi are making strong inroads into Arunachal Pradesh. Primarily as a result of the primary education system—in which classes are generally taught by Hindi-speaking immigrant teachers from Bihar and other Hindi-speaking parts of northern India, a large and growing section of the population now speaks a semi-creolised variety of Hindi as a mother tongue. Hindi acts as a lingua franca for most of the people in the state.[68] Despite, or perhaps because of, the linguistic diversity of the region, English is the only official language recognised in the state.

Transport

Air

Itanagar Airport, a Greenfield project serving Itanagar is being planned at Holongi at a cost of Rs. 6.50 billion.[69] Alliance Air operates the only scheduled flights to the state flying from Kolkata via Guwahati to Pasighat Airport. This route commenced in May 2018 under the Government's Regional Connectivity Scheme UDAN following the completion of a passenger terminal at Pasighat Airport in 2017.[70] State-owned Daporijo Airport, Ziro Airport, Along Airport, and Tezu Airport are small and not in operation, but the government has proposed to develop them.[71] Before the state was connected by roads, these airstrips were used to distribute food.

Roads

The main highway of Arunachal Pradesh is the Trans-Arunachal Highway, National Highway 13 (1,293 km (803 mi); formerly NH-229 and NH-52). It originates in Tawang and spans most of the width of Arunachal Pradesh, then crosses south into Assam and ends at Wakro. The project was announced by then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in 2008 for completion by 2015–16, but is not yet completed.

NH-15 through Assam follows the southern border of Arunachal Pradesh. Access to central Arunachal Pradesh has been facilitated by the Bogibeel Bridge, an earthquake-resistant rail and road bridge over the Brahmaputra River in Assam, opened for public use on 25 December 2018 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. A spur highway numbered NH-415 services Itanagar.

State-owned Arunachal Pradesh State Transport Services (APSTS) runs daily bus service from Itanagar to most district headquarters including Tezpur, Guwahati in Assam, Shillong in Meghalaya, and Dimapur in Nagaland.[72][73][74][75]

As of 2007, every village is connected by road, thanks to funding provided by the central government. Every small town has its own bus station with daily bus service. Connections to Assam have increased commerce.

In 2014, two additional east–west highways were proposed: an Industrial Corridor Highway in the lower foothills, and a Frontier Highway along the McMahon Line.[76][77][78][79] The proposed alignment of the Frontier Highway has been published.[80] China has warned India against paving the road.[81]

Railway

Arunachal Pradesh got its first railway line in late 2013 with the opening of the new link line from Harmuti on the main Rangpara North-Murkongselak railway line to Naharlagun in Arunachal Pradesh. The construction of the 33-kilometre 1,676 mm (5 ft 6 in) broad gauge railway line was completed in 2012, and the link became operational after the gauge conversion of the main line from Assam. The state capital Itanagar was added to the Indian railway map on 12 April 2014 via the newly built 20-kilometre Harmuti-Naharlagun railway line, when a train from Dekargaon in Assam reached Naharlagun railway station, 10 kilometres from the centre of Itanagar, a total distance of 181 kilometres.[82][83]

On 20 February 2015 the first through train was run from New Delhi to Naharlagun, flagged off from the capital by the Indian prime minister, Narendra Modi. India plans to eventually extend the railway to Tawang, near the border with China.[84]

Education

The state government is expanding the relatively underdeveloped education system with the assistance of NGOs like Vivekananda Kendra, leading to a sharp improvement in the state's literacy rate. The main universities are the Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly known as Arunachal University), under which come 36 institutions offering regular undergraduate courses as well as teacher education and health sciences and nursing degrees, both under governmental and private managements, Indira Gandhi Technological and Medical Sciences University and Himalayan University[85] as well. The first college, Jawaharlal Nehru College, Pasighat, was established in 1964. The First Technical University is Established in 2014 namely North East Frontier Technical University (NEFTU). In Aalo, West Siang District by The Automobile Society India, New Delhi. There is also a deemed university, the North Eastern Regional Institute of Science and Technology as well as the National Institute of Technology, Arunachal Pradesh, established on 18 August 2010, is located in Yupia (headquarter of Itanagar).[86] NERIST plays an important role in technical and management higher education. The directorate of technical education conducts examinations yearly so that students who qualify can continue on to higher studies in other states.

Of the above institutions, only the following institutions are accredited by NAAC (National Assessment and Accreditation Council), in the order of their grade: Jawaharlal Nehru College, Pasighat (Grade A), St Claret College, Ziro (Grade A), Indira Gandhi Govt. College, Tezu (Grade B++), Rajiv Gandhi University (Grade B), National Institute of Technology, Arunachal Pradesh (Grade B), Dera Natung Government College, Itanagar (Grade B), Govt. College, Bomdila (Grade B), Donyi Polo Govt. College, Kamki (Grade B), and Rang Frah Govt. College, Changeling (Grade C).

There are also trust institutes, like Pali Vidyapith, run by Buddhists. They teach Pali and Khamti scripts in addition to typical education subjects. Khamti is the only tribe in Arunachal Pradesh that has its own script. Libraries of scriptures are in a number of places in Lohit district, the largest one being in Chowkham.

The state has two polytechnic institutes: Rajiv Gandhi Government Polytechnic in Itanagar established in 2002 and Tomi Polytechnic College in Basar established in 2006. There is two law colleges. 1)Private owned: Arunachal Law Academy at Itanagar. 2) Govt.owned : Jarbom Gamlin Government law college, at Jote. Itanagar. The College of Horticulture and Forestry is affiliated to the Central Agricultural University, Imphal.

State symbols

| Emblem | Emblem of Arunachal Pradesh | |

| Animal | Mithun (Bos frontalis) | |

| Bird | Hornbill (Buceros bicornis) | |

| Flower | Foxtail orchid (Rhynchostylis retusa) | |

| Tree | Hollong (Dipterocarpus macrocarpus)[87] | |

See also

- Cuisine of Arunachal Pradesh

- Arunachal Scouts

- Arunachal Pradesh Police

- List of institutions of higher education in Arunachal Pradesh

- List of people from Arunachal Pradesh

- Ministry for Development of North Eastern Region

- Religion in Arunachal Pradesh

- Sino-Indian border dispute

References

- Government Archived 7 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Mishra, BD (30 September 2017). "Retired Armyman BD Mishra Appointed New Arunachal Governor". NDTV News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- "Pema Khandu sworn in as Chief Minister of Arunachal Pradesh". The Hindu.

- "BJP forms govt in Arunachal Pradesh". The Hindu. Arunachal Pradesh. 31 December 2016. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 47th report (July 2008 to June 2010)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. pp. 122–126. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "Basic Statistical Figure of Arunachal Pradesh" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "Symbols of Arunachal Pradesh". knowindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- "Symbols of Arunachal Pradesh". Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- "State Trees and Flowers of India". flowersofindia.net. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "State Tree of Arunachal Pradesh" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- "'We Wake Up at 4 am': Arunachal Pradesh CM Pema Khandu Wants Separate Time Zone". Outlook. 12 June 2017. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018.

- Usha Sharma (2005). Discovery of North-East India. Mittal Publications. p. 65. ISBN 978-81-8324-034-5.

- "Official Web Page of Government of Arunachal Pradesh". Archived from the original on 20 March 2012.

- Baruah, Dr. Swarnalata (2004). Chutia Jaatir Buranji. Guwahati: Banalata Publications.

- The site can be dated between 8th-15th century

- Indian Archeology-1996-97

- The site is dated to 14th-15th century

- Chattopadhyay, S., History and archaeology of Arunachal Pradesh, p. 71

- Borah,D.K.Archaeological ruins of Naksabat, p.32

- The site is dated to 14th-15th century

- Barua, K.L.,Early History of Kamrupa,p.271.

- Thakur, A.K, Pre-historic Archeological Remains of Arunachal Pradesh and People's perception: An Overview, p.6

- "Arunachal Pradesh - Government and society". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Simla Convention". Tibetjustice.org. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- Tsering Shakya (1999). The Dragon in the Land of Snows: A History of Modern Tibet Since 1947. Columbia University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-231-11814-9. Archived from the original on 30 March 2017.

- Lamb, Alastair, The McMahon line: a study in the relations between India, China and Tibet, 1904 to 1914, London, 1966, p529

- Ray, Jayanta Kumar (2007). Aspects of India's International relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World. History of science, philosophy, and culture in Indian civilization: Towards independence. Pearson PLC. p. 202. ISBN 978-81-317-0834-7.

- Ray, Jayanta Kumar (2007). Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World. Pearson Education India. p. 203. ISBN 978-81-317-0834-7. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- Ramachandran, Sudha (27 June 2008). "China toys with India's border". South Asia. Archived from the original on 22 November 2009.

- Maxwell, Neville (1970). India's China War. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 978-0224618878.

- A.G. Noorani, "Perseverance in peace process Archived 26 March 2005 at the Wayback Machine", India's National Magazine, 29 August 2003.

- Manoj Joshi, "Line of Defence", Times of India, 21 October 2000

- "PM to visit Arunachal in mid-Feb".

- Richardson 1984, p. 210.

- "Tawang's history affirms China's sovereignty - Global Times". Archived from the original on 16 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- "Tawang is part of India: Dalai Lama". TNN. 4 June 2008. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- "Dalai Lama's visit to Arunachal nostalgic: Top aide" Hindustan Times dated Dharamsala, 8 November 2009

- "Dalai Lama in Tawang: What next". 15 April 2017. Archived from the original on 24 April 2017.

- "Thousands flock to see Dalai Lama in Indian state". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016.

- "Apang rules out Chakma compromise". Calcutta, India: Telegraphindia.com. 12 August 2003. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011.

- "Arunachal becomes 2nd NE state to achieve ODF status". Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- Dhar, O. N.; Nandargi, S. (1 June 2004). "Rainfall distribution over the Arunachal Pradesh Himalayas". Weather. 59 (6): 155–157. Bibcode:2004Wthr...59..155D. doi:10.1256/wea.87.03. ISSN 1477-8696.

- A. U. Choudhury (2006). A pocket guide to the birds of Arunachal Pradesh. Gibbon Books & The Rhino Foundation for Nature in North East India, Guwahati, India 109pp. [Party supported by Oriental Bird Club, UK]. ISBN 81-900866-5-0.

- A. U. Choudhury (2003). The mammals of Arunachal Pradesh. Regency Publications, New Delhi. 140pp, illus, plates. ISBN 81-87498803, 9788187498803.

- Hansen, M. C.; Potapov, P. V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S. A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S. V.; Goetz, S. J. (15 November 2013). "High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change". Science. 342 (6160): 850–853. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..850H. doi:10.1126/science.1244693. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 24233722. S2CID 23541992.

- Mittermeier, Russell A. (2004). Hotspots revisited. Cemex.

- Potapov, Peter; Hansen, Matthew C.; Laestadius, Lars; Turubanova, Svetlana; Yaroshenko, Alexey; Thies, Christoph; Smith, Wynet; Zhuravleva, Ilona; Komarova, Anna (1 January 2017). "The last frontiers of wilderness: Tracking loss of intact forest landscapes from 2000 to 2013". Science Advances. 3 (1): e1600821. Bibcode:2017SciA....3E0821P. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600821. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5235335. PMID 28097216.

- Govt of Arunachal Pradesh. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Kala, CP (2005). "Ethnomedicinal botany of the Apatani in the Eastern Himalayan region of India". J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 1: 11. doi:10.1186/1746-4269-1-11. PMC 1315349. PMID 16288657.

- Champion, Sir HG, and Shiam Kishore Seth. (1968). A revised survey of the forest types of India(1968).CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- A. U. Choudhury (2013). Description of a new subspecies of hoolock gibbon Hoolock hoolock from North East India. The Newsletter & Journal of the Rhino Foundation for nat. in NE India 9: 49–59.

- A. U. Choudhury (2007). A new flying squirrel of the genus Petaurista Link from Arunachal Pradesh in north-east India. Newsletter & J. Rhino Foundation NE India 7: 26-32, plates.

- A. U. Choudhury (2009). One more new species of giant flying squirrel of the genus Petaurista Link, 1795 from Arunachal Pradesh in north-east India. Newsletter & J. Rhino Foundation NE India 8: 27-35, plates".

- A. U. Choudhury (2013). Description of a new species of giant flying squirrel of the genus Petaurista Link, 1795 from Siang basin, Arunachal Pradesh in North East India. The Newsletter & Journal of the Rhino Foundation for nat. in NE India 9: 30–38".

- "Administrative jurisdiction of divisions and districts" (PDF). Government of Arunachal Pradesh. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- Arunachal Pradesh Economy Archived 8 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, This Is My India

- "Economy of Arunachal Pradesh". Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

- "Massive dam plans for Arunachal". Indiatogether.org. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- "India pre-empts Chinese design in Arunachal". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 22 May 2013.

- "Census Population" (PDF). Census of India. Ministry of Finance India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "Census of India: Provisional Population Tables – Census 2011" (PDF). Censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- "Population by religion community – 2011". Census of India, 2011. The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 25 August 2015.

- Katiyar, Prerna (19 November 2017). "How churches in Arunachal Pradesh are facing resistance over conversion of tribals". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017.

- "Census of India : C-1 Population By Religious Community". Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Census of India – Religious Composition". Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. Archived from the original on 13 September 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- "Census of India Website : Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". www.censusindia.gov.in.

- "How Hindi became the language of choice in Arunachal Pradesh". Archived from the original on 11 December 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "PMO ends tussle between AAI and Arunachal". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 28 July 2012. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012.

- "Arunachal's first commercial flight lands at Pasighat airport". The Times of India. 22 May 2018.

- "Govt considering setting up of 3 greenfield airports in NE". The Hindu Businessline. 13 August 2014.

- "Itanagar-Dimapur bus service flagged off". Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- "Night coach bus services introduced". Archived from the original on 3 January 2017.

- "PSTS". Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Top officials to meet to expedite road building along China border". Dipak Kumar Dash. timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Narendra Modi government to provide funds for restoration of damaged highways". dnaindia. 20 September 2014. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Indian Government Plans Highway Along Disputed China Border". Ankit Panda. thediplomat.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "Govt planning road along McMohan line in Arunachal Pradesh: Kiren Rijiju". Live Mint. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "China warns India against paving road in Arunachal". Ajay Banerjee. tribuneindia.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- "Arunachal Pradesh Capital Itanagar Put on India's Railway Map". indiatimes.com. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Arunachal Pradesh now on railway map, train reaches Naharlagun, a town near capital Itanagar". timesofindia-economictimes. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Kalita, Prabin (20 February 2015). "Modi to flag off first train from Arunachal to Delhi". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 23 February 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- "Quality higher education". articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- "NIT Arunachal Pradesh, Govt. of India". Archived from the original on 24 February 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- "Arunachal Pradesh Symbols". knowindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 19 November 2017.

External links

Government

General information

- Arunachal Pradesh Encyclopædia Britannica entry

- Arunachal Pradesh at Curlie