Barak Valley

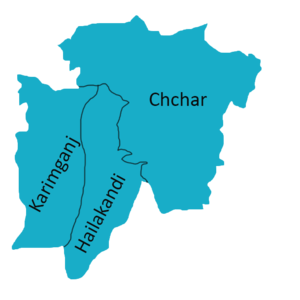

The Barak Valley[1] is located in the southern region of the Indian state of Assam. The main city of the valley is Silchar. The region is named after the Barak river. The Barak valley mainly consists of three administrative districts of Assam - namely Cachar, Karimganj, and Hailakandi. Among these three districts, Cachar and Hailakandi historically belonged to the Kachari Kingdom before the British Raj, whereas Karimganj belonged to the Sylhet Region then Assam province, which was then separated from Sylhet after the 1947 referendum; with the rest of Sylhet falling under East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) and Karimganj under India.

Demography

Language and religion

Bengali is the official language of Barak Valley constituting over 90% of the valley, along with English being served as co-official language of the valley.[2] Majority of the people of Barak Valley speak Indo-European languages including Bengali, Hindi, Sylheti, Bhojpuri, Nepali, Bishnupriya among others. Non Indo-European languages spoken in the valley include Khasi, Mizo, Dimasa, Hmar, Manipuri, Rongmei and certain other indigenous languages of Northeast India.

Hinduism is the marginally majority religion in the Barak Valley. According to the 2011 census by the Government of India, Barak valley had a population of 3,624,599. The religious composition of the valley population is as follows: Hindus 50% (1,812,141), Muslims 48.1% (1,744,958), Christians 1.6% (58,105), and others 0.3%. Hindus are the majority in Cachar district (59.83%), while Muslims are the majority in Hailakandi district (60.31%) and Karimganj district (56.36%).[3]

History

The region was originally part of the Tripura kingdom. In 1562 Chilarai annexed the Cachar region to the Koch kingdom and administered by his half-brother Kamalnarayan.[4] After the death of Nara Narayan, the kingdom, which came to be called the kingdom of Khaspur, became independent and was ruled by the descendants of Kamalnarayan. In the 17th-century, the last Koch ruler's daughter married the king of the Kachari kingdom, and the rule of Khaspur passed into the hands of the Kachari rulers, who eventually moved their capital from Maibang to Khaspur.[5]

The Kachari kingdom was annexed to British-India in 1832. The headquarters of the district was Silchar. The British Companies established a very large number of Tea Gardens (total 157) in the area and Silchar emerged as a very important center in this part of the country.

Inclusion of Karimganj

In 1947, when a plebiscite was held in Sylhet with majority voting for incorporation with Pakistan. The Sylhet district was divided into two; the easternmost subdivision of Sylhet which is known as Karimganj remained with India whereas the rest joined East Bengal. Geographically the region is surrounded by hills from all three sides except its western plain boundary with Bangladesh. Nihar Ranjan Roy, author of Bangalir Itihash, claims that "South Assam / Northeastern Bengal or Barak Valley is the extension of the Greater Surma/Meghna Valley of Bengal in every aspect from culture to geography".[6]

Assam's Surma Valley (now partly in Bangladesh) had Muslim-majority population. On the eve of partition, hectic activities intensified by the Muslim League as well Congress with the former having an edge. A referendum had been proposed for Sylhet District. Abdul Matlib Mazumdar along with Basanta Kumar Das (then Home Minister of Assam) travelled throughout the valley organising the Congress and addressing meetings educating the masses about the outcome of partition on the basis of religion.[7] On 20 February 1947 Moulvi Mazumdar inaugurated a convention – Assam Nationalist Muslim's Convention at Silchar. Thereafter another big meeting was held at Silchar on 8 June 1947.[8] Both the meetings, which were attended by a large section of Muslims paid dividend. He was also among the few who were instrumental in retaining the Barak Valley region of Assam, especially Karimganj with India.[9][10] Mazumdar was the leader of the delegation that pleaded before the Radcliffe Commission that ensured that a part of Sylhet (now in Bangladesh) remains with India despite being Muslim-majority (present Karimganj district).[11][12]

List of districts in Barak valley

There are three district in Barak Valley.

Wildlife

The Asian elephant has already vanished from most of the valley.[13][14][15] Barail is the only wildlife sanctuary of the Barak valley region. It was initiated by noted naturalist Dr Anwaruddin Choudhury, who originally hailed from this region in the early 1980s.[16] This sanctuary was ultimately notified in 2004. There are thirteen reserve forests in the valley comprising six in Karimganj, five in Cachar, and two are in Hailakandi. [17][18] The Patharia hills reserve forest of Karimganj is the habitat of many mammals and was recommended to upgrade as 'Patharia hills wildlife sanctuary'.[19] The southern part was also recommended as 'Dhaleswari' wildlife sanctuary.[20]

Constituencies

Barak Valley has two Lok Sabha seats.

Barak Valley has fifteen Assam Legislative Assembly seats.

- Badarpur

- Algapur

- Hailakandi

- Katlicherra

- Karimganj South

- Karimganj North

- Ratabari

- Patharkandi

- Katigorah

- Dholai

- Udharbond

- Sonai

- Silchar

- Barkhola

- Lakhipur

Notable people

- Abdul Matlib Mazumdar, freedom fighter, cabinet minister in the last ministry during the British period and then after independence, in the first and subsequent ministries. Assam's first Agriculture, Veterinary, & Local self-government minister

- Moinul Hoque Choudhury, ex-Minister of Industries during Indira Gandhi regime, established All India Radio, National Institute of Technology, Silchar, Hindustan Paper Mill at Panchgram and Sugar Mill at Anipur

- Debojit Saha, singer and television host

- B. B. Bhattacharya, former Vice-Chancellor, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi

- Kalika Prasad Bhattacharya, singer

Notes

- (Tunga 1995, p. 1)

- India, Press Trust of (9 September 2014). "Govt withdraws Assamese as official language from Barak valley". Business Standard India. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Indian Census Archived 14 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- (Bhattacharjee 1994:71)

- (Bhattacharjee 1994:72)

- Ray, Niharranjan (1 January 1980). Bangalir itihas (in Bengali). Paschimbanga Samiti.

- Chowdhury, Dewan Nurul Anwar Husain. "Sylhet Referendum, 1947". en.banglapedia.org. Banglapedia. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Bhattacharjee, J. B. (1977). Cachar under British Rule in North East India. Radiant Publishers, New Delhi.

- Barua, D. C. (1990). Moulvi Matlib Mazumdar- as I knew him. Abdul Matlib Mazumdar – birth centenary tributes, pp. 8–9.

- Purkayashta, M. (1990). Tyagi jananeta Abdul Matlib Mazumdar. The Prantiya Samachar (in Bengali). Silchar, India.

- Roy, S. K. (1990). Jananeta Abdul Matlib Mazumdar (in Bengali). Abdul Matlib Mazumdar – birth centenary tributes, pp. 24–27.

- "Assam Election Results - What does it mean for Bangladesh?". thedailystar.net. The Daily Star. 21 May 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.

- Talukdar, N.R., Choudhury, P. (2017) Conservation status of Asiatic elephant in southern Assam, India. Gajah 47:18–23.

- Choudhury, A.U. (1999). Status and Conservation of the Asian elephant Elephas maximus in north-eastern India. Mammal Review 29(3): 141-173.

- Choudhury, A.U. (2004). Vanishing habitat threatens Phayre’s leaf monkey. The Rhino Found. NE India Newsletter 6:32-33.

- Choudhury, A.U. (1989). Campaign for wildlife protection:national park in the Barails. WWF-Quarterly No. 69,10(2): 4-5.

- Choudhury, A.U. (2005). Amchang, Barail and Dihing-Patkai – Assam’s new wildlife sanctuaries. Oryx 39(2): 124-125.

- Talukdar, N.R., Singh, B., Choudhury, P. (2018) Conservation status of some endangered mammals in Barak Valley, Northeast India. Journal of Asia-Pacific Biodiversity 11:167–172.

- Talukdar, N.R., Choudhury, P. (2017). Conserving wildlife wealth of Patharia Hills reserve Forest, Assam, India: a critical analysis. Global Ecology and Conservation 10:126–138.

- Choudhury, A.U. (1983). Plea for a new wildlife refuge in eastern India. Tigerpaper 10(4):12-15.

References

- Bhattacharjee, J B (1994), "Pre-colonial Political Structure of Barak Valley", in Sangma, Milton S (ed.), Essays on North-east India: Presented in Memory of Professor V. Venkata Rao, New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company, pp. 61–85

- Tunga, S. S. (1995). Bengali and Other Related Dialects of South Assam. Delhi: Mittal Publications. Retrieved 19 February 2013.