Battle of the Saintes

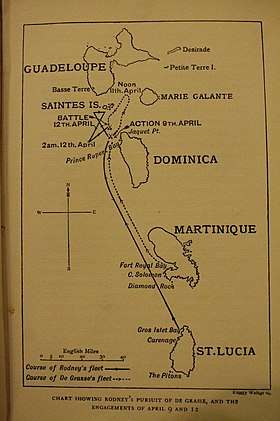

The Battle of the Saintes (known to the French as the Bataille de la Dominique), also known as the Battle of Dominica, was an important naval battle in the Caribbean between the British and the French that took place 9 April 1782 – 12 April 1782, during the American Revolutionary War.[1] The British fleet under Admiral Sir George Rodney defeated a French fleet under the Comte de Grasse, forcing the French and Spanish to abandon a planned invasion of Jamaica.[6]

The battle is named after the Saintes (or Saints), a group of islands between Guadeloupe and Dominica in the West Indies. The French fleet had the year before blockaded the British Army at Chesapeake Bay during the Siege of Yorktown and supported the eventual American victory in their revolution. The battle however had a significant effect on peace negotiations to end the American Revolution.[7]

The French suffered heavy casualties at the Saintes and many were taken prisoner, including the admiral, Comte de Grasse. Four French ships of the line were captured (including the flagship) and one was destroyed. Rodney was credited with pioneering the tactic of "breaking the line" in the battle, though this is disputed.[6][8]

Background

In October 1781, Admiral Comte de Grasse, commander of the French fleet in the West Indies; Francisco Saavedra de Sangronis, General Bureau for the Spanish Indies; and Bernardo de Gálvez, court representative and aide to the Spanish Governor of Louisiana, developed a plan against British forces. The strategic objectives of the Franco-Spanish military forces in the West Indies in this plan were:

- to aid the Americans and defeat the British naval squadron at New York

- to capture the British Windward Islands and

- to conquer Jamaica.[9]

This plan became known as the "De Grasse – Saavedra Convention". The first objective was essentially met by the surrender of the British army under General Cornwallis at the Siege of Yorktown in September 1781. De Grasse and his fleet played a decisive part in that victory, after which they returned to the Caribbean. On arrival in Saint Domingue in November 1781, the admiral was notified to proceed with a plan for the conquest of Jamaica.[10]

Jamaica was the largest and most profitable British island in the Caribbean, mainly because of sugar; it was more valuable to the British economy than all of the thirteen American colonies. King George III wrote to Lord Sandwich, saying that he would risk protecting Britain's important Caribbean islands at the risk of Britain herself, and this was the strategy implemented in 1779.[11] Sugar made up 20% of all British imports and was worth five times as much as tobacco.[12] The French and Spanish were fighting to take over Jamaica in order to expel the British from the West Indies, and to strike a massive blow against the British economy.[13] The courts at Paris and Madrid perceived the invasion of Jamaica as an alternative to the Spanish and French attempts to take Gibraltar, which for two years had been a costly disaster.[14]

While de Grasse waited for reinforcements to undertake the Jamaica campaign, he captured St. Kitts in February 1782. The rest of the Windward Islands - Antigua, St Lucia, and Barbados - still remained under British control. Admiral George Rodney arrived in the Caribbean theatre the following month, bringing reinforcements. These included seventeen ships of the line and gave the British a slight numerical advantage.[15]

On 7 April 1782, de Grasse set out from Martinique with 35 ships of the line, including two 50-gun ships and a large convoy of more than 100 cargo ships, to meet with a Spanish fleet of 12 ships of the line. In addition, de Grasse was to rendezvous with 15,000 troops at Saint Domingue, who were earmarked for the conquest and intended to land on Jamaica's north coast.[15] Rodney, on learning of this, sailed from St Lucia in pursuit with 36 ships of the line the following day.[16]

The British hulls by this time had been given copper sheathing to protect them from marine growth and fouling, as well as salt water corrosion. This dramatically improved speed and sailing performance as a whole in good wind.[17]

The Lines

The British flagship was HMS Formidable under Admiral Rodney. Second in command was Admiral Samuel Hood and third was Vice Admiral Francis Samuel Drake. As was the convention of the day the fleet was split into three sections: Rodney had individual control as Admiral of the White of 12 ships flying the White Ensign; Drake had command of 12 ships flying the Blue Ensign as Admiral of the Blue; Hood was Admiral of the Red with 12 ships flying the Red Ensign.[18]

The Formidable was accompanied by three 98-gun ships: HMS Barfleur (commanded by Hood), HMS Prince George and HMS Duke plus the 90-gun HMS Namur. The remaining 31 ships ranged from 64-gun to 74-gun. In total the British fleet had 2620 guns compared to the French total of 2526. Most of the British fleet was equipped with carronades on the upper decks, which had a major advantage of flexibility, and were a great advantage at close quarters.[18]

In March 1782, Formidable was stationed at Gros Islet Bay between the island of St. Lucia in the West Indies and Pigeon Island. It was under the command of Admiral Admiral Rodney, serving as his flagship at the head of 36 ship of the line. Meanwhile the French admiral, De Grasse, headed 34 ship of the line at Fort Royal Bay in Martinique. Rodney had been dispatched from Britain with 12 well-fitted ships to rescue the West Indies from a series of attacks from the French which had already resulted in the loss of several islands. They joined 24 ships on St Lucia which had already seen action against the French and were undergoing repairs.[18]

The French had allies in the Spanish, who had 13 ship of the line at Cape Haitien in San Domingo. Together with transport ships the Spanish had a considerable force of 24,000 men. They awaited the arrival of a further 10,000 French troops dispatched from Brest, under escort of five men-of-war, to further boost their strength. The plan was that de Grasse's fleet, with at least 5000 further troops, would unite with the Spanish at Cape Haitien, and from there would attack and capture the island of Jamaica with their conjoined armada of some 60 ships and some 40,000 troops.

Rodney had been in communication with De Grasse during March organising the exchange of prisoners, which were conveyed by HMS Alert under Captain Vashon. The two officers had much mutual respect. Rodney's task was to intercept the French fleet en route to Cape Haitien.

De Grasse's vice admiral at the time was Louis-Philippe de Rigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil. Third in command was Louis Antoine de Bougainville. The French flagship was the huge 104-gun Ville de Paris. The troops were under the command of the Marquis de Bouille. The French fleet was also split into three squadrons: De Grasse led the "Cornette Blanche"; Bougainville led the "Escadre Bleu"; de Vaudreuil as a second-in-command flew the mixed blue and white colours of the "Blanche et Bleu".[18]

Other British commanders included Lord Robert Manners of HMS Resolution. Admiral William Cornwallis was in command of HMS Canada. HMS Monarch was under the command of Captain Reynolds. Other aristocrats present included Captain Lord Cranstoun on the Formidable. Sir Charles Douglas, a nephew of Charles Douglas, 3rd Duke of Queensberry, was Captain of the Fleet. Sir James Wallace was also present. Other commanders included Captains Inglefield, Parry, Dumaresq, Buckner, Graves, Blair, Burnett, Savage, Symons, Charrington, Inglis, Cornish, Truscott, Saumarez, Knight, Wilson, Williams and Wilkinson.[19]

A look-out squadron, a line of frigates headed by Captain George Anson Byron on HMS Andromache, reported all of de Grasse's movements at Fort Royal. This squadron included the speedy HMS Agamemnon and also HMS Magnificent.[20]

Pre-battle movements

| Naval Commanders |

|---|

|

On 3 April it was signalled that the repairs on the French fleet were complete. On 5 April it was reported that the French troops were boarding the ships. At 8am on Sunday 8 April it was reported that the French fleet were leaving Fort Royal. Rodney's fleet called all men to join their ships and ships began leaving Gros Islet Bay at 10.30am.[21]

The total French armada comprised 35 ship of the line, 10 frigates, and over 100 smaller ships. The smaller ships moved in advance of the men-of-war, heading for St Pierre.[21]

Just past 4pm HMS Barfleur (under Hood) at the head of the British fleet espied 5 sails ahead which she presumed to be part of the French fleet. These came into view of the Formidable around two hours later, just before sunset. They pursued the French through the night. At 2am on 9 April HMS St Albans dropped alongside Formidable, reporting that she, along with HMS Valiant, had located the French fleet in the darkness. Rodney rested for the remainder of the night.

The sun rose at 5.30am. The French fleet extended from 6 miles to 12 miles distant, navigating the waters between Dominica and Guadeloupe. The majority of the warships lay off Prince Rupert's Bay.

Due to a dead calm from 3am until 7am neither fleet could move. The initial wind only reached the Barfleur and its eight support ships, causing it to detach ahead of the main fleet, which lay in the lee of Dominica. De Grasse saw the opportunity to cripple this advanced section and wheeled to begin the first attack.

Battle

On 9 April 1782, the copper-sheathed British fleet caught up with the French, who were surprised by their speed. Admiral de Grasse ordered the French convoy to head into Guadeloupe for repair, forcing him to escort two fifty-gun ships (Fier and Experiment), and placing his fleet in line of battle in order to cover the retreat.[22]

First encounters

Hood's section of the fleet, headed by HMS Barfleur, braced for the first attack. HMS Alfred taunted the 18 French ships under de Vaudreuil which approached, as the first action, by exposing her broadside to the approaching French but without consequence. The British patiently awaited the formal signal from Rodney on the Formidable, some six miles behind, and eventually received a red flag signal telling them to "engage the enemy". As the wind rose around noon, it enabled most of the French fleet and part of the British fleet (including Rodney in the Formidable) joined the melee. At this point the French outnumbered the British two to one.[23] Captain William Bayne on the Alfred was killed during this action.[24]

After an inconclusive encounter in which both sides suffered damage, Grasse realised that the remainder of the British fleet would soon be upon them. He broke off the engagement to withdraw a safe distance.[15] Grasse moved his ships to the Saintes islands to the north (south of Gaudeloupe. Meanwhile Rodney reversed the order of his line to bring Drake's thus far undamaged ships to the front, and allow Hood to undertake repairs in the rear lines.[25]

On 10 April the French began 10 miles distant but did not turn to engage, but instead continued on their original course. By nightfall that increased their separation to 15 miles. This appears partly due to a wrong presumption on Rodney's part that the French were going to turn to engage.[25]

On Wednesday 11 April two French ships (the Zélé and the Magnanime) which had accidentally collided, and had fallen behind the main French fleet, came into view around noon. Rodney decided that attacking these two ships would cause de Grasse to return to protect them. This tactic worked and a large section of the French fleet turned to protect the pair. These movements were done without any physical attacks.[25]

Main engagement

On 12 April, the French were ranged from 6 miles to 12 miles distant and were not in formation, as the two fleets manoeuvred between the northern end of Dominica and the Saintes, in what is known as the Saintes Passage. The unfortunate Zélé had had a second collision during the night with one of its rescuers, the Ville de Paris. It was now being towed to Basse Terre in Guadeloupe by Astrée (with General de Bouille on board. They was chased by four British ships: Monarch, Valiant, Centaur and Belliqueux. De Grasse made for Guadeloupe and bore up with his fleet to protect the ship and at the same time Rodney recalled his chasing ships and made the signal for line of battle.[26]

Rear-Admiral Hood's van division were still making repairs from the action three days earlier, so he directed his rear division, under Rear Admiral Francis S. Drake, to take the lead. At 7:40, HMS Marlborough, under Captain Taylor Penny, led the British line and opened battle when he approached the centre of the French line.[17] Having remained parallel with the French, the ships of Drake's division passed the remaining length of de Grasse's line and the two sides exchanged broadsides, a typical naval engagement of this time.[15]

Initial attack

HMS Marlborough under Captain Taylor Penny of Dorset headed the British attack.[27] As the battle progressed, the strong winds of the previous day and night began to temper and became more variable. As the French line passed down the British line, the sudden shift of wind let Rodney's flagship HMS Formidable and several other ships, including HMS Duke and HMS Bedford, sail toward the French line.[28]

At 8 am, Formidable raised the red flag to permit the Marlborough to open fire and engage the French. At this point the Marlborough was opposite the Dauphin Royal who received her full broadside.[27] Sixteen ships in line separated the Marlborough from the Formidable and each stood 200 metres apart. As each circled passed the French they fired a broadside against the French. Second, behind Marlborough was HMS Arrogant which had been recently re-equipped, managed three broadsides against one from the French as they passed. Third in line was HMS Alcide under Captain Charles Thomson. Then followed HMS Nonsuch under Captain Truscott then HMS Conqueror under Captain George Balfour.[27]

Next in line was Admiral Drake on HMS Princessa who was in command of the first twelve vessels and was followed by HMS Prince George under Captain Williams. Then came the hundred year old HMS Torbay under Captain Keppel and the year-old HMS Anson under Captain William Blair, who being on the main deck was struck by round shot at waist level and horrifically sliced in two. The blue squadron was then completed by HMS Fame and HMS Russell under Captain James Saumarez.[29]

The white squadron under Rodney followed in exact formation after the blue. This was headed by HMS America under Captain Thompson. HMS Hercules under Captain Henry Savage followed. Then came HMS Prothee under Captain Buckner and HMS Resolution under Captain Robert Manners. The 24-year-old Manners was the first casualty on his ship, and was severely injured in both legs and right arm and later died of these wounds.[30] Resolution was followed by HMS Duke under Captain Alan Gardner.[30]

As Formidable was in the centre of the British line it took her almost an hour to reach the centre of the action. All ships had to maintain a steady speed and a she passed de Grasse's flagship, Ville de Paris of 104 guns the two met for the first time. The Ville de Paris was already damaged by the fifteen ships ahead of Formidable in the line. Although it was a sunny day the smoke of the battle was like a dense fog.[31] Formidable entered the smoke and approached the Ville de Paris at 8.40am.[32]

The counter movement of the fleets brought a series of ships opposite the Formidable in sequence behind the Ville de Paris, the movements bringing about a different pairing of enemies every five minutes. Next was Couronne, followed by Éveillé under Le Gardeur de Tilly then the Sceptre under the command of de Vaudreuil.[32]

Breaking the line

Within an hour, the wind had shifted to the south, forcing the French line to separate and bear to the west, as it could not hold its course into the wind. This allowed the British to use their guns on both sides of their ships without any fear of return fire from the front and rear of the French ships they were passing between. The effect was greater with the use of carronades, with which the British had just equipped nearly half their fleet; this relatively new short-range weapon was quicker to reload and more of them could be carried. Glorieux moving in the wake of the Ville de Paris under command of Captain D'Escars was the next victim; virtually a sitting duck due to damage in the previous ten minutes from HMS Duke, she was quickly pounded and dismasted by intense fire. In the confusion, four French ships beginning with Diadem broke out of sequence (partly due to the uncontrollable speed of the mastless Glorieux). Formidable turned to starboard and brought her port guns to bear on them.[15] As a result, Formidable sailed through the gap, breaking the French line. This breach was further followed through by five other British ships.[26] The breach was later recorded by Charles Dashwood who was a midshipman on the Formidable on the day.[33]

Although the concept of "breaking the line" was born here, the concept is logically of mixed blessings, since in breaking the enemy line, one breaks one's own line. Whilst the movement has the advantage that guns can be fired on both port and starboard sides, it also exposes the ship to attack on both sides. The advantage in this instance was that many of the French gunners left their post, in fear of the Formidables three tiers of guns bearing down on them.[34]

The Diadem appears to have fully withdrawn from the battle at this stage, and many presumed her to be sunk. The Formidable was followed by HMS Namur under Captain Fanshawe, then HMS St Albans under Captain Inglis. These were followed by the deadly HMS Canada under Captain William Cornwallis, HMS Repulse under Captain Thomas Dumaresq, and HMS Ajax under Captain Nicholas Charrington. Each of these fired further upon the hapless and already crippled Glorieux.[35]

Simultaneously, by accident of the smoke, Commodore Edmund Affleck on HMS Bedford, the hindmost ship of the central white squadron, accidentally sailed through the confused French line, between Cesar and Hector, only discovering this error when no enemy lay on his starboard side in the clearing smoke.[36]

The Bedford was followed by Hood's red squadron and this broke the French line into three sections. In the confusion the two leading ships of the rear red squadron, HMS Prince William and HMS Magnificent had somehow passed the Bedford, who was now third in line within the red squadron, completely detached from its own white squadron.[36] The whole red squadron then passed between Cesar and Hector, causing each to be crippled. The final ship of the red squadron, HMS Royal Oak, passed the stern of the Cesar and delivered a final blow a few minutes after 11am. Both fleets then drifted apart for some time and became temporarily becalmed.[36]

Around noon, to the horror of both fleets, it was spotted that the waters were teaming with sharks attracted by the noise and blood. French casualties were greatly increased due to the high number of troops packed onto the lower decks: a minimum of 900 per ship and no less than 1300 on the Ville de Paris. In order to lessen the confusion the French had been throwing the dead (and perhaps the near dead) overboard, and this was a rich feast for the sharks.[36]

French retreat

The French now lay totally to the leeward of the British fleet and the fleet stood between them and their destination. They had little option on the re-emergence of the wind but to sail west with the wind, and try to escape. At 1pm the frigate Richemont, under command of Captain De Mortemart but with Denis Decrès in charge of the marines, was sent to join a towing cable to the heavily crippled Glorieux. Souverain moved alongside to provide covering fire. However the British, with both wind and cannon-power in their favour, moved a number of ships up to block this movement. The captain of the Glorieux was already dead, and she was under command of the senior officer remaining: Lieutenant Trogoff de Kerlessi. Souverain and Richmond retreated under heavy fire and Kerlessi had little option but to tear the flag from the mast and surrender, which was done to the Royal Oak. Captain Burnett used this opportunity to restock his depleted powder supplies. Meanwhile HMS Monarch stood alongside HMS Andromache who was acting as a supply ship to the British fleet, and forty barrels of powder were exchanged.[37]

In the next action, around 1.30, HMS Centaur and HMS Bedford attacked the stricken César, captained by Bernard de Marigny. Marigny refused to surrender and was seriously wounded in the first five minutes. Command then fell to his captain, Captain Paul.[37]

With their formation shattered and many of their ships severely damaged, the French fell away to the southwest in small groups.[15] Rodney attempted to redeploy and make repairs before pursuing the French.[5] By 2pm, the wind had freshened and a general chase ensued. As the British pressed south, Ardent. After taking possession of Glorieux they caught up with the French rear at around 3pm. Admiral de Grasse signalled other ships to protect the Ville de Paris, but this was only partially fulfilled. Nine ships from de Vaudreuil's squadron came to his aid. The British fleet bore down on this small group. In succession, Rodney's ships isolated the other three ships. César, which was soon totally dismasted and in flames, was captured by Centaur.[38] Soon after 5pm the Hector having been flanked by HMS Canada and HMS Alcide and soon became a complete dismasted wreck. Following the mortal wounding of its captain, De la Vicomte, his first lieutenant De Beaumanoir, lowered the ship's flag and surrendered to the Alcide.[39]

Louis Antoine de Bougainville, who commanded Auguste, had ordered eight ships of his own division[15] to aid Ville de Paris but only the Ardent had proceeded and its isolation caused it to be flanked by HMS Belliqueux and HMS Prince William and this soon led to its capture.[39]

At 5.30 pm, de Grasse with Ville de Paris, stood practically alone and had Barfleur in close pursuit, and Formidable close behind. Five ships from de Vaudreuil's squadron were trying to protect her, but none in close formation. These were Triumphante (Vaudreuil's flagship), Bourgogne (under De La Charette), Magnifique (Macarty Macteigne), Pluton (De Rion) and Marseillais (De Castellane-Majastre). Three ships from De Grasse's squadron also still remained: Languedoc, Couronne and Sceptre.[40]

De Grasse's closest protector the Couronne, moved away at the approach of HMS Canada, which began the final attack on the Ville de Paris. With little support and suffering huge losses in men, made another attempt to signal the fleet and gave the order "to build the line on the starboard tack", but again this was not done.[41] By this time, most of the French fleet, apart from those ships that were surrounded, had retreated.

End of the battle

HMS Canada swept passed the Ville de Paris doing damage to the spars and slowing her further. HMS Russell under Captain Saumarez then moved diagonally along the stern of the flagship and fired a broadside which ripped the entire length of the ship. The Russell then moved to the leeward side to hamper the ship's retreat, whilst HMS Barfleur moved onto the opposite side. The Languedoc attempted to approach to give aid but was beaten back by HMS Duke.[42]

The Ville de Paris was in desperate condition with all masts damaged and the rudder shot away. At least 300 men were dead or injured in the cockpit. Around 6pm, being overwhelmed and suffering terrible losses, the Ville de Paris eventually struck her colours, signalling surrender.[43] Hood approached on the Barfleur, which de Grasse had indicated was his preferred method of surrender. In an ungentlemanly act Hood ordered one final broadside at close quarters, when de Grasse had already indicated surrender.[42]

The boarding crew, which included the British fleet surgeon Gilbert Blane, were horrified at the carnage;[lower-alpha 1] Remarkably Admiral de Grasse appeared not to have a scratch on him, whilst every one of his officers had either been killed or wounded. Only three men were unwounded. Rodney boarded soon after, and Hood presented Grasse to him.[15] With his surrender, the battle had effectively ended, except for a few long-range desultory shots and the retreat of many of the French ships in disorder.[41] The gallantry of William Cornwallis of HMS Canada and younger brother of Charles Cornwallis gained the admiration of the whole fleet, one officer noted that he like Hector, as if emulous to revenge his brothers cause.[45]

The Comte de Vaudreuil in Sceptre, seeing Grasse's fate through his telescope, took command of the remaining scattered French naval fleet. On 13 April, he had ten ships with him and sailed toward Cap-Français.[15] Rodney signalled his fleet not to pursue the remaining ships. The battle was therefore over.[46]

Later that night, around 9pm, a fire begun by the entrapped French crew on the lower decks, breaking into the liquor store. By 10.30pm, and now out of control, the magazine aboard the César exploded, killing more than 400 French and 58 British sailors, plus the lieutenant in charge, all from HMS Centaur, although many men jumped overboard trying to avoid the disaster.[47] Those jumping overboard met a more horrible fate, due to the sharks below. Captain Marigny, who was confined to his cabin, was one of the many killed. None of the British prize crew survived.[48]

.jpg) A 1785 engraving of de Grasse surrendering to Rodney.

A 1785 engraving of de Grasse surrendering to Rodney.- The end of the César, by François Aimé Louis Dumoulin

Captued French ships after the battle by Dominic Serres

Captued French ships after the battle by Dominic Serres

Casualties

The British lost 243 killed and 816 wounded, and two captains of 36 were killed, whilst no ships were lost. The highest casualties were on HMS Duke with 73 killed or wounded.[49] The total French casualties have never been stated, but six captains out of 30 were killed. In terms of soldiers and sailors however, estimates range from 3,000 killed or wounded and 5,000 captured[50], to as many as around 3,000 dead, 6,000 wounded[51] and 6,000 captured.[52] In addition to several French ships captured, others were severely damaged. The high number of men demonstrates the considerable force the French committed to achieve the invasion of Jamaica.[49] Of the Ville de Paris' crew alone, over 400 were killed and more than 700 were wounded – more than the casualties of the entire British fleet.[4] De Grasse captured after the battle was sent to England where he was paroled - he was the first French admiral in history to be captured by an enemy.

Aftermath

Rodney's failure to follow up the victory by a pursuit was criticised. Samuel Hood said that the twenty French ships would have been captured had Rodney maintained the chase. In 1899 the Navy Records Society published the Dispatches and Letters Relating to the Blockading of Brest. In the introduction, they include a small biography of William Cornwallis. A poem purportedly written by him includes the lines:

Had a chief worthy Britain commanded our fleet,

Twenty-five good French ships had been laid at our feet.[53]

On 17 April, Hood was sent in pursuit of the French, and promptly captured two 64-gun ships of the line (Jason and Caton) and two smaller warships in the Battle of the Mona Passage on 19 April.[5] Following this victory Hood rendezvoused with Rodney at Port Royal on 29 April. As a result of the damage the fleet had sustained in battle, repairs took nine weeks.[54]

Soon after the defeat, the French fleet reached Cap Francois in several waves; the main contingent, under Vaudreuil, arrived on 25 April; Marseillois, along with Hercule, Pluton and Éveillé, arrived on 11 May.[55] In May, all French ships from the battle arrived from Martinique, then numbering twenty-six ships, and were soon joined by twelve Spanish ships. Disease took a hold of the French forces, in particular the soldiers, of whom thousands died. The allies hesitation and indecision soon led to the abandonment of the attack on Jamaica.[15] Jamaica remained a British colony, as indeed did Barbados, St Lucia and Antigua.[4]

Disaster struck months after the battle when Admiral Graves was leading a fleet back to England which included the French prizes from the battle. The fleet encountered the 1782 Central Atlantic hurricane in September which hit off Newfoundland. The Glorieux, Hector and Ville De Paris along with other ships foundered or sunk with heavy loss of life.[56]

Reactions

News of the battle reached France in June and was met with despair. The defeat along with the loss of the Ville de Paris was a devastating blow to French King Louis XVI.[57] The navy minister the Marquis de Castries greeted the news as 'a grim disaster'.[58] The Comte De Vergennes felt undermined in the confidence of the French navy.[59] All blame lay on the Comte De Grasse, whilst he himself sought long to clear his name. He blamed his subordinates, Vaudreuil and Bougainville for the defeat, but an infuriated Louis bluntly told De Grasse to retire.[60] The battle had repercussions for France's finances - the monetary loss was huge; on the Ville de Paris alone 36 chests of money worth at least £500,000 were found; this being payment for the troops.[61] During the first four years of the war the French navy had lost four ships of the line, three of them to accidents, whereas during 1782 it would lose fifteen of the line (nearly half of these being in April alone).[62] The losses of these ships were significant - Louis nevertheless promised to build more ships after new taxes were levied.[57] The French finance minister Jean-François Joly de Fleury successfully secured the addition of a Vingtième income tax - the third and last one of its kind in the ancien regime.[63]

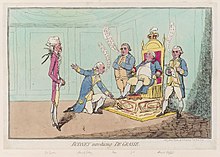

In Britain there was widespread celebration as they greeted news of the victory. In the newspaper 'Cumberland Pacquet' it was noted, a joy unknown for years past seemed to spread itself amongst all ranks of people.[64] On his return Rodney was feted as a hero, a number of cartoons and caricatures were created to commemorate the victory. He presented the Comte De Grasse personally to King George III as a prisoner, and was created a peer with £2,000 a year settled on the title in perpetuity. A number of paintings were commissioned to celebrate his victory notably by Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds. Hood was also elevated to the peerage, while Drake and Affleck were made baronets.[65]

Impact on peace negotiations

Following the Franco-American victory at Yorktown six months earlier and the change of Government in England, peace negotiations in Paris had begun among Britain, the American colonies, France, and Spain in early 1782. The battle had a significant effect on those talks when news arrived of its outcome in June.[7] The result of the Saintes transferred the strategic initiative to the British whose dominance at sea was reasserted. News of the defeat reached the Americans who soon realised they were unlikely to have much French support in the future - American General Nathaniel Greene had high hopes of French assistance in the recapture of Charleston but the defeat led to its abandonment.[66]

The British no longer humbled stiffened their resolve; they objected to American claims on the Newfoundland fisheries and Canada. As a result the American negotiators led by John Jay became more amenable.[67] Not only did they drop their minimum demands and insisted on the single precondition of recognition of their Independence, they also put forward America's abandonment of its commitment to make no separate peace treaty without the French. The victory at the Saintes thus signalled a collapse in the Franco-American alliance.[67] Despite this the battle did not affect the overall outcome of the American Revolution.[68]

De Castries urged Spain to join the French to send another armada against the British West Indies. On the theory of this victory it would win bargaining power to force Britain's acceptance of American Independence.[69] Vergennes however was desperate for peace, and time was running out - France was approaching the limits of its ability to borrow money.[59] France had also promised not to make peace with England until Spain had conquered their main war aim Gibraltar. By October this attempt had been defeated; a huge Spanish attempt in September was repelled with heavy losses, following which Richard Howe with a large naval convoy then relieved the garrison. Vergnnes as a result demanded that Spain give up its claim on Gibraltar to make peace which the latter acquiesced to.[70] The Comte De Grasse who was a high profile prisoner in Britain was used to bring back and forth messages of peace between Great Britain and France.[71] A preliminary peace treaty between Great Britain and America was signed on 30 November; thus with the Americans split from their allies peace was signed with France and Spain in January 1783. Initial articles of peace were signed in July, with a full treaty following in September 1783. Owing to the military successes in 1782 the peace treaties that brought the war to an end were less disadvantageous for Britain than had been anticipated.[64]

Impact on naval tactics

The battle is famous for the innovative British tactic of "breaking the line", in which the British ships passed through a gap in the French line, engaging the enemy from leeward and throwing them into disorder.[6] Arguably the battle was not the first time a line had been broken; Dano–Norwegian admiral Niels Juel did this in the Battle of Køge Bay more than a hundred years earlier and even earlier the Dutch admiral Michiel de Ruyter used it for the first time in the last day of the Four Days' Battle in 1666 (and again in the Battle of Schooneveld and the Battle of Texel of 1673). Historians disagree about whether the tactic was intentional or made possible by weather. And, if intentional, who should receive credit: Rodney[lower-alpha 2], his Scottish Captain-of-the-Fleet and aide-de-camp Sir Charles Douglas [lower-alpha 3] or John Clerk of Eldin[8]

As a result of the battle, British naval tactics changed. The old method involved the attacking fleet spreading itself along the entire enemy line. In the five formal fleet actions involving the Royal Navy between the Battle of the Saintes and Trafalgar, all were victories for the British, which were achieved by the creation of localised numerical superiority.[73]

Monuments

A huge ornate monument to the three captains lost in the battle - William Blair, William Bayne and Robert Manners - was erected to their memory in Westminster Abbey.[74]

A memorial to Admiral Rodney was created to honour the battle in Spanish Town, Jamaica. It was created by the sculptor John Bacon in 1801. Two of the VIle de Paris guns flank Rodney's statue.[75]

The 'three captains memorial' design that would lay in Westminster Abby

The 'three captains memorial' design that would lay in Westminster Abby Rodney monument in Spanish Town, Jamaica

Rodney monument in Spanish Town, Jamaica

Order of battle

Britain

| Admiral Sir George Rodney's fleet | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van | ||||||||

| Ship | Rate | Guns | Commander | Casualties | Notes | |||

| Killed | Wounded | Total | ||||||

| HMS Royal Oak | Third rate | 74 | Captain Thomas Burnett | 8 |

30 |

38 |

||

| HMS Alfred | Third rate | 74 | Captain William Bayne † | 12 |

40 |

52 |

Bayne killed on 9 April | |

| HMS Montagu | Third rate | 74 | Captain George Bowen | 14 |

29 |

43 |

||

| HMS Yarmouth | Third rate | 64 | Captain Anthony Parrey | 14 |

33 |

47 |

||

| HMS Valiant | Third rate | 74 | Captain Samuel Granston Goodall | 10 |

28 |

38 |

||

| HMS Barfleur | Second rate | 98 | Rear-Admiral Sir Samuel Hood Captain John Knight |

10 |

37 |

47 |

Flagship of van | |

| HMS Monarch | Third rate | 74 | Captain Francis Reynolds | 16 |

33 |

49 |

||

| HMS Warrior | Third rate | 74 | Captain Sir James Wallace | 5 |

21 |

26 |

||

| HMS Belliqueux | Third rate | 64 | Captain Andrew Sutherland (mariner) | 4 |

10 |

14 |

||

| HMS Centaur | Third rate | 74 | Captain John Nicholson Inglefield | ? |

? |

? |

No casualty returns made | |

| HMS Magnificent | Third rate | 74 | Captain Robert Linzee | 6 |

11 |

17 |

||

| HMS Prince William | Third rate | 64 | Captain George Wilkinson | 0 |

0 |

0 |

||

| Centre | ||||||||

| HMS Bedford | Third rate | 74 | Commodore Edmund Affleck Captain Thomas Graves |

0 |

17 |

17 |

||

| HMS Ajax | Third rate | 74 | Captain Nicholas Charrington | 9 |

40 |

49 |

||

| HMS Repulse | Third rate | 64 | Captain Thomas Dumaresq | 3 |

11 |

14 |

||

| HMS Canada | Third rate | 74 | Captain William Cornwallis | 12 |

23 |

35 |

||

| HMS St Albans | Third rate | 64 | Captain Charles Inglis | 0 |

6 |

6 |

||

| HMS Namur | Second rate | 90 | Captain Robert Fanshawe | 6 |

25 |

31 |

||

| HMS Formidable | Second rate | 98 | Admiral Sir George Rodney Captain Sir Charles Douglas 2nd Captain Charles Symons |

15 |

39 |

53 |

Flagship of centre | |

| HMS Duke | Second rate | 98 | Captain Alan Gardner | 13 |

60 |

73 |

||

| HMS Agamemnon | Third rate | 64 | Captain Benjamin Caldwell | 15 |

23 |

38 |

||

| HMS Resolution | Third rate | 74 | Captain Lord Robert Manners | 4 |

34 |

38 |

||

| HMS Prothee | Third rate | 64 | Captain Charles Buckner | 5 |

25 |

30 |

||

| HMS Hercules | Third rate | 74 | Captain Henry Savage | 6 |

19 |

25 |

Captain Savage wounded | |

| HMS America | Third rate | 64 | Captain Samuel Thompson | 1 |

1 |

2 |

||

| Rear | ||||||||

| HMS Russell | Third rate | 74 | Captain James Saumarez | 10 |

29 |

39 |

||

| HMS Fame | Third rate | 74 | Captain Robert Barbor | 3 |

12 |

15 |

||

| HMS Anson | Third rate | 64 | Captain William Blair † | 3 |

13 |

16 |

||

| HMS Torbay | Third rate | 74 | Captain John Lewis Gidoin | 10 |

25 |

35 |

||

| HMS Prince George | Second rate | 98 | Captain James Williams | 9 |

24 |

33 |

||

| HMS Princessa | Third rate | 70 | Rear-Admiral Francis Samuel Drake Captain Charles Knatchbull |

3 |

22 |

25 |

Flagship of rear | |

| HMS Conqueror | Third rate | 74 | Captain George Balfour | 7 |

23 |

30 |

||

| HMS Nonsuch | Third rate | 64 | Captain William Truscott | 3 |

3 |

6 |

||

| HMS Alcide | Third rate | 74 | Captain Charles Thompson | ? |

? |

? |

No casualty returns made | |

| HMS Arrogant | Third rate | 74 | Captain Samuel Pitchford Cornish | 0 |

0 |

0 |

||

| HMS Marlborough | Third rate | 74 | Captain Taylor Penny | 3 |

16 |

19 |

||

| Total recorded casualties: 239 killed, 762 wounded (casualties for two ships unknown) | ||||||||

| Source: The London Gazette, 12 December 1782.[76] | ||||||||

France

Not in line: frigates Richemont (Mortemart, Amazone (Ensign Bourgarel de Martignan, acting captain replacing Montguyot), Aimable (Lieutenant de Suzannet), Galathée (Lieutenant de Roquart); corvette Cérès (Lieutenant de Paroy); cutter Clairvoyant (Ensign de Daché);[102][103] cutter Pandour (Grasse-Limermont).[104]

In popular culture

The battle is the subject of the title track on No Grave But the Sea, the 2017 album by the Scottish "pirate metal" band Alestorm. The lyrics mention De Grasse, the British ships HMS Duke and Bedford, and the tactic of "breaking the line".[105]

The battle was the climax of the first written Richard Bolitho novel by Alexander Kent.

The battle is featured in 'Le Dernier Panache', a show in the Puy du Fou; where the show's main character, François de Charette, fights in the Battle of the Saintes. In the show and in reality he fought the battle as a lieutenant de vaisseau.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of the Saintes. |

Footnotes

- Blane noted, "When boarded, Ville de Paris presented a scene of complete horror. The numbers killed were so great that the surviving, either from want of leisure, or through dismay, had not thrown the bodies of the killed overboard, so that the decks were covered with the blood and mangled limbs of the dead, as well as the wounded and dying".[44]

- According to dramatist Richard Cumberland, Rodney discussed breaking the line over dinner at Lord George Germain's country residence at Stoneland. He used cherry stones to represent two battle lines and declared to pierce the enemy's fleet.[6]

- Charles Dashwood a seventeen-year-old aide-de-camp to both men, wrote, "Sir Charles was (heading to Sir George's cabin when he) met with Rodney, who was coming from the cabin … Sir Charles bowed and said: ‘Sir George, I give you the joy of victory!’ ‘Poh!’ said Rodney ‘the day is not half won yet.’ ‘Break the line, Sir George!’ said your father, ‘the day is your own, and I shall insure you the victory.’ ‘No’ said the Admiral, ‘I will not break my line.’ After another request and refusal, Sir Charles ordered the helmsman to put to port; Sir Rodney countermanded the order and said, ‘starboard.’ He then said, ‘Remember, Sir Charles that I am Commander-in Chief – starboard, sir (to the helmsman).’ A couple of minutes later, Sir Charles addressed him again – ‘only break the line Sir George, and the day is your own.’ Rodney then said, ‘Well, well, do as you like,’ turned around, and walked into the aft cabin. I was then ordered below to give necessary directions for opening the fire on the larboard side. On my return to the quarterdeck (from below), I found the Formidable passing between two French ships, each nearly touching us.[72]

Citations

- Wallenfeldt 2009, p. 78.

- Black 1999, p. 141.

- Greene 2005, p. xviibut the British Navy emerged from the siege of Yorktown intact, allowing Admiral Sir George Bridges Rodney to score a decisive victory over de Grasse in the Battle of the Saintes

- Valin 2009, p. 58.

- Gardiner 1996, pp. 123-127.

- O'Shaughnessy 2013, p. 314.

- Allison & Ferreiro 2018, p. 220:this reversal had a significant effect on peace negotiations to end the American revolution which were already underway and would lead to an agreement by the end of year

- Valin 2009, pp. 67-68.

- Dull 1975, p. 244.

- Dull 1975, pp. 248-9.

- O'Shaughnessy 2013, p. 208.

- Rogoziński 1999, p. 115.

- Trew 2006, pp. 154-55.

- Dull 1975, p. 282.

- Trew 2006, pp. 157-62.

- Mahan 2020, pp. 205−226.

- Lavery 2009, pp. 144-45.

- Fraser 1904, p. 102.

- Fraser 1904, p. 72.

- Fraser 1904, p. 79.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 80-81.

- & Stevens 2009, p. 173.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 86-89.

- Fraser 1904, p. 111.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 90-92.

- Mahan 2020, pp. 194−221.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 103-05.

- Tunstall 2001, p. 308.

- Fraser 1904, p. 107.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 110-11.

- Fraser 1904, p. 113.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 117-19.

- Fraser 1904, p. 123.

- Fraser 1904, p. 126.

- Fraser 1904, p. 122.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 130-33.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 137-38.

- Roche 2005, p. 238.

- Fraser 1904, p. 140.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 143-44.

- Mahan 2020, pp. 205-26.

- Fraser 1904, pp. 146-48.

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1867). Batailles navales de la France (in French). 2. Challamel ainé. p. 155.

- Macintyre, Donald (1962). Admiral Rodney. Norton. p. 239.

- Stedman, Charles (1794). The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War: who Served Under Sir W. Howe, Sir H. Clinton, and the Marquis Cornwallis. P. Wogan, P. Byrne, J. Moore, and W. Jones. p. 433.

- Fraser 1904, p. 152.

- Gardiner 1996, pp. 123-27.

- Fraser 1904, p. 155.

- Mahan 2020, p. 220.

- Trew 2006, p. 169.

- Lendrum, John (1836). History of the American Revolution: With a Summary Review of the State and Character of the British Colonies of North America, Volume 2. J. and B. Williams. p. 173.

- Duffy & Mackay 2009, p. 146.

- Leyland, John (1899). Dispatches and letters relating to the blockade of Brest, 1803–1805. Printed for the Navy Records Society. p. xx.

- Fraser 1904, p. 163.

- Troude 1867, p. 158.

- Fraser 1904, p. 164.

- Hardman 2016, p. 169.

- Tombs & Tombs 2010, p. 178.

- Greene & Pole 2008, p. 358.

- Greene 2005, p. 328.

- Fraser 1904, p. 158.

- Dull 2009, p. 115.

- Hardman 2016, pp. 173, 218-19.

- Page 2014, p. 38.

- Mahan 2020, pp. 194-221.

- Buchanan 2019, p. 307.

- Harvey 2004, pp. 530-31.

- Barnes 2014, p. 135.

- Miller 2015, p. 236.

- Mahan 2020, pp. 205-226.

- Greene & Pole 2008, p. 359.

- "Rodney's Battle of 12 April 1782: A Statement of Some Important Facts, Supported by Authentic Documents, Relating to the Operation of Breaking the Enemy's Line, as Practiced for the First Time in the Celebrated Battle of 12 April 1782". Quarterly Review. XLII (LXXXIII): 64. 1830.

- Willis, Sam (2008). Fighting at Sea in the Eighteenth Century: The Art of Sailing Warfare. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978 1 84383 367 3.

- Famous Fighters of the Fleet, Edward Fraser, 1904, p.111

- Aspinall, Algernon E (1907). The pocket guide to the West Indies, British Guiana, British Honduras, the Bermudas, the Spanish Main, and the Panama canal (New and revised 1914 ed.). Rand, McNally & Company. pp. 188–189. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "No. 12396". The London Gazette. 12 October 1782. pp. 3–4.

- Troude (1867), p. 140.

- Lacour-Gayet (1905), p. 648.

- Guérin (1863), p. 148.

- Gardiner (1905), p. 143.

- Guérin (1863), p. 149.

- Contenson (1934), p. 150.

- Contenson (1934), p. 185.

- Vergé-Franceschi (2002), p. 45.

- Contenson (1934), p. 270-271.

- Marley (1998), p. 522.

- Contenson (1934), p. 221.

- Contenson (1934), p. 277.

- Contenson (1934), p. 276.

- Etat nominatif des pensions sur le trésor royal, troisième classe, en annexe de la séance du 21 avril 1790. 1882. p. 488. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Gardiner (1905), p. 142.

- Contenson (1934), p. 193.

- Contenson (1934), p. 228.

- Contenson (1934), p. 219.

- Contenson (1934), p. 211.

- Contenson (1934), p. 222.

- Contenson (1934), p. 199.

- Contenson (1934), p. 241.

- Contenson (1934), p. 155.

- Gardiner (1905), p. 127.

- Troude (1867), p. 141.

- Marley (1998), p. 141.

- Contenson (1934), p. 187.

- "Alestorm – No Grave but the Sea". Song Meanings.

Bibliography

- Allison, David K; Ferreiro, Larrie D, eds. (2018). The American Revolution: A World War. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 9781588346599.

- Barnes, Ian (2014). The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution. Routledge. ISBN 9781136752711.

- Black, Jeremy (1999). Warfare in the Eighteenth Century. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35245-6.

- Buchanan, John (2019). The Road to Charleston: Nathanael Greene and the American Revolution. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 9780813942254.

- Douglas, Major-General Sir Howard; Christopher J. Valin (2010). Naval Evolutions: A Memoir. Fireship Press. ISBN 1-935585-27-4.

- Duffy, Michael; Mackay, Ruddock F (2009). Hawke, Nelson and British Naval Leadership, 1747-1805. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843834991.

- Dull, Jonathan R. (1975). The French Navy and American Independence: A Study of Arms and Diplomacy, 1774–1787. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691069203.

- Dull, Jonathan R (2009). The Age of the Ship of the Line: The British & French Navies, 1650–1815. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781473811669.

- Contenson, Ludovic (1934). La Société des Cincinnati de France et la guerre d'Amérique (1778-1783). Paris: éditions Auguste Picard. OCLC 7842336.

- Fraser, Edward (1904). Famous Fighters of the Fleet: Glimpses Through the Cannon Smoke in the Days of the Old Navy. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 9781104820039.

- Fullom, Stephen Watson (1865). Life of General Sir Howard Douglas, Bart.

- Gardiner, Asa Bird (1905). The order of the Cincinnati in France. The Rhode Island state society of Cincinnati. OCLC 5104049.

- Gardiner, Robert (1996). Navies and the American Revolution 1775-1783. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781557506238.

- Guérin, Léon (1863). Histoire maritime de France (in French). 5. Dufour et Mulat.

- Greene, Jerome (2005). The Guns of Independence: The Siege of Yorktown, 1781. Savas Beatie. ISBN 9781611210057.

- Greene, Jack P; Pole, J.R, eds. (2008). A Companion to the American Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780470756447.

- Hardman, John (2016). The Life of Louis XVI. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300220421.

- Harvey, Robert (2004). A Few Bloody Noses: The American Revolutionary War. Robinson. ISBN 9781841199528.

- Lacour-Gayet, Georges (1905). La marine militaire de la France sous le règne de Louis XVI. Paris: Honoré Champion. OCLC 763372623.

- Lavery, Brian (2009). Empire of the seas: how the navy forged the modern world. Conway. ISBN 9781844861095.

- Mahan, Alfred Thayer (2020). The Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486842103.

- Marley, David (1998). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the New World, 1492 to the Present. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0874368375.

- Miller, Donald (2015). Lafayette: His Extraordinary Life and Legacy. iUniverse. ISBN 9781491759974.

- Naval History Division (1964). Naval Documents of the American Revolution. United States: Government Printing Office.

- O'Shaughnessy, Andrew (2013). The Men Who Lost America: British Command during the Revolutionary War and the Preservation of the Empire. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781780742465.

- Page, Anthony (2014). Britain and the Seventy Years War, 1744-1815: Enlightenment, Revolution and Empire. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9781137474438.

- Playfair, John. "On the Naval Tactics of the Late John Clerk, Esq. of Eldin." The Works of John Playfair, Vol. III (1822)

- Rogoziński, Jan (1999). A Brief History of the Caribbean: From the Arawak and the Carib to the Present. Facts On File. ISBN 9780816038114.

- Roche, Jean-Michel (2005). Dictionnaire des bâtiments de la flotte de guerre française de Colbert à nos jours. 1. Group Retozel-Maury Millau. ISBN 978-2-9525917-0-6. OCLC 165892922.

- Stevens, William (2009). History of Sea Power; Volume 95 of Historische Schiffahrt. Books on Demand. ISBN 9783861950998.

- Tombs, Isabelle; Tombs, Robert (2010). That Sweet Enemy: The British and the French from the Sun King to the Present. Random House. ISBN 9781446426234.

- Tunstall, Brian (2001). Naval Warfare in the Age of Sail: The Evolution of Fighting Tactics, 1650-1815. Wellfleet Press. ISBN 9780785814269.

- Trew, Peter (2006). Rodney and the Breaking of the Line. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 9781844151431.

- Wallenfeldt, Jeff, ed. (2009). The American Revolutionary War and The War of 1812: People, Politics, and Power America at War. Britannica Educational Publishing. ISBN 9781615300495.

- Valin, Christopher J. (2009). Fortune's Favorite: Sir Charles Douglas and the Breaking of the Line. Fireship Press. ISBN 1-934757-72-1.

- Vergé-Franceschi, Michel (2002). Dictionnaire d'Histoire maritime. Paris: Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221-08751-8. OCLC 806386640.

External links

- Hannay, David (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–44.

- Robinson, Ian M. (3 December 2009). "The Battle of the Saintes 12th April 1782". The Realm of Chance: warfare and the balance of power, 1618–1815. Retrieved 6 July 2011.