Third Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Third Amendment (Amendment III) to the United States Constitution places restrictions on the quartering of soldiers in private homes without the owner's consent, forbidding the practice in peacetime. The amendment is a response to the Quartering Acts passed by the British parliament during the buildup to the American Revolutionary War, which had allowed the British Army to lodge soldiers in private residences.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

|

| Unratified Amendments |

| History |

| Full text |

|

The Third Amendment was introduced in Congress in 1789 by James Madison as a part of the United States Bill of Rights, in response to Anti-Federalist objections to the new Constitution. Congress proposed the amendment to the states on September 28, 1789, and by December 15, 1791, the necessary three-quarters of the states had ratified it. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson announced the adoption of the amendment on March 1, 1792.

The amendment is one of the least controversial of the Constitution and is rarely litigated, with criminal justice writer Radley Balko calling it the "runt piglet" of the U.S. Constitution.[1] To date, it has never been the primary basis of a Supreme Court decision,[2][3][4] though it was the basis of the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit case Engblom v. Carey.

Text

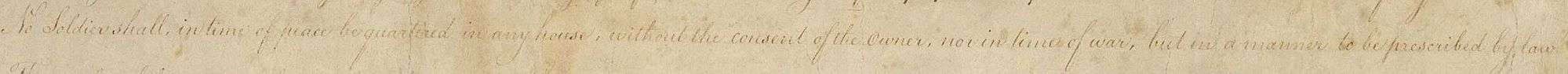

The complete text of the amendment is:

No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.[5]

Background

In 1765, the British parliament enacted the first of the Quartering Acts,[6] requiring the American colonies to pay the costs of British soldiers serving in the colonies, and requiring that if the local barracks provided insufficient space, that the colonists lodge the troops in alehouses, inns, and livery stables. After the Boston Tea Party, the Quartering Act of 1774 was enacted. As one of the Intolerable Acts that pushed the colonies toward revolution, it authorized British troops to be housed wherever necessary, including in private homes.[7] The quartering of troops was cited as one of the colonists' grievances in the United States Declaration of Independence.[3]

Adoption

After several years of comparatively weak government under the Articles of Confederation, a Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia proposed a new constitution on September 17, 1787, featuring a stronger chief executive and other changes. George Mason, a Constitutional Convention delegate and the drafter of Virginia's Declaration of Rights, proposed that a bill of rights listing and guaranteeing civil liberties be included. Other delegates—including future Bill of Rights drafter James Madison—disagreed, arguing that existing state guarantees of civil liberties were sufficient and that any attempt to enumerate individual rights risked implying that other, unnamed rights were unprotected. After a brief debate, Mason's proposal was defeated by a unanimous vote of the state delegations.[8]

For the constitution to be ratified, however, nine of the thirteen states were required to approve it in state conventions. Opposition to ratification ("Anti-Federalism") was partly based on the Constitution's lack of adequate guarantees for civil liberties. Supporters of the Constitution in states where popular sentiment was against ratification (including Virginia, Massachusetts, and New York) successfully proposed that their state conventions both ratify the Constitution and call for the addition of a bill of rights. Several state conventions specifically proposed a provision against the quartering of troops in private homes.[3] At the 1788 Virginia Ratifying Convention, Patrick Henry stated, "One of our first complaints, under the former government, was the quartering of troops among us. This was one of the principal reasons for dissolving the connection with Great Britain. Here we may have troops in time of peace. They may be billeted in any manner—to tyrannize, oppress, and crush us."[7]

Proposal and ratification

In the 1st United States Congress, following the state legislatures' request, James Madison proposed twenty constitutional amendments based on state bills of rights and English sources such as the Bill of Rights 1689; one of these was a prohibition against quartering troops in private homes. Several revisions to the future Third Amendment were proposed in Congress, which chiefly differed in the way in which peace and war were distinguished (including the possibility of a situation, such as unrest, which was neither peace nor war), and whether the executive or the legislature would have the authority to authorize quartering.[9] However, the amendment ultimately passed Congress almost unchanged and by unanimous vote.[3] Congress reduced Madison's proposed twenty amendments to twelve, and these were submitted to the states for ratification on September 25, 1789.[10]

