Charles Lee (general)

Charles Henry Lee (6 February 1732 [O.S. 26 January 1731] – 2 October 1782) served as a general of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. He also served earlier in the British Army during the Seven Years War. He sold his commission after the Seven Years War and served for a time in the Polish army of King Stanislaus II.

Charles Henry Lee | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Born | 6 February 1732 [O.S. 26 January 1731] Darnhall, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 2 October 1782 (aged 50) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | British Army: 1747–1763 Continental Army: 1775–1780 |

| Rank | British Army: Lieutenant Colonel Polish Army: Major General |

| Unit | 44th Foot, 103rd Foot |

| Commands held | Southern Department of the Continental Army |

| Battles/wars | Seven Years' War |

| Signature | |

Lee moved to North America in 1773 and bought an estate in Virginia. When the fighting broke out in the American War of Independence in 1775, he volunteered to serve with rebel forces. Lee's ambitions to become Commander in Chief of the Continental Army were thwarted by the appointment of George Washington to that post.

In 1776, forces under his command repulsed a British attempt to capture Charleston, which boosted his standing with the army and Congress. Later that year, he was captured by British cavalry under Banastre Tarleton; he was held by the British as a prisoner until exchanged in 1778. During the Battle of Monmouth later that year, Lee led an assault on the British that miscarried. He was subsequently court-martialed and his military service brought to an end. He died in Philadelphia in 1782.

Early life

Lee was born on February 6 1732 [O.S. January 26, 1731][1][2] in Darnhall, Cheshire, England, the son of Major General John Lee [lower-alpha 1][3] and his wife Isabella Bunbury (daughter of Sir Henry Bunbury, 3rd Baronet).[1][3][4] He was sent to King Edward VI School, Bury St Edmunds, a free grammar school, and later to Switzerland, where he became proficient in several languages, including Latin, Greek, and French.[1][2][3][4] His father was colonel of the 55th Foot (later renumbered the 44th) when he purchased a commission on April 9, 1747 for Charles as an ensign in the same regiment.[1][3]

Seven Years' War and after

North America

After completing his schooling, Lee reported for duty with his regiment in Ireland.[1] Shortly after his father's death, on May 2, 1751 he received[4] (or purchased[1]) a lieutenant's commission in the 44th. He was sent with the regiment to North America in 1754 for service in the French and Indian War[1] under Major General Edward Braddock, in what was a front for the Seven Years War between Britain and France. He was with Braddock at his defeat at the Battle of the Monongahela in 1755.[1][3][4] During this time in America, Lee married the daughter of a Mohawk chief.[1][2][5] His wife (name unknown) gave birth to twins.[1][2] Lee was known to the Mohawk, who were allies of the English, as Ounewaterika or "Boiling Water".[1][2][3][4][5]

On June 11, 1756 Lee purchased a Captain's commission in the 44th[1] for the sum of £900.[3][4] The following year he took part in an expedition against the French fortress of Louisbourg, and on July 1, 1758 he was wounded in a failed assault on Fort Ticonderoga.[1][3][4] He was sent to Long Island to recuperate. A surgeon whom he had earlier rebuked and thrashed attacked him.[1][3][4] After recovering, Lee took part in the capture of Fort Niagara in 1759[1][3][4] and Montreal in 1760.[1][3][4] This brought the war in the North American theater to an end by completing the Conquest of Canada.[3][4]

Portugal

Lee went back to Europe, transferred to the 103rd Foot as a major,[1][3][4] and served as a lieutenant colonel in the Portuguese army. He fought against the Spanish during their unsuccessful invasion of the country, and distinguished himself under John Burgoyne at the Battle of Vila Velha.[1][3][4]

Poland

He returned to England in 1763 following the Peace of Paris, which ended the Seven Years' War.[3][4] His regiment was disbanded and he was retired on half pay as a major.[1][3][4] On 26 May 1772, although still inactive, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel.[6][1][3][4]

In 1765 Lee fought in Poland, serving as an aide-de-camp under King Stanislaus II.[1][3][4] After many adventures he came home to England.[3][4] Unable to secure promotion in the British Army, in 1769 he returned to Poland and saw action in the Russo-Turkish War. Although he lost two fingers in a duel he killed his opponent.[1][3][4]

Returning to England again, he found that he was sympathetic to the American colonists in their quarrel with Britain.[1][3][4] He moved to the colonies in 1773 and in 1775 purchased an estate worth £3,000 in Berkeley County, near the home of his friend Horatio Gates. This area is now part of West Virginia.[1][3][4] He spent ten months travelling through the colonies and acquainting himself with patriots.[1][3][4]

American Revolution

Continental Army

Although Lee was generally acknowledged at the Second Continental Congress to be the most capable candidate for the command of the Continental Army, the role was given to George Washington. Lee recognized the sense of giving the position to a native-born American, but expected to be given the role of second-in-command. He was disappointed when that role went to Artemas Ward, whom Lee considered too inexperienced for the job. Lee was appointed Major-General and third in line, but succeeded to second-in-command in 1776 when Ward resigned due to ill health.[7]

Southern command

Lee also received various other titles: in 1776, he was named commander of the so-called Canadian Department, although he never got to serve in this capacity.[1][1][3][4] He was appointed as the first commander of the Southern Department.[1][1][3][4] He served in this post for six months, until he was recalled to the main army. During his time in the South, the British sent an expedition under Henry Clinton to recover Charleston, South Carolina.[3][4] Lee oversaw the fortification of the city.[1] Fort Sullivan was a fortification built out of palmetto logs, later named for commander Col. William Moultrie.[3][4] Lee ordered the army to evacuate the fort because as he said it would only last thirty minutes and all soldiers would be killed.[8] Governor John Rutledge forbade Moultrie to evacuate and the fort held.[3][4] The spongy palmetto logs repelled the cannonball from the British ships.[9] The assault on Sullivan's Island was driven off, and Clinton abandoned his attempts to capture the city. Lee was acclaimed as the "hero of Charleston", although according to some American accounts the credit for the defense was not his.[3][4]

New York and capture

The British capture of Fort Washington and its near 3,000-strong garrison on November 16, 1776, prompted Lee's first overt criticism of Washington. Believing the commander-in-chief's hesitation to evacuate the fort to be responsible for the loss, Lee wrote to Joseph Reed lamenting Washington's indecision, a criticism Washington read when he opened the letter believing it to be official business.[10] As Washington retreated across New Jersey after the defeat at New York, he urged Lee, whose troops were north of New York, to join him. Although Lee's orders were at first discretionary, and although there were good tactical reasons for delaying, his slow progress has been characterized as insubordinate. On December 12, Lee was captured by British troops at White's Tavern in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, while writing a letter to General Horatio Gates complaining about Washington's deficiency.[11][12]

Battle of Monmouth

Lee was released on parole as part of a prisoner exchange in early April 1778 and, while on his way to York, Pennsylvania, was greeted enthusiastically by Washington at Valley Forge. Lee was ignorant of the changes that had occurred during his sixteen-month captivity; he was not aware of what Washington believed to be a conspiracy to install Gates as commander-in-chief or of the reformation of the Continental Army under the tutelage of Baron von Steuben.[13] According to Elias Boudinot, the commissary who had negotiated the prisoner exchange, Lee claimed that "he found the Army in a worse situation than he expected and that General Washington was not fit to command a sergeant's guard." While in York, Lee lobbied Congress for promotion to lieutenant general, and went above Washington's head to submit to it a plan for reorganizing the army in a way that was markedly different from that which Washington had worked long to implement.[14]

Lee's suggestion was for a militia army that avoided competing with a professional enemy in a pitched battle and relied instead on a defensive strategy which would wear down an opposing army with harassing, small-unit actions.[15] After completing his parole, Lee returned to duty with the Continental Army as Washington's second-in-command on May 21.[16] In June, as the British evacuated Philadelphia and marched through New Jersey en route to New York, Washington twice convened war councils to discuss the best course of action. In both, his generals largely agreed that Washington should avoid a major battle, Lee arguing that such a battle would be criminal, though a minority favored a limited engagement. At the second council, Lee argued the Continental Army was no match for the British Army, and favored allowing the British to proceed unimpeded and waiting until French military intervention following the Franco-American alliance could shift the balance in favor of the Americans.[17]

Washington agreed with the minority of his generals who favored an aggressive but limited action. He allocated some 4,500 troops, approximately a third of his army, to a vanguard that could land a heavy blow on the British without risking his army in a general engagement. The main body would follow and provide support if circumstances warranted.[18] He offered Lee command of the vanguard, but Lee turned the job down on the basis that the force was too small for a man of his rank and position.[19][20] Washington gave the position to Major General the Marquis de Lafayette. In his haste to catch the British, Lafayette pushed the vanguard to exhaustion and outran his supplies, prompting Washington to send Lee, who had in the meantime changed his mind, to replace him.[21]

Lee took over on June 27 at Englishtown.[22] The British were at Monmouth Courthouse (modern-day Freehold), six miles (ten kilometres) from Englishtown. Washington was with the main body of just over 7,800 troops and the bulk of the artillery at Manalapan Bridge, four miles (six kilometres) behind Lee.[23] Believing action to be imminent, Washington conferred with the vanguard's senior officers at Englishtown that afternoon but did not offer a battle plan. Lee believed he had full discretion on whether and how to attack and called his own war council after Washington left. He intended to advance as soon as he knew the British were on the move, in the hope of catching their rearguard when it was most vulnerable. In the absence of any intelligence about British intentions or the terrain, Lee believed it would be useless to form a precise plan of his own.[24]

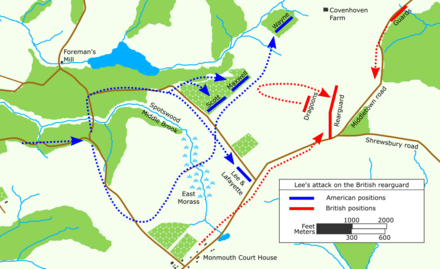

Lee's battle

When news arrived at 05:00 on June 28 that the British were moving, Lee led the vanguard towards Monmouth Court House, where he discovered the British rearguard, which he estimated at around 2,000 troops. He ordered Brigadier General Anthony Wayne with some 550 men to fix the rearguard in place while he led the remainder of the vanguard on a left hook with the intention of outflanking the British, but he neglected to inform his subordinates, Brigadier General Charles Scott and Brigadier General William Maxwell, of his plan. Lee's confidence crept into reports back to Washington that implied "the certainty of success."[25]

As soon as the British commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, received news that his rearguard was being probed, he ordered his main combat division to march back towards Monmouth Court House.[26] Lee became concerned that his right flank would be vulnerable and moved with Lafayette's detachment to secure it.[27] To his left, Scott and Maxwell were not in communication with Lee and not privy to his plan. They became concerned that the arriving British troops would isolate them, and decided to withdraw. To their left, Wayne's isolated troops, having witnessed the British marching back, were also withdrawing.[28][29] Lee witnessed one of Lafayette's units pulling back after a failed attempt to silence some British artillery around the same time as one of his staff officers returned with the news that Scott had withdrawn. With his troops withdrawing without orders, it became clear to Lee that he was losing control of the vanguard, and with his immediate command now only 2,500 strong, he realized his plan to envelop the British rearguard was finished. His priority became the safety of his troops in the face of superior numbers, and he ordered a general retreat.[30]

Although Lee had significant difficulties communicating with his subordinates and could exercise only limited command and control of the vanguard, at unit level the retreat was generally conducted with a discipline that did credit to Steuben's training, and the Americans suffered few casualties. Lee believed he had conducted a model "retrograde manoeuver in the face and under fire of an enemy" and claimed his troops moved with "order and precision." He had remained calm during the retreat but began to unravel at Ker's house. When two of General Washington's aides informed Lee that the main body was still some two miles (three kilometres) away and asked him what to report back, Lee replied "that he really did not know what to say."[31] Crucially, he failed to keep Washington informed of the retreat.[32]

Without any recent news from Lee, Washington had no reason to be concerned as he approached the battlefield with the main body shortly after midday. In the space of some ten minutes, his confidence gave way to alarm as he encountered a straggler bearing the first news of Lee's retreat and then whole units in retreat. None of the officers Washington met could tell him where they were supposed to be going or what they were supposed to be doing. As the commander-in-chief rode on ahead, he saw the vanguard in full retreat but no sign of the British. At around 12:45, Washington found Lee marshalling the last of his command across the middle morass, marshy ground southeast of a bridge over the Spotswood Middle Brook.[33]

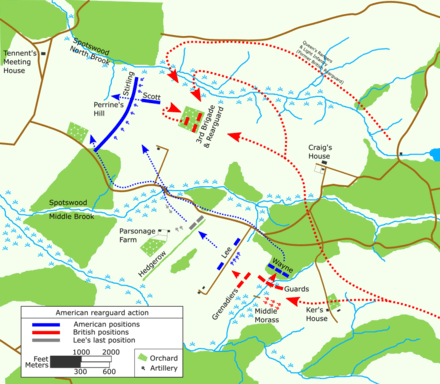

Expecting praise for a retreat he believed had been generally conducted in good order, Lee was uncharacteristically lost for words when Washington asked without pleasantries, "I desire to know, sir, what is the reason – whence arises this disorder and confusion?"[34] When he regained his composure, Lee attempted to explain his actions. He blamed faulty intelligence and his officers, especially Scott, for pulling back without orders, leaving him no choice but to retreat in the face of a superior force, and reminded Washington that he had opposed the attack in the first place.[34][35] Washington was not convinced; "All this may be very true, sir," he replied, "but you ought not to have undertaken it unless you intended to go through with it."[34] Washington made it clear he was disappointed with Lee and rode off to organize the battle he felt his subordinate should have given. Lee followed at a distance, bewildered and believing he had been relieved of command.[36][lower-alpha 2]

With the main body still arriving and the British no more than one-half mile (one kilometre) away, Washington began to rally the vanguard to set up the very defenses Lee had been attempting to organize. He then offered Lee a choice: remain and command the rearguard, or fall back across the bridge and organize the main defenses on Perrine's Hill. Lee opted for the former while Washington departed to take care of the latter.[41][38] Lee fought the counter-attacking British in a rearguard action that lasted no more than thirty minutes, enough time for Washington to complete the deployment of the main body, and at 13:30, he was one of the last American officers to withdraw across the bridge.[42] When Lee reached Perrine's Hill, Washington sent him with part of the former vanguard to form a reserve at Englishtown. At 15:00, Steuben arrived at Englishtown and relieved Lee of command.[43]

Court martial

Even before the day was out, Lee was cast in the role of villain, and his vilification became an integral part of after-battle reports written by Washington's officers.[44] Lee continued in his post as second-in-command immediately after the battle, and it is likely that the issue would have simply subsided if he had let it go. But on June 30, after protesting his innocence to all who would listen, Lee wrote an insolent letter to Washington in which he blamed "dirty earwigs" for turning Washington against him, claimed his decision to retreat had saved the day and pronounced Washington to be "guilty of an act of cruel injustice" towards him. Instead of the apology Lee was tactlessly seeking, Washington replied that the tone of Lee's letter was "highly improper" and that he would initiate an official inquiry into Lee's conduct. Lee's response demanding a court-martial was again insolent, and Washington ordered his arrest and set about obliging him.[45][46][47]

The court convened on July 4, and three charges were laid before Lee: disobeying orders in not attacking on the morning of the battle, contrary to "repeated instructions"; conducting an "unnecessary, disorderly, and shameful retreat"; and disrespect towards the commander-in-chief. The trial concluded on August 12, but the accusations and counter-accusations continued to fly until the verdict was confirmed by Congress on December 5.[48] Lee's defense was articulate but fatally flawed by his efforts to turn it into a personal contest between himself and Washington. He denigrated the commander-in-chief's role in the battle, calling Washington's official account "from beginning to end a most abominable damn'd lie", and disingenuously cast his own decision to retreat as a "masterful manoeuvre" designed to lure the British onto the main body.[49] Washington remained aloof from the controversy, but his allies portrayed Lee as a traitor who had allowed the British to escape and linked him to the previous winter's alleged conspiracy against Washington.[50]

Although the first two charges proved to be dubious,[lower-alpha 3] Lee was undeniably guilty of disrespect, and Washington was too powerful to cross.[54] As the historian John Shy noted, "Under the circumstances, an acquittal on the first two charges would have been a vote of no-confidence in Washington."[55] Lee was found guilty on all three counts, though the court deleted "shameful" from the second and noted the retreat was "disorderly" only "in some few instances." Lee was suspended from the army for a year, a sentence so lenient that some interpreted it as a vindication of all but the charge of disrespect.[56] Lee continued to argue his case and rage against Washington to anyone who would listen, prompting both Lieutenant Colonel John Laurens, one of Washington's aides, and Steuben to challenge him to a duel. Only the duel with Laurens actually transpired, during which Lee was wounded. In 1780, Lee sent such a poorly received letter to Congress that it terminated his service with the army.[57][58][59]

Later life

Lee retired to his Prato Rio property in the Shenandoah Valley, where he bred horses and dogs.[3][4] While visiting Philadelphia, he was stricken with fever and died[1] in a tavern on October 2, 1782.[3][4] He was buried there in the churchyard of Christ Church.[1][3][4] Lee left his property to his sister, Sidney Lee, who died unmarried in 1788.[3]

Legacy

Fort Lee, New Jersey, on the west side of the Hudson River (across the water from Fort Washington, New York), was named for him during his life. Lee, Massachusetts; Lee, New Hampshire; and Leetown, West Virginia[60] were also named for him.

Lee's place in history was further tarnished in the 1850s when George H. Moore, the librarian at the New-York Historical Society, discovered a manuscript dated March 29, 1777, written by Lee while he was the guest of the British as a prisoner of war. It was addressed to the "Royal Commissioners", i.e. Lord Richard Howe and Richard's brother, Sir William Howe, respectively the British naval and army commanders in North America at the time, and detailed a plan by which the British might defeat the rebellion. Moore's discovery, presented in a paper titled The Treason of Charles Lee in 1858, influenced perceptions of Lee for decades.[61] Lee's calumny achieved an orthodoxy in such 19th-century works as Washington Irving's Life of George Washington (1855–1859), George Washington Parke Custis's Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington (1861) and George Bancroft's History of the United States of America, from the Discovery of the American Continent (1854–1878).[62] Although most modern scholars reject the idea that Lee was guilty of treason, it is given credence in some accounts, examples being Willard Sterne Randall's account of the Battle of Monmouth in George Washington: A Life (1997), and Dominick Mazzagetti's Charles Lee: Self Before Country (2013).[63][64][65]

In popular culture

- Lee is featured as the main antagonist in Assassin's Creed III, serving as second in command under Grand Master of the Knights Templar Haytham Kenway.[66][67]

- Lee and his arrest following the retreat during the Battle of Monmouth is depicted in the animated television series Liberty's Kids.[68]

- Lee is a character in the first two seasons of the 2014 AMC television series Turn: Washington's Spies, in which he is blackmailed into becoming a British intelligence operative by Major John André.[69] He is portrayed by Brian T. Finney.[70]

- Lee is a character in Diana Gabaldon's novel Written in My Own Heart's Blood, part of the Outlander series.

- Lee, portrayed in the original Broadway cast by Jon Rua, is a minor character in the 2015 Broadway musical Hamilton, appearing in the songs "Stay Alive," and "Ten Duel Commandments."[71][72]

Footnotes

- John Lee served in 1st Foot Guards and 4th Foot. He was Colonel of 54th Foot and later 44th Foot.

- According to Lender & Stone, the encounter between Washington and Lee "became part of the folklore of the Revolution, with various witnesses (or would-be witnesses) taking increasing dramatic license with their stories over the years."[37] Ferling writes of eyewitness testimony in which a furious Washington, swearing "till the leaves shook on the trees" according to Scott, called Lee a "damned poltroon" and relieved him of command.[38] Chernow reports the same quote from Scott, quotes Lafayette to assert that a "terribly excited" Washington swore and writes that Washington "banished [Lee] to the rear."[35] Bilby & Jenkins attribute the poltroon quote to Lafayette, then write that neither Scott nor Lafayette were present.[39] Lender & Stone are also skeptical, and assert that such stories are apocryphal nonsense which first appeared almost a half century or more after the event, that Scott was too far away to have heard what was said, and that Lee himself never accused Washington of profanity. According to Lender & Stone, "careful scholarship has conclusively demonstrated that Washington was angry but not profane at Monmouth, and he never ordered Lee off the field."[40]

- According to the court-martial transcript, Lee's actions had saved a significant portion of the army.[45] Both Scott and Wayne testified that although they understood Washington wanted Lee to attack, at no stage did he explicitly give Lee an order to do so.[51] Hamilton testified that as he understood it, Washington's instructions allowed Lee the discretion to act as circumstances dictated.[52] Lender and Stone identify two separate orders Washington issued to Lee on the morning of June 28 in which the commander-in-chief made clear his expectation that Lee should attack unless "some very powerful circumstance" dictate otherwise and that Lee should "proceed with caution and take care the Enemy don't draw him into a scrape."[53]

References

- Paul David Nelson (1999). "Lee, Charles". American National Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- Karels, p. 105

- Henry Manners Chichester (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 32. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 344–7.

- John Fiske (1892). . In Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J. (eds.). Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- J. L. Bell. "The Real Story of 'Boiling Water'". Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- "No. 11251". The London Gazette. 23 May 1772. p. 1.

- Thayer 1976 pp. 15–16

- Allen, p. 185

- Allen, p. 186

- Thayer 1976 p. 17

- Thayer 1976 pp. 18–19

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 110

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 110, 113

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 114–117

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 119–120

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 117–118

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 101, 173

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 174–177, 234

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 177–178

- Ferling 2009 p. 176

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 178–182, 187, 188

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 188

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 157–158, 184

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 191–193

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 198, 253–255, 261

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 264–265

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 262–264

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 264–266

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 199

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 266–269

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 268–272

- Ferling 2009 p. 178

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 281–286

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 289

- Chernow 2010 p. 448

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 289–290

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 290

- Ferling 2009 p. 179

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 205

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 290–291

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 291–295

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 298–310, 313

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 315–316

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 391–392

- Ferling 2009 p. 180

- Chernow 2010 p. 452

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 392–393

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 395–396, 400

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 396, 397, 399

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 397–399

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 191–192

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 194

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 195–196

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 396

- Shy 1973, cited in Lender & Stone 2016, p. 396

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 396–397

- Ferling 2009 pp. 180–181

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 400–401

- Chernow 2010 p. 455

- Kenny, Hamill (1945). West Virginia Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning, Including the Nomenclature of the Streams and Mountains. Piedmont, WV: The Place Name Press. p. 366.

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 111–112

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 431

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 112

- Randall 1997 p. 358

- Mazzagetti 2013 p. xi

- "Charles Lee". IGN. Ziff Davis, LLC. 2 December 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- Dyce, Andrew (2012). "Assassin's Creed 3: Our 'Charles Lee Theory'". Game Rant. Warp 100 LLC. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "Battle of Monmouth". The American Revolutionfor Kids. 2 November 2012. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- "John André". AMC. AMC Network Entertainment LLC. 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- Eyerly, Alan (21 April 2015). "'TURN: Washington's Spies' recap: Both sides step up covert activity". LA Times. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- Viagas, Robert (28 June 2016). "Jon Rua Will Play His Final Performance in Hamilton". Playbill. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

- Mead, Rebecca (23 December 2015). "The Thrilling Uncertainty of the Understudy". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved 5 July 2018.

Bibliography

- Allen, Thomas B. (2010). Tories: Fighting for the King in America's First Civil War. HarperCollins. p. 496.

- Axelrod, Alan. "The Real History of the American Revolution" Sterling Publishing, 2007.

- Bilby, Joseph G.; Jenkins, Katherine Bilby (2010). Monmouth Court House: The Battle That Made the American Army. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59416-108-7.

- Chernow, Ron (2010). Washington, A Life (E-Book). London, United Kingdom: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-141-96610-6.

- Ferling, John E. (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York, New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-465-0.

- Karels, Carol (2007). "A Disobedient Servant". The Revolutionary War in Bergen County: The Times that Tried Men's Souls. The History Press. pp. 105–111.

- Lender, Mark Edward; Stone, Garry Wheeler (2016). Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-5335-3.

- Mazzagetti, Dominick (2013). Charles Lee: Self Before Country. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-6238-4.

- McBurney, Christian M. (2013). Kidnapping the enemy. The Special Operations to Capture Generals Charles Lee & Richard Prescott. Westholme Publishing. p. 234. ISBN 978-1594161834.

- McCullough, David. 1776. Simon and Schuster. 2005

- Nelson, Paul David. "Lee, Charles (1732–1782)". American National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- Papas, Phillip. Renegade Revolutionary: The Life of General Charles Lee (New York University Press; 2014) 402 pages;

- Purcell, L. Edward. Who Was Who in the American Revolution. New York: Facts on File, 1993. ISBN 0-8160-2107-4.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1997). George Washington: A Life. New York, New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-2779-2.

- Shy, John (1973). "The American Revolution: The Military Conflict Considered as a Revolutionary War". In Kurtz, Stephen G.; Hutson, James H. (eds.). Essays on the American Revolution. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 121–156. ISBN 978-0-8078-1204-4.

- Thayer, Theodore (1976). The Making of a Scapegoat: Washington and Lee at Monmouth. Kennikat Press. ISBN 0-8046-9139-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Lee. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |