African Americans in the Revolutionary War

In the American Revolution, gaining freedom was the strongest motive for Black enslaved people who joined the Patriot or British armies. It is estimated that 20,000 African Americans joined the British cause, which promised freedom to enslaved people, as Black Loyalists. Around 9,000 African Americans became Black Patriots.[1]

As between 200,000 and 250,000 soldiers and militia served the American cause during the revolution in total, that would mean Black soldiers made up approximately four percent of the Patriots' numbers. Of the 9,000 Black soldiers, 5,000 were combat dedicated troops.[2] Notably, the average length of time in service for an African American soldier during the war was four and a half years (due to many serving for the whole eight-year duration), which was eight times longer than the average period for white soldiers. Meaning that while they were only four percent of the manpower base, they comprised around a quarter of the Patriots' strength in terms of man-hours, though this includes supportive roles.[3]

In contrast, about 20,000 escaped enslaved people joined and fought for the British army.[4] Much of this number was seen after Dunmore's Proclamation, and subsequently the Philipsburg Proclamation issued by Sir Henry Clinton.[5] Though between only 800–2,000 people who were enslaved reached Dunmore himself, the publication of both proclamations incentive nearly 100,000 enslaved people to escape across the American Colonies, many lured by the promise of freedom.[6]

Crispus Attucks was shot dead by British soldiers in the Boston Massacre in 1770 after he shouted, "Kill them! Kill them! Knock them over!" while the soldiers were being battered with shells, ice, and coal by a mob armed with clubs.[7] He is considered an iconic martyr of Patriots. [8]

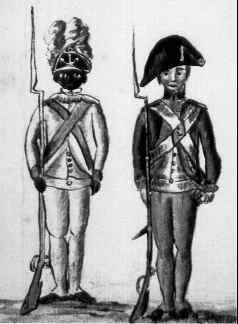

African-American Patriots

Prior to the revolution, many free African Americans supported the anti-British cause, most famously Crispus Attucks, believed to be the first person killed at the Boston Massacre. At the time of the American Revolution, some Black men had already enlisted as Minutemen. Both free and enslaved Africans had served in private militias, especially in the North, defending their villages against attacks by Native Americans. In March 1775, the Continental Congress assigned units of the Massachusetts militia as Minutemen. They were under orders to become activated if the British troops in Boston took the offensive. Peter Salem, who had been freed by his owner to join the Framingham militia, was one of the Black men in the military. He served for nearly five years.[10] In the Revolutionary War, slave owners often let the people they enslaved to enlist in the war with promises of freedom, but many were put back into slavery after the conclusion of the war.[11]

In April 1775, at Lexington and Concord, Black men responded to the call and fought with Patriot forces. Prince Estabrook was wounded some time during the fighting on 19 April, probably at Lexington.[12] The Battle of Bunker Hill also had African-American soldiers fighting along with white Patriots, such as Peter Salem;[13] Salem Poor, Barzillai Lew, Blaney Grusha, Titus Coburn, Alexander Ames, Cato Howe, and Seymour Burr. Many African Americans, both enslaved and free, wanted to join with the Patriots. They believed that they would achieve freedom or expand their civil rights.[14] In addition to the role of soldier, Black men also served as guides, messengers, and spies.

American states had to meet quotas of troops for the new Continental Army, and New England regiments recruited Black enslaved people by promising freedom to those who served in the Continental Army. During the course of the war, about one-fifth of the men in the northern army were Black.[15] At the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, Baron Closen, a German officer in the French Royal Deux-Ponts Regiment, estimated about one-quarter of the American army to be Black men.[16]

African-American sailors

Because of manpower shortages at sea, both the Continental Navy and Royal Navy signed African Americans into their navies. Even southern colonies, which worried about putting guns into the hands of enslaved people for the army, had no qualms about using Black men to pilot vessels and to handle the ammunition on ships. In state navies, some African Americans served as captains: South Carolina had significant numbers of Black captains.[17] Some African Americans had been captured from the Royal Navy and used by the Patriots on their vessels.

Patriot resistance to using African Americans

Revolutionary leaders began to be fearful of using Black men in the armed forces. They were afraid that enslaved people who were armed would rise against them. Slave owners became concerned that military service would eventually free their people.

In May 1775, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety enrolled enslaved people in the armies of the colony. The action was adopted by the Continental Congress when they took over the Patriot Army. But Horatio Gates in July 1775 issued an order to recruiters, ordering them not to enroll "any deserter from the Ministerial army, nor any stroller, negro or vagabond. . ." in the Continental Army.[18] Most Black men were integrated into existing military units, but some segregated units were formed.

African-American Loyalists in British military service

The British regular army had some fears that, if armed, Black men would start slave rebellions. Trying to placate southern planters, the British used African Americans as laborers, skilled workers, foragers and spies. Except for those Black men who joined Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment, only a few Black men, such as Seymour Burr, served in the British army while the fighting was concentrated in the North. It was not until the final months of the war, when manpower was low, that loyalists used Black men to fight for Britain in the South.[19]

In Savannah, Augusta, and Charleston, when threatened by Patriot forces, the British filled gaps in their troops with African Americans. In October 1779, about 200 Black Loyalist soldiers assisted the British in successfully defending Savannah against a joint French and rebel American attack.[20]

In total, historians estimate that approximately 20,000 Africans, composed primarily of escaped, conscripted, or 'freed' formerly enslaved people, fought for the British army.[21]

Dunmore's proclamation

Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, was determined to maintain British rule in the southern colonies and promised to free those enslaved men of rebel owners who fought for him. On November 7, 1775, he issued a proclamation: "I do hereby further declare all indented servants, Negroes, or others, (appertaining to Rebels,) free, that are able and willing to bear arms, they joining His Majesty's Troops." By December 1775 the British army had 300 enslaved men wearing a military uniform. Sewn-on the breast of the uniform was the inscription "Liberty to Slaves". These enslaved men were designated as "Lord Dunmore's Ethiopian Regiment."

Patriot military response to Dunmore's proclamation

Dunmore's Black soldiers aroused fear among some Patriots. The Ethiopian unit was used most frequently in the South, where the African population was oppressed to the breaking point.[22] As a response to expressions of fear posed by armed Black men, in December 1775, Washington wrote a letter to Colonel Henry Lee III, stating that success in the war would come to whatever side could arm Black men the fastest; therefore, he suggested policy to execute any of the enslaved who would attempt to gain freedom by joining the British effort.[23] Washington issued orders to the recruiters to reenlist the free Black men who had already served in the army; he worried that some of these soldiers might cross over to the British side.

Congress in 1776 agreed with Washington and authorized re-enlistment of free Black men who had already served. Patriots in South Carolina and Georgia resisted enlisting enslaved men as armed soldiers. African Americans from northern units were generally assigned to fight in southern battles. In some Southern states, southern Black enslaved men substituted for their masters in Patriot service.

Black Regiment of Rhode Island

In 1778, Rhode Island was having trouble recruiting enough white men to meet the troop quotas set by the Continental Congress. The Rhode Island Assembly decided to adopt a suggestion by General Varnum and enlist enslaved men in 1st Rhode Island Regiment.[24] Varnum had raised the idea in a letter to George Washington, who forwarded the letter to the governor of Rhode Island. On February 14, 1778, the Rhode Island Assembly voted to allow the enlistment of "every able-bodied negro, mulatto, or Indian man slave" who chose to do so, and that "every slave so enlisting shall, upon his passing muster before Colonel Christopher Greene, be immediately discharged from the service of his master or mistress, and be absolutely free...."[25] The slave owners who enlisted were to be compensated by the Assembly in an amount equal to the market value of the man who had been enslaved.

A total of 88 men who had been enslaved enlisted in the regiment over the next four months, joined by some free Black men. The regiment eventually totaled about 225 men; probably fewer than 140 were Black men.[26] The 1st Rhode Island Regiment became the only regiment of the Continental Army to have segregated companies of Black soldiers.

Under Colonel Greene, the regiment fought in the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778. The regiment played a fairly minor but still-praised role in the battle. Its casualties were three killed, nine wounded, and eleven missing.[27]

Like most of the Continental Army, the regiment saw little action over the next few years, as the focus of the war had shifted to the south. In 1781, Greene and several of his Black soldiers were killed in a skirmish with Loyalists. Greene's body was mutilated by the Loyalists, apparently as punishment for having led Black soldiers against them. Forty of the Black men in his unit were also killed. [28] A Monument to the First Rhode Island Regiment memorializing the bravery of the Black soldiers that fought and died with Greene was erected in 1982 in Yorktown Heights, New York.

Fate of Black Loyalists

On July 21, 1781, as the final British ship left Savannah, more than 5,000 enslaved African Americans were transported with their Loyalist masters for Jamaica or St. Augustine. About 300 Black people in Savannah did not evacuate, fearing that they would be re-enslaved. They established a colony in the swamps of the Savannah River. By 1786, many were back in bondage.

The British evacuation of Charleston in December 1782 included many Loyalists and more than 5,000 Black men. More than half of these were enslaved by the Loyalists; they were taken by their masters for resettlement in the West Indies, where the Loyalists started or bought plantations. The British also settled freed formerly enslaved people in Jamaica and other West Indian islands, eventually granting them land. Another 500 enslaved people were taken to east Florida, which remained under British control.

The British promised freedom to enslaved people who left rebels to side with the British. In New York City, which the British occupied, thousands of refugee enslaved people had migrated there to gain freedom. The British created a registry of people who had escaped slavery, called the Book of Negroes. The registry included details of their enslavement, escape, and service to the British. If accepted, the former enslaved person received a certificate entitling transport out of New York. By the time the Book of Negroes was closed, it had the names of 1,336 men, 914 women, and 750 children, who were resettled in Nova Scotia. They were known in Canada as Black Loyalists. Sixty-five percent of those evacuated were from the South. About 200 formerly enslaved people were taken to London with British forces as free people.[29]

After the war, many freed Black people living in London and Nova Scotia struggled with discrimination, a slow pace of land grants and, in Canada, with the more severe climate. Supporters in England organized to establish a colony in West Africa for the resettlement of Poor Blacks of London, most of whom were formerly enslaved in American. Freetown was the first settlement established of what became the colony of Sierra Leone. Black Loyalists in Nova Scotia were also asked if they wanted to relocate. Many chose to go to Africa, and on January 15, 1792, 1,193 Black people left Halifax for West Africa and a new life. Later the African colony was supplemented by Afro-Caribbean maroons transported by the British from Jamaica, as well as Africans who were liberated by the British in their intervention in the Atlantic slave trade, after Britain prohibited it in 1807.

The African-American Patriots who served the Continental Army, found that the postwar military held no rewards for them. It was much reduced in size, and state legislatures such as Connecticut and Massachusetts in 1784 and 1785, respectively, banned all Blacks, free or enslaved, from military service. Southern states also banned all enslaved men from their militias. North Carolina was among the states that allowed free people of color to serve in their militias and bear arms until the 1830s. In 1792, the United States Congress formally excluded African Americans from military service, allowing only "free able-bodied white male citizens" to serve.[30]

At the time of the ratification of the Constitution in 1789, free Black men could vote in five of the thirteen states, including North Carolina. That demonstrated that they were considered citizens not only of their states but of the United States.[31]

Many enslaved men who fought in the war gained freedom, but others did not. Some owners reneged on their promises to free them after their service in the military.

Some African-American descendants of Revolutionary war veterans have documented their lineage. Professor Henry Louis Gates and Judge Lawrence W. Pierce, as examples, have joined the Sons of the American Revolution based on documenting male lines of ancestors who served.

In the first two decades following the Revolution, northern states abolished slavery, some by a gradual method. In the US as a whole, by 1810 the number of free Black people reached 186,446, or 13.5 percent of all Black people.[32] Northern states abolished slavery by law or in their new constitutions. By 1810, 75 percent of all African Americans in the North were free. By 1840, virtually all African Americans in the North were free.[32]

Although southern state legislatures maintained the institution of slavery, in the Upper South, especially, numerous slaveholders were inspired by revolutionary ideals to free the people they had enslaved. In addition, in this period Methodist, Baptist and Quaker preachers also urged manumission. The proportion of free Black people in the Upper South increased markedly, from less than 1 percent of all Black people to more than 10 percent, even as the number of enslaved people was increasing overall.[33] More than half of the number of free Black people in the United States were concentrated in the Upper South.[33] In Delaware, nearly 75 percent of Black people were free by 1810.[34] This was also a result of a changing economy, as many planters had been converting from labor-intensive tobacco to mixed commodity crops, with less need for intensive labor.

After that period, few enslaved people were freed. The invention of the cotton gin made cultivation of short-staple cotton profitable, and the Deep South was developed for this product. This drove up the demand for labor from people who were enslaved in that developing area, creating a demand for more than one million people to be enslaved to be transported to the Deep South in the domestic slave trade.[35]

The 2000 film, The Patriot, features an African-American character named Occam (played by Jay Arlen Jones). He is an enslaved man who fights in the war in place of his master. After serving a year in the Continental Army, he becomes a free man and continues to serve with the militia until the end of the war.

The 2011 young adult novel, Forge, by Laurie Halse Anderson, follows a teenage African-American youth who escaped from slavery to join the war.[36]

Role of other combatants with African ancestry

While not American-based, a French regiment of colored troops (the Chasseurs-Volontaires de Saint-Domingue) under the command of Comte d'Estaing and one of the largest combatant contingent of color in the American Revolutionary War, fought on behalf of the Patriots in the Siege of Savannah.

See also

- National Liberty Memorial - proposed memorial to commemorate African Americans who fought in the Revolutionary War

- The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, 1855 book

- Afro-Mexicans in the Mexican War of Independence

References

- Nash, "The African Americans' Revolution," at p 254

- Michael Lee Lanning. "African Americans in the Revolutionary War." Page 177.

- Michael Lee Lanning. "African Americans in the Revolutionary War." Page 178.

- https://www.history.com/news/the-ex-slaves-who-fought-with-the-british

- Carnahan, Burrus M. (2007). Act of Justice: Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation and the Law of War. University Press of Kentucky. p. 18. ISBN 0-8131-2463-8

- Bristow, Peggy (1994). We're Rooted Here and They Can't Pull Us Up: Essays in African Canadian Women's History. University of Toronto Press. p. 19. ISBN 0-8020-6881-2.

- "John Adams and the Boston Massacre Trials".

- "Crispus Attucks". Biography. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- Thomas H. O'Connor, The Hub: Boston Past and Present (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2001), p. 56 ISBN 1555535445.

- Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors of the Revolutionary War. Vol. 13, pp. 743–744.

- "Fighting... Maybe for Freedom, but probably not?". History.

- "SALEM, April 25". Essex Gazette. Essex, Massachusetts. 25 April 1775. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- Lisa, C. R. (January 2006). "Peter Salem, American hero!". Footsteps. 8: 36–37 – via ProQuest.

- Foner, 43.

- Liberty! The American Revolution (Documentary) Episode II:Blows Must Decide: 1774–1776. ©1997 Twin Cities Public Television, Inc. ISBN 1-4157-0217-9

- "The Revolution's Black Soldiers" by Robert A. Selig, Ph.D., American Revolution website, 2013-2014

- Foner, 70.

- "Continental Army". United States History. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- Lanning, 145.

- Lanning, 148.

- https://www.history.com/news/the-ex-slaves-who-fought-with-the-british

- White, Deborah; Bay, Mia; Martin, Waldo (2013). Freedon: on My Mind. Bostan: Bedford/St.Martin's. p. 129.

- Malcolm, Joyce Lee (14 May 2014). "Peter's War: A New England Slave Boy and the American Revolution". Yale University Press. Retrieved 25 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- Nell, William C. (1855). "IV, Rhode Island". The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution. Robert F. Wallcut.

- Foner, 205.

- Foner, 75–76.

- Lanning, 76–77.

- Lanning, 79.

- Lanning, 161–162.

- Lanning, 181.

- Abraham Lincoln's Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, June 26, 1857 Archived September 8, 2002, at the Wayback Machine

- Peter Kolchin (1993), American Slavery, p. 81.

- Peter Kolchin (1993), American Slavery, pp. 77–78, 81.

- Kolchin (1993), American Slavery, p. 78.

- Kolchin (1993), American Slavery, p. 87.

- "Sign in - Google Accounts". Sites.google.com. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

Bibliography

- Blanck, Emily. "Seventeen eighty-three: the turning point in the law of slavery and freedom in Massachusetts." New England Quarterly (2002): 24–51. in JSTOR

- Carretta, Vincent. Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (University of Georgia Press, 2011)

- Foner, Philip. Blacks in the American Revolution. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1976 ISBN 0837189462.

- Frey, Sylvia R. Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age (1992) excerpt and text search

- Gilbert, Alan. Black Patriots and Loyalists: Fighting for Emancipation in the War for Independence (University of Chicago Press, 2012)

- Kearse, Gregory S. "The Bucks of America & Prince Hall Freemasonry". Prince Hall Masonic Digest Newspaper, Washington, D.C. ( 2012): 8.

- Lanning, Michael. African Americans in the Revolutionary War. New York: Kensington Publishing, 2000 ISBN 0806527161.

- Nash, Gary B. "The African Americans' Revolution," in Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution (2012) edited by Edward G Gray and Jane Kamensky pp 250–70.

- Nell, William C. The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855) Full text

- Piecuch, Jim. Three Peoples, One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South, 1775-1782 (Univ of South Carolina Press, 2008)

- Quarles, Benjamin.The Negro in the American Revolution. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1961 ISBN 0807846031.

- Whitfield, Harvey Amani. "Black Loyalists and Black Slaves in Maritime Canada." History Compass 5.6 (2007) pp: 1980–1997.

- Wood, Gordon. The American Revolution: A History. New York: Modern Library, 2002 ISBN 0679640576.