By the time the Bill of Rights was submitted to the states for ratification, opinions had shifted in both parties. Many Federalists, who had previously opposed a Bill of Rights, now supported the Bill as a means of silencing the Anti-Federalists' most effective criticism. Many Anti-Federalists, in contrast, now opposed it, realizing the Bill's adoption would greatly lessen the chances of a second constitutional convention, which they desired.[11] Anti-Federalists such as Richard Henry Lee also argued that the Bill left the most objectionable portions of the Constitution, such as the federal judiciary and direct taxation, intact.[12]

On November 20, 1789, New Jersey ratified eleven of the twelve amendments, rejecting Article II, which regulated Congressional pay raises. On December 19 and 22, respectively, Maryland and North Carolina ratified all twelve amendments.[13] On January 19, 25, and 28, 1790, respectively, South Carolina, New Hampshire, and Delaware ratified the Bill, though New Hampshire rejected the amendment on Congressional pay raises, and Delaware rejected Article I, which regulated the size of the House.[13] This brought the total of ratifying states to six of the required ten, but the process stalled in other states: Connecticut and Georgia found a Bill of Rights unnecessary and so refused to ratify, while Massachusetts ratified most of the amendments, but failed to send official notice to the Secretary of State that it had done so.[12][lower-alpha 1]

In February through June 1790, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island ratified eleven of the amendments, though all three rejected the amendment on Congressional pay raises. Virginia initially postponed its debate, but after Vermont was admitted to the Union in 1791, the total number of states needed for ratification rose to eleven. Vermont ratified on November 3, 1791, approving all twelve amendments, and Virginia finally followed on December 15, 1791.[12] Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson announced the adoption of the ten successfully ratified amendments on March 1, 1792.[14]

Judicial interpretation

The Third Amendment is among the least cited sections of the U.S. Constitution.[15] In the words of Encyclopædia Britannica, "as the history of the country progressed with little conflict on American soil, the amendment has had little occasion to be invoked."[16] To date, no major Supreme Court decision has used the amendment as its primary basis.[3][4]

The Third Amendment has been invoked in a few instances as helping establish an implicit right to privacy in the Constitution.[17] Justice William O. Douglas used the amendment along with others in the Bill of Rights as a partial basis for the majority decision in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965),[18] which cited the Third Amendment as implying a belief that an individual's home should be free from agents of the state.[17]

In one of the seven opinions in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952), Justice Robert H. Jackson cited the Third Amendment as providing evidence of the Framers' intent to constrain executive power even during wartime:[17]

[t]hat military powers of the Commander in Chief were not to supersede representative government of internal affairs seems obvious from the Constitution and from elementary American history. Time out of mind, and even now in many parts of the world, a military commander can seize private housing to shelter his troops. Not so, however, in the United States, for the Third Amendment says ... [E]ven in war time, his seizure of needed military housing must be authorized by Congress.[19]

One of the few times a federal court was asked to invalidate a law or action on Third Amendment grounds was in Engblom v. Carey (1982).[20] In 1979, prison officials in New York organized a strike; they were evicted from their prison facility residences, which were reassigned to members of the National Guard who had temporarily taken their place as prison guards. The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit ruled: (1) that the term owner in the Third Amendment includes tenants (paralleling similar cases regarding the Fourth Amendment, governing search and seizure), (2) National Guard troops are "soldiers" for purposes of the Third Amendment, and (3) that the Third Amendment is incorporated (applies to the states) by virtue of the Fourteenth Amendment.[21] The case was remanded to the district court, which dismissed it on the grounds that state officials could not have been aware of this interpretation.[22]

In the most recent Third Amendment decision handed down by a federal court, on February 2, 2015, the United States District Court for the District of Nevada held in Mitchell v. City of Henderson that the Third Amendment does not apply to intrusions by municipal police officers as, despite their appearance and equipment, they are not soldiers.[23]

In an earlier case, United States v. Valenzuela (1951),[24] the defendant asked that a federal rent-control law be struck down because it was "the incubator and hatchery of swarms of bureaucrats to be quartered as storm troopers upon the people in violation of Amendment III of the United States Constitution."[25] The court declined his request. Later, in Jones v. United States Secretary of Defense (1972),[26] Army reservists unsuccessfully cited the Third Amendment as justification for refusing to march in a parade. Similar arguments in a variety of contexts have been denied in other cases.[27]

Appearance in culture

As the Third Amendment has had little occasion to be invoked, it has been used for comedic purposes, such as

- The Onion, "Third Amendment Rights Group Celebrates Another Successful Year" (Oct. 5, 2007)[28]

- In the webcomic xkcd, where "Black Hat" pleads the third when accused of stealing a nuclear submarine. (Oct. 29, 2008)[29]

- Duffel Blog, "SPONSORED: Veteran Company Debuts Line Of Pro-3rd Amendment T-Shirts" (Jan., 2015),[30] which satirizes veteran-owned apparel companies such as Ranger Up.

- Third Amendment Lawyers Association (ÞALA)[31]

- John Mulaney, Saturday Night Live, Monologue (Feb. 29, 2020)[32]

References

- Notes

- All three states would later ratify the Bill of Rights for sesquicentennial celebrations in 1939.[12]

- Citations

- "How Did America's Police Become a Military Force On the Streets?". American Bar Association. 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- "The Third Amendment". Revolutionary War and Beyond. September 7, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- Mahoney, Dennis J. (1986). "Third Amendment". Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- "Third Amendment". U*X*L Encyclopedia of U.S. History. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . January 1, 2009. Archived from the original on November 6, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- "Bill of Rights (1791)". PBS. December 2006.

- "Parliament passes the Quartering Act". HISTORY.com.

- Alderman and Kennedy, pp. 107–108

- Beeman, pp. 341–43

- Bell, pp. 135–36

- "Bill of Rights". National Archives. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- Wood, p. 71

- Levy, Leonard W. (1986). "Bill of Rights (United States)". Encyclopedia of the American Constitution. – via HighBeam Research (subscription required) . Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- Labunski, p. 245

- Labunski, p. 255

- Bell, p. 140

- "Third Amendment". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- Amar, p. 62

- 381 U.S. 479, 484 (1965)

- Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579, 644 (1952)

- 677 F.2d 957 (2d. Cir. 1982)

- Bell, p. 143

- Young, Stephen E. (2003). The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878: A Documentary History. Wm. S. Hein Publishing. p. CRS-14 (fn29). ISBN 978-0-8377-3900-7. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- Mitchell v. City of Henderson, No. 2:13–cv–01154–APG–CWH, 2015 WL 427835 (D. Nev. February 2, 2015)

- 95 F. Supp. 363 (S.D. Cal. 1951)

- Bell, p. 142

- 346 F. Supp. 97 (D. Minn. 1972)

- Bell, pp. 141–42

- "Third Amendment Rights Group Celebrates Another Successful Year". The Onion. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Munroe, Randall. "Secretary: Part 3". xkcd. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- "SPONSORED: Veteran Company Debuts Line Of Pro-3rd Amendment T-Shirts". Duffel Blog. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- "THIRD AMENDMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION (ÞALA)". THIRD AMENDMENT LAWYERS ASSOCIATION (ÞALA). Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Itzkoff, Dave (March 1, 2020). "On 'S.N.L.', John Mulaney and Jake Gyllenhaal Find Humor in the Coronavirus". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Bibliography

- Alderman, Ellen and Caroline Kennedy (1991). In Our Defense. Avon.

- Amar, Akhil Reed (1998). The Bill of Rights. Yale University Press.

- Beeman, Richard (2009). Plain, Honest Men: The Making of the American Constitution. Random House.

- Bell, Tom W. (1993) "The Third Amendment: Forgotten but Not Gone". William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal 2.1: pp. 117–150.

- Labunski, Richard E. (2006). James Madison and the struggle for the Bill of Rights. Oxford University Press.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789–1815. Oxford University Press.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |